Tuberculosis historical perspective

|

Tuberculosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Tuberculosis historical perspective On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Tuberculosis historical perspective |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Tuberculosis historical perspective |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Tuberculosis has been present in humans since antiquity. The earliest unambiguous detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is in the remains of bison dated 18,000 years before the present.[1] However, whether tuberculosis originated in cattle and then transferred to humans, or diverged from a common ancestor, is currently unclear.[2]

Historical Perspective

Skeletal remains show prehistoric humans (4000 BC) had TB, and tubercular decay has been found in the spines of mummies from 3000-2400 BC.[3] Phthisis is a Greek term for tuberculosis; around 460 BC, Hippocrates identified phthisis as the most widespread disease of the times involving coughing up blood and fever, which was almost always fatal.[4] Genetic studies suggest that TB was present in South America for about 2,000 years.[5] In South America, the earliest evidence of tuberculosis is associated with the Paracas-Caverna culture (circa 750 BC to circa 100 AD).[6]

In the past, tuberculosis was called consumption, because it seemed to consume people from within, with a bloody cough, fever, pallor, and long relentless wasting. Other names included phthisis (Greek for consumption) and phthisis pulmonalis; scrofula (in adults), affecting the lymphatic system and resulting in swollen neck glands; tabes mesenterica, TB of the abdomen and lupus vulgaris, TB of the skin; wasting disease; white plague, because sufferers appear markedly pale; king's evil, because it was believed that a king's touch would heal scrofula; and Pott's disease, or gibbus of the spine and joints.[7][8] Miliary tuberculosis – now commonly known as disseminated TB– occurs when the infection invades the circulatory system resulting in lesions which have the appearance of millet seeds on x-ray.[7][9]

Folklore

Before the Industrial Revolution, tuberculosis may sometimes have been regarded as vampirism. When one member of a family died from it, the other members that were infected would lose their health slowly. People believed that this was caused by the original victim draining the life from the other family members. Furthermore, people who had TB exhibited symptoms similar to what people considered to be vampire traits. People with TB often have symptoms such as red, swollen eyes (which also creates a sensitivity to bright light), pale skin and coughing blood, suggesting the idea that the only way for the afflicted to replenish this loss of blood was by sucking blood.[10] Another folk belief attributed it to being forced, nightly, to attend fairy revels, so that the victim wasted away owing to lack of rest; this belief was most common when a strong connection was seen between the fairies and the dead.[11] Similarly, but less commonly, it was attributed to the victims being 'hagridden'—being transformed into horses by witches (hags) to travel to their nightly meetings, again resulting in a lack of rest.[11]

TB was romanticized in the nineteenth century. Many at the time believed TB produced feelings of euphoria referred to as 'Spes phthisica' or 'hope of the consumptive'. It was believed that TB sufferers who were artists had bursts of creativity as the disease progressed. It was also believed that TB sufferers acquired a final burst of energy just before they died which made women more beautiful and men more creative.[12]

Study and Treatment

The study of tuberculosis dates back to The Canon of Medicine written by Ibn Sina (Avicenna) in the 1020s. He was the first physician to identify pulmonary tuberculosis as a contagious disease and suggest that it could spread through contact with soil and water.[13][14] He developed the method of quarantine in order to limit the spread of tuberculosis.[15]

Although it was established that the pulmonary form was associated with 'tubercles' by Dr Richard Morton in 1689,[16][17] due to the variety of its symptoms, TB was not identified as a single disease until the 1820s and was not named 'tuberculosis' until 1839 by J. L. Schönlein.[18] During the years 1838–1845, Dr. John Croghan, the owner of Mammoth Cave, brought a number of tuberculosis sufferers into the cave in the hope of curing the disease with the constant temperature and purity of the cave air: they died within a year.[19] The first TB sanatorium opened in 1859 in Görbersdorf, Germany (today Sokołowsko, Poland) by Hermann Brehmer.[20]

In regard to this claim, The Times for January 15, 1859, page 5, column 5, carries an advertisement seeking funds for the Bournemouth Sanatorium for Consumption, referring to the balance sheet for the past year, and offering an annual report to prospective donors, implying that this sanatorium was in existence at least in 1858.

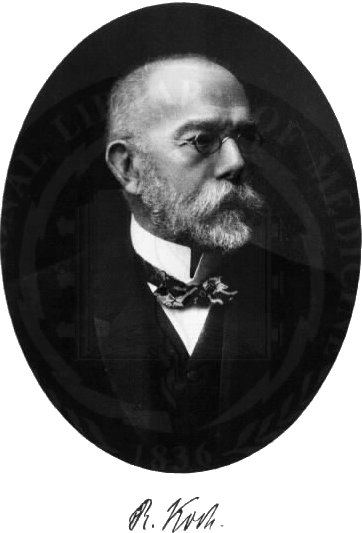

The bacillus causing tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, was identified and described on March 24, 1882 by Robert Koch. He received the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1905 for this discovery.[21] Koch did not believe that bovine (cattle) and human tuberculosis were similar, which delayed the recognition of infected milk as a source of infection. Later, this source was eliminated by the pasteurization process. Koch announced a glycerine extract of the tubercle bacilli as a remedy for tuberculosis in 1890, calling it 'tuberculin'. It was not effective, but was later adapted as a test for pre-symptomatic tuberculosis.[22]

The first genuine success in immunizing against tuberculosis was developed from attenuated bovine-strain tuberculosis by Albert Calmette and Camille Guerin in 1906. It was called 'BCG' (Bacillus of Calmette and Guerin). The BCG vaccine was first used on humans in 1921 in France, but it wasn't until after World War II that BCG received widespread acceptance in the USA, Great Britain, and Germany.

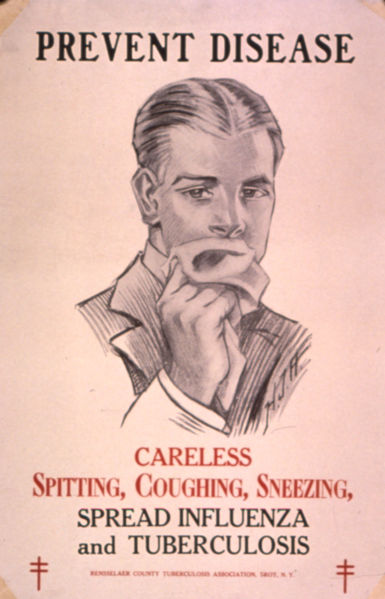

Tuberculosis, or 'consumption' as it was commonly known, caused the most widespread public concern in the 19th and early 20th centuries as an endemic disease of the urban poor. In 1815, one in four deaths in England was of consumption; by 1918 one in six deaths in France were still caused by TB. In the 20th century, tuberculosis killed an estimated 100 million people.[23] After the establishment in the 1880s that the disease was contagious, TB was made a notifiable disease in Britain; there were campaigns to stop spitting in public places, and the infected poor were encouraged to enter sanatoria that resembled prisons; the sanatoria for the middle and upper classes offered excellent care and constant medical attention.[20] Whatever the purported benefits of the fresh air and labor in the sanatoria, even under the best conditions, 50% of those who entered were dead within five years (1916).[20]

The promotion of Christmas Seals began in Denmark during 1904 as a way to raise money for tuberculosis programs. It expanded to the United States and Canada in 1907–08 to help the National Tuberculosis Association (later called the American Lung Association).

In the United States, concern about the spread of tuberculosis played a role in the movement to prohibit public spitting except into spittoons.

In Europe, deaths from TB fell from 500 out of 100,000 in 1850 to 50 out of 100,000 by 1950. Improvements in public health were reducing tuberculosis even before the arrival of antibiotics, although the disease remained a significant threat to public health, such that when the Medical Research Council was formed in Britain in 1913 its initial focus was tuberculosis research.[24]

It was not until 1946 with the development of the antibiotic streptomycin that effective treatment and cure became possible. Prior to the introduction of this drug, the only treatment besides sanatoria were surgical interventions, including the pneumothorax technique—collapsing an infected lung to rest it and allow lesions to heal—a technique that was of little benefit and was largely discontinued by the 1950s.[25] The emergence of multidrug-resistant TB has again introduced surgery as part of the treatment for these infections. Here, surgical removal of chest cavities will reduce the number of bacteria in the lungs, as well as increasing the exposure of the remaining bacteria to drugs in the bloodstream, and is therefore thought to increase the effectiveness of the chemotherapy.[26]

Hopes that the disease could be completely eliminated have been dashed since the rise of drug-resistant strains in the 1980s. For example, tuberculosis cases in Britain, numbering around 117,000 in 1913, had fallen to around 5,000 in 1987, but cases rose again, reaching 6,300 in 2000 and 7,600 cases in 2005.[27] Due to the elimination of public health facilities in New York and the emergence of HIV, there was a resurgence in the late 1980s.[28] The number of those failing to complete their course of drugs is high. NY had to cope with more than 20,000 unnecessary TB-patients with multidrug-resistant strains (resistant to, at least, both Rifampin and Isoniazid). The resurgence of tuberculosis resulted in the declaration of a global health emergency by the World Health Organization in 1993.[29]

References

- ↑ Rothschild B, Martin L, Lev G, Bercovier H, Bar-Gal G, Greenblatt C, Donoghue H, Spigelman M, Brittain D (2001). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA from an extinct bison dated 17,000 years before the present". Clin Infect Dis. 33 (3): 305–11. PMID 11438894.

- ↑ Pearce-Duvet J (2006). "The origin of human pathogens: evaluating the role of agriculture and domestic animals in the evolution of human disease". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 81 (3): 369–82. PMID 16672105.

- ↑ Zink A, Sola C, Reischl U, Grabner W, Rastogi N, Wolf H, Nerlich A (2003). "Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNAs from Egyptian mummies by spoligotyping". J Clin Microbiol. 41 (1): 359–67. PMID 12517873.

- ↑ Hippocrates. Aphorisms. Accessed 07 October 2006.

- ↑ Konomi N, Lebwohl E, Mowbray K, Tattersall I, Zhang D (2002). "Detection of mycobacterial DNA in Andean mummies". J Clin Microbiol. 40 (12): 4738–40. PMID 12454182.

- ↑ "South America: Prehistoric Findings". Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Vol. 98 (Suppl.I) January 2003. Retrieved on 2007-02-08.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Tuberculosis Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed.

- ↑ Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms English Glossary of Archaic Medical Terms, Diseases and Causes of Death. Accessed 09 Oct 06

- ↑ Disseminated tuberculosis NIH Medical Encyclopedia. Accessed 09 Oct 06

- ↑ Sledzik P, Bellantoni N (1994). "Brief communication: bioarcheological and biocultural evidence for the New England vampire folk belief". Am J Phys Anthropol. 94 (2): 269–74. PMID 8085617.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies "Consumption" (Pantheon Books, 1976) p. 80. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ↑ Lawlor, Clark. "Transatlantic Consumptions: Disease, Fame and Literary Nationalism in the Davidson Sisters, Southey, and Poe". Studies in the Literary Imagination, Fall 2003. Available at findarticles.com. Retrieved on 2007-06-08.

- ↑ Y. A. Al-Sharrah (2003), "The Arab Tradition of Medical Education and its Relationship with the European Tradition", Prospects 33 (4), Springer.

- ↑ George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science.

(cf. Dr. A. Zahoor and Dr. Z. Haq (1997). Quotations From Famous Historians of Science, Cyberistan.) - ↑ David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD (August 2003). "Arab Roots of European Medicine", Heart Views 4 (2).

- ↑ Who Named It? Léon Charles Albert Calmette. Retrieved on 6 October 2006.

- ↑ Trail R (1970). "Richard Morton (1637–1698)". Med Hist. 14 (2): 166–74. PMID 4914685.

- ↑ Zur Pathogenie der Impetigines. Auszug aus einer brieflichen Mitteilung an den Herausgeber. [Müller’s] Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin. 1839, page 82.

- ↑ Kentucky: Mammoth Cave long on history. CNN. 27 February 2004. Accessed 08 October 2006.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 McCarthy OR (2001). "The key to the sanatoria". J R Soc Med. 94 (8): 413–7. PMID 11461990.

- ↑ Nobel Foundation. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1905. Accessed 07 October 2006.

- ↑ Waddington K (2004). "To stamp out "so terrible a malady": bovine tuberculosis and tuberculin testing in Britain, 1890–1939". Med Hist. 48 (1): 29–48. PMID 14968644.

- ↑ Torrey EF and Yolken RH. 2005. Their bugs are worse than their bite. Washington Post, April 3, p. B01.

- ↑ [[Medical Research Council (UK)|]]. MRC's contribution to Tuberculosis research. Accessed 02 July 2007.

- ↑ Wolfart W (1990). "[Surgical treatment of tuberculosis and its modifications—collapse therapy and resection treatment and their present-day sequelae]". Offentl Gesundheitswes. 52 (8–9): 506–11. PMID 2146567.

- ↑ Lalloo U, Naidoo R, Ambaram A (2006). "Recent advances in the medical and surgical treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis". Curr Opin Pulm Med. 12 (3): 179–85. PMID 16582672.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis – Respiratory and Non-respiratory Notifications, England and Wales, 1913-2005". Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections. 21 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Paolo W, Nosanchuk J (2004). "Tuberculosis in New York city: recent lessons and a look ahead". Lancet Infect Dis. 4 (5): 287–93. PMID 15120345.

- ↑ World Health Organization (WHO). Frequently asked questions about TB and HIV. Retrieved 6 October 2006.