Rabies epidemiology and demographics

|

Rabies Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Rabies epidemiology and demographics On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Rabies epidemiology and demographics |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Rabies epidemiology and demographics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Epidemiology and Demographics

The epidemiology of rabies addresses several questions: what animals have rabies and in what regions of the country, how many people get rabies and from what animals, and what are the best strategies for preventing rabies in people and animals. Epidemiologic information is often presented as statistical data (e.g., numbers or percentages in graphs and on maps). For example, in 2001, 7,437 cases of rabies were reported in the United States. Raccoons accounted for almost 40% of reported cases.

Rabies worldwide

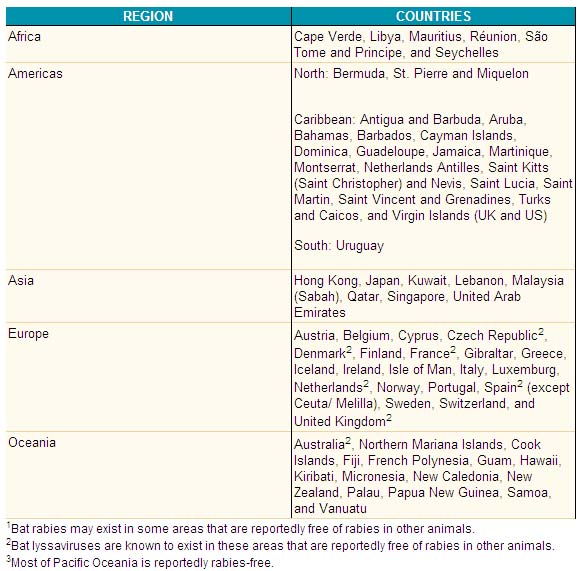

Rabies is found on all continents except Antarctica. In certain areas of the world, canine rabies remains highly endemic, including (but not limited to) parts of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America (8,9). Table 4-14 lists countries that have reported no cases of rabies during the most recent period for which information is available (formerly referred to as “rabies-free countries”).

More than 99% of all human deaths from rabies occur in Africa, Asia, South America and India which report thirty thousand deaths annually.[1] One of the sources of recent flourishing of rabies in the East Asia is the pet boom. China introduced the "One-dog policy" in November 2006 to control the problem.[2]

The English Channel, dog licensing, killing of stray dogs, muzzling and other measures contributed to the eradication of rabies from the United Kingdom in the early 20th century. More recently, large-scale vaccination of cats, dogs and ferrets has been successful in combatting rabies in some developed countries.

The rabies virus survives in wide-spread, varied, rural fauna reservoirs. However, in Asia, parts of Latin America and large parts of Africa, dogs remain the principal host. Mandatory vaccination of animals is less effective in rural areas. Especially in developing countries, pets may not be privately kept and their destruction may be unacceptable. Oral vaccines can be safely distributed in baits, and this has successfully reduced rabies in rural areas of France, Ontario, Texas, Florida and elsewhere. Vaccination campaigns may be expensive, and a cost-benefit analysis can lead those responsible to opt for policies of containment rather than elimination of the disease.

Many territories, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Taiwan, Japan, Hawaii, Mauritius, Barbados and Guam, are free of rabies, although there may be a very low prevalence of rabies among bats in the UK; see below.

New Zealand and Australia have never had rabies.[2] However, in Australia, the Australian Bat Lyssavirus occurs normally in both insectivorous and fruit eating bats (flying foxes) from most mainland states. Scientists believe it is present in bat populations throughout the range of flying foxes in Australia.

Additional information can be obtained from the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/rabies/rabnet/en/), the Pan American Health Organization (http://www.paho.org/english/ad/dpc/vp/rabia.htm), the Rabies Bulletin-Europe (http://www.rbe.fli.bund.de), the World Organization for Animal Health (http://www.oie.int/eng/en_index.htm), local health authorities of the country, the embassy, or the local consulate’s office in the United States. Lists are provided only as a guide, because up to date information may not be available, surveillance standards vary, and reporting status can change suddenly as a result of disease re-introduction or emergence.

Countries and political units reporting no indigenous cases of rabies during 2005:

Rabies in the United States

Rabies was once rare in the United States outside the Southern states, but raccoons in the mid-Atlantic and northeast United States have been suffering from a rabies epidemic since the 1970s, which is now moving westwards into Ohio.[3]

The particular variant of the virus has been identified in the southeastern United States raccoon population since the 1950s, and is believed to have traveled to the northeast as the result of infected raccoons being among those caught and transported from the southeast to the northeast by human hunters attempting to replenish the declining northeast raccoon population.[4] As a result, urban residents of these areas have become more wary of the large but normally unseen urban raccoon population. It has become the common assumption that any raccoon seen diurnally is infected; certainly the reported behavior of most such animals appears to show some sort of illness, and necropsies can confirm rabies. Whether as a result of increased vigilance or only the common human avoidance reaction to any other animal not normally seen, such as a raccoon, there has only been one documented human rabies case as a result of this variant.[5] This does not include, however, the greatly increasing rate of prophylactic rabies treatments in cases of possible exposure, which numbered fewer than one hundred humans annually in the state of New York before 1990, for instance, but rose to approximately ten thousand annually between 1990 and 1995. At approximately $1,500 per course of treatment, this represents a considerable public health expenditure. Raccoons do constitute approximately 50% of the approximately eight thousand documented non-human rabies cases in the United States.[6] Domestic animals constitute only 8% of rabies cases, but are increasing at a rapid rate.[6]

In the midwestern United States, skunks are the primary carriers of rabies, composing one hundred and thirty-four of the two hundred and thirty-seven documented non-human cases in 1996. The most widely distributed reservoir of rabies in the United States, however, and the source of most human cases in the U.S., are bats. Nineteen of the twenty-two human rabies cases documented in the United States between 1980 and 1997 have been identified genetically as bat rabies. In many cases, victims are not even aware of having been bitten by a bat, assuming that a small puncture wound found after the fact was the bite of an insect or spider; in some cases, no wound at all can be found, leading to the hypothesis that in some cases the virus can be contracted via inhaling airborne aerosols from the vicinity of bats. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned on May 9, 1997, that a woman who died in October, 1996 in Cumberland County, Kentucky and a man who died in December, 1996 in Missoula County, Montana were both infected with a rabies strain found in silver-haired bats; although bats were found living in the chimney of the woman's home and near the man's place of employment, neither victim could remember having had any contact with them. This inability to recognize a potential infection, in contrast to a bite from a dog or raccoon, leads to a lack of proper prophylactic treatment, and is the cause of the high mortality rate for bat bites.

Rabies Prevalence in the United States

In this century, the number of human deaths in the United States attributed to rabies has declined from 100 or more each year to an average of 1 or 2 each year. Two programs have been responsible for this decline. First, animal control and vaccination programs begun in the 1940's have practically eliminated domestic dogs as reservoirs of rabies in the United States. Second, effective human rabies vaccines and immunolglobins have been developed . All human cases in the United States since 1990 are summarized in the Table of Human Rabies Cases from 1990- 2001.

- Virginia -1998

- California - 2000

- New York - 2000

- Georgia - 2000

- Minnesota - 2000

- Wisconsin - 2000

- California - 2001

- California - 2002

- Tennessee - 2002

- Iowa - 2002

- Virginia - 2003

United States Rabies Surveillance Data, 2001

Each year, scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collect information about cases of animal and human rabies from the state health departments and publish the information in a summary report. The most recent report, entitled "Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2001," contains the epidemiologic information on rabies during 2001. This report can be found in its entirety in Publications. Below is a brief summary of the surveillance information for 2000, including maps showing the distribution of rabies in the United States.

In 2001, 49 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico reported 7,437 cases of rabies in animals and no cases in humans to CDC (Hawaii is the only state that has never reported an indigenously acquired rabies case in humans or animals). The total number of reported cases increased by 0.92% from those reported in 2000 (7,369 cases).

Wild Animals

Wild animals accounted for 93% of reported cases of rabies in 2001. Raccoons continued to be the most frequently reported rabid wildlife species (37.2% of all animal cases during 2001), followed by skunks (30.7%), bats (17.2%), foxes (5.9%), and other wild animals, including rodents and lagomorphs (0.7%). Reported cases in raccoons and foxes decreased 0.4% and 3.5% respectively from the totals reported in 2000. Reported cases in skunks, and bats increased 2.6%, and 3.3% respectively from the totals reported in 2000.

Outbreaks of rabies infections in terrestrial mammals like raccoons, skunks, foxes, and coyotes are found in broad geographic regions across the United States. Geographic boundaries of currently recognized reservoirs for rabies in terrestrial mammals are shown on the map below.

Domestic Animals

Domestic species accounted for 6.8% of all rabid animals reported in the United States in 2001. The number of reported rabid domestic animals decreased 2.4% from the 509 cases reported in 2000 to 497 in 2001.

In 2001, cases of rabies in cats increased 8.4%, whereas those in dogs, cattle, horses, sheep and goats, and swine decreased 21.9%, 1.2%, 1.9% and 70.0% respectively compared with those reported in 2000. Rabies cases in cats continue to be more than twice as numerous as those in dogs or cattle. Pennsylvania reported the largest number of rabid domestic animals (46) for any state, followed by New York (43).

Successful vaccination programs that began in the 1940s caused a decline in dog rabies in this country. But, as the number of cases of rabies in dogs decreased, rabies in wild animals increased, as shown in the graph below.

References

- ↑ "Rabies vaccine". WHO - Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ↑ The Toronto Star "China cracks down on rabid dog menace"

- ↑ "Compendium of animal rabies prevention and control, 2006". MMWR Recomm Rep. 55 (RR-5): 1–8. 2006.

- ↑ Nettles VF, Shaddock JH, Sikes RK, Reyes CR (1979). "Rabies in translocated raccoons". Am J Public Health. 69 (6): 601–2. PMID 443502.

- ↑ Dietzschold, B, Proniak, M (2003). "First Human Death Associated with Raccoon Rabies --- Virginia, 2003". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control. 52 (45): 1102–1103. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Krebs JW, Strine TW, Smith JS, Noah DL, Rupprecht CE, Childs JE (1996). "Rabies surveillance in the United States during 1995". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 209 (12): 2031–44. PMID 8960176.