Q fever: Difference between revisions

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==[[Q fever history and symptoms|History & Symptoms]]== | ==[[Q fever history and symptoms|History & Symptoms]]== | ||

== Diagnosis == | == Diagnosis == | ||

Revision as of 14:54, 2 February 2012

For patient information click here

| Q fever | |

| |

|---|---|

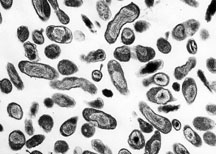

| Organism Responsible for Q fever, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH | |

| ICD-10 | A78 |

| ICD-9 | 083.0 |

| MeSH | D011778 |

|

Q fever Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Q fever On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Q fever |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Epidemiology & Demographics

Pathophysiology

History & Symptoms

Diagnosis

Because the signs and symptoms of Q fever are not specific to this disease, it is difficult to make an accurate diagnosis without appropriate laboratory testing. Results from some types of routine laboratory tests in the appropriate clinical and epidemiologic settings may suggest a diagnosis of Q fever. For example, a platelet count may be suggestive because persons with Q fever may show a transient thrombocytopenia. Confirming a diagnosis of Q fever requires serologic testing to detect the presence of antibodies to Coxiella burnetii antigens. In most laboratories, the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) is the most dependable and widely used method. Coxiella burnetii may also be identified in infected tissues by using immunohistochemical staining and DNA detection methods.

Coxiella burnetii exists in two antigenic phases called phase I and phase II. This antigenic difference is important in diagnosis. In acute cases of Q fever, the antibody level to phase II is usually higher than that to phase I, often by several orders of magnitude, and generally is first detected during the second week of illness. In chronic Q fever, the reverse situation is true. Antibodies to phase I antigens of C. burnetii generally require longer to appear and indicate continued exposure to the bacteria. Thus, high levels of antibody to phase I in later specimens in combination with constant or falling levels of phase II antibodies and other signs of inflammatory disease suggest chronic Q fever. Antibodies to phase I and II antigens have been known to persist for months or years after initial infection.

Recent studies have shown that greater accuracy in the diagnosis of Q fever can be achieved by looking at specific levels of classes of antibodies other than IgG, namely IgA and IgM. Combined detection of IgM and IgA in addition to IgG improves the specificity of the assays and provides better accuracy in diagnosis. IgM levels are helpful in the determination of a recent infection. In acute Q fever, patients will have IgG antibodies to phase II and IgM antibodies to phases I and II. Increased IgG and IgA antibodies to phase I are often indicative of Q fever endocarditis.

History and Symptoms

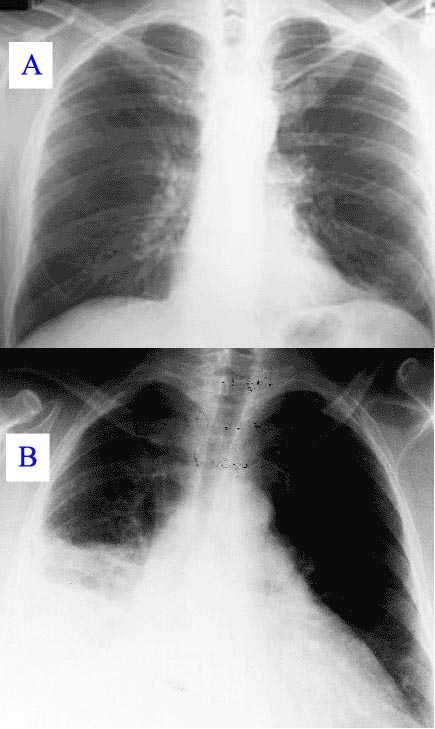

Only about one-half of all people infected with C. burnetii show signs of clinical illness. Most acute cases of Q fever begin with sudden onset of one or more of the following: high fevers (up to 104-105° F), severe headache, general malaise, myalgia, confusion, sore throat, chills, sweats, non-productive cough, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and chest pain. Fever usually lasts for 1 to 2 weeks. Weight loss can occur and persist for some time. Thirty to fifty percent of patients with a symptomatic infection will develop pneumonia. Additionally, a majority of patients have abnormal results on liver function tests and some will develop hepatitis. In general, most patients will recover to good health within several months without any treatment. Only 1%-2% of people with acute Q fever die of the disease.

Chronic Q fever, characterized by infection that persists for more than 6 months is uncommon but is a much more serious disease. Patients who have had acute Q fever may develop the chronic form as soon as 1 year or as long as 20 years after initial infectioQ-fever can cause endocarditis (infection of the heart valves) which may require transoesophageal echocardiography to diagnose. Most patients who develop chronic Q fever have pre-existing valvular heart disease or have a history of vascular graft. Transplant recipients, patients with cancer, and those with chronic kidney disease are also at risk of developing chronic Q fever. As many as 65% of persons with chronic Q fever may die of the disease. Q-fever hepatitis manifests as an elevation of ALT and AST, but a definitive diagnosis is only possible on liver biopsy which shows the characteristic fibrin ring granulomas.[1]

The incubation period for Q fever varies depending on the number of organisms that initially infect the patient. Infection with greater numbers of organisms will result in shorter incubation periods. Most patients become ill within 2-3 weeks after exposure. Those who recover fully from infection may possess lifelong immunity against re-infection.

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

Coxiella burnetii is a highly infectious agent that is rather resistant to heat and drying. It can become airborne and inhaled by humans. A single C. burnetii organism may cause disease in a susceptible person. This agent could be developed for use in biological warfare and is considered a potential terrorist threat.

Treatment

Acute Pharmacotherapies

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice for acute Q fever. Antibiotic treatment is most effective when initiated within the first 3 days of illness. A dose of 100 mg of doxycycline taken orally twice daily for 15-21 days is a frequently prescribed therapy. Quinolone antibiotics have demonstrated good in vitro activity against C. burnetii and may be considered by the physician. Therapy should be started again if the disease relapses.

Q fever in pregnancy is especially difficult to treat because doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are contraindicated in pregnancy. The preferred treatment is five weeks of co-trimoxazole.[2]

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

Chronic Q fever endocarditis is much more difficult to treat effectively and often requires the use of multiple drugs. Two different treatment protocols have been evaluated: 1) doxycycline in combination with quinolones for at least 4 years and 2) doxycycline in combination with hydroxychloroquine for 1.5 to 3 years. The second therapy leads to fewer relapses, but requires routine eye exams to detect accumulation of chloroquine. Surgery to remove damaged valves may be required for some cases of C. burnetii endocarditis.

Prevention

In the United States, Q fever outbreaks have resulted mainly from occupational exposure involving veterinarians, meat processing plant workers, sheep and dairy workers, livestock farmers, and researchers at facilities housing sheep. Prevention and control efforts should be directed primarily toward these groups and environments.

The following measures should be used in the prevention and control of Q fever:

- Educate the public on sources of infection.

- Appropriately dispose of placenta, birth products, fetal membranes, and aborted fetuses at facilities housing sheep and goats.

- Restrict access to barns and laboratories used in housing potentially infected animals.

- Use only pasteurized milk and milk products.

- Use appropriate procedures for bagging, autoclaving, and washing of laboratory clothing.

- Vaccinate (where possible) individuals engaged in research with pregnant sheep or live C. burnetii.

- Quarantine imported animals.

- Ensure that holding facilities for sheep should be located away from populated areas. Animals should be routinely tested for antibodies to C. burnetii, and measures should be implemented to prevent airflow to other occupied areas.

- Counsel persons at highest risk for developing chronic Q fever, especially persons with pre-existing cardiac valvular disease or individuals with vascular grafts.

A vaccine for Q fever has been developed and has successfully protected humans in occupational settings in Australia. However, this vaccine is not commercially available in the United States. Persons wishing to be vaccinated should first have a skin and blood test to determine a history of previous exposure. Individuals who have previously been exposed to C. burnetii should not receive the vaccine because severe reactions, localized to the area of the injected vaccine, may occur. After a single dose of vaccine, protective immunity lasts for many years and revaccination is not generally required. Annual screening is typically recommended.[2] A vaccine for use in animals has also been developed, but it is not available in the United States.

Q fever is effectively prevented by intradermal vaccination using a vaccine composed of killed Coxiella burnetii organisms. A skin and blood test, prior to vaccination must be undertaken in order to establish whether there is pre-existing immunity, as vaccination of immune subjects can result in a severe local reaction. In 2001, Australia introduced a national Q fever vaccination program for people working in "at risk" occupations.

Other

Because of its route of infection it can be used as biological warfare agent. See also bioterrorism.Q-fever is category "B" agent. It is highly contagious and very stable in aerosols in a wide range of temperatures. Just 1-2 particles are enough to infect an individual. Q-fever microorganisms may survive on surfaces up to 60 days (like sporulating bacteria) and C. burnetii is known to reproduce and grow well in chicken egg embryos reaching very high concentrations. Protection against disease is offered by Q-Vax, a whole cell inactivated vaccine developed by a leading Australian vaccine manufacturing company CSL. (http://www.csl.com.au/QFever.asp)

History

It was first described by Edward Holbrook Derrick in abattoir workers in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. The "Q" stands for “query” and was applied historically at a time when the causative agent was unknown.

In 1937 the bacterium was isolated by Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Mavis Freeman from one of Derrick’s patients for the first time and identified as Rickettsia-species. H.R. Cox and Davis isolated the pathogen from ticks in Montana, USA in 1938, called it Rickettsia diasporica, it was considered nonpathogenic until laboratory investigators were infected; it was officially named Coxiella burnetii the same year. It is a zoonotic disease and most common animal reservoirs are cattle, sheep and goats. Coxiella burnetii is no longer regarded as closely related to Rickettsiae.

Acknowledgements

List of contributors:

Pilar Almonacid

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/submenus/sub_q_fever.htm http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/qfever/index.htm http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/qfever.htm

- ↑ van de Veerdonk FL, Schneeberger PM. (2006). "Patient with fever and diarrea". Clin Infect Dis. 42: 1051&ndash, 2.

- ↑ Carcopino X, Raoult D, Bretelle F, Boubli L, Stein A (2007). "Managing Q fever during pregnancy: The benefits of long-term Cctrimoxazole therapy". Clin Infect Dis. 45: 548&ndash, 555.

Template:Bacterial diseases

cs:Q-horečka

de:Q-Fieber

hr:Q groznica

it:Febbre Q

he:קדחת Q

nl:Q-koorts

fi:Q-kuume