Mononucleosis pathophysiology

|

Mononucleosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Mononucleosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Mononucleosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Mononucleosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Lakshmi Gopalakrishnan, M.B.B.S. [2]

Overview

Epstein-Barr virus, frequently referred to as EBV, is a member of the herpesvirus family and one of the most common human viruses. Transmission of the EBV through the air or blood does not normally occur. The incubation period, or the time from infection to appearance of symptoms, ranges from 4 to 6 weeks. Persons with infectious mononucleosis may be able to spread the infection to others for a period of weeks. However, no special precautions or isolation procedures are recommended, since the virus is also found frequently in the saliva of healthy people. In fact, many healthy people can carry and spread the virus intermittently for life. These people are usually the primary reservoir for person-to-person transmission. For this reason, transmission of the virus is almost impossible to prevent.

Transmission

- Transmission of EBV requires intimate contact with the saliva of an infected person.

- Saliva

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) shed for up to 18 months after primary infection

- Intermittent viral shedding thereafter in asymptomatic sero-positive patients

- Increased viral shedding in immunocompromised patients

- Blood transfusion (rare)

- Individuals in close living arrangements nearly always pass the infection onto each other, although symptoms may not present for months or even years.

Pathophysiology

- Following intimate contact with infected saliva, the virus infects B cells located in the oropharyngeal epithelium and subsequently spreads to involve the lymph nodes, liver and spleen.

- Humoral response: As with many viral infections, such as chicken pox, antibodies to the viral antigens are developed with resultant recovery from acute illness.

- In addition, these antibodies remain in the system for most individuals, creating a lifelong immunity to further infections.[1]

- Also, assessment of these specific antibodies forms the basis to diagnose mononucleosis in patients with atypical presentation or in heterophile negative cases.

- Cellular response:

- Is required to control the proliferation of infected B cells.

- This in turn, helps to terminate active EBV infection and also suppress future infections with EBV.

- Ineffective cellular response results in excessive proliferation of B cells with resultant EBV-associated malignancies such as Burkitt's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Pathophysiology based on clinical presentation

Intial Prodrome

Following the invasion of B cells by EBV there is a resultant acute elevation of cytokines which forms the background for the initial manifestation of disease which lasts for a week or two.

Recovery

- Usually, the longer the infected person remains symptomatic, the more the infection weakens the person's immune system, and hence the longer time is required to recover.

Dormant infection

- After an initial prodrome, the fatigue of mononucleosis often lasts from 1-2 months.

- The virus can remain dormant in the B cells indefinitely after symptoms have disappeared, and resurface at a later date.

- Many people exposed to the virus do not show symptoms of the disease, but remain carriers of the disease. This is especially true in children, in whom infection seldom causes more than a very mild cold which often goes undiagnosed.

- This dormant feature combined with long (4 to 6 week) incubation period of the disease, makes epidemiological control of the disease impractical.

Reactivation

- Approximately 6% of patients with prior infection have reported relapse.

- Cyclical reactivation of the virus, although rare in healthy people, is often a sign of immunological abnormalities in the small subset of organic disease patients in which the virus is active or reactivated.

- In case of a weak immune system, there is a possibility of EBV reactivation; consistent with the evidence of immune activation observed in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Chronic infection

- The course of the disease can also be chronic with symptoms lasting for months or years. This variant of mononucleosis has been referred to as chronic EBV syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome.

- Although the most recent medical studies have discounted the link between chronic EBV infection and chronic fatigue syndrome, some patients anecdotally report that chronic fatigue lasting for years after mononucleosis is part of a CFS.

- This confusion seems to lie in the nature of the link (note: any association does not prove or disprove causality) and possible misapprehension as to the syndromic nature of CFS. Also, some of this confusion may be attributed to the use of a new, broadened revision of the CFS research criteria, which has been criticised as overly inclusive.

- However, current studies suggest that there is an association between infectious mononucleosis and CFS [2]. Additionally, chronic fatigue states appear to occur in 10% of those who contract mononucleosis.[3]

- While chronic fatigue may rather be a common side effect of infectious mononucleosis, it should be noted that CFS is more than chronic fatigue, requiring at least four other symptoms, and a number of findings have been published which are not typical of EBV infection, although some complications may be shared. Additionally some CFS patients do not even describe fatigue as their worst problem.

- Majority of chronic post-infectious fatigue states appear not to be caused by a chronic viral infection, but be triggered by the acute infection.

- Direct and indirect evidence of persistent viral infection has been found in CFS, for example in muscle and via detection of an unusually low molecular weight RNase L enzyme, although the commonality and significance of such findings is disputed.

- Hickie et al, contend that mononucleosis appears to cause a hit and run injury to the brain in the early stages of the acute phase, thereby causing the chronic fatigue state. This would explain why in mononucleosis, fatigue very often lingers for months after the Epstein Barr Virus has been controlled by the immune system.

- However, it has also been noted in several (although altogether rare) cases that the only "symptom" displayed by a mononucleosis sufferer is elevated moods and higher energy levels, virtually the opposite of CFS and comparable to hypomania.

- Just how infectious mononucleosis changes the brain and causes fatigue (or lack thereof) in certain individuals remains to be seen. Such a mechanism may include activation of microglia in the brain of some individuals during the acute infection, thereby causing a slowly dissipating fatigue.

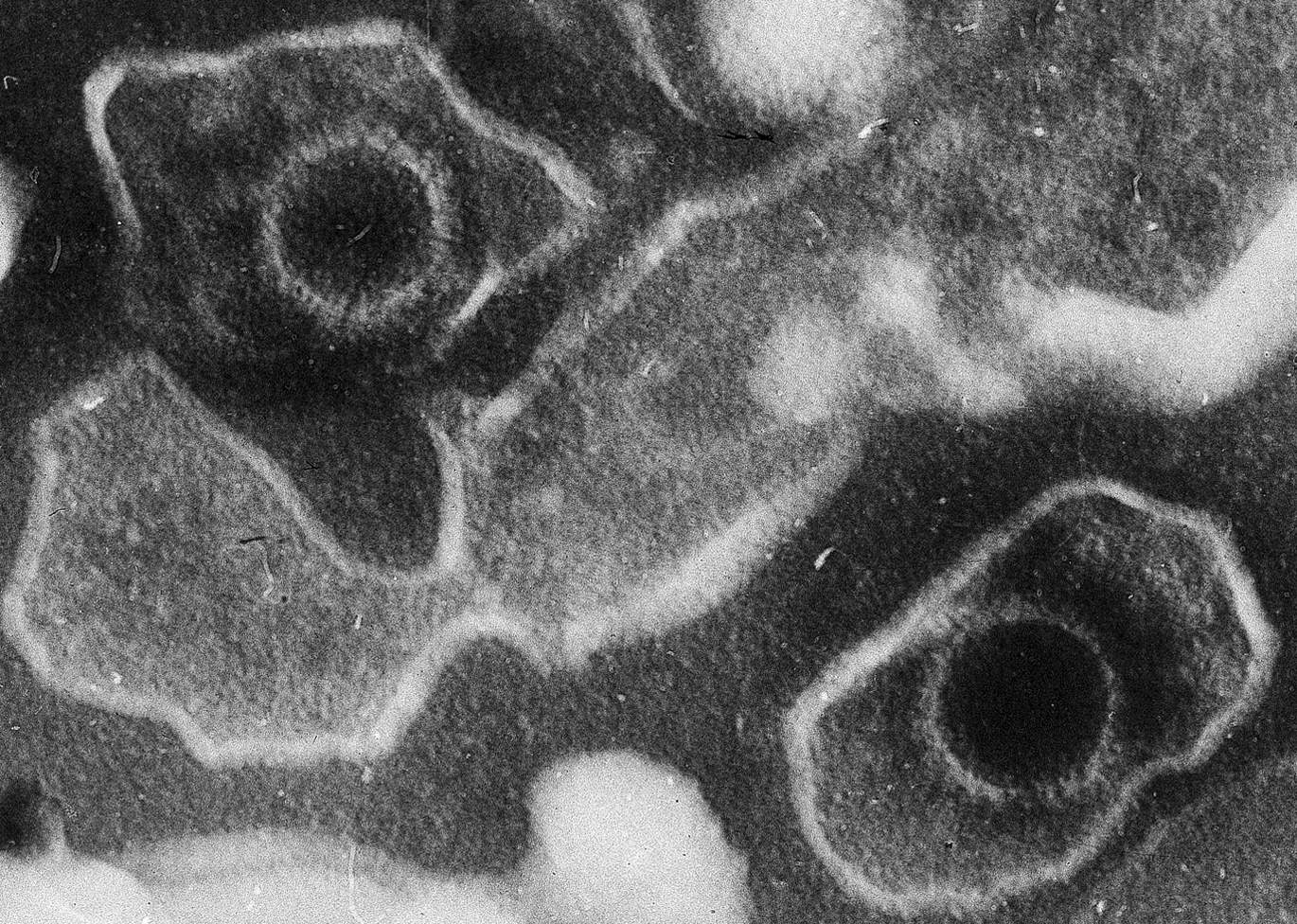

Electron microscopy

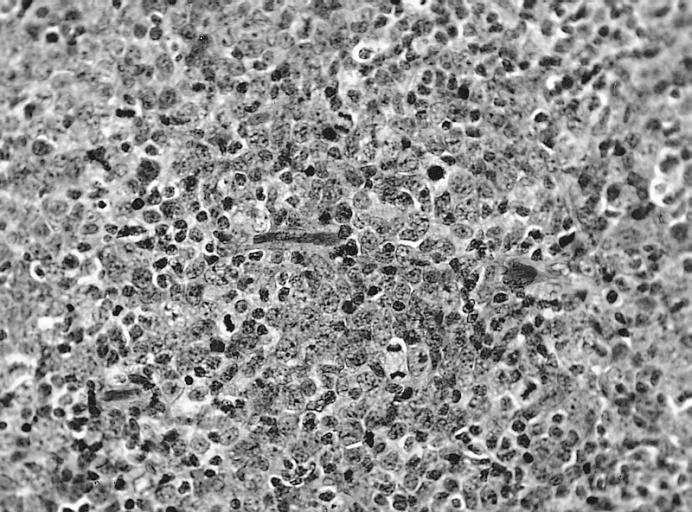

Microscopic pathology

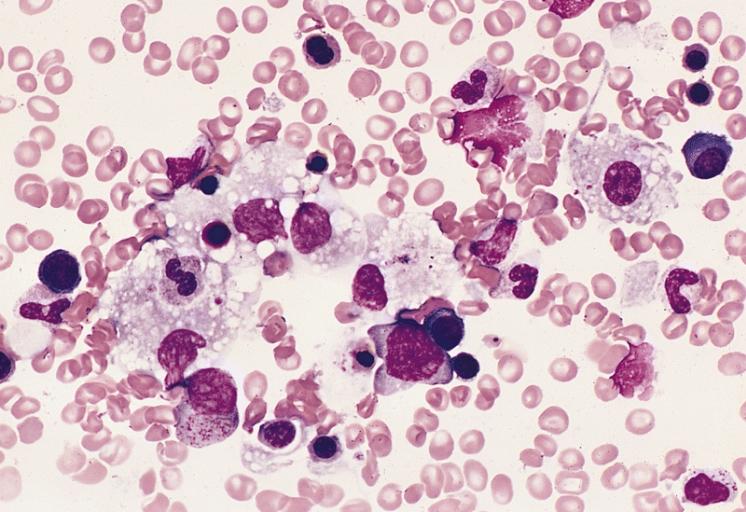

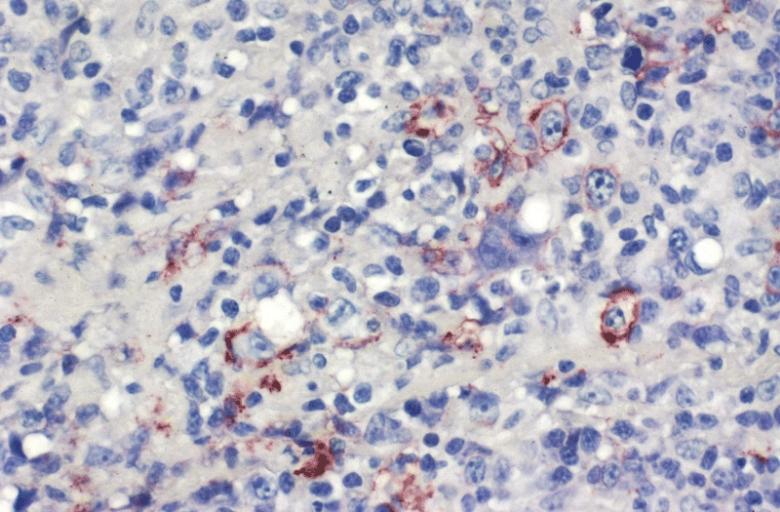

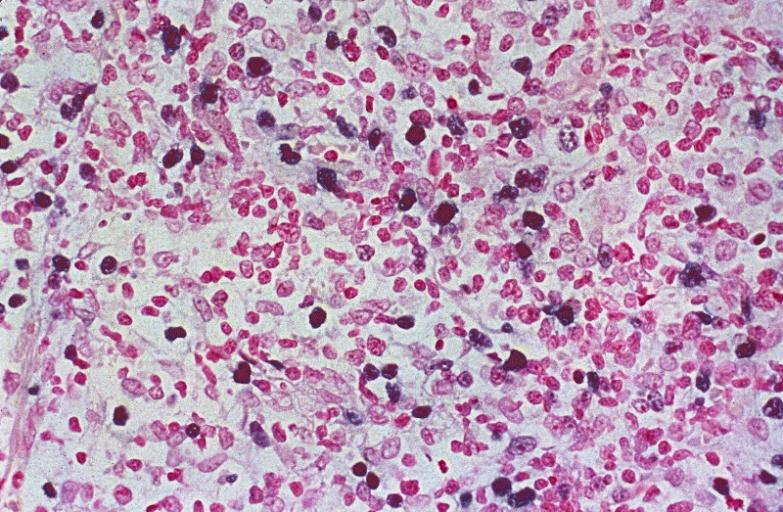

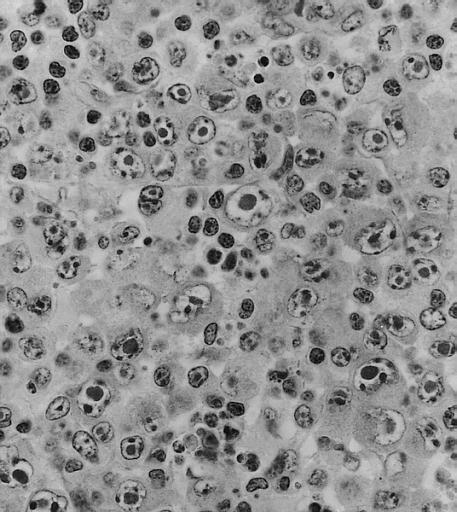

Images shown below are courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission. © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology

-

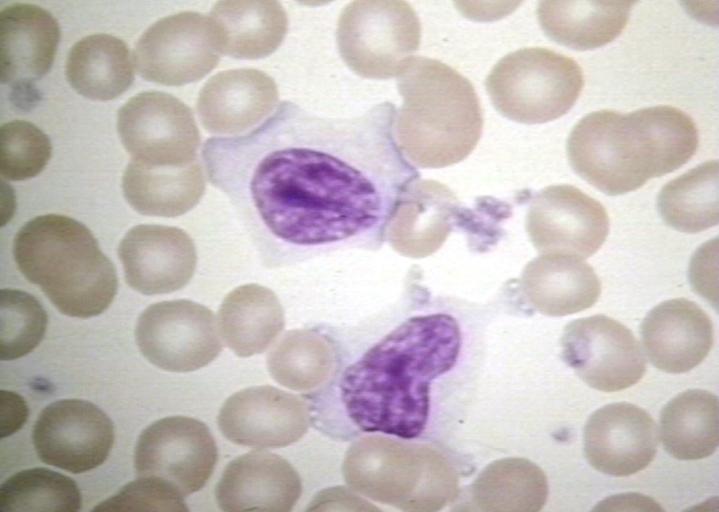

BONE MARROW: INFECTION-ASSOCIATED HEMOPHAGOCYTIC SYNDROME A bone marrow aspirate smear from a child with infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome secondary to an Epstein-Barr virus infection. On this field there are several large histiocytes. Phagocytosis of nucleated red blood cells, neutrophils, and platelets is evident. The histiocytes have the appearance of reactive cells and should be readily distinguishable from neoplastic histiocytes. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

-

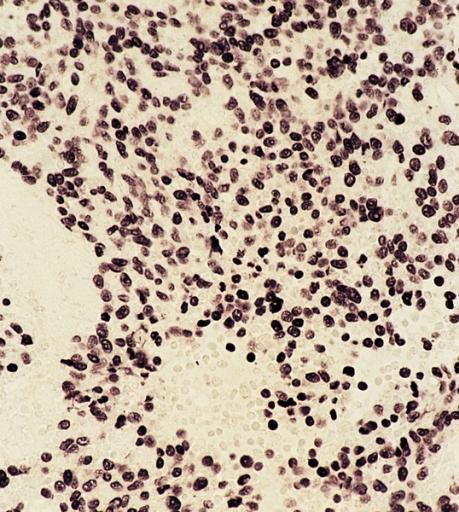

LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT: (Supplement) AIL/LYG CD20 staining (for B cells) in the viable tissue shows positive staining of scattered large lymphoid cells (C) which were also the cells that were positive for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization

-

LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT: (Supplement) AIL/LYG CD20 staining (for B cells) in the viable tissue shows positive staining of scattered large lymphoid cells (C) which were also the cells that were positive for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization

-

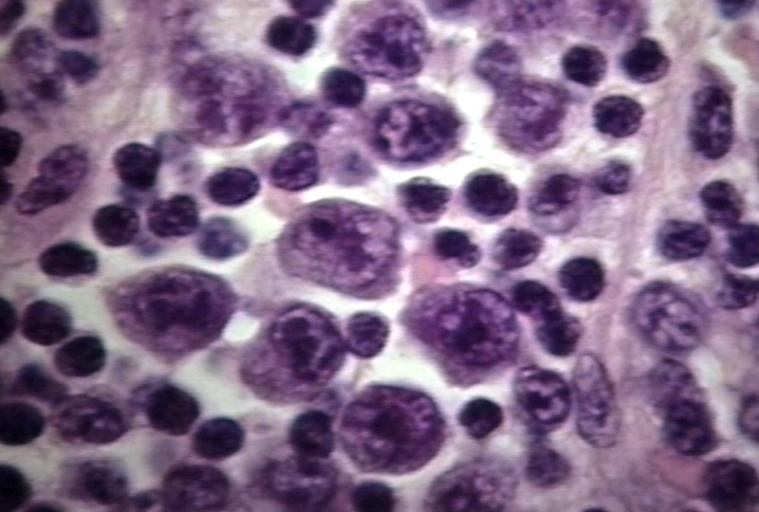

LYMPH NODES-SPLEEN: EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS-ASSOCIATED INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS A heterogeneous population is present, including cells mimicking Hodgkin cells. However, the spectrum of cell types and the extensive apoptosis present would not be found in Hodgkin's disease.

-

LYMPH NODES-SPLEEN: METASTATIC NASOPHARYNGEAL CARCINOMA IN LYMPH NODE PRESENTING AS METASTATIC CARCINOMA OF UNKNOWN PRIMARY Nuclear labeling of the carcinoma cells for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA strongly suggests that the primary is nasopharyngeal.

-

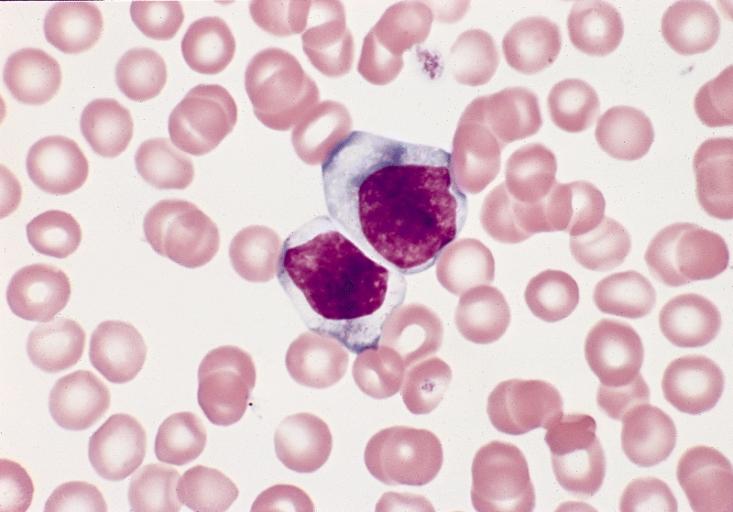

BONE MARROW: REACTIVE (ATYPICAL) LYMPHOCYTES This blood smear is from a 19-year-old male college student with infectious mononucleosis. The two reactive (atypical) lymphocytes are large, with abundant cytoplasm and coarse nuclear chromatin, and lack a nucleolus. Cytoplasmic basophilia is radial in distribution and accentuated at the cell margin. In contrast, lymphoblasts are generally smaller, have less cytoplasm with uniform basophilia and more dispersed nuclear chromatin, and may contain a nucleolus. (Wright-Giemsa stain)

-

LYMPH NODE: INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS, LYMPH NODE

-

BLOOD: INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS; PERIPHERAL BLOOD

-

EYE AND OCULAR ADNEXA: BURKITT LYMPHOMA Bilateral involvement.

-

EYE AND OCULAR ADNEXA: BURKITT LYMPHOMA Lymphoblastic tumor with numerous mitotic figures.

References

- ↑ "Mononucleosis -- Causes". eMedicineHealth. 12/7/2007. Retrieved 2008-03-01. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, Vollmer-Conna U, Cameron B, Vernon SD, Reeves WC, Lloyd A; Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2006 Sep 16;333(7568):575

- ↑ Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, Vollmer-Conna U, Cameron B, Vernon SD, Reeves WC, Lloyd A; Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2006 Sep 16;333(7568):575