Lyme disease historical perspective

|

Lyme disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Lyme disease historical perspective On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Lyme disease historical perspective |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Lyme disease historical perspective |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Ilan Dock, B.S.

Overview

Lyme disease was first described in 1983 by Alfred Buchwald. Later Arvid Afzelius proposed that it was spread by Ixodes tick. The full syndrome now known as Lyme disease was recognized when a number of cases originally thought to be juvenile rheumatoid arthritis was identified in three towns in southeastern Connecticut in 1975, including the towns Lyme and Old Lyme, which gave the disease its popular name.[1]

Historical Perspective

Early History

- The first record of a condition associated with Lyme disease dates to 1883 in Breslau (formerly in Germany) where physician Alfred Buchwald described a degenerative skin disorder now known as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. In 1909, Arvid Afzelius presented research about an expanding, ring-like lesion he had observed. Afzelius published his work 12 years later and speculated that the rash came from the bite of an Ixodes tick, and that meningitic symptoms and signs occur in a number of cases; this rash is now known as erythema migrans (EM), the skin rash found in early stage Lyme disease.[2] In 1911, parasitologist Andrew Balfour of the Wellcome Research Laboratory in Khartoum identified "infective granules" or spore-type "cysts" as the cause of persistence of spirochetal infection in the Sudanese Fowl.[3]

- In the 1920s, French physicians Garin and Bujadoux described a patient with meningoencephalitis, painful sensory radiculitis, and erythema migrans following a tick bite, and they postulated the symptoms were due to a spirochetal infection. In the 1940s, German neurologist Alfred Bannwarth described several cases of chronic lymphocytic meningitis and polyradiculoneuritis, some of which were accompanied by erythematous skin lesions.

- In 1948 spirochete-like structures were observed in skin specimens by Swedish dermatologist Carl Lennhoff.[4] In the 1950s, relations between tick bite, lymphocytoma, EM and Bannwarth's syndrome are seen throughout Europe leading to the use of penicillin for treatment.[5][6][7]

- Interest in tick-borne infections in the U.S. began with the first report of tick-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia hermsii) in 1915, following the recognition of five human patients in Colorado.[8]

- In 1970 a physician in Wisconsin named Rudolph Scrimenti reports the first case of EM in U.S. and treats it with penicillin based on European literature.[9]

- The full syndrome now known as Lyme disease was not recognized until a cluster of cases originally thought to be juvenile rheumatoid arthritis was identified in three towns in southeastern Connecticut in 1975, including the towns Lyme and Old Lyme, which gave the disease its popular name.[10] This was investigated by Dr. David Snydman and Dr. Allen Steere of the Epidemic Intelligence Service, and by others from Yale University. The recognition that the patients in the United States had EM led to the recognition that "Lyme arthritis" was one manifestation of the same tick-borne condition known in Europe.[11]

- Before 1976, elements of B. burgdorferi sensu lato infection were called or known as tickborne meningopolyneuritis, Garin-Bujadoux syndrome, Bannworth syndrome, Afzelius syndrome, Montauk Knee or sheep tick fever. Since 1976 the disease is most often referred to as Lyme disease,[12][13] Lyme borreliosis or simply borreliosis.

- In 1976, Jay Sanford, a former physician at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, published a chapter in the book The Biology of Parasitic Spirochetes. In it, Dr. Sanford stated: "the ability of borrelia, especially tick-borne strains, to persist in the brain and in the eye during remission after treatment with arsenic or with penicillin or even after apparent cure, is well known.” [14] Although the notion of persistent neurological infection was identified early on by military researchers such as Dr. Sanford, later Lyme researchers curiously denied the possibility of persistent Borrelia infection in the brain, with many researchers ignoring evidence of persistent infection.

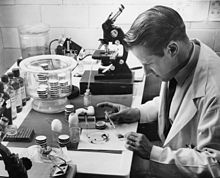

- In 1980 Steere, et al, began to test antibiotic regimens in adult patients with Lyme disease.[15] In 1982 a novel spirochete was cultured from the mid-gut of Ixodes ticks in Shelter Island, New York, and subsequently from patients with Lyme disease. The infecting agent was then identified by Jorge Benach at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and soon after isolated by Willy Burgdorfer, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health, who specialized in the study of spirochete microorganisms such as Borrelia and Rickettsia. The spirochete was named Borrelia burgdorferi in his honor. Burgdorfer was the partner in the successful effort to culture the spirochete, along with Alan Barbour.

- After identification B. burgdorferi as the causative agent of Lyme disease, antibiotics were selected for testing, guided by in vitro antibiotic sensitivities, including tetracycline antibiotics, amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, intravenous and intramuscular penicillin and intravenous ceftriaxone.[16][17] The mechanism of tick transmission was also the subject of much discussion. B. burgdorferi spirochetes were identified in tick saliva in 1987, confirming the hypothesis that transmission occurred via tick salivary glands.[18]

Recent Developments

- Most clinicians agree on the treatment of early Lyme disease infections.[19] There is, however, considerable disagreement regarding prevalence of the disease, diagnostic criteria, treatment of late-stage Lyme disease, and the likelihood of a chronic, antibiotic-resistant infections. Some authorities contend that Lyme disease is relatively rare, easily diagnosed with available blood tests, and most often easily treated with two to four weeks of antibiotics,[20] while others propose that the disease is under-diagnosed, available blood tests are unreliable, and that extended antibiotic treatment is often necessary.[21][22][23]

- The majority of public health agencies such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control maintain the former position. While this narrower position is sometimes described as the "mainstream" view of Lyme disease, published studies involving non-randomized surveys of physicians in endemic areas found physicians evenly split in their views, with the majority recognizing seronegative Lyme disease, and roughly half prescribing extended courses of antibiotics for chronic Lyme disease.[24][25]

- In recent years a few prominent American Lyme researchers have received funding for the study of organisms that may have previously been used as bioweapons that could be used in bioterrorism attacks. The funding has been granted by various U.S. Government agencies including the National Institute of Health (NIH), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

- For some, these grants have become a source of controversy. They argue that these researchers have a conflict of interest in receiving these U.S. Government funds due to the politicization of Lyme disease and their roles in the history of the controversy, others point out that the grants are warranted as the infectious agents that the researchers are studying for bioterror defense are similar in genetic makeup and pathogenesis of Borrelia, such as tularemia, brucellosis and Q fever. Nonetheless, although confusion exists, federal grants such as these comprise the main mechanism whereby infectious disease research is funded in the U.S.

- In October 2006, further controversy erupted with the release of updated diagnosis and treatment guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).[26] The new IDSA recommendations are more restrictive than prior IDSA treatment guidelines for Lyme,[27] and now require either an EM rash or positive laboratory tests for diagnosis; seronegative Lyme disease is no longer acknowledged (except incidentally in early Lyme disease). The authors of the guidelines maintain that chronic Lyme disease does not result from persistent infection, and therefore treatment beyond 2-4 weeks is not recommended, even in late stage cases. An opposing viewpoint has been expressed by the International Lyme and Associated Disease Society (ILADS), which proposes extended antibiotic treatment beyond four weeks for both early and late Lyme disease.[28]

References

- ↑ Steere AC (2006). "Lyme borreliosis in 2005, 30 years after initial observations in Lyme Connecticut". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 118 (21–22): 625–33. doi:10.1007/s00508-006-0687-x. PMID 17160599.

- ↑ Lipschütz B (1931). "Zur Kenntnis der "Erythema chronicum migrans"". Acta dermato-venereologica (in German). 12: 100–2.

- ↑ Balfour A (1911). "The Infective Granule in Certain Protozoa Infections, as Illustrated by the Spirochaetosis of Sudanese Fowls". THe British Medical Journal: 1296.

- ↑ Lenhoff C (1948). "Spirochetes in aetiologically obscure diseases". Acta Dermato-Venreol. 28: 295–324.

- ↑ Bianchi GE (1950). "Penicillin therapy of lymphocytoma". Dermatologica. 100 (4–6): 270–3. PMID 15421023.

- ↑ Hollstrom E (1951). "Successful treatment of erythema migrans Afzelius". Acta Derm. Venereol. 31 (2): 235–43. PMID 14829185.

- ↑ Paschoud JM (1954). "Lymphocytoma after tick bite". Dermatologica (in German). 108 (4–6): 435–7. PMID 13190934.

- ↑ Meador CN (1915). "Five cases of relapsing fever originating in Colorado, with positive blood findings in two". Colorado Medicine. 12: 365–9.

- ↑ Scrimenti RJ (1970). "Erythema chronicum migrans". Archives of dermatology. 102 (1): 104–5. PMID 5497158.

- ↑ Steere AC (2006). "Lyme borreliosis in 2005, 30 years after initial observations in Lyme Connecticut". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 118 (21–22): 625–33. doi:10.1007/s00508-006-0687-x. PMID 17160599.

- ↑ Sternbach G, Dibble C (1996). "Willy Burgdorfer: Lyme disease". J Emerg Med. 14 (5): 631–4. PMID 8933327.

- ↑ Mast WE, Burrows WM (1976). "Erythema chronicum migrans and "Lyme arthritis"". JAMA. 236 (21): 2392. PMID 989847.

- ↑ Steere AC, Malawista SE, Snydman DR; et al. (1977). "Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three connecticut communities". Arthritis Rheum. 20 (1): 7–17. PMID 836338.

- ↑ Sanford JP (1976). "Relapsing Fever—Treatment and Control". In Johnson RC (ed). Biology of Parasitic Spirochetes. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123870506.

- ↑ Steere AC, Hutchinson GJ, Rahn DW; et al. (1983). "Treatment of the early manifestations of Lyme disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 99 (1): 22–6. PMID 6407378.

- ↑ Luft BJ, Volkman DJ, Halperin JJ, Dattwyler RJ (1988). "New chemotherapeutic approaches in the treatment of Lyme borreliosis". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 539: 352–61. PMID 3056203.

- ↑ Dattwyler RJ, Volkman DJ, Conaty SM, Platkin SP, Luft BJ (1990). "Amoxycillin plus probenecid versus doxycycline for treatment of erythema migrans borreliosis". Lancet. 336 (8728): 1404–6. PMID 1978873.

- ↑ Ribeiro JM, Mather TN, Piesman J, Spielman A (1987). "Dissemination and salivary delivery of Lyme disease spirochetes in vector ticks (Acari: Ixodidae)". J. Med. Entomol. 24 (2): 201–5. PMID 3585913.

- ↑ Murray T, Feder H (2001). "Management of tick bites and early Lyme disease: a survey of Connecticut physicians". Pediatrics. 108 (6): 1367–70. PMID 11731662.

- ↑ Wormser G (2006). "Clinical practice. Early Lyme disease". N Engl J Med. 354 (26): 2794–801. PMID 16807416.

- ↑ Stricker RB, Lautin A, Burrascano JJ (2006). "Lyme Disease: The Quest for Magic Bullets". Chemotherapy. 52 (2): 53–59. PMID 16498239.

- ↑ Phillips SE, Harris NS, Horowitz R, Johnson L, Stricker RB (2005). "Lyme disease: scratching the surface". Lancet. 366 (9499): 1771. PMID 16298211.

- ↑ Phillips S, Bransfield R, Sherr V, Brand S, Smith H, Dickson K, and Stricker R (2003). "Evaluation of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms of Lyme disease: an ILADS position paper" (PDF). International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society. Retrieved 2006-03-15.

- ↑ Ziska MH, Donta ST, Demarest FC (1996). "Physician preferences in the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease in the United States". Infection. 24 (2): 182–6. PMID 8740119.

- ↑ Eppes SC, Klein JD, Caputo GM, Rose CD (1994). "Physician beliefs, attitudes, and approaches toward Lyme disease in an endemic area". Clin Pediatr (Phila). 33 (3): 130–4. PMID 8194286.

- ↑ "New Lyme Disease Guidelines Spark Showdown". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ↑ Wormser G, Dattwyler R, Shapiro E; et al. (2006). "The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin Infect Dis. 43 (9): 1089–134. PMID 17029130.

- ↑ "Treatment guidelines". International Lyme and Associated Disease Society. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- CS1 maint: Unrecognized language

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list

- Needs overview

- Bacterial diseases

- Insect-borne diseases

- Lyme disease

- Zoonoses

- Spirochaetes

- Disease

- Infectious disease

- Dermatology

- Emergency medicine

- Intensive care medicine