Irritable bowel syndrome pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

m (Categories) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

==Pathophysiology== | ==Pathophysiology== | ||

Initially, IBS was considered a psychosomatic illness, and the involvement of biological and pathogenic factors was not verified until the 1990s, a process common in the [[history of emerging infectious diseases]]. The risk of developing IBS increases six-fold after acute gastrointestinal infection. Post-infection, further risk factors are young age, prolonged fever, anxiety and depression.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Thabane M, Kottachchi DT, Marshall JK | title = The incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. | journal = Aliment Pharmacol Ther | volume = 26 | issue = 4 | pages = 535-44 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17661757}}</ref> | Initially, IBS was considered a psychosomatic illness, and the involvement of biological and pathogenic factors was not verified until the 1990s, a process common in the [[history of emerging infectious diseases]]. The risk of developing IBS increases six-fold after acute gastrointestinal infection. Post-infection, further risk factors are young age, prolonged [[fever]], [[anxiety]] and [[depression]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Thabane M, Kottachchi DT, Marshall JK | title = The incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. | journal = Aliment Pharmacol Ther | volume = 26 | issue = 4 | pages = 535-44 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17661757}}</ref> | ||

===Psychosomatic illness=== | ===Psychosomatic illness=== | ||

Revision as of 13:38, 7 February 2017

|

Irritable bowel syndrome Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Irritable bowel syndrome from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Irritable bowel syndrome pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Irritable bowel syndrome pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Irritable bowel syndrome pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]

Overview

Pathophysiology

Initially, IBS was considered a psychosomatic illness, and the involvement of biological and pathogenic factors was not verified until the 1990s, a process common in the history of emerging infectious diseases. The risk of developing IBS increases six-fold after acute gastrointestinal infection. Post-infection, further risk factors are young age, prolonged fever, anxiety and depression.[1]

Psychosomatic illness

One of the first references to the concept of an "Irritable Bowel" appeared in the Rocky Mountain Medical Journal in 1950.[2] The term was used to categorize patients who developed symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation, but where no well-recognized infective cause could be found. Early theories suggested that the Irritable Bowel was caused by a somatic, or mental disorder. One paper from the 1980s investigated "learned illness behavior" in patients with IBS and peptic ulcers.[3] Another study suggested that both IBS and stomach ulcer patients would benefit from 15 months of psychotherapy.[4] Later, it was found that most stomach ulcers were caused by a bacterial infection with Helicobacter pylori.[5]

Additional publications suggesting the role of brain-gut "axis" appeared in the 1990s, such as a study entitled Brain-gut response to stress and cholinergic stimulation in IBS published in the Journal of Clinical Gastrotnerology in 1993.[6] A 1997 study published in Gut magazine suggested that IBS was associated with a "derailing of the brain-gut axis."[7]

Immune reaction

From the late 1990s, research publications began identifying specific biochemical changes present in tissue biopsies and serum samples from IBS patients that suggested symptoms had an organic rather than psychosomatic cause. These studies identified cytokines and secretory products in tissues taken from IBS patients. The cytokines identified in IBS patients produce inflammation and are associated with the body's immune response.

- A study showed that intestinal biopsies from patients with constipation predominant IBS secreted higher levels of serotonin in-vitro.[9] Serotonin plays a role in regulating gastrointestinal motility and water content and can be altered by some diseases and infections.[10][11][12]

- A study of rectal biopsy tissue from IBS patients showed increased levels of cellular structures involved in the production of the cytokine Interleukin 1 Beta.[13]

- A study of blood samples from IBS patients identified elevated levels of cytokines Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, Interleukin 1, and Interleukin 6 in patients with IBS.[14]

- A study of intestinal biopsies from IBS patients showed increased levels of protease enzymes used by the body to digest proteins, and by infectious agents to combat the host's immune system.[15]

- A study of blood samples from IBS patients found elevated levels of antibodies to the protozoan Blastocystis.[16]

Specific forms of immune response that have been implicated in IBS symptoms include coeliac disease and other food allergy conditions.[17] Coeliac disease (also spelled "celiac") is an immunoglobulin type A-(IgA) mediated allergic response to the gliadin protein in gluten grains,which exhibits wide variety of symptoms and can present as IBS. "Some patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) may have undiagnosed celiac sprue (CS). Because the symptoms of CS respond to a gluten-free diet, testing for CS in IBS may prevent years of morbidity and attendant expense."[18] "Coeliac disease is a common finding among patients labelled as having irritable bowel syndrome. In this sub-group, a gluten free diet may lead to a significant improvement in symptoms. Routine testing for coeliac disease may be indicated in all patients being evaluated for irritable bowel syndrome."[19] Food allergies, particularly those mediated by IgE and IgG-type antibodies have been implicated in IBS.[20][21][22]

Active infections

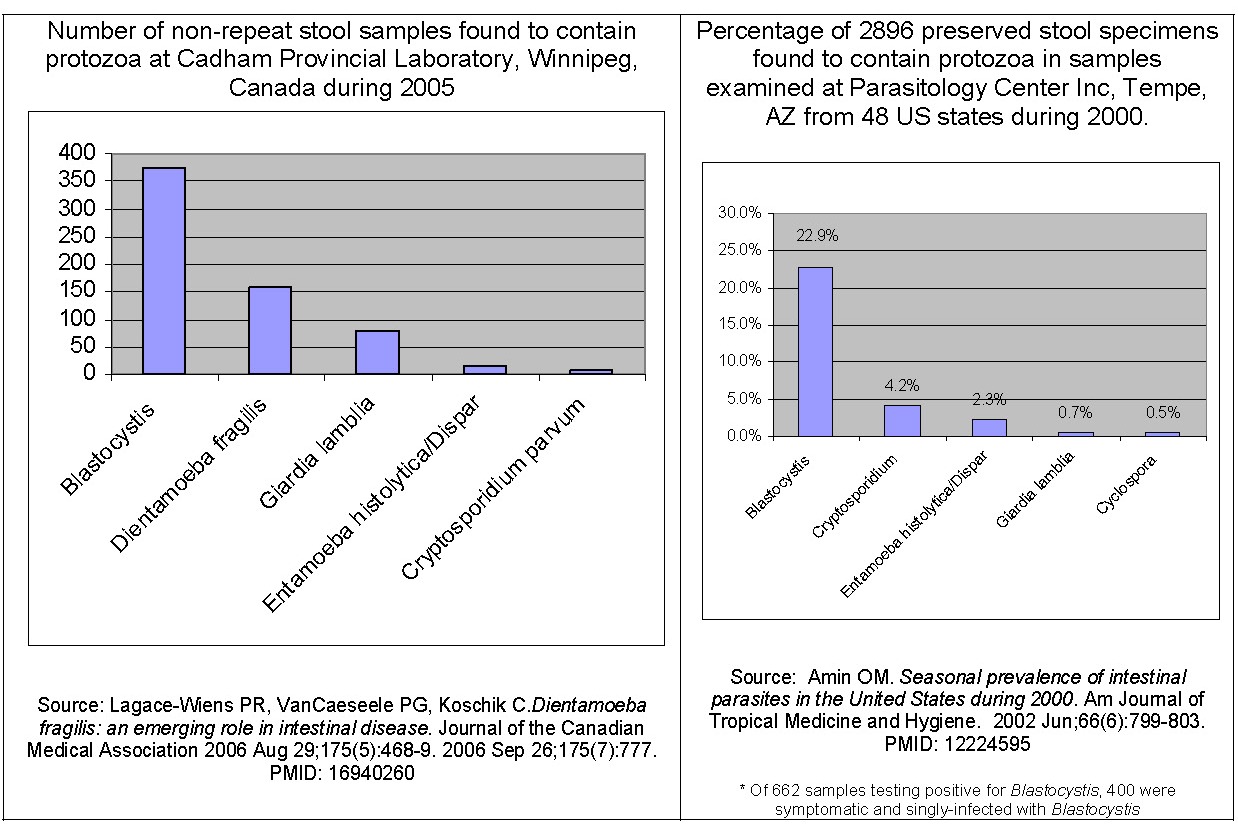

There is research to support IBS being caused by an as-yet undiscovered active infection. Most recently, a study has found that the antibiotic Rifaximin provides sustained relief for IBS patients.[23] While some researchers see this as evidence that IBS is related to an undiscovered agent, others believe IBS patients suffer from overgrowth of intestinal flora and the antibiotics are effective in reducing the overgrowth (known as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth).[24] Other researchers have focused on an unrecognized protozoal infection as a cause of IBS[25] as certain protozoal infections occur more frequently in IBS patients.[26][27] Two of the protozoa investigated have a high prevalence in industrialized countries and infect the bowel, but little is known about them as they are recently emerged pathogens.

Blastocystis is a single-celled organism which has been reported to produce symptoms of abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhea in patients, along with headaches and depression,[28] though these reports are contested by some physicians.[29] Studies from research hospitals in various countries have identified high Blastocystis infection rates in IBS patients, with 38% being reported from London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine,[30] 47% reported from the Department of Gastroenterology at Aga Khan University in Pakistan[26] and 18.1% reported from the Institute of Diseases and Public Health at University of Ancona in Italy.[27] Reports from all three groups indicate a Blastocystis prevalence of approximately 7% in non-IBS patients. Researchers have noted that clinical diagnostics fail to identify infection,[31] and Blastocystis may not respond to treatment with common antiprotozoals.[32][33][34][35]

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled organism which produces abdominal pain and diarrhea. Studies have reported a high incidence of infection in developed countries, and symptoms of patients resolve following antibiotic treatment.[36][38] One study reported on a large group of patients with IBS-like symptoms who were found to be infected with Dientamoeba fragilis and experienced resolution of symptoms following treatment.[39] Researchers have noted that methods used clinically may fail to detect some Dientamoeba fragilis infections.[38]

References

- ↑ Thabane M, Kottachchi DT, Marshall JK (2007). "The incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 26 (4): 535–44. PMID 17661757.

- ↑ BROWN PW (1950). "The irritable bowel syndrome". Rocky Mountain medical journal. 47 (5): 343–6. PMID 15418074.

- ↑ Whitehead WE, Winget C, Fedoravicius AS, Wooley S, Blackwell B (1982). "Learned illness behavior in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer". Dig. Dis. Sci. 27 (3): 202–8. PMID 7075418.

- ↑ Svedlund J, Sjödin I (1985). "A psychosomatic approach to treatment in the irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease with aspects of the design of clinical trials". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 109: 147–51. PMID 3895386.

- ↑ Damianos AJ, McGarrity TJ (1997). "Treatment strategies for Helicobacter pylori infection". American family physician. 55 (8): 2765–74, 2784–6. PMID 9191460.

- ↑ Fukudo S, Nomura T, Muranaka M, Taguchi F (1993). "Brain-gut response to stress and cholinergic stimulation in irritable bowel syndrome. A preliminary study". J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 17 (2): 133–41. PMID 8031340.

- ↑ Orr WC, Crowell MD, Lin B, Harnish MJ, Chen JD (1997). "Sleep and gastric function in irritable bowel syndrome: derailing the brain-gut axis". Gut. 41 (3): 390–3. PMID 9378397.

- ↑ El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH; et al. (2000). "Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer". Nature. 404 (6776): 398–402. doi:10.1038/35006081. PMID 10746728.

- ↑ Miwa J, Echizen H, Matsueda K, Umeda N (2001). "Patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may have elevated serotonin concentrations in colonic mucosa as compared with diarrhea-predominant patients and subjects with normal bowel habits". Digestion. 63 (3): 188–94. PMID 11351146.

- ↑ McGowan K, Kane A, Asarkof N; et al. (1983). "Entamoeba histolytica causes intestinal secretion: role of serotonin". Science. 221 (4612): 762–4. PMID 6308760.

- ↑ McGowan K, Guerina V, Wicks J, Donowitz M (1985). "Secretory hormones of Entamoeba histolytica". Ciba Found. Symp. 112: 139–54. PMID 2861068.

- ↑ Banu, Naheed; et al. (2005). "Neurohumoral alterations and their role in amoebiasis" (PDF). Indian J. Clin Biochem. 20 (2): 142–5.

- ↑ Gwee KA, Collins SM, Read NW; et al. (2003). "Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1beta in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome". Gut. 52 (4): 523–6. PMID 12631663.

- ↑ Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C; et al. (2007). "Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome". Gastroenterology. 132 (3): 913–20. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.046. PMID 17383420.

- ↑ Cenac N, Andrews CN, Holzhausen M; et al. (2007). "Role for protease activity in visceral pain in irritable bowel syndrome". J. Clin. Invest. 117 (3): 636–47. doi:10.1172/JCI29255. PMID 17304351.

- ↑ Hussain R, Jaferi W, Zuberi S; et al. (1997). "Significantly increased IgG2 subclass antibody levels to Blastocystis hominis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56 (3): 301–6. PMID 9129532.

- ↑ Wangen, Dr. Stephen. The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Solution. 2006. ISBN 0976853787. Excerpted with author's permission at [1]

- ↑ Spiegel BM; et al. (2004). "Testing for celiac sprue in irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea: a cost-effectiveness analysis". Gastroenterology. 126 (7): 1721–32. PMID 15188167.

- ↑ Shahbazkhani B; et al. (2003). "Coeliac disease presenting with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome". Aliment Pharmacol Therapy. 18 (2): 231–5. PMID 12869084.

- ↑ Li H; et al. (2007). "Allergen-IgE complexes trigger CD23-dependent CCL20 release from human intestinal epithelial cells". Gastroenterology. 133 (6): 1905–15. PMID 18054562.

- ↑ "The therapeutic effects of eliminating allergic foods according to food-specific IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome - Article in Chinese". Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 46 (8): 641–3. 2007. PMID 17967233. Text "Yang CM, Li YQ " ignored (help)

- ↑ Drisko; et al. (2006). "Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome with a Food Elimination Diet Followed by Food Challenge and Probiotics". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 25 (6): 514–22. PMID 17229899.

- ↑ Pimentel M, Park S, Mirocha J, Kane SV, Kong Y (2006). "The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 145 (8): 557–63. PMID 17043337.

- ↑ Posserud I, Stotzer PO, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M (2007). "Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome". Gut. 56 (6): 802–8. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.108712. PMID 17148502.

- ↑ Stark D, van Hal S, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J (2007). "Irritable bowel syndrome: a review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis". Int. J. Parasitol. 37 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.09.009. PMID 17070814.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Yakoob J, Jafri W, Jafri N; et al. (2004). "Irritable bowel syndrome: in search of an etiology: role of Blastocystis hominis". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70 (4): 383–5. PMID 15100450.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Fiorentini A, Fortuna M, Scalise G (1999). "Irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Blastocystis hominis infection". Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18 (6): 436–9. PMID 10442423.

- ↑ Qadri SM, al-Okaili GA, al-Dayel F (1989). "Clinical significance of Blastocystis hominis". J. Clin. Microbiol. 27 (11): 2407–9. PMID 2808664.

- ↑ Markell EK, Udkow MP (1986). "Blastocystis hominis: pathogen or fellow traveler?". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 35 (5): 1023–6. PMID 3766850.

- ↑ Windsor J (2007). "B. hominis and D. fragilis: Neglected human protozoa". British Biomedical Scientist: 524–7.

- ↑ Stensvold R, Brillowska-Dabrowska A, Nielsen HV, Arendrup MC (2006). "Detection of Blastocystis hominis in unpreserved stool specimens by using polymerase chain reaction". J. Parasitol. 92 (5): 1081–7. PMID 17152954.

- ↑ Yakoob J, Jafri W, Jafri N, Islam M, Asim Beg M (2004). "In vitro susceptibility of Blastocystis hominis isolated from patients with irritable bowel syndrome". Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 61 (2): 75–7. PMID 15250669.

- ↑ Haresh K, Suresh K, Khairul Anus A, Saminathan S (1999). "Isolate resistance of Blastocystis hominis to metronidazole". Trop. Med. Int. Health. 4 (4): 274–7. PMID 10357863.

- ↑ Markell EK, Udkow MP (1986). "Blastocystis hominis: pathogen or fellow traveler?". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 35 (5): 1023–6. PMID 3766850.

- ↑ Ok UZ, Girginkardeşler N, Balcioğlu C, Ertan P, Pirildar T, Kilimcioğlu AA (1999). "Effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethaxazole in Blastocystis hominis infection". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94 (11): 3245–7. PMID 10566723.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Lagacé-Wiens PR, VanCaeseele PG, Koschik C (2006). "Dientamoeba fragilis: an emerging role in intestinal disease". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 175 (5): 468–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060265. PMID 16940260.

- ↑ Amin OM (2002). "Seasonal prevalence of intestinal parasites in the United States during 2000". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66 (6): 799–803. PMID 12224595.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Stensvold CR, Arendrup MC, Mølbak K, Nielsen HV (2007). "The prevalence of Dientamoeba fragilis in patients with suspected enteroparasitic disease in a metropolitan area in Denmark". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13 (8): 839–42. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01760.x. PMID 17610603.

- ↑ Borody T, Warren E, Wettstein A; et al. (2002). "Eradication of Dientamoeba fragilis can resolve IBS-like symptoms". J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 17 (Suppl, pages=A103).