Cervical cancer pathophysiology

|

Cervical cancer Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cervical cancer pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cervical cancer pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Cervical cancer pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]}Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Monalisa Dmello, M.B,B.S., M.D. [2]

Pathophysiology

Molecular pathogenesis of cervical cancer

Human papillomaviruses subtypes 16 and 18 play an essential role in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. HPV subtypes 16 and 18 deregulate the genes E6 and E7 which code for proteins that inhibit p53 and Retinoblastoma protein (Rb), which are two important tumor suppressor genes in humans. The p53 gene product is involved in regulation of apoptosis (cell suicide), and Rb is responsible for halting the cell cycle at the G1-phase. When Rb function is impaired, the cell is allowed to progress to S-phase and complete mitosis, resulting in proliferation and hence neoplastic transformation.

Pathogenesis

Cervical carcinoma has its origins at the squamous-columnar junction; it can involve the outer squamous cells, the inner glandular cells, or both. The precursor lesion is dysplasia: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or adenocarcinoma in situ, which can subsequently become invasive cancer. This process can be quite slow. Longitudinal studies have shown that in patients with untreated in situ cervical cancer, 30% to 70% will develop invasive carcinoma over a period of 10 to 12 years. However, in about 10% of patients, lesions can progress from in situ to invasive in a period of less than 1 year. As it becomes invasive, the tumor breaks through the basement membrane and invades the cervical stroma. Extension of the tumor in the cervix may ultimately manifest as ulceration, exophytic tumor, or extensive infiltration of underlying tissue, including the bladder or rectum.

Microscopic Pathology

-

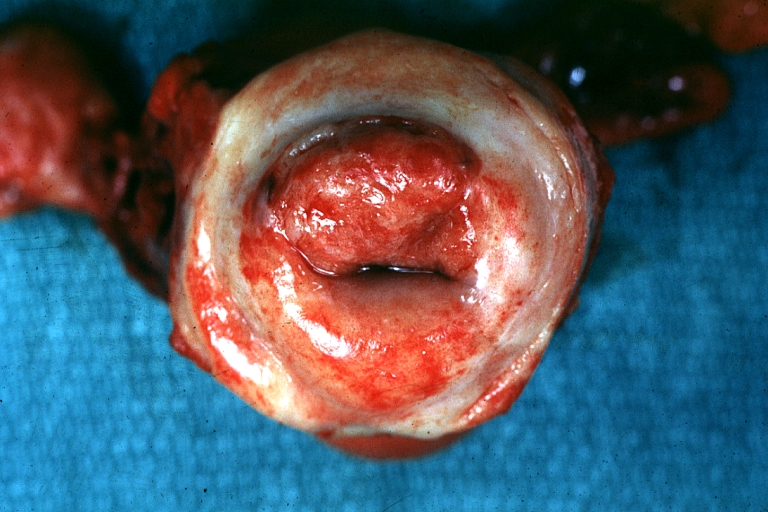

Uterus: Cervical Carcinoma: Gross, an excellent example of tumor (labeled as invasive)

Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology -

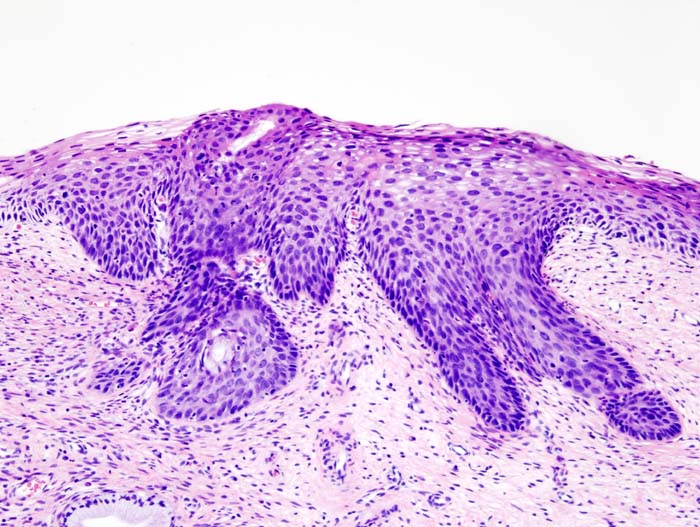

Histopathologic image (H&E stain) of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Video

{{#ev:youtube|J3kULzKGzws}}