Blastomycosis pathophysiology

|

Blastomycosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Blastomycosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Blastomycosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Blastomycosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: ; Vidit Bhargava, M.B.B.S [2]

Overview

Pathophysiology

Transmission

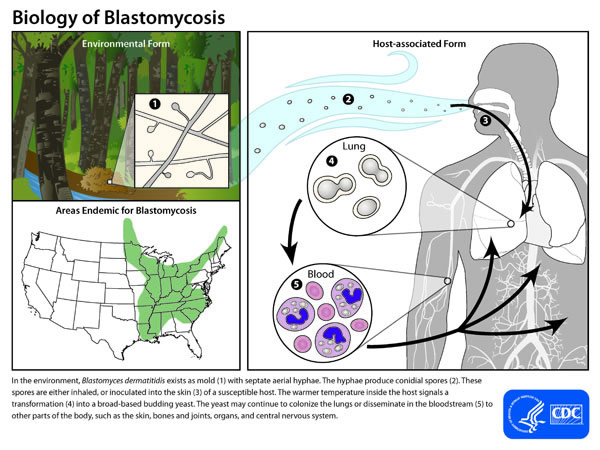

- Inhalation of the conidia from its natural soil habitat is considered the most significant route of transmission.[1]

- Other less common route of transmission is by cutaneous inoculation through direct skin injury.[2]

Incubation

- The incubation period varies from 3 weeks to 3 months after exposure.

Pathogensis

- Once inhaled in the lungs, the conidia are mostly destroyed due to their susceptibility to neutrophils, leukocytes and macrophages. [3]

- However, a few conidia escape this protective mechanism and evolve into yeast form, which being double walled structures are more resistant to destruction.

- This conversion releases a glycoprotien BAD-1, which induces cell mediated immunity. [4]

- This results in a pyogranulomatous response at the site of infection (lungs).

- Which eventually leads to the formation of a non-caseating granulomas.

Dissemination

- The fungi can disseminate through the blood and lymphatics to other organs, including the skin, bone, genitourinary tract.[1]

Immune response

- Cyototxic T cells are mainly responsible for persistence of infection and tissue damage.

- Ineffective type 4 delayed hypersensitivity reaction containing macrophages and sensitized T cells are mainly responsible for the cutaneous manifestations. [4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Saccente M, Woods GL (2010). "Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 (2): 367–81. doi:10.1128/CMR.00056-09. PMC 2863359. PMID 20375357.

- ↑ Smith JA, Riddell J, Kauffman CA (2013). "Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses". Curr Infect Dis Rep. 15 (5): 440–9. doi:10.1007/s11908-013-0352-2. PMID 23917880.

- ↑ Kauffman, Carol (2011). Essentials of clinical mycology. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-6639-1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Koneti A, Linke MJ, Brummer E, Stevens DA (2008). "Evasion of innate immune responses: evidence for mannose binding lectin inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha production by macrophages in response to Blastomyces dermatitidis". Infect. Immun. 76 (3): 994–1002. doi:10.1128/IAI.01185-07. PMC 2258846. PMID 18070904.