Acute respiratory distress syndrome overview

|

Acute respiratory distress syndrome Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Acute respiratory distress syndrome from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Acute respiratory distress syndrome overview On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Acute respiratory distress syndrome overview |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Acute respiratory distress syndrome overview |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), also known as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) or adult respiratory distress syndrome (in contrast with infant respiratory distress syndrome, or IRDS) is a serious and potentially life-threatening inflammatory lung condition that may occur in the setting of infection, toxic exposure, adverse drug reactions, trauma, or overall critical illness. ARDS is characterized by inflammation of the lung parenchyma resulting in increased permeability of the alveolar-capillary membrane, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, impaired gas exchange, and decreased lung compliance.

ARDS may be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the magnitude of impaired oxygenation; however, even mild ARDS may progress to multiple organ failure if appropriate measures to improve oxygenation are not taken. The vast majority of patients diagnosed with ARDS are managed in an intensive care unit, and most will require mechanical ventilation at some point during the course of their illness and recovery.

Below is a table showing The Berlin definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome:[1]

| Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Timing | ❑ Within 1 week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms |

| Chest imaging i.e., CXR or CT |

❑ Bilateral opacities—not fully explained by effusions, lobar/lung collapse, or

nodules |

| Origin of edema | ❑ Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload ❑ Need objective assessment (e.g., echocardiography) to exclude hydrostatic edema if no risk factor present |

| Oxygenation (Corrected for altitude) |

|

| Mild | ❑ 200 mm Hg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg with PEEP or CPAP > 5 cm H2O |

| Moderate | ❑ 100 mm Hg < PaO2/FIO2 ≤ 200 mm Hg with PEEP ≥ 5 cm H2O |

| Severe | ❑ PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mm Hg with PEEP ≥ 5 cm H2O |

ARDS usually occurs within 24 to 48 hours of the initial injury or illness. The patient usually presents with shortness of breath, tachypnea, and symptoms related to the underlying cause, i.e. shock.

An arterial blood gas analysis and chest X-ray allow formal diagnosis by inference using the aforementioned criteria. Although severe hypoxemia is generally included, the appropriate threshold defining abnormal PaO2 has never been systematically studied.

Any cardiogenic cause of pulmonary edema should be excluded. This can be done by placing a pulmonary artery catheter for measuring the pulmonary artery wedge pressure. However, this is not necessary and is now rarely done as abundant evidence has emerged demonstrating that the use of pulmonary artery catheters does not lead to improved patient outcomes in critical illness including ARDS.

While CT scanning leads to more accurate images of the pulmonary parenchyma in ARDS, its has little utility in the clinical management of patients with ARDS, and remains largely a research tool. Plain Chest X-rays are sufficient to document bilateral alveolar infiltrates in the majority of cases

Historical Perspective

Although the first pathologic descriptions of what was likely ARDS date back to the 19th century, our understanding of the distinct pathophysiologic features of ARDS evolved alongside the development of medical technologies that facilitated a more in-depth study of the syndrome. The advent of radiography permitted visualization of the bilateral pulmonary infiltrates (originally termed double pneumonia), while the development of arterial blood gas measurement and positive-pressure mechanical ventilation allowed for identification of the impaired oxygenation and reduced lung compliance that are now recognized as central features of ARDS.[2]

Ashbaugh and colleagues published he first description of what is now widely recognized as ARDS in a case series of 12 patients with rapidly progressive respiratory failure with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and profound hypoxemia following trauma or infection in The Lancet in 1967.[3] The clinical syndrome was called the "adult respiratory distress syndrome" (ARDS) to distinguish it from the respiratory distress syndrome of infancy due to hyaline membrane disease, although the A in ARDS was later changed from acute to adult once it was recognized that the syndrome could also present in infants as a distinct entity from hyaline membrane disease.

Classification

The current ARDS diagnostic criteria (commonly referred to as the Berlin Criteria or Berlin Definition) were established by the ARDS Definition Task Force in 2012. The Berlin Criteria classify ARDS as mild, moderate, and severe based on the degree of oxygenation impairment and serve as a means of risk-stratifying patients.[1]

Pathophysiology

ARDS typically develops within 24 to 48 hours of the provoking illness or injury and is classically divided into three phases:

- Exudative phase (within 24-48 hours): Systemic inflammation results in increased alveolar capillary permeability and leads to the formation of hyaline membranes along alveolar walls, accumulation of proteinaceous exudate within the alveolar air spaces (non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema), and extravasation of inflammatory cells (predominantly neutrophils and macrophages) into the lung parenchyma, leading to extensive alveolar damage and sometimes hemorrhage into alveoli

- Proliferative phase (within 5-7 days): Fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, and early fibrotic changes are observed within the pulmonary interstitium as alveolar exudate and hyaline membranes begin to be absorbed

- Fibrotic phase (within several weeks): Most patients with ARDS will develop some degree of pulmonary fibrosis, of which at least one-quarter will go on to develop a restrictive ventilatory defect on pulmonary function tests[4]; the development and extent of pulmonary fibrosis in ARDS correlates with an increased mortality risk[5]

Genetic Susceptibility

The role of genetics in the development of ARDS is an ongoing area of research. While studies have demonstrated associations between certain genetic factors (including single-nucleotide polymorphisms and allelic variants of angiotensin-converting enzyme[6],[7]) and increased susceptibility to developing ARDS, the nature and implications of these relationships remain uncertain.[8]

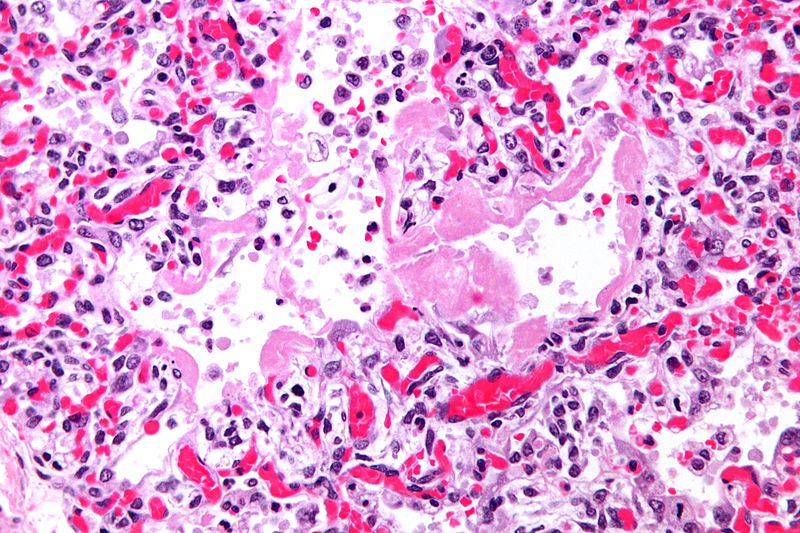

Pathology

- On gross pathology, the lungs are firm, boggy, and dusky, and they typically weigh more than healthy lungs due to edema

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, the lung parenchyma demonstrates hyaline membranes lining the alveolar air spaces, edema fluid within alveoli and the interstitium, shedding of type I pneumocytes and proliferation of type II pneumocytes, infiltration of polymorphonuclear and other inflammatory cells into the interstitial and alveolar compartments, thrombosis and obliteration of pulmonary capillaries, and occasionally hemorrhage into alveoli

- Features specific to the underlying disease process (e.g., bacterial pneumonia or aspiration pneumonitis) are often seen as well

- As ARDS progresses, alveolar infiltrates are reabsorbed and the inflammatory milieu is replaced by increased collagen deposition and proliferating fibroblasts, culminating in interstitial fibrosis

Causes

ARDS may occur as the result of either a direct or indirect insult to the lungs:

- Direct insult: Pneumonia, aspiration pneumonitis, toxic inhalation, physical trauma to the lungs

- Indirect insult: Sepsis, blood transfusion, drug or toxin exposures, traumatic injury, pancreatitis

Sepsis is the most common cause of ARDS, followed by aspiration pneumonitis and transfusion-related acute lung injury[9] Certain medical comorbidities (e.g., chronic liver or kidney disease, alcoholism, infection with the human immunodeficiency virus, prior organ transplantation) predispose to the development of ARDS, and the risk for developing ARDS increases along with the number of acute insults (e.g., pneumonia and pancreatitis versus pancreatitis alone).

Differentiating ARDS from other Diseases

Prior to the development of the Berlin Definition in 2012, a greater emphasis was placed on excluding other potential illnesses prior to making a diagnosis of ARDS. While it is important to recognize and treat and underlying cause of the patient's impaired ventilation and hypoxemia, this search for potential etiologies should not delay any efforts to improve oxygenation and ventilation.

On chest X-ray, the bilateral, non-cardiogenic pulmonary infiltrates of ARDS may appear similar to those of cardiogenic (hydrostatic) pulmonary edema. Therefore, it is necessary to formally assess cardiac function and volume status if ARDS is suspected but no clear precipitating insult (e.g., sepsis, trauma, toxic inhalation) can be identified. The preferred methods for making this assessment in the ICU are:

- Echocardiography to assess heart function

- Central venous catheterization to measure central venous pressure

- Pulmonary artery (Swan-Ganz) catheterization to measure right-sided heart pressures and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (a surrogate of left atrial pressure)

Because ARDS is a clinical syndrome that, by definition, occurs in the setting of another illness or insult, identification and treatment of the underlying cause of ARDS is essential. Some standard components of this workup include:

- Chest X-ray

- Arterial blood gases

- Complete blood count with differential

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, and tests of liver function)

- Coagulation markers (partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time with international normalized ratio)

- Blood, sputum, and urine cultures

- Serum lactate

Additional testing should be guided by clinical suspicion and the patient's medical history. These may include such tests as:

- Serum lipase

- Urine or blood toxicology screens

- Blood alcohol level

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screen

- Respiratory virus screen (direct fluorescent antibody or polymerase chain reaction testing)

- Influenza virus testing

- Fungal cultures

- Tests for atypical pathogens that may cause pneumonia, for example:

- Legionella pneumophila culture and urine antigen testing

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae culture and antibody titers

- Pneumocystis jirovecii sputum silver stain and culture

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis sputum smear and culture

Epidemiology and Demographics

The incidence of ARDS in the United States is estimated at around 75 cases per 100,000 person-years, which amounts to roughly 150,000 new cases per year.[10] There is substantial variance in the rates of ARDS between different countries and geographic regions due to factors such as mean life expectancy, prevalence of different risk factors and comorbidities, and access to health care.

Age

- Advanced age is a non-modifiable risk factor for the development of ARDS

Gender

- Some studies have suggested that women are slightly more likely than men to develop ARDS, however, the mortality rate may be slightly higher among men than women[11],[12]

Race

- There does not appear to be a racial predilection for ARDS, however, in the United States the mortality rate among African Americans with ARDS is higher than for whites[11]

Risk Factors

Common risk factors in the development of ARDS are:

- Advanced age

- Chronic alcoholism

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Cigarette smoke exposure

The association between chronic alcoholism and a higher risk of developing ARDS has been demonstrated in several research studies.[13],[14] In one such study, patients with a history of alcohol abuse were roughly twice as likely to develop ARDS and experienced a mortality rate that was 36% higher than age-, sex-, and disease-matched patients without a history of alcohol abuse.[13]

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- ARDS typically occurs within the first week of the precipitating illness or trauma and usually progresses rapidly within the first 24 to 48 hours.

- The early clinical features of ARDS include:

- Hypoxemia (a declining peripheral blood oxygen saturation [SpO2] on pulse oximetry or a declining partial pressure of oxygen [PaO2] on arterial blood gas analysis) requiring high concentrations of supplemental oxygen (i.e., a higher fraction of inspired oxygen [FIO2]) or positive pressure ventilation (i.e., a higher continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] or a higher positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP]) in order to maintain acceptable blood oxygenation

- Tachypnea and labored breathing

- Tachycardia

- Signs or symptoms that suggest worsening of the underlying illness

- Left untreated, the mortality rate from ARDS is estimated to be upwards of 70%.[15] Long-term sequelae are more likely to develop among those who do not receive adequate treatment and include:

- Significant weakness due to muscle atrophy, sometimes leading to lifelong physical disability

- Impaired lung function

- Chronic ventilator dependency

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Psychiatric illness (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], anxiety, and depression)

- Cognitive impairment

- The most common complications of ARDS are those associated with a prolonged ICU stay:

- Secondary or nosocomial infections (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia [VAP] or central line-associated blood stream infection [CLABSI])

- Venous thromboembolic events (e.g., deep vein thrombosis [DVT] or pulmonary embolism [PE])

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Pressure ulcers and poor wound-healing

- Muscle wasting and atrophy

- Prognosis for patients with ARDS varies based on the severity of illness, the precipitating insult, and medical comorbidities:

- The mortality rate among patients with ARDS due to trauma appears to be lower than among patients with ARDS due to sepsis[16]

- The ARDS Definition Task Force calculated 90-day morality rates for mild, moderate, and severe ARDS as 27%, 32%, and 45%, respectively[1]

- One study of patients diagnosed with ARDS in Maryland, United States, from 1992 through 1995 calculated an in-hospital mortality rate of 36% to 52%[15]

- The 1-year mortality rate for patients with ARDS who survive to hospital discharge varies widely between different studies and is estimated to be anywhere from 11% to over 40%[17],[18],[19]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of [disease name] is made when at least [number] of the following [number] diagnostic criteria are met:

| Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome | |

| Timing | ❑ Within 1 week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms |

| Chest imaging a | ❑ Bilateral opacities – not fully explained by effusions, lobar/lung collapse, or nodule |

| Origin of edema | ❑ Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload b |

| Oxygenation c | |

|

❑ 200 mm Hg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg with PEEP or CPAP > 5 cm H2O |

|

❑ 100 mm Hg < PaO2/FIO2 ≤ 200 mm Hg with PEEP ≥ 5 cm H2O |

|

❑ PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mm Hg with PEEP ≥ 5 cm H2O |

- [criterion 1]

- [criterion 2]

- [criterion 3]

- [criterion 4]

Symptoms

- [Disease name] is usually asymptomatic.

- Symptoms of [disease name] may include the following:

- [symptom 1]

- [symptom 2]

- [symptom 3]

- [symptom 4]

- [symptom 5]

- [symptom 6]

Physical Examination

- Patients with [disease name] usually appear [general appearance].

- Physical examination may be remarkable for:

- [finding 1]

- [finding 2]

- [finding 3]

- [finding 4]

- [finding 5]

- [finding 6]

Laboratory Findings

- There are no specific laboratory findings associated with [disease name].

- A [positive/negative] [test name] is diagnostic of [disease name].

- An [elevated/reduced] concentration of [serum/blood/urinary/CSF/other] [lab test] is diagnostic of [disease name].

- Other laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of [disease name] include [abnormal test 1], [abnormal test 2], and [abnormal test 3].

Imaging Findings

- There are no [imaging study] findings associated with [disease name].

- [Imaging study 1] is the imaging modality of choice for [disease name].

- On [imaging study 1], [disease name] is characterized by [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3].

- [Imaging study 2] may demonstrate [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3].

Other Diagnostic Studies

- [Disease name] may also be diagnosed using [diagnostic study name].

- Findings on [diagnostic study name] include [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3].

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- There is no treatment for [disease name]; the mainstay of therapy is supportive care.

- The mainstay of therapy for [disease name] is [medical therapy 1] and [medical therapy 2].

- [Medical therapy 1] acts by [mechanism of action 1].

- Response to [medical therapy 1] can be monitored with [test/physical finding/imaging] every [frequency/duration].

Surgery

- Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] in conjunction with [chemotherapy/radiation] is the most common approach to the treatment of [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] can only be performed for patients with [disease stage] [disease name].

Prevention

- There are no primary preventive measures available for [disease name].

- Effective measures for the primary prevention of [disease name] include [measure1], [measure2], and [measure3].

- Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with [disease name] are followed-up every [duration]. Follow-up testing includes [test 1], [test 2], and [test 3].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E; et al. (2012). "Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition". JAMA. 307 (23): 2526–33. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5669. PMID 22797452.

- ↑ Bernard GR (2005). "Acute respiratory distress syndrome: a historical perspective". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 172 (7): 798–806. doi:10.1164/rccm.200504-663OE. PMC 2718401. PMID 16020801.

- ↑ Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE (1967). "Acute respiratory distress in adults". Lancet. 2 (7511): 319–23. PMID 4143721.

- ↑ Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP (2014). "The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance". Eur Respir J. 43 (1): 276–85. doi:10.1183/09031936.00196412. PMC 4015132. PMID 23520315.

- ↑ Martin C, Papazian L, Payan MJ, Saux P, Gouin F (1995). "Pulmonary fibrosis correlates with outcome in adult respiratory distress syndrome. A study in mechanically ventilated patients". Chest. 107 (1): 196–200. PMID 7813276.

- ↑ Jerng JS, Yu CJ, Wang HC, Chen KY, Cheng SL, Yang PC (2006). "Polymorphism of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene affects the outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome". Crit Care Med. 34 (4): 1001–6. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000206107.92476.39. PMID 16484896.

- ↑ Cardinal-Fernández P, Ferruelo A, El-Assar M, Santiago C, Gómez-Gallego F, Martín-Pellicer A; et al. (2013). "Genetic predisposition to acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with severe sepsis". Shock. 39 (3): 255–60. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182866ff9. PMID 23364437.

- ↑ Tejera P, Meyer NJ, Chen F, Feng R, Zhao Y, O'Mahony DS; et al. (2012). "Distinct and replicable genetic risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome of pulmonary or extrapulmonary origin". J Med Genet. 49 (11): 671–80. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100972. PMC 3654537. PMID 23048207.

- ↑ Pepe PE, Potkin RT, Reus DH, Hudson LD, Carrico CJ (1982). "Clinical predictors of the adult respiratory distress syndrome". Am J Surg. 144 (1): 124–30. PMID 7091520.

- ↑ Lucas AC (1988). "The future of radiological instrumentation". Health Phys. 55 (2): 191–5. PMID 3410685.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Moss M, Mannino DM (2002). "Race and gender differences in acute respiratory distress syndrome deaths in the United States: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data (1979- 1996)". Crit Care Med. 30 (8): 1679–85. PMID 12163776.

- ↑ Heffernan DS, Dossett LA, Lightfoot MA, Fremont RD, Ware LB, Sawyer RG; et al. (2011). "Gender and acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically injured adults: a prospective study". J Trauma. 71 (4): 878–83, discussion 883-5. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31822c0d31. PMC 3201740. PMID 21986736.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Moss M, Bucher B, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE (1996). "The role of chronic alcohol abuse in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults". JAMA. 275 (1): 50–4. PMID 8531287.

- ↑ Moss M, Burnham EL (2003). "Chronic alcohol abuse, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ dysfunction". Crit Care Med. 31 (4 Suppl): S207–12. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000057845.77458.25. PMID 12682442.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Reynolds HN, McCunn M, Borg U, Habashi N, Cottingham C, Bar-Lavi Y (1998). "Acute respiratory distress syndrome: estimated incidence and mortality rate in a 5 million-person population base". Crit Care. 2 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1186/cc121. PMC 28999. PMID 11056707.

- ↑ Sheu CC, Gong MN, Zhai R, Chen F, Bajwa EK, Clardy PF; et al. (2010). "Clinical characteristics and outcomes of sepsis-related vs non-sepsis-related ARDS". Chest. 138 (3): 559–67. doi:10.1378/chest.09-2933. PMC 2940067. PMID 20507948.

- ↑ Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F; et al. (2003). "One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome". N Engl J Med. 348 (8): 683–93. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022450. PMID 12594312.

- ↑ Linko R, Suojaranta-Ylinen R, Karlsson S, Ruokonen E, Varpula T, Pettilä V; et al. (2010). "One-year mortality, quality of life and predicted life-time cost-utility in critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure". Crit Care. 14 (2): R60. doi:10.1186/cc8957. PMC 2887181. PMID 20384998.

- ↑ Wang CY, Calfee CS, Paul DW, Janz DR, May AK, Zhuo H; et al. (2014). "One-year mortality and predictors of death among hospital survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome". Intensive Care Med. 40 (3): 388–96. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-3186-3. PMC 3943651. PMID 24435201.