Abdominal parasitic infection

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mohammed Abdelwahed M.D[2]

|

Abdominal parasitic infection Main page |

Overview

Main parasitic intestinal infections

- Ascaris lumbricoides

- Necator americanus

- Ancylostoma duodenale

- Fasciola

- Schistosoma (S. mansoni, S. haematobium, S. japonicum)

- Trichuris trichiura

- Strongyloides stercoralis

- Taenia (solium, saginatum)

- Hymenolepis nana

- Entamoeba histolytica

- Giardia lamblia

- Entamoeba dispar

- Entamoeba moshkowskii

- Entamoeba coli

- Entamoeba hartmanii

- Endolimax nana

- Iodamoeba butschlii

- Chilomastix mesnili

- Blastocystis hominis

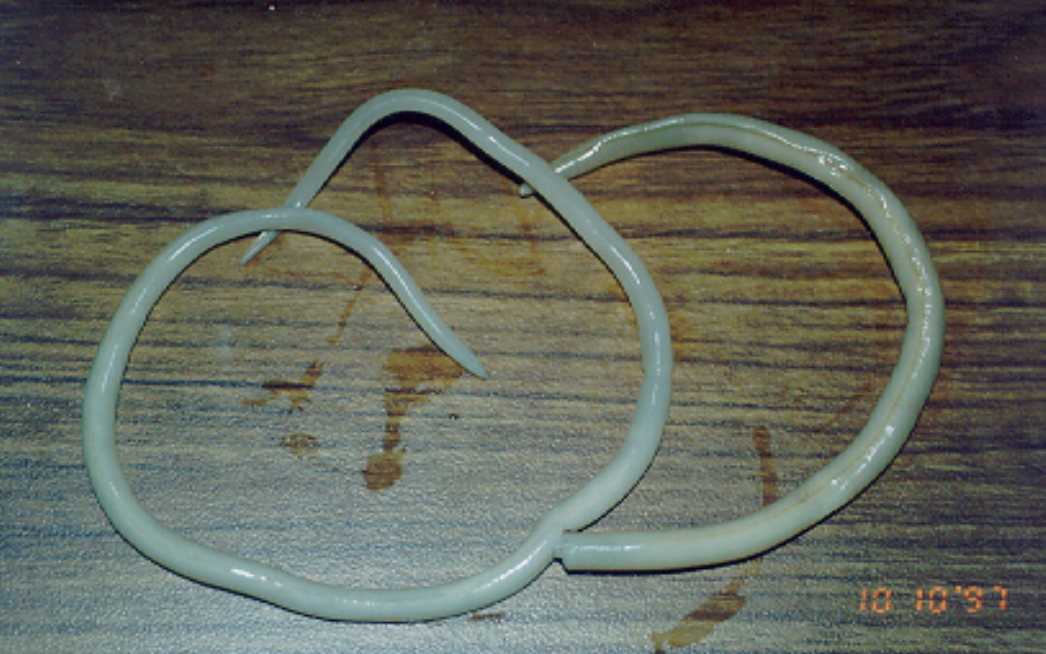

Ascaris lumbricoides

Mode of infection

- Ingestion of eggs secreted in the feces of humans or pigs.

- Ingesting uncooked pig or chicken liver with the larvae.[1]

Epidemiology and demographics

- Approximately 800 million people are infected.[2]

- Majority of individuals infected with ascariasis are in Asia (73 percent), Africa (12 percent), and South America (8 percent).[3]

Clinical manifestations

- During six to eight weeks after egg ingestion, symptoms of ascariasis are abdominal discomfort, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Adult worms may be seen in the stool.

- It is called the late phase of infection.

Complications

- Intestinal obstruction: In endemic areas, 5 to 35 percent of all bowel obstructions are due to ascariasis.[4]

- Approximately 85 percent of obstructions occur in children between one and five years of age.

- Obstruction occurs most commonly at the ileocecal valve.

- Migration of adult Ascaris worms into the biliary tree can cause biliary colic, biliary strictures, acalculous cholecystitis, ascending cholangitis, and bile duct perforation with peritonitis.[5]

Laboratory findings

- Stool microscopy is the most common diagnostic tool for evaluation of Ascaris ova.

- Characteristic eggs may be seen on direct examination of stool.

- Peripheral eosinophilia may be observed.[6]

Imaging findings

- Barium swallow may also demonstrate adult Ascaris worms, which manifest as elongated filling defects of the small bowel making the "bull's eye" appearance.

- Computed tomography scanning or magnetic resonance imaging may demonstrate worms in the bowel or in the liver or bile ducts.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography may detect adult worms in bile or pancreatic ducts.[7]

Treatment

| Drug | Dosage |

| Albendazole | 400 mg orally once |

| Mebendazole | 100 mg orally twice daily for 3 days or 500 mg orally once |

| Ivermectin | 150-200 mcg/kg orally once |

Necator americanus

- Approximetly 800 million people are infected with hookworms worldwide.[8]

- The prevalence of hookworm infection in rural areas of United States in the early 20th century was high.

Acute gastrointestinal symptoms

- Nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, epigastric pain, and increased flatulence may be observed.[9]

- In patients with recurrent infections, gastrointestinal symptoms become less in the proceeding attacks, mild after the second, and absent after the third and fourth infection.

Chronic nutritional impairment

- Hookworms cause blood loss during attachment to the intestinal mucosa by lacerating capillaries and ingesting extravasated blood.[10]

- The daily losses of blood, iron, and albumin can lead to anemia and contribute to impaired nutrition, especially in patients with heavy infection.

- Pregnant females with hookworm infection are associated with low birth weight.

Stool examination

- Stool examination for the eggs of N. americanus or A. duodenale is useful for detection of hookworm infection eight weeks after dermal penetration of N. americanus infection.

- Eosinophilia has been attributed to persistent attachment of adult worms to the intestinal mucosa.[11]

Treatment

- Albendazole is the first line of treatment for hookworms.[12]

- Mebendazole is an alternative therapy; 100 mg twice daily for three days.

- Another alternative therapy is pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg per day for three days, not to exceed 1 g/day).[13]

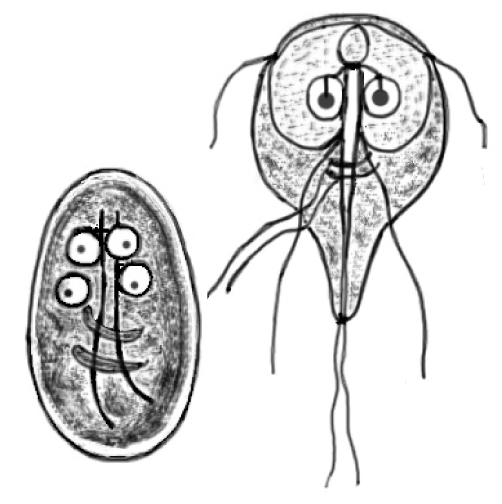

Giardia lamblia

- The prevalence of giardiasis is 20 to 40 percent in endemic areas.

- The highest risk group for infection are children <5 years.[14]

- Approximately, 15,223 cases were reported in the United States in 2012.[15]

- Giardiasis is a major cause of diarrhea among mountains hikers who drink water that has not been boiled.[16]

- Transmission of giardiasis can occur via ingestion of raw or undercooked food contaminated with cysts.[17]

- Giardiasis can be transmitted via anal-oral sexual contact.[18]

Clinical presentation

Asymptomatic infection

- Most of the cases are asymptomatic.[19]

Acute giardiasis

- Symptoms of acute giardiasis include diarrhea, malaise, steatorrhea, abdominal cramps and bloating, nausea, and weight loss.

Chronic giardiasis

- Symptoms of chronic giardiasis may include loose stools, malabsorption, steatorrhea, weight loss, and fatigue.

Complications

- Persistent infection occur in small number of patients causing malabsorption and weight loss.[20]

Laboratory diagnosis

Antigen detection assays

- Fluorescein-tagged monoclonal antibodies, immunochromatographic assays, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are studies using antibodies against cyst or trophozoite antigens. These methods have greater sensitivity.[21]

Nucleic acid amplification assays

- Nucleic acid amplification assays (NAAT) detect Giardia in stool samples.[22]

Stool microscopy

- Stool microscopy to detect Giardia can be specific but needs expert to examine the stool and needs intermittent excretion of Giardia cysts.

Treatment

Preferred agents

- Tinidazole and nitazoxanide are the preferred drug for Giardiasis.[23]

- Tinidazole has a longer half-life than nitazoxanide and may be administered as a single dose with high efficacy (>90 percent).

| Drug | Dose | |

| Adults | Children | |

| Tinidazole | 2 g orally, single dose | Age ≥3 years: 50 mg/kg orally, single dose (maximum dose 2 g) |

| Nitazoxanide | 500 mg orally two times per day for three days | Age 1 to 3 years: 100 mg orally two times per day for 3 days

Age 4 to 11 years: 200 mg orally two times per day for 3 days Age ≥12 years: Same as adult dose |

Fasciola Hepaticum

- Fasciola infection is endemic in Central and South America, Asia (China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, and Thailand), Europe (Portugal, France, Spain, and Turkey), Africa, and the Middle East.

- Children and women are the highest risk groups. It is highly infectious and in some endemic areas to the extent of infecting 100% of the individuals.

Clinical manifestations

- Many infections are mild. Forms of infection include two phases; the acute liver phase and chronic biliary phase.[24]

Acute phase

- The early phase is associated with fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, cough, right upper quadrant pain, hematomas of the liver, jaundice, and hepatomegaly.[25]

- Acute symptoms last for six weeks.

- Complications include focal neurologic changes, pericarditis, arrhythmia, and right-sided pleural effusion.[26]

Chronic phase

- This phase is usually asymptomatic.[27]

- Common bile duct obstruction can develop, and chronic infection can lead to biliary colic, cholangitis, cholelithiasis, and obstructive jaundice.

- Pancreatitis has been reported in 30 percent of cases. Peripheral eosinophilia may disappear.[28]

Complications

- Ascending cholangitis are biliary obstruction may be developed.[29]

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis of fascioliasis should be associated with evaluation of family members.[30]

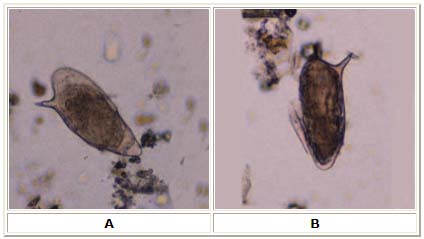

Microscopy

- The diagnosis can be established by identifying eggs in stool, duodenal aspirates, or bile specimens.[31]

- Eggs are not detectable in stool during the acute phase of infection.

- Examination of multiple specimens may be needed or concentration of specimens to facilitate egg identification.[32]

Serology

- It is useful for cases of absent eggs in the stool, early cases and ectopic cases.

- Serologic tests include:

- Indirect hemagglutination

- Complement fixation

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Imaging

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging radiographic findings in fascioliasis are vmultiple small nodules, thickening of the liver capsule, subcapsular hematoma, or parenchymal calcifications or tortuous tracks due to migration of the parasite through the liver.[33]

- Necrotic areas may be seen especially in larger lesions. Peri-portal lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly may be seen, especially in acute fascioliasis.[34]

Treatment

- The treatment of choice is triclabendazole. Dosing consists of 10 mg/kg orally for one or two days. Bithionol and nitazoxanide are alternative choices.[35]

Schistosoma

- The prevalence of schistosomiasis is highest in sub-Saharan Africa.[36]

- Approximately 200 million people are infected annually with 200,000 deaths per year.

Clinical presentation

Acute schistosomiasis syndrome

- Clinical manifestations include sudden onset of fever, urticaria, angioedema, chills, myalgias, arthralgias, dry cough, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and headache.[37]

- The symptoms are usually relatively mild and resolve spontaneously over a period of a few days to a few weeks.[38]

Chronic infection

- Chronic infection related to schistosomiasis is most common among individuals in endemic areas.[39]

Intestinal schistosomiasis

- Intestinal schistosomiasis is caused by infection due to S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. intercalatum, S. mekongi, and, occasionally, S. haematobium.

- The most common symptoms include chronic or intermittent abdominal pain, poor appetite, and diarrhea, bleeding from colonic ulcers that may cause anemia if heavily infested.[40]

- Granulomatous chronic inflammation surrounding eggs in the intestine wall is developed making polyps. Dysplasia is uncommon complication of chronic inflammation.[41]

- Intestinal stricture or obstruction is on the commonest complications.[42]

Hepatosplenic schistosomiasis

- The left liver lobe is enlarged with splenomegy that may extend below the umbilicus. Increased portal hypertension is due to high resistance in the hepatic circulation.[43]

- The predominant pathological process consists of collagen deposition in the periportal spaces causing periportal fibrosis.[44]

- This leads to occlusion of the portal veins, portal hypertension with splenomegaly, portocaval shunting, and gastrointestinal varices.

Pulmonary complications

- Pulmonary manifestations of schistosomiasis occur most frequently among patients with hepatosplenic disease due to chronic infection with S. mansoni, S. japonicum, or S. haematobium.

- Dyspnea is the primary clinical manifestation.[45]

- Chest radiography demonstrates fine miliary nodules.[46]

Genitourinary schistosomiasis

- In early infection, eggs are excreted in the urine and patients present with microscopic or macroscopic hematuria and/or pyuria.[47]

- Blood is usually seen at the end of voiding terminal hematuria, although in severe cases hematuria may be observed for the entire duration of voiding.

- In early chronic infection, the eggs provoke granulomatous inflammation, ulcerations, and development of pseudopolyps in the vesical and ureteral walls, which may be observed on cystoscopy and mimic malignancy.[48]

Laboratory findings

- Eosinophilia is observed in 30 to 60 percent of patients. Eosinophilia is very common among patients with acute schistosomiasis infection.[49]

- Anemia and thrombocytopenia may be observed secondary to splenic sequestration in an enlarged spleen.

- Liver enzymes are near normal even if hepatic fibrosis occurred in most cases.

- Hematuria may occur with S. haematobium infection due to deposition of eggs in the urinary bladder wall.

Microscopy

- Identification of schistosome eggs in a stool or urine sample via microscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis with low sensitivity and high specificity.

Infection intensity

- The intensity of intestinal schistosomiasis is classified as:

- Light: up to 100 eggs per gram

- Moderate: 100 to 400 eggs per gram

- Severe: >400 eggs per gram

- The intensity of urinary schistosomiasis is classified as:

- Light to moderate: up to 50 eggs/10 mL

- Severe: >50 eggs/10 mL

Serology

- Schistosome antigens including extracts of adult worms, cercarial antigens can develop antibodies that may be used in serology test.[50]

- Serology is used as screening mainly because of low sensitivity.

- Serologic tests include:

- Indirect hemagglutination

- Complement fixation

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Molecular tests

- PCR on urine samples noted sensitivity and specificity of 94 and 100 percent, respectively.

- S. mansoni PCR sensitivity is 100 percent and specificity is 90 percent.[51]

Biopsy

- Histopathology of superficial rectal biopsies is more sensitive than stool microscopy and may demonstrate eggs even when multiple stool specimens are negative.[52]

Treatment

- Praziquantel is the drug of choice for schistosomiasis. It increases calcium ion permeability. Calcium ions accumulate in the cytosol, leading to muscular contractions and subsequent paralysis.[53]

- Praziquantel side effects include dizziness, headache, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and pruritus.[54]

- Oxamniquine can be used for refractory schistosomiasis infection and may be as effective as praziquantel.

Strongyloidis Stercoralis

- In tropical and subtropical regions, the prevalence of Strongyloidis Stercoralis infection may exceed 25 percent.[55]

- The highest rates of infection in the United States are among residents of the southeastern states and among individuals who have been in endemic areas.

Gastrointestinal symptoms

The most common manifestations of the hyperinfection syndrome include:[56]

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Anorexia

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Dyspnea

- Wheezing

- Hemoptysis

- Cough

Diagnosis

- Enterotest: Aspiration of duodenojejunal fluid or the use of a string test is sometimes used to detect Strongyloides larvae in patients with negative stool samples.[57]

- Polymerase chain reaction tests have also been developed for detection of Strongyloides in stool samples and have been found to be more sensitive and more reliable in detection of S. stercoralis compared with parasitological methods.

Serology

- ELISA against strongyloides antigens has been proven as useful in diagnosis of immunocompetent individuals.[58]

- ELISA results can be falsely negative in immunocompromised hosts.

Endoscopy

- Upper endoscopy is not usual diagnostic test. Strongyloidiasis has a broad range of endoscopic features:[59]

- In the duodenum, the findings included edema, brown discoloration of the mucosa, erythematous spots, subepithelial hemorrhages, and megaduodenum.

- In the colon, the findings include loss of vascular pattern, edema, aphthous ulcers, erosions, serpiginous ulcerations, and xanthoma-like lesions.

- In the stomach, thickened folds and mucosal erosions are seen.[60]

Treatment

- Ivermectin is the preferred drug for treatment. Administered as two single 200 mcg/kg doses of ivermectin administered on two consecutive days.[61]

Albendazole

- Albendazole (400 mg by mouth on empty stomach twice daily for three to seven days) also has activity against Strongyloides.[62]

E. Histolytica (Amebiasis)

- Areas with high rates of amebic infection include India, Africa, Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. The overall prevalence of amebic infection may be as high as 50 percent in some areas.

- Infection with E. dispar occurs approximately 10 times more frequently than infection with E. histolytica.[63]

Clinical presentation

- The majority of entamoeba infections are asymptomatic; this includes 90 percent of E. histolyticainfections.[64]

- Clinical amebiasis generally has a subacute onset, usually over one to three weeks. Symptoms range from mild diarrhea to severe dysentery, producing abdominal pain (12 to 80 percent), diarrhea (94 to 100 percent), and bloody stools (94 to 100 percent), to fulminant amebic colitis.

- Weight loss occurs in about half of patients, and fever occurs in up to 38 percent.[65]

- Amebic dysentery is diarrhea with visible blood and mucus in stools and the presence of hematophagous trophozoites (trophozoites with ingested red blood cells) in stools or tissues.

- Fulminant colitis with bowel necrosis leading to perforation, and peritonitis has been observed in approximately 0.5 percent of cases; associated mortality rate is more than 40 percent. Toxic megacolon can also develop.

- Amebic colitis has been recognized in asymptomatic patients.[66]

Diagnosis

Stool microscopy

- The demonstration of cysts or trophozoites in the stool suggests intestinal amebiasis, but microscopy cannot differentiate between E. histolytica and E. dispar or E. moshkovskii strains. In addition, microscopy requires specialized expertise and is subject to operator error.[67]

Antigen testing

- Stool and serum antigen detection assays that use monoclonal antibodies to bind to epitopes present on pathogenic E. histolytica strains (but not on nonpathogenic E. dispar strains) are commercially available for diagnosis of E. histolytica infection.[68]

- Antigen detection kits using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), radioimmunoassay, or immunofluorescence have been developed.

- Antigen detection has many advantages, including ease and rapidity of the tests, capacity to differentiate between strains, greater sensitivity than microscopy, and potential for diagnosis in early infection and in endemic areas.

Serology

- Antibodies are detectable within five to seven days of acute infection and may persist for years.

- Approximately 10 to 35 percent of uninfected individuals in endemic areas have antiamebic antibodies due to previous infection with E. histolytica.

- Negative serology is helpful for exclusion of disease, but positive serology cannot distinguish between acute and previous infection.

Molecular methods

- Techniques can detect E. histolytica in stool specimens.

- Studies have shown that PCR is significantly more sensitive than microscopy and that it was 100 percent specific for E. histolytica.[69]

- PCR is about 100 times more sensitive than fecal antigen tests.

Treatment

- All E. histolytica infections should be treated, even in the absence of symptoms, given the potential risk of developing invasive disease and the risk of spread to family members.[70]

- The goals of antibiotic therapy of intestinal amebiasis are to eliminate the invading trophozoites and to eradicate intestinal carriage of the organism.

Taeniasis

Taeniasis

- There are two main species of human Taenia; Taenia saginata, the beef tapeworm, and Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm.[71]

- T. saginata occurs worldwide but is most common in areas where consumption of undercooked beef is customary, such as Europe and parts of Asia.

Clinical presentation

- Most human carriers of adult tapeworms are asymptomatic.

- Symptoms may include nausea, anorexia, or epigastric pain.

- A peripheral eosinophilia (up 15 percent) may be observed.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis is generally established by identifying eggs or proglottids in the stool. The eggs of Taenia species are morphologically indistinguishable.

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of T. solium antigens in fecal samples and DNA hybridization techniques for the detection of eggs in stools can be used in case of failed eggs detection. [11-17].

- Polymerase chain reaction assays targeting various genomic regions have been developed for distinguishing between species of human Taenia infections.

Treatment

- Praziquantel is the treatment of choice for taeniasis.[72]

- Dosing for taeniasis is 5 to 10 mg/kg orally (single dose), although excellent efficacy against T. saginata infections has been reported at doses as low as 2.5 mg/kg.[73]

- Niclosamide is an acceptable alternative treatment for tapeworms if praziquantel is not available. Niclosamide comes in 500 mg tablets that need to be chewed; it is not available in the United States.

Trichuris trichiura

- Trichuris trichiura is a round worm that causes trichuriasis when it infects a human large intestine.

- It is commonly known as the whipworm which refers to the shape of the worm.

Clinical manifestations

- Most infections with T. trichiura are asymptomatic.[74]

- Main symptoms are loose stool which may contain mucus and blood.

- Nocturnal stooling is common. Colitis and dysentery occur most frequently among individuals with >200 worms, and secondary anemia with pica may occur.

- Rectal prolapse can occur in heavily infested patients.

- Children who are heavily infected may have impaired growth and cognition.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of trichuriasis is made by stool examination for eggs.[75]

- Proctoscopy can be performed and frequently demonstrates adult worms protruding from the bowel mucosa.

- Polymerase chain reaction assays targeting various genomic regions are becoming available and are able to detectT. trichiura worms.[76]

- CBC shows peripheral eosinophilia of up to 15 percent and anemia.

Treatment

- Mebendazole is the drug of choice for trichuriasis: 500 mg once daily for three days or 100 mg orally twice daily for three days.[77]

- Albendazole is second-line treatment: 400 mg orally on empty stomach once daily.[78]

Hymenolepis Nana

- Hymenolepis Nana is a species though most common in temperate zones, and is one of the most common cestodes infecting humans, especially children.

- The prevalence of Hymenolepis Nana is higher in warm parts of South Europe, Russia, India, US and Latin America.[79]

- Prevalence is 97% in Moscow children and 34% in Argentina children. It has been reported to affect 4 percent of schoolchildren in rural southeastern United States.

Clinical manifestations

- Most infections are asymptomatic, but symptoms become more common as the parasite burden increases.[80]

- Heavy infections with >1000 worms can occur and are often associated with crampy abdominal pain, diarrhea, anorexia, fatigue, and pruritus ani.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis is generally established by identifying eggs or proglottids in the stool.

- Eggs are 30 to 50 mcm in diameter. They contain an oncosphere and are covered with a thin hyaline outer membrane and a thick inner membrane.

- The sensitivity of stool microscopy can be increased by using concentration techniques such as the FLOTAC method.[81]

- Diagnosis of hymenolepiasis should prompt family screening or empiric treatment, given the potential for person-to-person spread.

Treatment

- Praziquantel is the treatment of choice for hymenolepiasis.[72]

- Dosing for hymenolepiasis is 25 mg/kgorally (single dose), followed by repeat dose 10 days later.[73]

References

- ↑ Permin A, Henningsen E, Murrell KD, Roepstorff A, Nansen P (2000). "Pigs become infected after ingestion of livers and lungs from chickens infected with Ascaris of pig origin". Int J Parasitol. 30 (7): 867–8. PMID 10899534.

- ↑ Betson M, Nejsum P, Bendall RP, Deb RM, Stothard JR (2014). "Molecular epidemiology of ascariasis: a global perspective on the transmission dynamics of Ascaris in people and pigs". J Infect Dis. 210 (6): 932–41. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu193. PMC 4136802. PMID 24688073.

- ↑ Dold C, Holland CV (2011). "Ascaris and ascariasis". Microbes Infect. 13 (7): 632–7. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2010.09.012. PMID 20934531.

- ↑ Khuroo MS (1996). "Ascariasis". Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 25 (3): 553–77. PMID 8863040.

- ↑ Javid G, Wani NA, Gulzar GM, Khan BA, Shah AH, Shah OJ; et al. (1999). "Ascaris-induced liver abscess". World J Surg. 23 (11): 1191–4. PMID 10501884.

- ↑ Weller PF (1992). "Eosinophilia in travelers". Med Clin North Am. 76 (6): 1413–32. PMID 1405826.

- ↑ Reeder MM (1998). "The radiological and ultrasound evaluation of ascariasis of the gastrointestinal, biliary, and respiratory tracts". Semin Roentgenol. 33 (1): 57–78. PMID 9516689.

- ↑ Bradbury RS, Hii SF, Harrington H, Speare R, Traub R (2017). "Ancylostoma ceylanicum Hookworm in the Solomon Islands". Emerg Infect Dis. 23 (2): 252–257. doi:10.3201/eid2302.160822. PMC 5324822. PMID 28098526.

- ↑ Nawalinski TA, Schad GA (1974). "Arrested development in Ancylostoma duodenale: course of a self-induced infection in man". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 23 (5): 895–8. PMID 4451228.

- ↑ Chhabra P, Bhasin DK (2017). "Hookworm-Induced Obscure Overt Gastrointestinal Bleeding". Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15 (11): e161–e162. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.034. PMID 28300694.

- ↑ McKenna ML, McAtee S, Bryan PE, Jeun R, Ward T, Kraus J; et al. (2017). "Human Intestinal Parasite Burden and Poor Sanitation in Rural Alabama". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 97 (5): 1623–1628. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.17-0396. PMID 29016326.

- ↑ Genta RM, Woods KL (1991). "Endoscopic diagnosis of hookworm infection". Gastrointest Endosc. 37 (4): 476–8. PMID 1916173.

- ↑ Serre-Delcor N, Treviño B, Monge B, Salvador F, Torrus D, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B; et al. (2017). "Eosinophilia prevalence and related factors in travel and immigrants of the network +REDIVI". Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 35 (10): 617–623. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2016.02.024. PMID 27032297.

- ↑ Feng Y, Xiao L (2011). "Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis". Clin Microbiol Rev. 24 (1): 110–40. doi:10.1128/CMR.00033-10. PMC 3021202. PMID 21233509.

- ↑ Muhsen K, Levine MM (2012). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between Giardia lamblia and endemic pediatric diarrhea in developing countries". Clin Infect Dis. 55 Suppl 4: S271–93. doi:10.1093/cid/cis762. PMC 3502312. PMID 23169940.

- ↑ Dykes AC, Juranek DD, Lorenz RA, Sinclair S, Jakubowski W, Davies R (1980). "Municipal waterborne giardiasis: an epidemilogic investigation. Beavers implicated as a possible reservoir". Ann Intern Med. 92 (2 Pt 1): 165–70. PMID 7188724.

- ↑ Quick R, Paugh K, Addiss D, Kobayashi J, Baron R (1992). "Restaurant-associated outbreak of giardiasis". J Infect Dis. 166 (3): 673–6. PMID 1500757.

- ↑ Escobedo AA, Almirall P, Alfonso M, Cimerman S, Chacín-Bonilla L (2014). "Sexual transmission of giardiasis: a neglected route of spread?". Acta Trop. 132: 106–11. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.12.025. PMID 24434784.

- ↑ Pickering LK, Woodward WE, DuPont HL, Sullivan P (1984). "Occurrence of Giardia lamblia in children in day care centers". J Pediatr. 104 (4): 522–6. PMID 6707812.

- ↑ Lengerich EJ, Addiss DG, Juranek DD (1994). "Severe giardiasis in the United States". Clin Infect Dis. 18 (5): 760–3. PMID 8075266.

- ↑ Al FD, Kuştimur S, Ozekinci T, Balaban N, Ilhan MN (2006). "The use of enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) methods for diagnosis of Giardia intestinalis". Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 30 (4): 275–8. PMID 17309026.

- ↑ Claas EC, Burnham CA, Mazzulli T, Templeton K, Topin F (2013). "Performance of the xTAG® gastrointestinal pathogen panel, a multiplex molecular assay for simultaneous detection of bacterial, viral, and parasitic causes of infectious gastroenteritis". J Microbiol Biotechnol. 23 (7): 1041–5. PMID 23711521.

- ↑ Fung HB, Doan TL (2005). "Tinidazole: a nitroimidazole antiprotozoal agent". Clin Ther. 27 (12): 1859–84. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.12.012. PMID 16507373.

- ↑ Adachi S, Kotani K, Shimizu T, Tanaka K, Shimizu T, Okada K (2005). "Asymptomatic fascioliasis". Intern Med. 44 (9): 1013–5. PMID 16258225.

- ↑ Chan CW, Lam SK (1987). "Diseases caused by liver flukes and cholangiocarcinoma". Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1 (2): 297–318. PMID 2822181.

- ↑ Arjona R, Riancho JA, Aguado JM, Salesa R, González-Macías J (1995). "Fascioliasis in developed countries: a review of classic and aberrant forms of the disease". Medicine (Baltimore). 74 (1): 13–23. PMID 7837967.

- ↑ Marcos LA, Terashima A, Gotuzzo E (2008). "Update on hepatobiliary flukes: fascioliasis, opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis". Curr Opin Infect Dis. 21 (5): 523–30. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32830f9818. PMID 18725803.

- ↑ Kaya M, Beştaş R, Cetin S (2011). "Clinical presentation and management of Fasciola hepatica infection: single-center experience". World J Gastroenterol. 17 (44): 4899–904. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i44.4899. PMC 3235633. PMID 22171131.

- ↑ Dias LM, Silva R, Viana HL, Palhinhas M, Viana RL (1996). "Biliary fascioliasis: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by ERCP". Gastrointest Endosc. 43 (6): 616–20. PMID 8781945.

- ↑ Kaya M, Beştaş R, Cetin S (2011). "Clinical presentation and management of Fasciola hepatica infection: single-center experience". World J Gastroenterol. 17 (44): 4899–904. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i44.4899. PMC 3235633. PMID 22171131.

- ↑ Prociv P, Walker JC, Whitby M (1992). "Human ectopic fascioliasis in Australia: first case reports". Med J Aust. 156 (5): 349–51. PMID 1588869.

- ↑ Acosta-Ferreira W, Vercelli-Retta J, Falconi LM (1979). "Fasciola hepatica human infection. Histopathological study of sixteen cases". Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 383 (3): 319–27. PMID 158874.

- ↑ Cevikol C, Karaali K, Senol U, Kabaalioğlu A, Apaydin A, Saba R; et al. (2003). "Human fascioliasis: MR imaging findings of hepatic lesions". Eur Radiol. 13 (1): 141–8. doi:10.1007/s00330-002-1470-7. PMID 12541122.

- ↑ Teke M, Önder H, Çiçek M, Hamidi C, Göya C, Çetinçakmak MG; et al. (2014). "Sonographic findings of hepatobiliary fascioliasis accompanied by extrahepatic expansion and ectopic lesions". J Ultrasound Med. 33 (12): 2105–11. doi:10.7863/ultra.33.12.2105. PMID 25425366.

- ↑ Keiser J, Utzinger J (2004). "Chemotherapy for major food-borne trematodes: a review". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 5 (8): 1711–26. doi:10.1517/14656566.5.8.1711. PMID 15264986.

- ↑ Gower CM, Gouvras AN, Lamberton PH, Deol A, Shrivastava J, Mutombo PN; et al. (2013). "Population genetic structure of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium from across six sub-Saharan African countries: implications for epidemiology, evolution and control". Acta Trop. 128 (2): 261–74. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.09.014. PMID 23041540.

- ↑ Rocha MO, Rocha RL, Pedroso ER, Greco DB, Ferreira CS, Lambertucci JR; et al. (1995). "Pulmonary manifestations in the initial phase of schistosomiasis mansoni". Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 37 (4): 311–8. PMID 8599059.

- ↑ Jauréguiberry S, Ansart S, Perez L, Danis M, Bricaire F, Caumes E (2007). "Acute neuroschistosomiasis: two cases associated with cerebral vasculitis". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 76 (5): 964–6. PMID 17488923.

- ↑ Lucey DR, Maguire JH (1993). "Schistosomiasis". Infect Dis Clin North Am. 7 (3): 635–53. PMID 8254164.

- ↑ Stothard JR, Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Betson M, Bustinduy A, Reinhard-Rupp J (2013). "Schistosomiasis in African infants and preschool children: let them now be treated!". Trends Parasitol. 29 (4): 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2013.02.001. PMC 3878762. PMID 23465781.

- ↑ Mu A, Fernandes I, Phillips D (2016). "A 57-Year-Old Woman With a Cecal Mass". Clin Infect Dis. 63 (5): 703–5. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw413. PMID 27521443.

- ↑ Gabbi C, Bertolotti M, Iori R, Rivasi F, Stanzani C, Maurantonio M; et al. (2006). "Acute abdomen associated with schistosomiasis of the appendix". Dig Dis Sci. 51 (1): 215–7. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-3111-5. PMID 16416239.

- ↑ Homeida M, Abdel-Gadir AF, Cheever AW, Bennett JL, Arbab BM, Ibrahium SZ; et al. (1988). "Diagnosis of pathologically confirmed Symmers' periportal fibrosis by ultrasonography: a prospective blinded study". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 38 (1): 86–91. PMID 3124648.

- ↑ Dessein AJ, Hillaire D, Elwali NE, Marquet S, Mohamed-Ali Q, Mirghani A; et al. (1999). "Severe hepatic fibrosis in Schistosoma mansoni infection is controlled by a major locus that is closely linked to the interferon-gamma receptor gene". Am J Hum Genet. 65 (3): 709–21. doi:10.1086/302526. PMC 1377977. PMID 10441577.

- ↑ Sarwat AK, Tag el Din MA, Bassiouni M, Ashmawi SS (1986). "Schistosomiasis of the lung". J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 16 (1): 359–66. PMID 3722898.

- ↑ FARID Z, GREER JW, ISHAK KG, EL-NAGAH AM, LEGOLVAN PC, MOUSA AH (1959). "Chronic pulmonary schistosomiasis". Am Rev Tuberc. 79 (2): 119–33. PMID 13627419.

- ↑ Silva IM, Thiengo R, Conceição MJ, Rey L, Pereira Filho E, Ribeiro PC (2006). "Cystoscopy in the diagnosis and follow-up of urinary schistosomiasis in Brazilian soldiers returning from Mozambique, Africa". Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 48 (1): 39–42. doi:/S0036-46652006000100008 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 16547578. - ↑ Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L (2006). "Human schistosomiasis". Lancet. 368 (9541): 1106–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PMID 16997665.

- ↑ Mahmoud AA (1982). "The ecology of eosinophils in schistosomiasis". J Infect Dis. 145 (5): 613–22. PMID 7042854.

- ↑ Tsang VC, Wilkins PP (1991). "Immunodiagnosis of schistosomiasis. Screen with FAST-ELISA and confirm with immunoblot". Clin Lab Med. 11 (4): 1029–39. PMID 1802520.

- ↑ Webster BL, Rollinson D, Stothard JR, Huyse T (2010). "Rapid diagnostic multiplex PCR (RD-PCR) to discriminate Schistosoma haematobium and S. bovis". J Helminthol. 84 (1): 107–14. doi:10.1017/S0022149X09990447. PMID 19646307.

- ↑ Harries AD, Fryatt R, Walker J, Chiodini PL, Bryceson AD (1986). "Schistosomiasis in expatriates returning to Britain from the tropics: a controlled study". Lancet. 1 (8472): 86–8. PMID 2867326.

- ↑ Cioli D, Pica-Mattoccia L, Basso A, Guidi A (2014). "Schistosomiasis control: praziquantel forever?". Mol Biochem Parasitol. 195 (1): 23–9. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.06.002. PMID 24955523.

- ↑ Araújo N, Kohn A, Katz N (1991). "Activity of the artemether in experimental schistosomiasis mansoni". Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 86 Suppl 2: 185–8. PMID 1841998.

- ↑ Jourdan PM, Lamberton PHL, Fenwick A, Addiss DG (2017). "Soil-transmitted helminth infections". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31930-X. PMID 28882382.

- ↑ Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ (1978). "Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection". Medicine (Baltimore). 57 (6): 527–44. PMID 362122.

- ↑ Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Walker PF (2008). "Hypereosinophilic syndrome and mepolizumab". N Engl J Med. 358 (26): 2839, author reply 2839-40. PMC 2596663. PMID 18589879.

- ↑ Carroll SM, Karthigasu KT, Grove DI (1981). "Serodiagnosis of human strongyloidiasis by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 75 (5): 706–9. PMID 7036430.

- ↑ Sreenivas DV, Kumar A, Kumar YR, Bharavi C, Sundaram C, Gayathri K (1997). "Intestinal strongyloidiasis--a rare opportunistic infection". Indian J Gastroenterol. 16 (3): 105–6. PMID 9248183.

- ↑ Qu Z, Kundu UR, Abadeer RA, Wanger A (2009). "Strongyloides colitis is a lethal mimic of ulcerative colitis: the key morphologic differential diagnosis". Hum Pathol. 40 (4): 572–7. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.10.008. PMID 19144377.

- ↑ Zaha O, Hirata T, Kinjo F, Saito A, Fukuhara H (2002). "Efficacy of ivermectin for chronic strongyloidiasis: two single doses given 2 weeks apart". J Infect Chemother. 8 (1): 94–8. doi:10.1007/s101560200013. PMID 11957127.

- ↑ Archibald LK, Beeching NJ, Gill GV, Bailey JW, Bell DR (1993). "Albendazole is effective treatment for chronic strongyloidiasis". Q J Med. 86 (3): 191–5. PMID 8483992.

- ↑ Weinke T, Friedrich-Jänicke B, Hopp P, Janitschke K (1990). "Prevalence and clinical importance of Entamoeba histolytica in two high-risk groups: travelers returning from the tropics and male homosexuals". J Infect Dis. 161 (5): 1029–31. PMID 2324531.

- ↑ Ximénez C, Cerritos R, Rojas L, Dolabella S, Morán P, Shibayama M; et al. (2010). "Human amebiasis: breaking the paradigm?". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 7 (3): 1105–20. doi:10.3390/ijerph7031105. PMC 2872301. PMID 20617021.

- ↑ Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG (2009). "Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006085. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub2. PMID 19370624.

- ↑ Misra SP, Misra V, Dwivedi M (2006). "Ileocecal masses in patients with amebic liver abscess: etiology and management". World J Gastroenterol. 12 (12): 1933–6. PMC 4087520. PMID 16610001.

- ↑ Rayan HZ (2005). "Microscopic overdiagnosis of intestinal amoebiasis". J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 35 (3): 941–51. PMID 16333901.

- ↑ González-Ruíz A, Haque R, Rehman T, Aguirre A, Castañón G, Hall A; et al. (1992). "Further diagnostic use of an invasive-specific monoclonal antibody against Entamoeba histolytica". Arch Med Res. 23 (2): 281–3. PMID 1340315.

- ↑ Rayan HZ (2005). "Microscopic overdiagnosis of intestinal amoebiasis". J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 35 (3): 941–51. PMID 16333901.

- ↑ Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA (2003). "Amebiasis". N Engl J Med. 348 (16): 1565–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMra022710. PMID 12700377.

- ↑ Forrester JE, Bailar JC, Esrey SA, José MV, Castillejos BT, Ocampo G (1998). "Randomised trial of albendazole and pyrantel in symptomless trichuriasis in children". Lancet. 352 (9134): 1103–8. PMID 9798586.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Ohnishi K, Sakamoto N, Kobayashi K, Iwabuchi S, Nakamura-Uchiyama F (2013). "Therapeutic effect of praziquantel against Taeniasis asiatica". Int J Infect Dis. 17 (8): e656–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.02.028. PMID 23618773.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Pawłowski ZS (1990). "Efficacy of low doses of praziquantel in taeniasis". Acta Trop. 48 (2): 83–8. PMID 1980572.

- ↑ Forrester JE, Bailar JC, Esrey SA, José MV, Castillejos BT, Ocampo G (1998). "Randomised trial of albendazole and pyrantel in symptomless trichuriasis in children". Lancet. 352 (9134): 1103–8. PMID 9798586.

- ↑ Forrester JE, Bailar JC, Esrey SA, José MV, Castillejos BT, Ocampo G (1998). "Randomised trial of albendazole and pyrantel in symptomless trichuriasis in children". Lancet. 352 (9134): 1103–8. PMID 9798586.

- ↑ Phuphisut O, Yoonuan T, Sanguankiat S, Chaisiri K, Maipanich W, Pubampen S; et al. (2014). "Triplex polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of major soil-transmitted helminths, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus, in fecal samples". Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 45 (2): 267–75. PMID 24968666.

- ↑ Rossignol JF, Maisonneuve H (1984). "Benzimidazoles in the treatment of trichuriasis: a review". Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 78 (2): 135–44. PMID 6378109.

- ↑ Steinmann P, Utzinger J, Du ZW, Jiang JY, Chen JX, Hattendorf J; et al. (2011). "Efficacy of single-dose and triple-dose albendazole and mebendazole against soil-transmitted helminths and Taenia spp.: a randomized controlled trial". PLoS One. 6 (9): e25003. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025003. PMC 3181256. PMID 21980373.

- ↑ Utzinger J, Botero-Kleiven S, Castelli F, Chiodini PL, Edwards H, Köhler N; et al. (2010). "Microscopic diagnosis of sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin-fixed stool samples for helminths and intestinal protozoa: a comparison among European reference laboratories". Clin Microbiol Infect. 16 (3): 267–73. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02782.x. PMID 19456836.

- ↑ Muehlenbachs A, Bhatnagar J, Agudelo CA, Hidron A, Eberhard ML, Mathison BA; et al. (2015). "Malignant Transformation of Hymenolepis nana in a Human Host". N Engl J Med. 373 (19): 1845–52. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1505892. PMID 26535513.

- ↑ Steinmann P, Cringoli G, Bruschi F, Matthys B, Lohourignon LK, Castagna B; et al. (2012). "FLOTAC for the diagnosis of Hymenolepis spp. infection: proof-of-concept and comparing diagnostic accuracy with other methods". Parasitol Res. 111 (2): 749–54. doi:10.1007/s00436-012-2895-9. PMID 22461006.