Villous adenoma

|

Villous adenoma Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Villous adenoma On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Villous adenoma |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Jogeet Singh Sekhon, M.D. [2] Maria Fernanda Villarreal, M.D. [3]

Synonyms and keywords: Adenomatous polyps; VA; TVA

Overview

Villous adenoma (also known as adenomatous polyp) is a type of polyp that grows in the gastrointestinal tract; it occurs most commonly in the colon. Villous adenoma may result in malignanttransformation. Villous adenoma was first discovered by Helwig in 1946. Villous adenoma may be classified into flat, sessile, pedunculated and depressed subtypes. Villous adenoma arises from epithelial tissue, which is normally part of the lining of the colon. Genes associated with the development of villous adenoma include APC, TP53, K-ras, STK11 and SMAD4. The prevalence of villous adenoma is approximately 3.5 per 100,000 individuals worldwide. The most potent risk factors in the development of villous adenoma include familial syndromes such as Turcot syndrome, juvenile polyposis syndrome, and Cowden disease. Surgical removal is the mainstay of therapy for villous adenoma. Exploratory colonoscopy and cautery snare is the most common approach to the diagnosis and treatment of villous adenoma. Effective measures for the primary prevention of villous adenoma include periodic screening of patients with family history of familial adenomatous polyposis. Secondary prevention strategies include annual occult blood test and colonoscopy.

Historical Perspective

Villous adenoma was first discovered by Helwig in 1946.[1]

Classification

Colon polyps are classified into 3 subtypes according to their histological appearance:[2]

Villous adenoma is classified into 4 types according to the gross appearance:[3]

- Flat

- Sessile

- Pedunculated

- Depressed

Villous adenoma is classified into 2 types according to dysplasia:

- Low grade dysplasia

- High grade dysplasia

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- Villous adenoma is a type of colon polyp.[4][3][5][6]

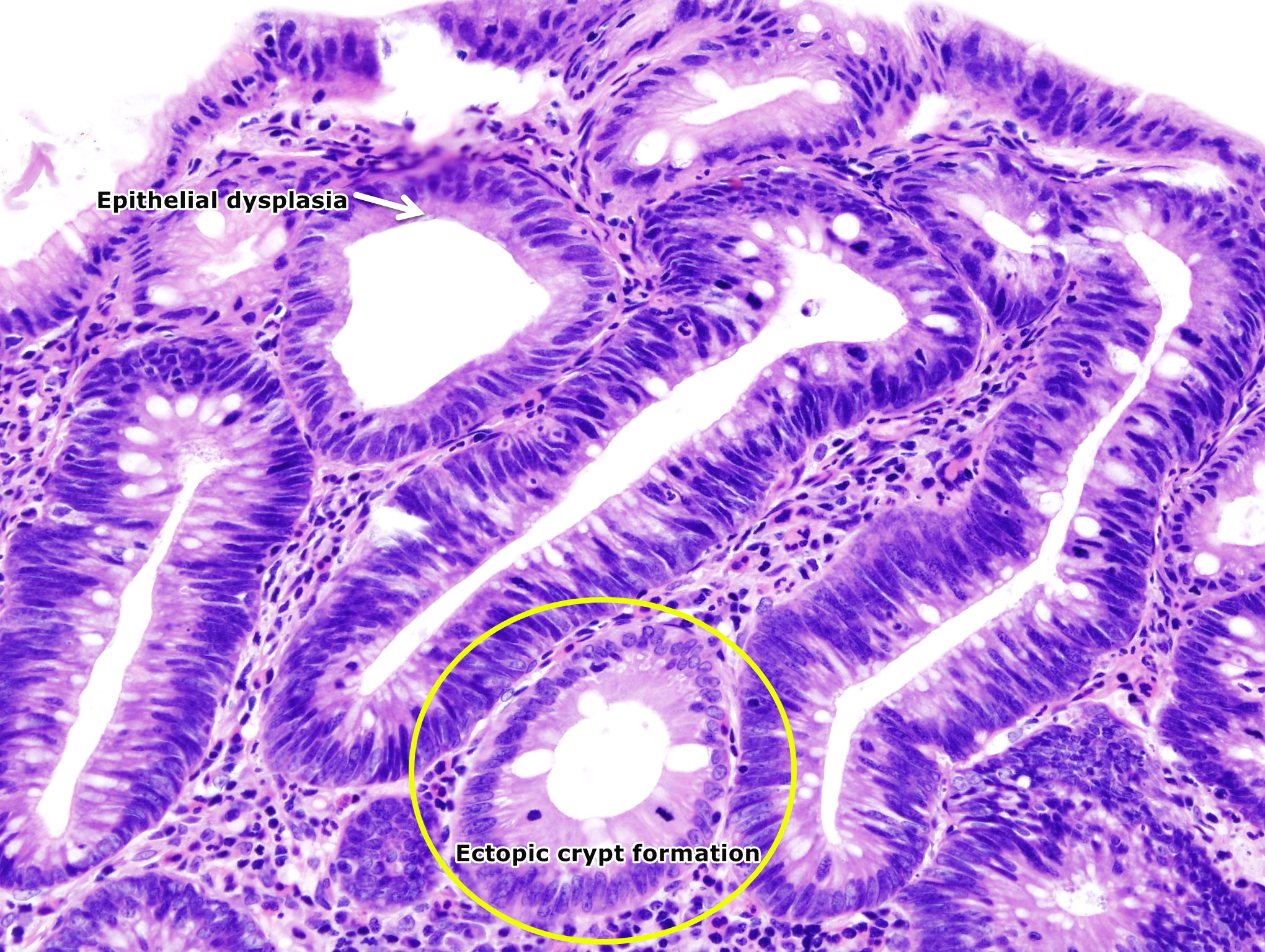

- The pathogenesis of villous adenoma is characterized by overgrowth of epithelial tissue with glandular characteristics.[2][7]

- Dysplastic changes are present in the adenomas.

- Multiple genetic mutations result in the transition from normal mucosa to adenoma to severe dysplasia and finally to carcinoma.

- Low grade or high-grade dysplasia, which indicates the level of maturation of the epithelium determine the progression of the adenoma.

- Features of low grade dysplasia are:

- The cytological features include crowded, pseudo-stratification to early stratification of spindled or elongated nuclei which occupy the basal half of the cytoplasm.[8]

- Pleomorphism and atypical mitoses are absent.

- The crypts maintain a resemblance to normal colon, without significant crowding, cribriform, or complex forms.The lesions are confined to the epithelial layer of crypts and lack invasion through the basement membrane into the lamina propria.

- As there are no lymphatic vessels in the lamina propria, lesions with low grade dysplasia are not associated with metastasis.

- Features of high grade dysplasia are:

- The cytological features include increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, more significant loss of polarity and nuclei with increasingly prominent nucleoli.

- Significant pleomorphism, rounded nuclei, atypical mitoses, and significant loss of polarity.

- The crypts are cribriform and crowded with back-to-back glandular tissue [9].

- These adenomas have a significant risk of metastasis as the lesions can invade into the lamina propria through basement membrane destruction.

- Villous adenoma can lead to adenocarcinoma of the colon.

- The progression of adenoma-to-carcinoma is dependent on the activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes.[10]

- Multiple genetic mutations result in the transition from normal mucosa to adenoma to severe dysplasia and finally to carcinoma.

- The genes involved in adenoma formation are:

- K-ras oncogene

- Tumor suppressor p53 gene

- APC gene on chromosome 5 associated with familial automatosis polyposis syndrome and Gardner's syndrome

- STK11 (LBK1) gene, located on chromosome 19 associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- SMAD4 on chromosome 8 associated with juvenile polyposis syndrome

- Villous adenomas may cause secretory diarrhea characterized by hypokalemia, chloride-rich stool, and metabolic alkalosis. Increased numbers of goblet cells and increased prostaglandin E2 are responsible for the diarrhea.

Causes

The cause of villous adenoma is not yet identified.

Differentiating Villous Adenoma from Other Diseases

Villous adenoma must be differentiated from other diseases that cause abnormal growth of tissue projecting from a mucous membrane such as:

- Colorectal cancer

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp

- Tubular adenoma

- Tubulovillous adenoma

- Hyperplastic polyp

Epidemiology and Demographics

Prevalence

- The prevalence of villous adenoma is approximately 3.5 per 100,000 individuals worldwide.[11]

Age

- Patients of all age groups may develop villous adenoma but the risk increases with age.

Gender

- Males are more commonly affected with villous adenoma than females.

Race

- African Americans are more prone to develop villous adenoma.

Region

- Villous adenomas is common worldwide and has no regional predilection.

Risk Factors

Common risk factors in the development of villous adenoma include[12][13]:

- Age more than 50 years

- African American race

- Male sex

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Alcohol abuse

- Obesity

- Lack of exercise

- Diet high in red meats and processed meats

- Low fiber intake

- Low calcium intake

- Low folate intake

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Familial adenomatous polyposis

- Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

- Turcot syndrome

- Juvenile polyposis syndrome

- Cowden disease

- Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome (Bannayan-Zonana syndrome)

- Gardner's syndrome

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

- The majority of patients with villous adenoma remain asymptomatic for years.[14]

- They are usually found accidentally on routine colonoscopic surveillance.

- Early clinical features may include flatulence, bloating, and abdominal pain.

- If left untreated, patients with villous adenoma may progress to develop colorectal cancer.[2]

- The patients may have a previous history of colon polyps.

- Family history of colon cancer or colon polyps.

Complications

Common complications of villous adenoma include:

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Intestinal obstruction

- Progression to colorectal cancer

Prognosis

- The prognosis of villous adenoma is generally good and the 5-year mortality is approximately 89%.[15]

- Prognosis becomes poor with malignant transformation of the lesion.

- Multiple villous adenomas may suggest genetic disorders and prognosis is poor in these cases.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic study of choice

- Biopsy of the lesion is the diagnostic study of choice[3].

- Villous adenoma is detected on colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy.

History and Symptoms

Villous adenoma is commonly asymptomatic but sometimes patients may present with the following symptoms:[16][3]

- Flatulence

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Cramping

- Blood in stools

- Weight loss

- Change in bowel habits

- Fatigue

Physical Examination

Patients with villous adenoma usually appear well but may have the following signs on examination.

- Pallor due to occult bleeding

- Abdominal tenderness

- Bright red blood on digital rectal examination

- Rectal mass on digital rectal examination

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings associated with villous adenoma are:

- Positive fecal occult blood test

- Hypokalemia[17]

- Anemia

Electrocardiogram

X-ray

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

CT scan

MRI

Other Imaging Findings

Other Diagnostic Studies

On colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy, villous adenoma is visualised as a polyp.

Alternative imaging studies include:

- CT colonography

- Video capsule endoscopy

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- There is no medical therapy for villous adenoma.

- Surgical removal of the adenoma is the mainstay of treatment.

- However, aspirin 75mg PO per day is recommended to prevent recurrence of the adenoma and progression to colorectal cancer.[18]

Surgery

- Surgical removal is the mainstay of therapy for villous adenoma.[19][20]

- The removal of adenoma is known as polypectomy and is done through colonoscopy by endoscopic forceps snare.

- The removed adenoma must be sent for biopsy.

{{#ev:youtube|ClgRkyhaJZw}}

Primary Prevention

Effective measures for the primary prevention of villous adenoma include:

- Periodic screening for polyps in patients with family history of :

- Exercise

- Smoking cessation

- Avoid alcohol

- High fiber diet

Secondary Prevention

Aspirin 75mg PO daily.

- Annual fecal occult blood test[21]

- Colonoscopy every ten years for patients above the age of 50 with no family history of colon cancer or no history of colon polyps

- Colonoscopy at the age of 40 or 10 years before the age of cancer diagnosis in a relative with colon cancer and repeat every 3-5 years

- Colonoscopy after polypectomy:

- Every 5 years if 1-2 adenomas present or size <1 cm

- Every 3 years if 3-10 adenomas present or when size of adenoma is 1-2 cm

- Every 1-2 years if >10 adenomas present or if size is >2cm

- Every 2-6 months if signs of adenocarcinoma present

References

- ↑ Helwig E.B. Adenoma of the large bowel in children. . American Journal of Diseases in Children. 1946;72:289–95

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Osifo OD, Akhiwu W, Efobi CA (2009). "Small intestinal tubulovillous adenoma--case report and literature review". Niger J Clin Pract. 12 (2): 205–7. PMID 19764676.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Shussman, N.; Wexner, S. D. (2014). "Colorectal polyps and polyposis syndromes". Gastroenterology Report. 2 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1093/gastro/got041. ISSN 2052-0034.

- ↑ Rüschoff J, Aust D, Hartmann A (2007). "[Colorectal serrated adenoma: diagnostic criteria and clinical implications]". Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol (in German). 91: 119–25. PMID 18314605.

- ↑ Singh, Rajvinder; Zorrón Cheng Tao Pu, Leonardo; Koay, Doreen; Burt, Alastair (2016). "Sessile serrated adenoma/polyps: Where are we at in 2016?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (34): 7754. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7754. ISSN 1007-9327.

- ↑ Kahi, Charles J.; Vemulapalli, Krishna C.; Snover, Dale C.; Abdel Jawad, Khaled H.; Cummings, Oscar W.; Rex, Douglas K. (2015). "Findings in the Distal Colorectum Are Not Associated With Proximal Advanced Serrated Lesions". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 13 (2): 345–351. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.044. ISSN 1542-3565.

- ↑ "StatPearls". 2018. PMID 29262150.

- ↑ Costantini M, Sciallero S, Giannini A, Gatteschi B, Rinaldi P, Lanzanova G; et al. (2003). "Interobserver agreement in the histologic diagnosis of colorectal polyps. the experience of the multicenter adenoma colorectal study (SMAC)". J Clin Epidemiol. 56 (3): 209–14. PMID 12725874.

- ↑ Rubio CA (2018). "Preliminary Report: Multiple Clusters of Proliferating Cells in Non-dysplastic Corrupted Colonic Crypts Underneath Conventional Adenomas". In Vivo. 32 (6): 1473–1475. doi:10.21873/invivo.11401. PMID 30348703.

- ↑ Komuta K, Batts K, Jessurun J, Snover D, Garcia-Aguilar J, Rothenberger D; et al. (2004). "Interobserver variability in the pathological assessment of malignant colorectal polyps". Br J Surg. 91 (11): 1479–84. doi:10.1002/bjs.4588. PMID 15386327.

- ↑ Giacosa A, Frascio F, Munizzi F (2004). "Epidemiology of colorectal polyps". Tech Coloproctol. 8 Suppl 2: s243–7. doi:10.1007/s10151-004-0169-y. PMID 15666099.

- ↑ Jin Y, Yao L, Zhou P, Jin S, Wang X, Tang X; et al. (2018). "[Risk analysis of the canceration of colorectal large polyps]". Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 21 (10): 1161–1166. PMID 30370516.

- ↑ Morimoto LM, Newcomb PA, Ulrich CM, Bostick RM, Lais CJ, Potter JD (2002). "Risk factors for hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps: evidence for malignant potential?". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 11 (10 Pt 1): 1012–8. PMID 12376501.

- ↑ Bonnington, Stewart N (2016). "Surveillance of colonic polyps: Are we getting it right?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (6): 1925. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i6.1925. ISSN 1007-9327.

- ↑ Bettington, Mark; Walker, Neal; Clouston, Andrew; Brown, Ian; Leggett, Barbara; Whitehall, Vicki (2013). "The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges". Histopathology. 62 (3): 367–386. doi:10.1111/his.12055. ISSN 0309-0167.

- ↑ Johnson, David H.; Kisiel, John B.; Burger, Kelli N.; Mahoney, Douglas W.; Devens, Mary E.; Ahlquist, David A.; Sweetser, Seth (2017). "Multitarget stool DNA test: clinical performance and impact on yield and quality of colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 85 (3): 657–665.e1. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.11.012. ISSN 0016-5107.

- ↑ Villous adenoma. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villous_adenoma Accessed on May 3, 2016

- ↑ Dehmer SP, Maciosek MV, Flottemesch TJ, LaFrance AB, Whitlock EP (2016). "Aspirin for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Colorectal Cancer: A Decision Analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Ann. Intern. Med. 164 (12): 777–86. doi:10.7326/M15-2129. PMID 27064573.

- ↑ Winawer, Sidney J. (2015). "The History of Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Personal Perspective". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 60 (3): 596–608. doi:10.1007/s10620-014-3466-y. ISSN 0163-2116.

- ↑ Rameshshanker, R.; Wilson, Ana (2016). "Electronic Imaging in Colonoscopy: Clinical Applications and Future Prospects". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 14 (1): 140–151. doi:10.1007/s11938-016-0075-1. ISSN 1092-8472.

- ↑ Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR (2012). "Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". Gastroenterology. 143 (3): 844–857. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. PMID 22763141.