Bile duct cyst: Difference between revisions

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

==[[Bile duct cyst epidemiology and demographics|Epidemiology and Demographics]]== | ==[[Bile duct cyst epidemiology and demographics|Epidemiology and Demographics]]== | ||

In the western population 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 150,000 people are thought to have biliary cysts. Up to 1:1000 is the incidence rate in various Asian nations, with Japan accounting for between 50% and 66.6%of all documented cases. According to a survey from Finland, biliary cyst incidence has increased from 1:128,000 to 1:38,000 during the past 40 years. The female to male ratio is between 3:1 and 4:1. Although some reports suggest equal numbers in children and adults but most of the cases have been seen in children. | |||

==[[Bile duct cyst risk factors|Risk Factors]]== | ==[[Bile duct cyst risk factors|Risk Factors]]== | ||

Revision as of 12:56, 30 July 2022

For patient information click here

| Bile duct cyst | |

| |

|---|---|

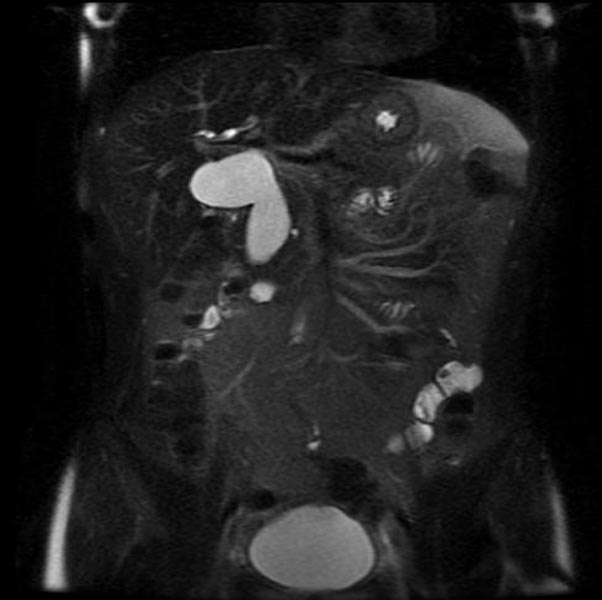

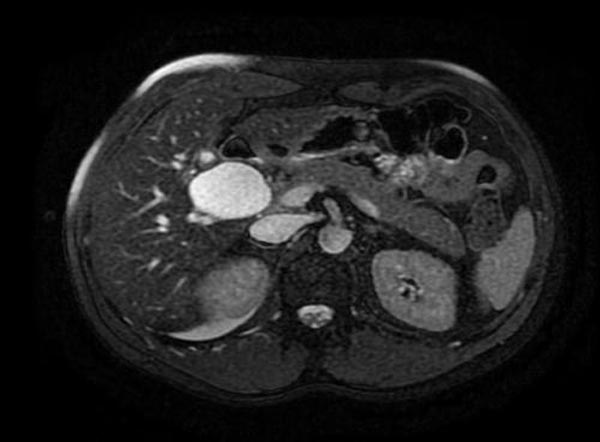

| MRCP: Type 4 bile duct cyst. Image courtesy of RadsWiki |

|

Bile duct cyst Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Bile duct cyst On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Bile duct cyst |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Synonyms and keywords: Choledochal cysts

Overview

Historical Perspective

Vachel and Stevens were the first to describe a case of cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts in 1906, but Jacques Caroli in 1958 gave a more thorough description of a syndrome of congenital malformation of the intrahepatic ducts with segmental cystic dilatation, increased biliary lithiasis, cholangitis and liver abscesses, associated with renal cystic disease or tubular ectasia. The disease is uncommon, with about 180 cases reported in the literature.

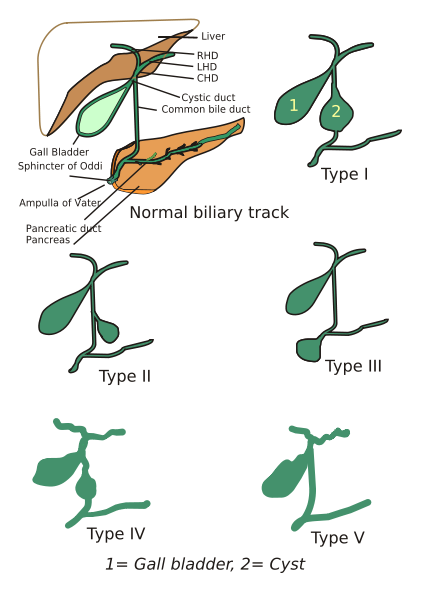

Classification

According to the Todani system, there are five types of bile duct cysts.[1]. This classification was based on site of the cyst or dilatation. Type I to IV has been subtyped.

Type 1: Choledochal Cyst

Choledochal cysts are cystic dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD). Most common variety involving saccular or fusiform dilatation of a portion or entire common bile duct (CBD) with normal intrahepatic duct.

- Account for 80% to 90% of all bile duct cysts

- Often presents during infancy with significant liver disease.

- Characterized by fusiform dilation of the extrahepatic bile duct

- Theorized that choledochal cysts form as the result of reflux of pancreatic secretions into the bile duct via anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction.

- Cyst should be resected completely to prevent associated complications (i.e. ascending cholangitis and malignant transformation).

Type 2: Diverticulum

Isolated diverticulum protruding from the CBD.

- Accounts for 3% of all bile duct cysts

- Represents a true diverticulum.

- Saccular outpouchings arising from the supraduodenal extrahepatic bile duct or the intrahepatic bile ducts.

Type 3: Choledochocele[3]

Arise from dilatation of duodenal portion of CBD or where pancreatic duct meets.

- Accounts for 5% of all bile duct cysts

- Represents protrusion of a focally dilated, intramural segment of the distal common bile duct into the duodenum.

- Choledochoceles may be successfully managed with endoscopic sphincterotomy, surgical excision, or both, in symptomatic patients.

- Often present with pain and obstructive jaundice; many have pancreatitis.

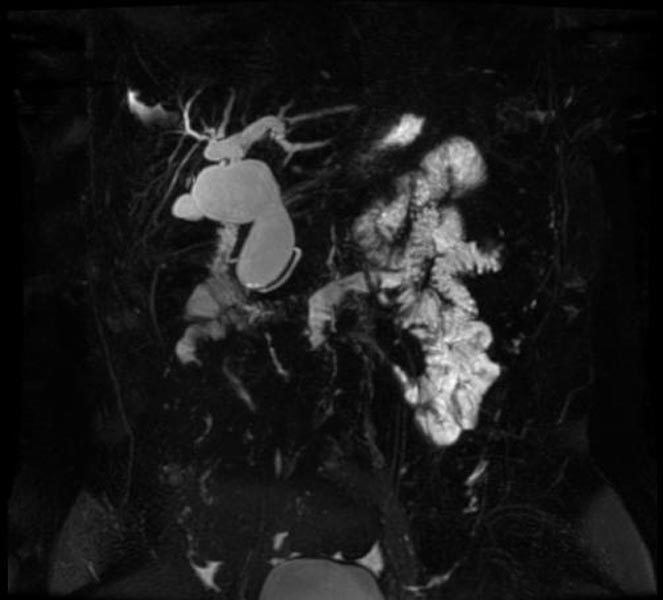

Type 4: Multiple Communicating Intra and Extrahepatic Duct Cysts

Dilatation of both intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary duct.

- Second most common type of bile duct cysts (10%)

- Subdivided into subtypes A and B.

- Type 4A: Fusiform dilation of the entire extrahepatic bile duct with extension of dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts

- Type 4B: Multiple cystic dilations involving only the extrahepatic bile duct.

-

MRI - T2: Type 4 bile duct cyst

-

MRI - T2: Type 4 bile duct cyst

-

MRI - T2: Type 4 bile duct cyst

-

MRCP: Type 4 bile duct cyst

Type 5: Caroli's Disease

Cystic dilatation of intra hepatic biliary ducts. [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

- Caroli's disease is a rare form of congenital biliary cystic disease manifested by cystic dilations of intrahepatic bile ducts

- Association with benign renal tubular ectasia and other forms of renal cystic disease.

Type 6

- Rare Disease

- Isolated cystic duct dilatations

Pathophysiology

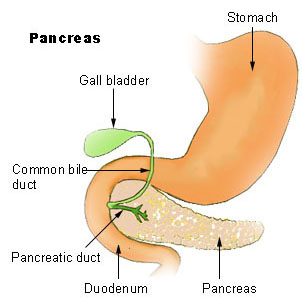

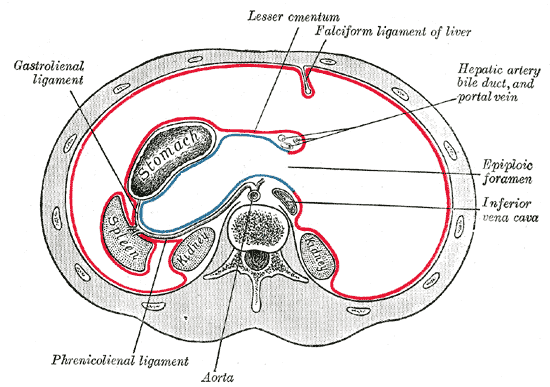

Bile Duct Anatomy

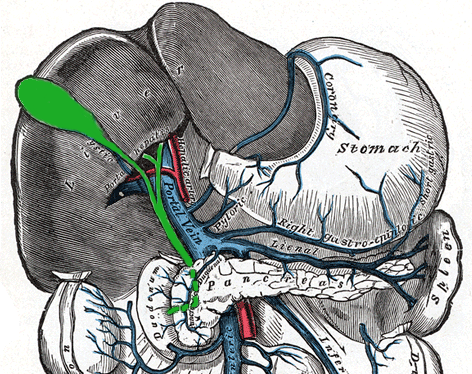

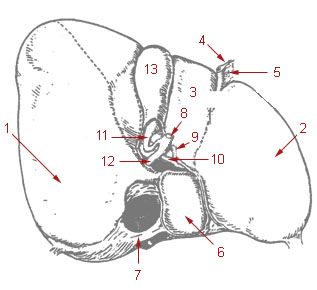

The path is as follows: Bile canaliculi → Canals of Hering → interlobular bile ducts → intrahepatic bile ducts → left and right hepatic ducts merge to form → common hepatic duct exits liver and joins → cystic duct (from gall bladder) forming → common bile duct → joins with pancreatic duct → forming ampulla of Vater → enters duodenum

-

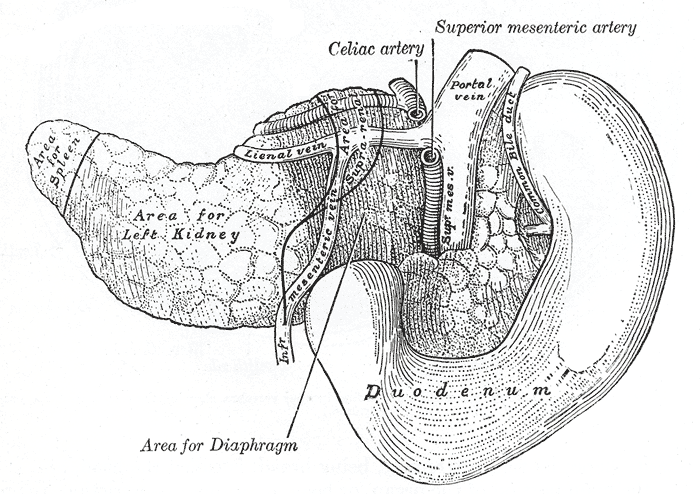

Region of pancreas

-

The celiac ganglia with the sympathetic plexuses of the abdominal viscera radiating from the ganglia.

-

Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the upper part of the abdomen.

-

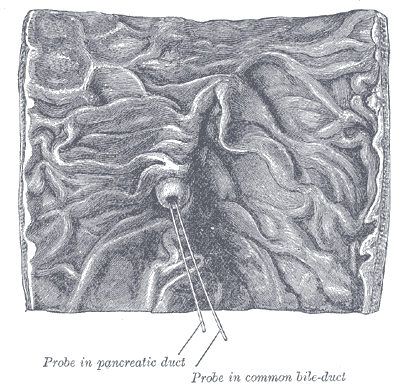

Interior of the descending portion of the duodenum, showing bile papilla.

-

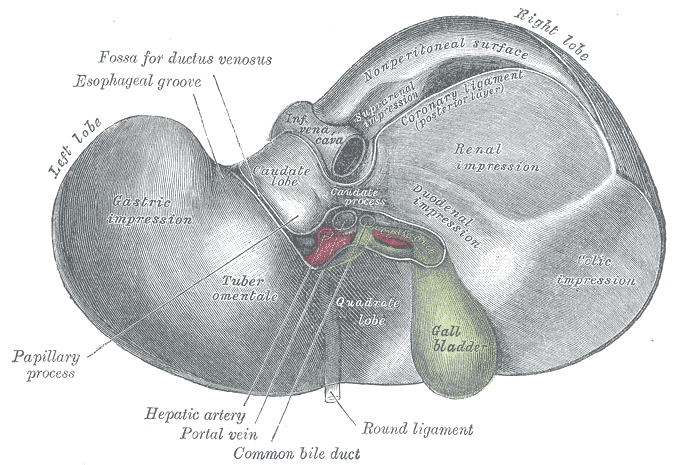

Inferior surface of the liver.

-

The pancreas and duodenum from behind.

-

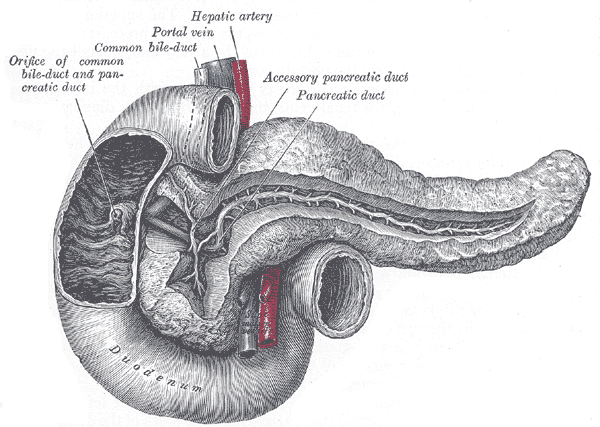

The pancreatic duct.

-

The portal vein and its tributaries.

-

Liver and gallbladder

Causes

Many biliary cysts are congenitally acquired, perhaps as a consequence of the unequal proliferation of epithelial cells during embryonic biliary duct development. Some biliary cysts are acquired, and some may develop in association with anatomic variations that lead to abnormally high ductal pressures in association with other predisposing factors.

Differentiating Bile Duct Cyst from other Diseases

Epidemiology and Demographics

In the western population 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 150,000 people are thought to have biliary cysts. Up to 1:1000 is the incidence rate in various Asian nations, with Japan accounting for between 50% and 66.6%of all documented cases. According to a survey from Finland, biliary cyst incidence has increased from 1:128,000 to 1:38,000 during the past 40 years. The female to male ratio is between 3:1 and 4:1. Although some reports suggest equal numbers in children and adults but most of the cases have been seen in children.

Risk Factors

Screening

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Diagnosis

History, and Symptoms | Physical Examination |

Laboratory Findings

The laboratory tests are not specific and may show slightly abnormal liver function and cholestasis tests (serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase) and amylase values.[9][10]

Ultrasound |

The first and most basic test is the USG. The diameter of the common bile duct, common hepatic duct, and BC can be measured, allowing imaging of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. It reveals a cystic mass in the right upper quadrant (often near the porta hepatis) that is distinct from the gallbladder (except for type-III and type-V cysts).

USG in prenatal diagnosis of Biliary cyst

It shows a spherical intra-abdominal cystic mass in the upper abdominal quadrant. According to the color Doppler USG, There is no discernible flow within the mass. It's essential to make an accurate early differential diagnosis between BC and other biliary diseases. The most important is BA(Biliary atresia) which is a surgical emergency. To distinguish between these two disorders, Tanaka et al. evaluated imaging (USG and CT) and laboratory tests in BC and BA. They came to the conclusion that patients who had biliary disorders smaller than 21 mm, total bile acid levels greater than 111 mol/L, and direct bilirubin levels greater than 2.5 mg/dL, in the neonatal period were more likely to have BA than BC and required emergent surgery to prevent irreversible liver cirrhosis.

Okada et al. by using an immunohistological analysis to discriminate between BC and BA found that type-1 cystic BA contained biliary duct cells that were CD56-positive

CT | CT scan of the abdominal cavity shows the relationship of the cyst with surrounding tissues, its continuity with the biliary tree, and the existence and staging of any accompanying malignancy. It is helpful to explain the intrahepatic dilations and the severity of the disease in people with Caroli’s disease (diffuse hepatic or localized segmental involvement) and type IVA cysts. Before doing an operation, a surgeon must consider certain factors since segmental lobectomy is a treatment option for localized type-IVA BC or Caroli's disease. Though MRCP is superior to CTC cholangiography (Computerized tomography cholangiography (CTC) following infusion of meglumine iodoxamate), in the visualization of the intrahepatic duct and the pancreatic system according to research by Fumino et al., The greatest benefit of CTC, however, is its capacity to generate clear pictures free of respiratory aberrations in infants, in whom conducting an accurate MRCP is particularly challenging.[9][11]

Cholangiography | Cholangiography shows that the cyst is continuous with the biliary tract which allows distinguishing BC from other intra-abdominal cysts such as pancreatic pseudocysts, biliary cystadenomas, and echinococcal cysts. The different cholangiography techniques are Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), magnetic resonance-cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), and intraoperative cholangiography.

ERCP ERCP Although ERCP is an invasive procedure, it has the potential to be therapeutic. Any related intraductal disease or an APBJ is accurately revealed by this test. It is possible to simultaneously do a therapeutic papillotomy with a type III BC.

MRCP The investigation of choice for preoperative imaging of the biliary tree is MRCP, which is non-invasive. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRCP can show the physiology of bile excretion, in contrast to standard T2-weighted MRC, which uses heavily T2-weighted and fat-suppressed pictures to show fluid-filled space. It is linked to particular characteristics of the hepatocytes which absorb gadoxetic acid. The bile ducts are visible on hepatobiliary phase T1-weighted imaging because gadoxetic acid is discharged into them.

A technetium-99 HIDA investigationA technetium-99 HIDA investigation It is advised to conduct a technetium-99 HIDA investigation to see how the BC and bile ducts are connected.

Treatment

Medical Therapy | Surgery | Primary Prevention | Secondary Prevention | Cost-Effectiveness of Therapy | Future or Investigational Therapies

General principles

Based on the type of cyst and any associated hepatobiliary pathology, choledochal cysts are surgically managed. Generally speaking, after the removal of all bile duct cysts, mucosa-to-mucosa biliary-enteric anastomosis should be used to restore bile flow. External drainage should be followed by long-term follow-up because of the risk of malignancy and strictures.

Type I cyst

Surgical excision is used to remove type II cysts from the common bile duct that develops as lateral diverticula. The common bile duct may need to be decompressed using a T-tube or the cyst's neck may need to be closed entirely, depending on how large it is at the junction with the bile duct. It is technically simpler to drain these cysts into the duodenum when they originate from the intrapancreatic part of the common bile duct.

Type II cyst

Surgical excision is used to remove type II cysts from the common bile duct that develops as lateral diverticula. The common bile duct may need to be decompressed using a T-tube or the cyst's neck may need to be closed entirely, depending on how large it is at the junction with the bile duct. It is simpler to drain these cysts into the duodenum when they originate from the intrapancreatic part of the common bile duct.

Type III cyst

The preferred treatments today are endoscopic sphincterotomy and cyst unroofing. Careful attention is required to safeguard these ducts and reanastomose them to the duodenal mucosa since the common bile duct and major pancreatic duct open into the cyst.

Type IV cyst

In type IVA cysts, there is controversy over how much tissue should be removed. It is advised to treat the condition with hepaticoenterostomy and removal of the extrahepatic component exclusively. Treatment of type IVB choledochal cysts, which include choledochocele, include Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy and transduodenal sphincteroplasty.

Case Studies

- ↑ Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K (1977). "Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst". Am. J. Surg. 134 (2): 263–9. PMID 889044.

- ↑ Caroli, J, et al. La dilatation polykystique congenitale des voies biliaires intrahepatiques. Essai del classification. Sem Hop Paris 1958;34:488

- ↑ Lu, S.C. et al. Diseases of the biliary tree. Textbook of Gastroenterology 1995:2212.

- ↑ Tandon, RK, et al. Caroli’s disease: A heterogeneous entity. Amer J Gastroent 1990;85:170. PMID 2301339

- ↑ Chalasani, N, et al. Spontaneous rupture of a bile duct. Amer J Gastroent 1997;92:1062. PMID 9177539

- ↑ Miller, WJ, et al. Imaging findings in Caroli’s disease. Am J Roenth 1995;165:333. PMID 7618550

- ↑ Torra, R, et al. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and Caroli’s disease. Kidney Int 1997;52:33. PMID 9211343

- ↑ Ros, E, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid treatment of primary hepatolithiasis in Caroli’s syndrome. Lancet 1993;342:404. PMID 8101905

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH (December 2009). "Choledochal cysts: part 2 of 3: Diagnosis". Can J Surg. 52 (6): 506–11. PMC 2792398. PMID 20011188.

- ↑ Kim OH, Chung HJ, Choi BG (January 1995). "Imaging of the choledochal cyst". Radiographics. 15 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1148/radiographics.15.1.7899614. PMID 7899614.

- ↑ Fumino S, Ono S, Kimura O, Deguchi E, Iwai N (July 2011). "Diagnostic impact of computed tomography cholangiography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography on pancreaticobiliary maljunction". J Pediatr Surg. 46 (7): 1373–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.01.026. PMID 21763837.