West nile virus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''For patient information click [[{{PAGENAME}} (patient information)|here]]'''. | |||

{{Taxobox | {{Taxobox | ||

| name = ''West Nile virus'' | | name = ''West Nile virus'' | ||

Revision as of 16:37, 5 August 2011

For patient information click here'.

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;"|West Nile virus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;" | Virus classification | ||||||||

|

| West Nile Fever | |

| ICD-10 | A92.3 |

|---|---|

| DiseasesDB | 30025 |

| MeSH | D014901 |

|

WikiDoc Resources for West nile virus |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on West nile virus Most cited articles on West nile virus |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on West nile virus |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on West nile virus at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on West nile virus Clinical Trials on West nile virus at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on West nile virus NICE Guidance on West nile virus

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on West nile virus Discussion groups on West nile virus Patient Handouts on West nile virus Directions to Hospitals Treating West nile virus Risk calculators and risk factors for West nile virus

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for West nile virus |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

West Nile virus (WNV) is a virus of the family Flaviviridae; part of the Japanese encephalitis (JE) antigenic complex of viruses, it is found in both tropical and temperate regions. It mainly infects birds, but is known to infect humans, horses, dogs, cats, bats, chipmunks, skunks, squirrels, and domestic rabbits. The main route of human infection is through the bite of an infected mosquito. Image reconstructions and cryoelectron microscopy reveal a 45-50 nm virion covered with a relatively smooth protein surface. This structure is similar to the dengue fever virus; both belong to the genus flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae. WNV is a positive-sense, single strand of RNA, it is between 11,000 and 12,000 nucleotides long which encode seven non-structural proteins and three structural proteins. The RNA strand is held within a nucleocapsid formed from 12 kDa protein blocks; the capsid is contained within a host-derived membrane altered by two viral glycoproteins.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Epidemiology

The human case-fatality rate in the U.S. has been 7% overall, and among patients with neuroinvasive WNV disease, 10%.

In general, the WNV transmission season in the U.S. is longer than that for other domestic arboviruses and requires longer periods of ecologic and human surveillance.

1. Northeastern and Midwestern U.S.

In the northeastern states in 2001-2002, human illness onset occurred as early as early July and as late as mid-November. During these same years, avian cases occurred as early as the first week of April and as late as the second week of December. Active ecological surveillance and enhanced passive surveillance for human cases should begin in early spring and continue through the fall until mosquito activity ceases because of cold weather. Surveillance in urban and suburban areas should be emphasized.

2. Southern U.S.

In 2001-2002, WNV circulated throughout the year, especially in the Gulf states. Although, in 2001-2002, human illness onset was reported as early as mid-May and June and as late as mid-December, equine and avian infections were reported in all 22 months of the year. Active ecologic surveillance and enhanced passive surveillance for human cases should be conducted year round in these areas.

3. Western U.S.

In 2002, WNV activity was first reported among humans and animals in Rocky Mountain states and among animals in Pacific coast states. These events occurred relatively late in the year (mid-August). Predicting the temporal characteristics of future WNV transmission seasons based on these limited reports is not possible. Despite this limitation, active ecological surveillance and enhanced passive surveillance for human cases beginning in early spring and continuing through the fall until mosquito activity ceases because of cold weather should be encouraged.

4. Other Areas of the Western Hemisphere

In 2002, Canada experienced a WNV epidemic in Ontario and Quebec provinces and an equine/avian epizootic that extended from the maritime provinces to Saskatchewan. Recent serologic evidence supports the conclusion that WNV has now reached Central America. Further spread to South America by migratory birds seems inevitable, if this has not already occurred. Development of surveillance systems capable of detecting WNV activity should be encouraged in the Caribbean and Central and South America. WNV surveillance should be integrated with dengue surveillance in these areas, and with yellow fever surveillance in areas where urban or peri-urban transmission of this virus occurs.

Demographics

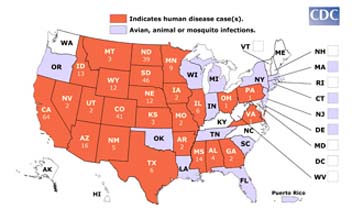

Map shows the distribution of avian, animal, or mosquito infection occurring during 2007 with number of human cases if any, by state. If West Nile virus infection is reported to CDC from any area of a state, that entire state is shaded.

Data table:

Avian, animal or mosquito WNV infections have been reported to CDC ArboNET from the following states in 2007: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Human cases have been reported in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wyoming.[2] [3]

West Nile virus has been described in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, west and central Asia, Oceania (subtype Kunjin), and most recently, North America.

Recent outbreaks of West Nile virus encephalitis in humans have occurred in Algeria (1994), Romania (1996 to 1997), the Czech Republic (1997), Congo (1998), Russia (1999), the United States (1999 to 2003), Canada (1999–2003), and Israel (2000).

Epizootics of disease in horses occurred in Morocco (1996), Italy (1998), the United States (1999 to 2001), and France (2000). In 2003, West Nile virus spread among horses in Mexico.

Risk Factors

Data on the risk factors associated with human and animal infection with WNV are required to develop more effective prevention strategies, particularly when educating the public to take specific prevention measures to reduce exposure to infection.

Target group

Audience members have different disease-related concerns and motivations for action. Proper message targeting permits better use of limited communication and prevention resources. The following are some audience groups that require specific targeting:

- Persons over age 50: While persons of any age can be infected with WNV, US

surveillance data indicate that persons over age 50 are at higher risk for severe disease and death due to WNV infection.

Collaborate with organizations that have an established relationship with mature adults, such as the AARP, senior centers, or programs for adult learners. Include images of older adults in your promotional material. Identify activities in your area where older adults may be exposed to mosquito bites (e.g. jogging, golf, gardening).

- Persons with outdoor exposure: While conclusive data are lacking, it is

reasonable to infer that persons engaged in extensive outdoor work or recreational activities are at greater risk of being bitten by WNV-infected mosquitoes. Develop opportunities to inform people engaged in outdoor activities about WNV. Encourage use of repellent and protective clothing, particularly if outdoors during evening, night, or early morning hours. Local spokespersons (e.g., union officials, job-site supervisors, golf pros, gardening experts) may be useful collaborators.

- Homeless persons: Extensive outdoor exposure and limited financial resources

in this group present special challenges. Application of repellents with DEET or permethrin to clothing may be most appropriate for this population. Work with social service groups in your area to reach this population segment.

- Persons who live in residences lacking window screens: The absence of intact

window/door screens is a likely risk factor for exposure to mosquito bites. Focus attention on the need to repair screens and resources to do so. Partner with community organizations that can assist elderly persons or others with financial or physical barriers to screen installation or repair. [4]

Screening

Commercial kits for human serologic diagnosis of WNV infection are currently in development. Until these kits are available, the CDC-defined IgM and IgG ELISA should be the front-line tests for serum and CSF.46-48 These ELISA tests are the most sensitive screening assays available. The HI and indirect immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test may also be used to screen samples for flavivirus antibodies. [5]

Pathophysiology & Etiology

WNV is a member of the family Flaviviridae (genus Flavivirus). Serologically, it is a member of the Japanese encephalitis virus antigenic complex, which includes St. Louis, Japanese, Kunjin, and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses. WNV was first isolated in the WN province of Uganda in 1937. Human and equine outbreaks have been recorded in portions of Africa, southern Europe, North America, and Asia. Although it is still not known when or how WNV was introduced into North America, international travel of infected persons to New York, importation of infected birds or mosquitoes, or migration of infected birds are all possibilities. [6] The virus is transmitted through mosquito vectors, which bite and infect birds. The birds are amplifying hosts, developing sufficient viral levels to transmit the infection to other biting mosquitoes which go on to infect other birds (in the Western hemisphere the American robin and the American crow are the most common carriers) and also humans. The infected mosquito species vary according to geographical area; in the US Culex pipiens (Eastern US), Culex tarsalis (Midwest and West), and Culex quinquefasciatus (Southeast) are the main sources.[1]

In mammals the virus does not multiply as readily, and it is believed that mosquitoes biting infected mammals do not further transmit the virus,[2] making mammals so-called dead-end infections.

A 2004 paper in Science found that Culex pipiens mosquitoes existed in two populations in Europe, one which bites birds and one which bites humans. In North America 40% of Culex pipiens were found to be hybrids of the two types which bite both birds and humans, providing a vector for West Nile virus. This is thought to provide an explanation of why the West Nile disease has spread more quickly in North America than Europe.

It was initially believed that direct human-to-human transmission was only caused by occupational exposure,[3] or conjunctival exposure to infected blood.[4] The US outbreak revealed novel transmission methods, through blood transfusion,[5] organ transplant,[6] intrauterine exposure,[7] and breast feeding.[8] Since 2003 blood banks in the US routinely screen for the virus amongst their donors.[9] As a precautionary measure, the UK's National Blood Service runs a test for this disease in donors who donate within 28 days of a visit to the United States or Canada.

History

Studies of phylogenetic lineages have determined that WNV emerged as a distinct virus around 1000 years ago.[10] This initial virus developed into two distinct lineages, Lineage 1 and its multiple profiles is the source of the epidemic transmission in Africa and throughout the world, while Lineage 2 remains as an Africa zoonose.

WNV was first isolated from a feverish adult woman in the West Nile District of Uganda in 1937 during research on yellow fever. A series of serosurveys in 1939 in central Africa found anti-WNV positive results ranging from 1.4% (Congo) to 46.4% (White Nile region, Sudan). It was subsequently identified in Egypt (1942) and India (1953), a 1950 serosurvey in Egypt found 90% of those over 40 years in age had WNV antibodies. The ecology was characterized in 1953 with studies in Egypt[11] and Israel.[12] The virus became recognized as a cause of severe human meningoencephalitis in elderly patients during an outbreak in Israel in 1957. The disease was first noted in horses in Egypt and France in the early 1960s and found to be widespread in southern Europe, southwest Asia and Australia.

The first appearance of West Nile virus in the Western hemisphere was in 1999 with encephalitis reported in humans and horses, and the subsequent spread in the United States may be an important milestone in the evolving history of this virus. The American outbreak began in the New York City area, including New Jersey and Connecticut, and the virus is believed to have entered in an infected bird or mosquito, although there is no clear evidence.[13] The US virus was very closely related to a lineage 1 strain found in Israel in 1998. Since the first North American cases in 1999, the virus has been reported throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America. There have been human cases and horse cases, and many birds are infected. Both the US and Israeli strains are marked by high mortality rates in infected avian populations, the presence of dead birds - especially corvidae - can be an early indicator of the arrival of the virus.

A very high level of media coverage through 2001/2002 raised public awareness of West Nile virus. This disproportionate coverage was most likely the result of successive appearances of the virus in new areas.

Environmentalists have condemned attempts to control the transmitting mosquitoes by spraying pesticide, saying that the detrimental health effects of spraying outweigh the relatively few lives which may be saved, and that there are more environmentally friendly ways of controlling mosquitoes. They also question the effectiveness of insecticide spraying, as they believe mosquitoes that are resting or flying above the level of spraying will not be killed; the most common vector in the northeastern U.S., Culex pipiens, is a canopy feeder. WNV was first isolated in the WN province of Uganda in 1937. Human and equine outbreaks have been recorded in portions of Africa, southern Europe, North America, and Asia.

In late summer 1999, the first domestically acquired human cases of West Nile (WN) encephalitis were documented in the U.S. The discovery of virus-infected, overwintering mosquitoes during the winter of 1999-2000 presaged renewed virus activity for the following spring and precipitated early season vector control and disease surveillance in New York City (NYC) and the surrounding areas. These surveillance efforts were focused on identifying and documenting WN virus (WNV) infections in birds, mosquitoes and equines as sentinel animals that could alert health officials to the occurrence of human disease. Surveillance tracked the spread of WNV throughout much of the U.S. between 2000 and 2002. By the end of 2002, WNV activity had been identified in 44 states and the District of Columbia. The 2002 WNV epidemic and epizootic resulted in reports of 4,156 reported human cases of WN disease (including 2,942 meningoencephalitis cases and 284 deaths), 16,741 dead birds, 6,604 infected mosquito pools, and 14,571 equine cases. The 2002 WNV epidemic was the largest recognized arboviral meningoencephalitis epidemic in the Western Hemisphere and the largest WN meningoencephalitis epidemic ever recorded. Significant human disease activity was recorded in Canada for the first time, and WNV activity was also documented in the Caribbean basin and Mexico. In 2002, 4 novel routes of WNV transmission to humans were documented for the first time: 1) blood transfusion, 2) organ transplantation, 3) transplacental transfer, and 4) breast-feeding.

Diagnosis

In 1999 in the U.S., the sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests of CSF for the diagnosis of human WN encephalitis cases was only 57%; more recent statistics are currently unavailable. Thus, PCR for the diagnosis of WN viral infections of the human central nervous system (CNS) continues to be experimental and should not replace tests for the detection of WNV-specific antibody in CSF and serum, tests that are far more sensitive.

A high clinical suspicion for arboviral encephalitis should be encouraged among health care providers. When the diagnosis is in doubt, appropriate clinical specimens should be submitted to CDC or another laboratory capable of performing reliable serologic testing for antibodies to domestic arboviruses. Testing of CSF and paired acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples should be strongly encouraged to maximize the accuracy of serologic results.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of equine encephalitis includes, but is not limited to, the other arboviral encephalitides and rabies.[7]

History and Symptoms

WNV has three different effects on humans. The first is an asymptomatic infection; the second is a mild febrile syndrome termed West Nile Fever;[14] the third is a neuroinvasive disease termed West Nile meningitis or encephalitis.[15] In infected individuals the ratio between the three states is roughly 110:30:1.[16]

The second, febrile stage has an incubation period of 3-8 days followed by fever, headache, chills, diaphoresis, weakness, lymphadenopathy, and drowsiness. Occasionally there is a short-lived truncal rash and some patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, or diarrhea. All symptoms are resolved within 7-10 days, although fatigue can last for some weeks and lymphadenopathy can take up to two months to resolve.

The more dangerous encephalitis is characterized by similar early symptoms but also a decreased level of consciousness, sometimes approaching near-coma. Deep tendon reflexes are hyperactive at first, later diminished. There are also extrapyramidal disorders. Recovery is marked by a long convalescence with fatigue.

More recent outbreaks have resulted in a deeper study of the disease and other, rarer, outcomes have been identified.The spinal cord may be infected, marked by anterior myelitis with or without encephalitis.[17] WNV-associated Guillain-Barré syndrome has been identified[18] and other rare effects include multifocal chorioretinitis (which has 100% specificity for identifying WNV infection in patients with possible WNV encephalitis)[19] hepatitis, myocarditis, nephritis, pancreatitis, and splenomegaly.[20][21][22]

Laboratory Findings

The basic laboratory diagnostic tests—and how they should be used at the national, state, and local level—are outlined below. The initial designation of reference and regional laboratories that can do all testing will be based on the availability of biosafety level 3 (BSL3) containment facilities.

Serologic Laboratory Diagnosis

Accurate interpretation of serologic findings requires knowledge of the specimen. For human specimens the following data must accompany specimens submitted for serology before testing can proceed or results can be properly interpreted and reported:

1) symptom onset date (when known);

2) date of sample collection;

3) unusual immunological status of patient (e.g., immunosuppression);

4) state and county of residence;

5) travel history in flavivirus-endemic areas;

6) history of prior vaccination against flavivirus disease (e.g., yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, or Central European encephalitis); and

7) brief clinical summary including clinical diagnosis (e.g., encephalitis, aseptic meningitis).

1. Human

a) Commercial kits for human serologic diagnosis of WNV infection are currently in development. Until these kits are available, the CDC-defined IgM and IgG ELISA should be the front-line tests for serum and CSF. These ELISA tests are the most sensitive screening assays available. The HI and indirect immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test may also be used to screen samples for flavivirus antibodies. Laboratories performing HI assays need be aware that the recombinant WNV antigens produced to date are not useful in the HI test; mouse brain source antigen (available from CDC) must be used in HI tests. The recombinant WNV antigen is available from commercial sources.

b) To date, the prototype WNV strains Eg101 or NY99 strains have performed equally well as antigens in diagnostic tests for WNV in North America.

c) To maintain Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendments (CLIA) certification, CLIA recommendations for positive and negative ranges should be followed, and laboratories doing WNV testing should participate in a proficiency testing program through experienced reference laboratories; CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases in Fort Collins, Colorado and the National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, Iowa both offer this type of program.

d) Because the ELISA can cross-react between flaviviruses (e.g., SLE, dengue, yellow fever, WN), it should be viewed as a screening test only. Initial serologically positive samples should be confirmed by neutralization test. Specimens ubmitted for arboviral serology should also be tested against other arboviruses known to be active or be present in the given area (e.g., test against SLE, WN and EEE viruses in Florida).

Primary Prevention

For humans to escape infection the avoidance of mosquitos is key[23] - remaining indoors(and not letting them indoors) at dawn and dusk, wearing light-colored clothing which protects arms and legs as well as trunk, using insect repellents on both skin and clothing (such as DEET, picaradin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus for skin and permethrin for clothes).[24] Treatment is purely supportive: analgesia for the pain of neurologic diseases; rehydration for nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea; encephalitis may also require airway protection and seizure management.

On August 19, 2006, the LA Times reported that the expected incidence rate of West Nile was dropping as the local population becomes exposed to the virus. "In countries like Egypt and Uganda, where West Nile was first detected, people became fully immune to the virus by the time they reached adulthood, federal health officials said." [8] However days later the CDC said that West Nile cases could reach a 3-year high because hot temperatures had allowed a larger brood of mosquitoes. [9] Reported cases in the U.S. in 2005 exceeded those in 2004 and cases in 2006 exceeded 2005's totals.

When dealing with West Nile virus, prevention is your best bet. Fighting mosquito bites reduces your risk of getting this disease, along with others that mosquitoes can carry. Take the commonsense steps below to reduce your risk:

*Avoid bites and illness

Use Insect Repellent: On exposed skin when you go outdoors. Use an EPA-registered insect repellent such as those with DEET, picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Even a short time being outdoors can be long enough to get a mosquito bite.

Clothing Can Help Reduce Mosquito Bites: When weather permits, wear long-sleeves, long pants and socks when outdoors. Mosquitoes may bite through thin clothing, so spraying clothes with repellent containing permethrin or another EPA-registered repellent will give extra protection. Don't apply repellents containing permethrin directly to skin. Do not spray repellent on the skin under your clothing.

Be Aware of Peak Mosquito Hours The hours from dusk to dawn are peak biting times for many species of mosquitoes. Take extra care to use repellent and protective clothing during evening and early morning -- or consider avoiding outdoor activities during these times.

*Clean out the mosquitoes from the places where you work and play

Drain Standing Water: Mosquitoes lay their eggs in standing water.Limit the number of places around your home for mosquitoes to breed by getting rid of items that hold water.

Install or Repair Screens: Some mosquitoes like to come indoors. Keep them outside by having well-fitting screens on both windows and doors. Offer to help neighbors whose screens might be in bad shape.

*Help your community control the disease

Report Dead Birds to Local Authorities: Dead birds may be a sign that West Nile virus is circulating between birds and the mosquitoes in an area. Over 130 species of birds are known to have been infected with West Nile virus, though not all infected birds will die. It's important to remember that birds die from many other causes besides West Nile virus.

Mosquito Control Programs: Check with local health authorities to see if there is an organized mosquito control program in your area. If no program exists, work with your local government officials to establish a program. The American Mosquito Control Association can provide advice, and their book Organization for Mosquito Control is a useful reference.

Clean Up: Mosquito breeding sites can be anywhere. Neighborhood clean up days can be organized by civic or youth organizations to pick up containers from vacant lots and parks, and to encourage people to keep their yards free of standing water. Mosquitoes don't care about fences, so it's important to control breeding sites throughout the neighborhood.

Something to remember: The chance that any one person is going to become ill from a single mosquito bite remains low. The risk of severe illness and death is highest for people over 50 years old, although people of all ages can become ill.[10]

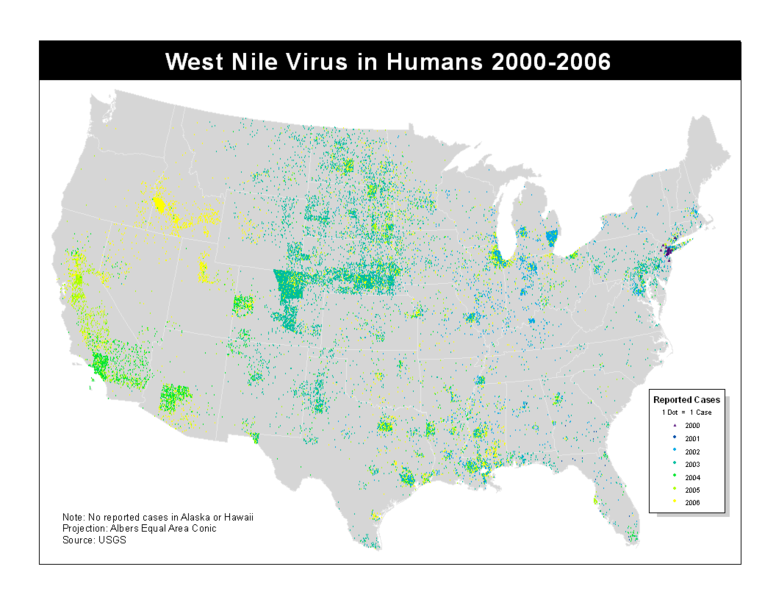

Recent outbreaks

United States: From 1999 through 2001, the CDC confirmed 149 cases of human West Nile virus infection, including 18 deaths. In 2002, a total of 4,156 cases were reported, including 284 fatalities. 13 cases in 2002 were contracted through blood transfusion. The cost of West Nile-related health care in 2002 was estimated at $200 million. The first human West Nile disease in 2003 occurred in June and one West Nile-infected blood transfusion was also identified that month. In the 2003 outbreak, 9,862 cases and 264 deaths were reported by the CDC. At least 30% of those cases were considered severe involving meningitis or encephalitis. In 2004, there were only 2,539 reported cases and 100 deaths. In 2005, there was a slight increase in the number of cases, with 3,000 cases and 119 deaths reported. 2006 saw another increase, with 4,261 cases and 174 deaths.

See also Progress of the West Nile virus in the United States

Canada: One human death occurred in 1999. In 2002, ten human deaths out of 416 confirmed and probable cases were reported by Canadian health officials. In 2003, 14 deaths and 1,494 confirmed and probable cases were reported. Cases were reported in 2003 in Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, and the Yukon. In 2004, only 26 cases were reported and two deaths; however, 2005 saw 239 cases and 12 deaths. By October 28, 2006, 127 cases and no deaths had been reported. One case was asymptomatic and only discovered through a blood donation. Currently in 2007, 445 Manitobans have confirmed cases of West Nile and two people have died with a third uncomfirmed but suspected.[25] 17 people have either tested positive or are suspected of having the virus in Saskatchewan, and only one person has tested positive in Alberta.[26]

Saskatchewan has reported 826 cases of West Nile plus three deaths.[27]

Israel: In 2000, the CDC found that there were 417 confirmed cases with 326 hospitalizations. 33 of these people died. The main clinical presentations were encephalitis (57.9%), febrile disease (24.4%), and meningitis (15.9%).[28]

Romania: In 1996-1997 about 500 cases occurred in Romania with a fatality rate of nearly 10%.

Surveillance methods

West Nile virus can be sampled from the environment by the pooling of trapped mosquitoes, testing avian blood samples drawn from wild birds and sentinel monkeys, as well as testing brains of dead birds found by various animal control agencies and the public. Testing of the mosquito samples requires the use of RT-PCR to directly amplify and show the presence of virus in the submitted samples. When using the blood sera of wild bird and sentinel chickens, samples must be tested for the presence of West Nile virus antibodies by use of immunohistochemistry (IHC)[29] or Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA).[30]

Dead birds, after necropsy, have their various tissues tested for virus by either RT-PCR or immunohistochemistry, where virus shows up as brown stained tissue because of a substrate-enzyme reaction.

Treatment research

Morpholino antisense oligos conjugated to cell penetrating peptides have been shown to partially protect mice from WNV disease.[31] There have also been attempts to treat infections using ribavirin, intravenous immunoglobulin, or alpha interferon.[32] GenoMed, a US biotech company, has found that blocking angiotensin II can treat the "cytokine storm" of West Nile virus encephalitis as well as other viruses.[33]

In 2007 the World Community Grid launched a project where by computer modeling of the West Nile Virus (and related viruses) thousands of small molecules are screened for their potential anti-viral properties in fighting the West Nile Virus. This is a project which by the use of computer simulations potential drugs will be identified which will directly attack the virus once a person is infected. This is a distributed process project similar to SETI@Home where the general public downloads the World Community Grid agent and the program (along with thousands of other users) screens thousands of molecules while their computer would be otherwise idle. If the user needs to use the computer the program sleeps. There are several different projects running, including a similar one screening for anti-AIDS drugs.

See also

References

- ↑ Hayes E B, Komar N, Nasci R S, Montgomery S P, Oleary D R, Campbell G L. "Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease." Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal 2005a; 11: 1167-1173

- ↑ Taylor R M, Hurlbut H S, Dressler H R, Spangler E W, Thrasher D. "Isolation of West Nile virus from Culex mosquitoes." Journal of the Egyptian Medical Association 1953; 36: 199-208

- ↑ CDC. "Laboratory-acquired West Nile virus infections - United States,2002." MMWR 2002c; 51: 1133-1135.

- ↑ Fonseca K, Prince G D, Bratvold J, Fox J D, Pybus M, Preksaitis J K, Tilley P. "West Nile virus infection and conjunctival exposure." Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal 3005; 11: 1648-1649.

- ↑ CDC. "Investigation of blood transfusion recipients with West Nile virus infections." MMWR 2002b; 51: 823.

- ↑ CDC. "West Nile virus infection in organ donor and transplant recipients - Georgia and Florida, 2002." MMWR 2002e; 51: 790.

- ↑ CDC. "Intrauterine West Nile virus infection - New York, 2002." MMWR 2002a; 51: 1135-1136.

- ↑ CDC. "Possible West Nile virus transmission to an infant through breast-feeding - Michigan, 2002." MMWR 2002d; 51: 877-878.

- ↑ CDC. "Detection of West Nile virus in blood donations - United States, 2003." MMWR 2003; 52: 769-772

- ↑ Galli M, Bernini F, Zehender G A. "The Great and West Nile virus encephalitis." Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal 2004 ; 10: 1332-1333

- ↑ Work T H, Hurlbut H S, Taylor R M. "Isolation of West Nile virus from hooded crow and rock pigeon in the Nile delta." Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 1953; 84: 719-722.

- ↑ Bernkopf H, Levine S, Nerson R. "Isolation of West Nile virus in Israel." Journal of Infectious Diseases 1953; 93: 207-218.

- ↑ Calisher C H. "West Nile virus in the New World: appearance, persistence, and adaptation to a new econiche - an opportunity taken." Viral Immunology 2000; 13: 411-414.

- ↑ Olejnik E. "Infectious adenitis transmitted by Culex molestus." Bull. Res. Counc. Isr. 1952; 2: 210-211.

- ↑ Smithburn K C, Jacobs H R. "Neutralization-tests against neurotropic viruses with sera collected in central Africa." Journal of Immunology 1942; 44: 923.

- ↑ Tsai T F, Popovici F, Cernescu C, Campbell G L, Nedelcu N I. "West Nile encephalitis epidemic in south eastern Romania." Lancet 1998; 352: 767-771

- ↑ Sejvar J J, Haddad M B, Tierney B C, Campbell G L, Marfin A A, VanGerpen J A, Fleischauer A, Leis A A, Stokic D S, Petersen L R. "Neurologic manifestations and outcome of West Nile virus infection." JAMA 2003; 290: 511-515.

- ↑ Ahmed S, Libman R, Wesson K, Ahmed F, Einberg K. "Guillain-Barre syndrome: an unusual presentation of West Nile virus infection." Neurology 2000; 55: 144-146.

- ↑ Abroug F, Ouanes-Besbes L, Letaief M, Ben Romdhane F, Khairallah M, Triki H, Bouzouiaia N. "A cluster study of predictors of severe West Nile virus infection." Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2006; 81: 12-16.

- ↑ Perelman A, Stern J. "Acute pancreatitis in West Nile Fever." American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1974; 23: 1150-1152.

- ↑ Omalu B I, Shakir A A, Wang G, Lipkin W I, Wiley C A. "Fatal fulminant pan-meningo-polioencephalitis due to West Nile virus." Brain Pathology 2003; 13: 465-472

- ↑ Mathiot C C, Georges A J, Deubel V. "Comparative analysis of West Nile virus strains isolated from human and animal hosts using monoclonal antibodies and cDNA restriction digest profiles." Res Virol 1990; 141: 533-543.

- ↑ Hayes E B, Gubler D J. "West Nile virus: epidemiology and clinical features of an emerging epidemic in the United States." Annual Review of Medicine 3006; 57: 181-194.

- ↑ Fradin M S, Day J F. "Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites." New England Journal of Medicine 3002; 347: 13-18.

- ↑ http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/wnv/index.html

- ↑ http://www.mytelus.com/ncp_news/article.en.do?pn=regional/alberta&articleID=2734169

- ↑ http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20070824/west_nile_sask_070824/20070824?hub=Health

- ↑ Chowers, MY (2001). "Clinical characteristics of the West Nile fever outbreak, Israel, 2000". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 7 (4): 675–8. PMID 11585531. Retrieved 2006-06-07. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Jozan, M (2003). "Detection of West Nile virus infection in birds in the United States by blocking ELISA and immunohistochemistry". Vector-borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 3 (3): 99–110. PMID 14511579. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hall, RA (1995). "Immunodominant epitopes on the NS1 protein of MVE and KUN viruses serve as targets for a blocking ELISA to detect virus-specific antibodies in sentinel animal serum". Journal of Virological Methods. 51 (2–3): 201–10. PMID 7738140. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Deas, Tia S (2007). "In vitro resistance selection and in vivo efficacy of morpholino oligomers against West Nile virus". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. PMID 17485503. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hayes E B, Sejvar J J, Zaki S R, Lanciotti R S, Bode A V, Campbell G L. "Virology, pathology, and clinical manifestations of West Nile virus disease." Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal 2005b; 11: 1174-1179.

- ↑ Moskowitz DW, Johnson FE. The central role of angiotensin I-converting enzyme in vertebrate pathophysiology. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4(13):1433-54. PMID: 15379656.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Nile virus. |

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) pages

- U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) pages

- Vaccine Research Center (VRC) - Information concerning WNV vaccine research studies

- US map of West Nile virus

- Canadian Case Surveillance

- L. Peterson, M. Marphin. "West Nile virus: A Primer for the Clinician", Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 137 No. 3, August 2002.

- D. J. White, D. L. Morse (eds.). "West Nile virus: Detection, Surveillance, and Control", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 951, 2001.

- Nature news article on West Nile paralysis

- CBC News Coverage of West Nile in Canada

- West Nile Fever in Europe

- Encephalitis Global, Inc.

- Harvard University fact sheet on West Nile Virus

- West Nile Cases Drop as Immunities Emerge, Experts Say

- Nash D, Mostashari FM, Fine A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001 June 14;344(24):1807-14 The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City Area in 1999

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D.

zh-min-nan:Se Nî-lô-hô pēⁿ-to̍k ca:Virus del Nil Occidental de:West-Nil-Virus id:Virus West Nile it:Virus del Nilo occidentale he:קדחת הנילוס המערבי lt:Nilo karštinė nl:West-Nijlvirus