Romano-Ward syndrome

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Synonyms and keywords: Autosomal Dominant Long QT syndrome, Long QT syndrome without deafness, LQTS, Romano-Ward Long QT syndrome, RWS, Ward-Romano syndrome, Romano-Ward syndrome

Overview

Romano-Ward syndrome is a rare congenital genetic condition with autosomal dominant inheritance pattern which leads to abnormal ventricular myocardial repolarization which results in long QT syndrome (LQTS). Among all other long QT syndrome (LQTS) Romano-Ward syndrome is the most common one. Romano-Ward syndrome is due to mutation in LQT1, LQT2 and LQT3 genes. Romano-Ward syndrome has a purely cardiac phenotype of QT prolongation in contrast to Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome which has both sensorineural deafness and cardiac events.

Historical Perspective

- In 1963, Romano and in 1964, Ward was the first to discover almost similar condition like Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome and they named it as Romano-Ward syndrome.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

- In 1990, LQTS 1, LQTS 2 and LQTS 3 the three main types of LQTS and their genes involved and proteins involved are identified for the first time.

Classification

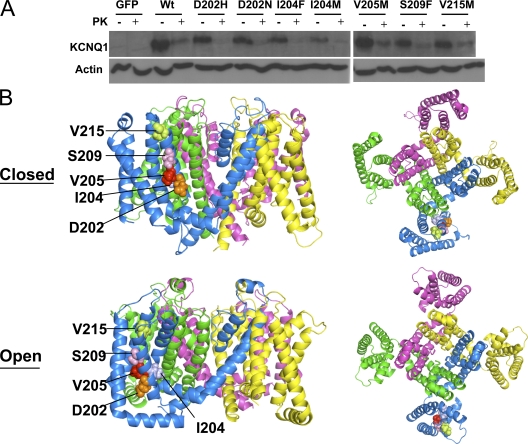

LQT1-associated S3 mutants traffic to the plasma membrane in ltk− cells. (A) Western blot of WT and mutant KCNQ1+KCNE1 proteins expressed in ltk− cells, untreated and treated with proteinase K (PK) to distinguish surface-expressed channel from internal. After normalization to actin for control of loading, the percent surface protein was determined from the density of bands before and after proteinase K treatment (n = 3) and was found to be: WT, 73%; D202H, 91%; D202N, 80%; I204F, 80%; I204M, 90%; V205M, 75%; S209F, 82%; V215M, 75%. (B) Model of KCNQ1 tetrameric channels showing the locations of S3 mutations in space fill from the side and the extracellular face, with each subunit a different color. Case courtesy by Jodene Eldstrom et al[8]

| LQT | Gene Involved | Chromosome involved | Protein Involved | Ion channel Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQT 1 | KCNQ1 | 11p15.5 | Iks a subunit | Iks |

| LQT 2 | HERG | 7q35-36 | Ikr a subunit | Ikr |

| LQT 3 | SCN5A | 3q21-24 | Sodium channel | INa |

| LQT 4 | NOT KNOWN | 4q25-27 | Unknown | Unknown |

| LQT 5 | KCNE1 | 21q22.1-2 | Iks a subunit | Iks |

| LQT 6 | KCNE2 | 21q22.1 | Ikr b subunit | Ikr |

Pathophysiology

- Mutations in the ANK2, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNH2, KCNQ1, and SCN5A genes cause Romano-Ward syndrome[13][14]

- The proteins made by most of these genes form channels that transport positively-charged ions, such as potassium and sodium, in and out of cells

- In cardiac muscle, these potassium and sodium ion channels play critical roles in maintaining the heart's normal rhythm

- Mutations in any of these genes alter the structure or function of channels, which changes the flow of ions between cells and results in abnormal heart rhythm

- A disruption in ion transport alters the way the heartbeats, leading to the abnormal heart rhythm characteristic of Romano-Ward syndrome

- Unlike most genes involved in Romano-Ward syndrome, the ANK2 gene does not produce an ion channel but instead the protein made by the ANK2 gene ensures that other proteins, particularly ion channels, are inserted into the cell membrane appropriately

- Then the truncated protein results in impairing potassium channel function, which is known to result in long QT syndrome.

Causes

Genetic Causes

- Romano-Ward syndrome is caused by a mutation in the ANK2, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNH2, KCNQ1, and SCN5A genes.[15]

Differentiating Romano-Ward syndrome from other Diseases

Romano-Ward syndrome must be differentiated from Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS), Timothy syndrome, Andersen-Tawil syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

Epidemiology and Demographics

Incidence

- The incidence of Romano-Ward syndrome is approximately 1 in 2,000 people worldwide individuals worldwide.

Prevalence

- The prevalence of Romano-Ward syndrome is approximately 1:20 000 to 1:5000 individuals worldwide.[24]

- The prevalence of Romano-Ward syndrome is approximately 1 in 2000 live births.

Race

- There is no racial predilection to Romano-Ward syndrome.

Gender

- Romano-Ward syndrome affects men and women equally.

Risk Factors

- Apart from the genetic mutations in ANK2, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNH2, KCNQ1, and SCN5A genes, there are some risk factors associated with Romano-Ward syndrome.

- Other common risk factors in the development of Romano-Ward syndrome symptoms include sudden sleep arousal, exercise and intense or sudden emotion which include the following:[25][26]

- Competitive sports, amusement park rides, frightening movies, jumping into cold water etc

- Based on the genotype the triggering events may differ, for example:[27]

- In patients with LQT1 genotype exercise or swimming is the trigger for cardiac events due to stimulation of vasovagal reflex

- In patients with LQT2 genotype emotions, exposure to auditory stimuli like door bells, telephone ring can trigger the cardiac events

- In patients with LQT3 genotype cardiac events can be triggered during sleep

Screening

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for Romano-Ward syndrome.

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Natural History

- The symptoms of Romano-Ward syndrome usually develop in the second decade of life, and start with symptoms such as syncope and palpitations.

- The symptoms of Romano-Ward syndrome typically decreases with increase in the age, after the age of 40 years the symptoms are less common than usual.

Complications

- Common complications of Romano-Ward syndrome include:[28]

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Cardiac arrest

- Seizures

- Sudden cardiac death: Most commonly occurs during the sleep

Prognosis

- The prognosis varies with the type of genes and mutations involved in the pathogenesis of the Romano-Ward syndrome patients. However, the prognosis is generally range from poor to good

Diagnosis

Diagnostic study of choice

- Along with clinical features and molecular genetic testing is the gold standard test for the diagnosis of Romano-Ward syndrome which includes single-gene testing, use of a multigene testing panel, and more comprehensive genomic testing.

- The following result of molecular genetic testing is confirmatory of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS):

History and Symptoms

Common Symptoms

Common symptoms of Romano-Ward syndrome include:[29][30]

- Presyncope

- Syncope

- Palpitations: All the first three symptoms are normally self limiting and may reoccur most of the time

- Tachycardia

- Ventricular arrhythmia

- Torsade de pointes

Less Common Symptoms

Less common symptoms of Romano-Ward syndrome include

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Seizures: Patients with seizures in Romano-Ward syndrome usally not respond to anti-epileptic medications.

- Atrial fibrillation

Physical Examination

- In patients with long QT syndrome (LQTS) physical examination usually limited and do not indicate a diagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS).

Vital Signs

- Bradycardia with regular pulse for their age

Heart

- Cardiovascular examination of patients with Romano-Ward syndrome should be done to rule out other causes of arrhythmic and syncopal events which include the diseases like heart murmurs caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valvular defects

Laboratory Findings

- There are no diagnostic laboratory findings associated with Romano-Ward syndrome.

- Laboratory findings that should be considered and checked routinely in Romano-Ward syndrome include:

Electrocardiogram

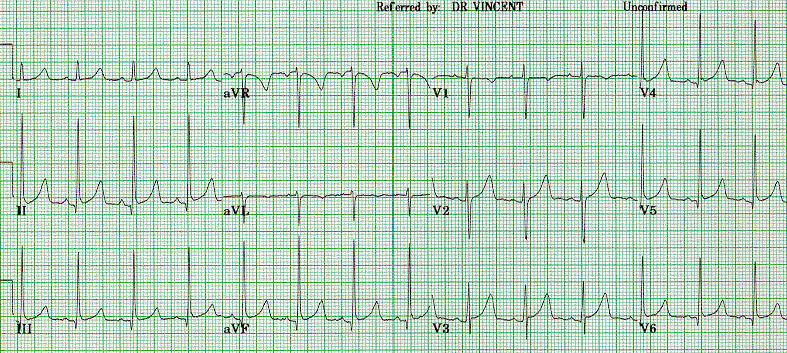

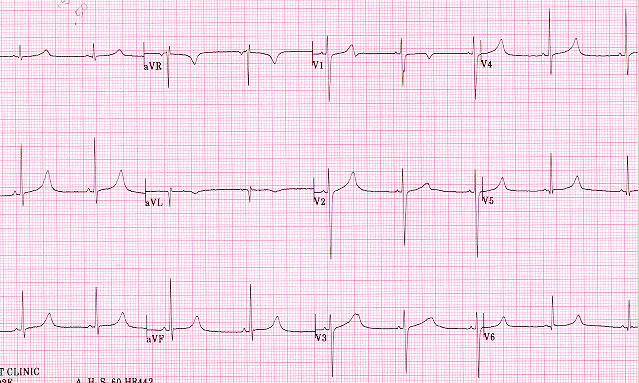

Romano-Ward syndrome with the broad-based T pattern. Case courtesy by G. Michael Vincent, MD[32] - Prolongation of the QTc interval greater than 500 msec

- Usually defined as longer than 440 ms for males and 460 ms for females on the electrocardiogram

- Tachyarrhythmias: due to abnormal cardiac depolarization and cardiac repolarization

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Torsade de pointes ventricular tachycardia

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Prolongation of the QTc interval greater than 500 msec

X Ray

- There are no x-ray findings associated with Romano-Ward syndrome.

Ultrasound

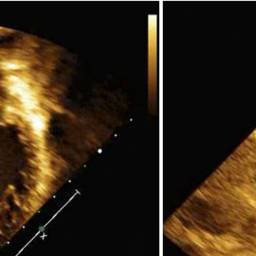

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing severe dilation and systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle. Case courtesy by Kiona Y. Allen, MD[39]

MRI

- Chest MRI may be helpful in the excluding diagnosis of Romano-Ward syndrome with other diseases that may cause the arrhythmias which include:[41]

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- Pharmacologic medical therapy is recommended among patients with [disease subclass 1], [disease subclass 2], and [disease subclass 3].

- Pharmacologic medical therapies for [disease name] include (either) [therapy 1], [therapy 2], and/or [therapy 3].

- Empiric therapy for [disease name] depends on [disease factor 1] and [disease factor 2].

- Patients with [disease subclass 1] are treated with [therapy 1], whereas patients with [disease subclass 2] are treated with [therapy 2].

Disease Name

- 1 Stage 1 - Name of stage

- 1.1 Specific Organ system involved 1

- 1.1.1 Adult

- Preferred regimen (1): drug name 100 mg PO q12h for 10-21 days (Contraindications/specific instructions)

- Preferred regimen (2): drug name 500 mg PO q8h for 14-21 days

- Preferred regimen (3): drug name 500 mg q12h for 14-21 days

- Alternative regimen (1): drug name 500 mg PO q6h for 7–10 days

- Alternative regimen (2): drug name 500 mg PO q12h for 14–21 days

- Alternative regimen (3): drug name 500 mg PO q6h for 14–21 days

- 1.1.2 Pediatric

- 1.1.2.1 (Specific population e.g. children < 8 years of age)

- Preferred regimen (1): drug name 50 mg/kg PO per day q8h (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- Preferred regimen (2): drug name 30 mg/kg PO per day in 2 divided doses (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- Alternative regimen (1): drug name10 mg/kg PO q6h (maximum, 500 mg per day)

- Alternative regimen (2): drug name 7.5 mg/kg PO q12h (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- Alternative regimen (3): drug name 12.5 mg/kg PO q6h (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- 1.1.2.2 (Specific population e.g. 'children < 8 years of age')

- Preferred regimen (1): drug name 4 mg/kg/day PO q12h(maximum, 100 mg per dose)

- Alternative regimen (1): drug name 10 mg/kg PO q6h (maximum, 500 mg per day)

- Alternative regimen (2): drug name 7.5 mg/kg PO q12h (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- Alternative regimen (3): drug name 12.5 mg/kg PO q6h (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- 1.1.2.1 (Specific population e.g. children < 8 years of age)

- 1.1.1 Adult

- 1.2 Specific Organ system involved 2

- 1.2.1 Adult

- Preferred regimen (1): drug name 500 mg PO q8h

- 1.2.2 Pediatric

- Preferred regimen (1): drug name 50 mg/kg/day PO q8h (maximum, 500 mg per dose)

- 1.2.1 Adult

- 1.1 Specific Organ system involved 1

Causes

Mutations in the ANK2, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNH2, KCNQ1, and SCN5A genes cause Romano-Ward syndrome. The proteins made by most of these genes form channels that transport positively-charged ions, such as potassium and sodium, in and out of cells.

In cardiac muscle, these ion channels play critical roles in maintaining the heart's normal rhythm. Mutations in any of these genes alter the structure or function of channels, which changes the flow of ions between cells.

A disruption in ion transport alters the way the heartbeats, leading to the abnormal heart rhythm characteristic of Romano-Ward syndrome.

Unlike most genes related to Romano-Ward syndrome, the ANK2 gene does not produce an ion channel. The protein made by the ANK2 gene ensures that other proteins, particularly ion channels, are inserted into the cell membrane appropriately.

A mutation in the ANK2 gene likely alters the flow of ions between cells in the heart, which disrupts the heart's normal rhythm and results in the features of Romano-Ward syndrome.

References

- ↑ Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K; et al. (1993). "GeneReviews®". PMID 20301308.

- ↑ Ackerman MJ, Siu BL, Sturner WQ, Tester DJ, Valdivia CR, Makielski JC; et al. (2001). "Postmortem molecular analysis of SCN5A defects in sudden infant death syndrome". JAMA. 286 (18): 2264–9. doi:10.1001/jama.286.18.2264. PMID 11710892.

- ↑ Arnestad M, Crotti L, Rognum TO, Insolia R, Pedrazzini M, Ferrandi C; et al. (2007). "Prevalence of long-QT syndrome gene variants in sudden infant death syndrome". Circulation. 115 (3): 361–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658021. PMID 17210839.

- ↑ Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Napolitano C; et al. (2001). "Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias". Circulation. 103 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1161/01.cir.103.1.89. PMID 11136691.

- ↑ Wedekind H, Bajanowski T, Friederich P, Breithardt G, Wülfing T, Siebrands C; et al. (2006). "Sudden infant death syndrome and long QT syndrome: an epidemiological and genetic study". Int J Legal Med. 120 (3): 129–37. doi:10.1007/s00414-005-0019-0. PMID 16012827.

- ↑ Juang JJ, Horie M (2016). "Genetics of Brugada syndrome". J Arrhythm. 32 (5): 418–425. doi:10.1016/j.joa.2016.07.012. PMC 5063259. PMID 27761167.

- ↑ Thomas D, Wimmer AB, Karle CA, Licka M, Alter M, Khalil M; et al. (2005). "Dominant-negative I(Ks) suppression by KCNQ1-deltaF339 potassium channels linked to Romano-Ward syndrome". Cardiovasc Res. 67 (3): 487–97. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.003. PMID 15950200.

- ↑ "Mechanistic basis for LQT1 caused by S3 mutations in the KCNQ1 subunit of IKs".

- ↑ Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G (1996). "K(V)LQT1 and lsK (minK) proteins associate to form the I(Ks) cardiac potassium current". Nature. 384 (6604): 78–80. doi:10.1038/384078a0. PMID 8900282.

- ↑ Vincent GM (2002) The long QT syndrome. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2 (4):127-42. PMID: 16951729

- ↑ Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Caspi O, Winterstern A; et al. (2011). "Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells". Nature. 471 (7337): 225–9. doi:10.1038/nature09747. PMID 21240260.

- ↑ Vincent GM (1998). "The molecular genetics of the long QT syndrome: genes causing fainting and sudden death". Annu Rev Med. 49: 263–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.263. PMID 9509262.

- ↑ Lehnart SE, Ackerman MJ, Benson DW, Brugada R, Clancy CE, Donahue JK; et al. (2007). "Inherited arrhythmias: a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases workshop consensus report about the diagnosis, phenotyping, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches for primary cardiomyopathies of gene mutations affecting ion channel function". Circulation. 116 (20): 2325–45. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711689. PMID 17998470.

- ↑ Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL; et al. (1996). "Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel". Nature. 384 (6604): 80–3. doi:10.1038/384080a0. PMID 8900283.

- ↑ Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL; et al. (1996). "Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel". Nature. 384 (6604): 80–3. doi:10.1038/384080a0. PMID 8900283.

- ↑ Thomas D, Wimmer AB, Karle CA, Licka M, Alter M, Khalil M; et al. (2005). "Dominant-negative I(Ks) suppression by KCNQ1-deltaF339 potassium channels linked to Romano-Ward syndrome". Cardiovasc Res. 67 (3): 487–97. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.003. PMID 15950200.

- ↑ Juang JJ, Horie M (2016). "Genetics of Brugada syndrome". J Arrhythm. 32 (5): 418–425. doi:10.1016/j.joa.2016.07.012. PMC 5063259. PMID 27761167.

- ↑ Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ (2009). "Cardiomyopathic and channelopathic causes of sudden unexplained death in infants and children". Annu Rev Med. 60: 69–84. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.052907.103838. PMID 18928334.

- ↑ Wedekind H, Bajanowski T, Friederich P, Breithardt G, Wülfing T, Siebrands C; et al. (2006). "Sudden infant death syndrome and long QT syndrome: an epidemiological and genetic study". Int J Legal Med. 120 (3): 129–37. doi:10.1007/s00414-005-0019-0. PMID 16012827.

- ↑ Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Napolitano C; et al. (2001). "Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias". Circulation. 103 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1161/01.cir.103.1.89. PMID 11136691.

- ↑ Arnestad M, Crotti L, Rognum TO, Insolia R, Pedrazzini M, Ferrandi C; et al. (2007). "Prevalence of long-QT syndrome gene variants in sudden infant death syndrome". Circulation. 115 (3): 361–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658021. PMID 17210839.

- ↑ Ackerman MJ, Siu BL, Sturner WQ, Tester DJ, Valdivia CR, Makielski JC; et al. (2001). "Postmortem molecular analysis of SCN5A defects in sudden infant death syndrome". JAMA. 286 (18): 2264–9. doi:10.1001/jama.286.18.2264. PMID 11710892.

- ↑ Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K; et al. (1993). "GeneReviews®". PMID 20301308.

- ↑ Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, Pedrazzini M, Besana A, Bosi G; et al. (2009). "Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome". Circulation. 120 (18): 1761–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863209. PMC 2784143. PMID 19841298.

- ↑ Schwartz, Peter J.; Spazzolini, Carla; Crotti, Lia; Bathen, Jørn; Amlie, Jan P.; Timothy, Katherine; Shkolnikova, Maria; Berul, Charles I.; Bitner-Glindzicz, Maria; Toivonen, Lauri; Horie, Minoru; Schulze-Bahr, Eric; Denjoy, Isabelle (2006). "The Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome". Circulation. 113 (6): 783–790. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592899. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ Schwartz PJ, Spazzolini C, Crotti L, Bathen J, Amlie JP, Timothy K; et al. (2006). "The Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome: natural history, molecular basis, and clinical outcome". Circulation. 113 (6): 783–90. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592899. PMID 16461811.

- ↑ Vincent GM (1998). "The molecular genetics of the long QT syndrome: genes causing fainting and sudden death". Annu Rev Med. 49: 263–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.263. PMID 9509262.

- ↑ Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ (2009). "Cardiomyopathic and channelopathic causes of sudden unexplained death in infants and children". Annu Rev Med. 60: 69–84. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.052907.103838. PMID 18928334.

- ↑ Vincent GM (1998). "The molecular genetics of the long QT syndrome: genes causing fainting and sudden death". Annu Rev Med. 49: 263–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.263. PMID 9509262.

- ↑ Engelstein ED (2003). "Long QT syndrome: a preventable cause of sudden death in women". Curr Womens Health Rep. 3 (2): 126–34. PMID 12628082.

- ↑ "The long QT syndrome".

- ↑ "The Long QT Syndrome".

- ↑ Goldenberg I, Horr S, Moss AJ, Lopes CM, Barsheshet A, McNitt S; et al. (2011). "Risk for life-threatening cardiac events in patients with genotype-confirmed long-QT syndrome and normal-range corrected QT intervals". J Am Coll Cardiol. 57 (1): 51–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.038. PMC 3332533. PMID 21185501.

- ↑ Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Peterson DR, McNitt S, Zareba W, Andrews ML; et al. (2008). "Risk factors for aborted cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death in children with the congenital long-QT syndrome". Circulation. 117 (17): 2184–91. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701243. PMC 3944375. PMID 18427136.

- ↑ Vincent GM (1998). "The molecular genetics of the long QT syndrome: genes causing fainting and sudden death". Annu Rev Med. 49: 263–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.263. PMID 9509262.

- ↑ Hobbs, Jenny B.; Peterson, Derick R.; Moss, Arthur J.; McNitt, Scott; Zareba, Wojciech; Goldenberg, Ilan; Qi, Ming; Robinson, Jennifer L.; Sauer, Andrew J.; Ackerman, Michael J.; Benhorin, Jesaia; Kaufman, Elizabeth S.; Locati, Emanuela H.; Napolitano, Carlo; Priori, Silvia G.; Towbin, Jeffrey A.; Vincent, G. Michael; Zhang, Li (2006). "Risk of Aborted Cardiac Arrest or Sudden Cardiac Death During Adolescence in the Long-QT Syndrome". JAMA. 296 (10): 1249. doi:10.1001/jama.296.10.1249. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ↑ Friedrichs S, Malan D, Sasse P (2013). "Modeling long QT syndromes using induced pluripotent stem cells: current progress and future challenges". Trends Cardiovasc Med. 23 (4): 91–8. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2012.09.006. PMID 23266156.

- ↑ Hofman N, Wilde AA, Kääb S, van Langen IM, Tanck MW, Mannens MM; et al. (2007). "Diagnostic criteria for congenital long QT syndrome in the era of molecular genetics: do we need a scoring system?". Eur Heart J. 28 (5): 575–80. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl355. PMID 17090615.

- ↑ "Familial long QT syndrome and late development of dilated cardiomyopathy in a child with a KCNQ1 mutation: A case report".

- ↑ Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ (2009). "Cardiomyopathic and channelopathic causes of sudden unexplained death in infants and children". Annu Rev Med. 60: 69–84. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.052907.103838. PMID 18928334.

- ↑ Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ (2009). "Cardiomyopathic and channelopathic causes of sudden unexplained death in infants and children". Annu Rev Med. 60: 69–84. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.052907.103838. PMID 18928334.