Pyloric stenosis

| Pyloric stenosis | |

| |

|---|---|

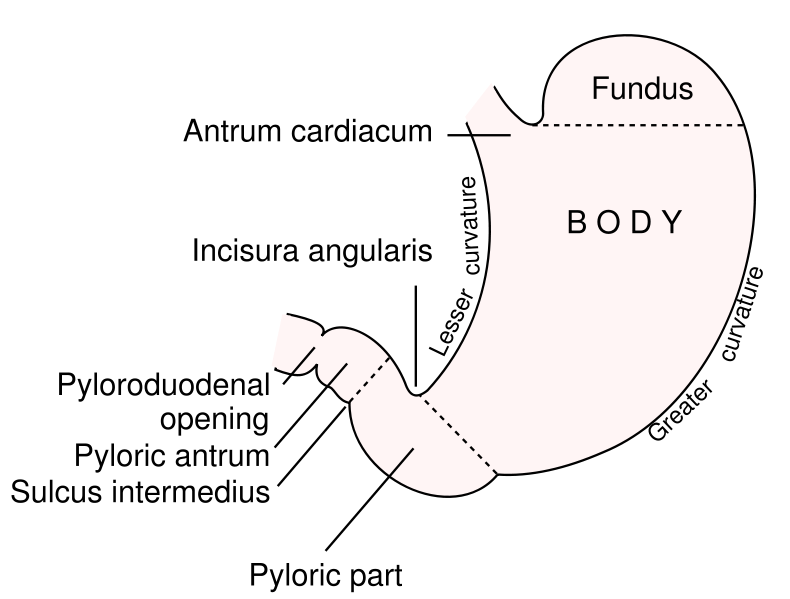

| Outline of stomach, showing its anatomical landmarks, including the pylorus. | |

| ICD-10 | K31.1, Q40.0 |

| ICD-9 | 537.0, 750.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 11060 Template:DiseasesDB2 |

| MedlinePlus | 000970 |

| eMedicine | emerg/397 radio/358 |

| MeSH | D046248 |

For patient information click here

Template:Search infobox Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Pyloric stenosis (or infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis) is a condition that causes severe vomiting in the first few months of life. There is narrowing (stenosis) of the opening from the stomach to the intestines, due to spasm and hypertrophy of the muscle surrounding this opening (the pylorus). It is uncertain whether there is a real congenital narrowing or whether there is a functional hypertrophy of the muscle which develops in the first few weeks of life.

Males are more commonly affected than females, with firstborn males affected about four times as often, and there is a genetic predisposition for the disease.[1] It is commonly associated with people of Jewish ancestry.[2] Caucasians and babies with blood type B or O are more likely to be affected.[1]

Pyloric stenosis also occurs in adults where the cause is usually a narrowed pylorus due to scarring from chronic peptic ulceration. This is a completely different condition from the infantile form.

Pathophysiology

The gastric outlet obstruction due to the hypertrophic pylorus impairs emptying of gastric contents into the duodenum. As a consequence, all ingested food and gastric secretions can only exit via vomiting, which can be of a projectile nature. The vomited material does not contain bile because the pyloric obstruction prevents entry of duodenal contents (containing bile) into the stomach.

This results in loss of gastric acid (hydrochloric acid). The chloride loss results in hypochloremia which impairs the kidney's ability to excrete bicarbonate. This is the significant factor that prevents correction of the alkalosis.[3]

A secondary hyperaldosteronism develops due to the hypovolaemia. The high aldosterone levels causes the kidneys to:

- avidly retain Na+ (to correct the intravascular volume depletion)

- excrete increased amounts of K+ into the urine (resulting in hypokalaemia).

The body's compensatory response to the metabolic alkalosis is hypoventilation resulting in an elevated arterial pCO2.

Symptoms

Babies with this condition usually present within the first few weeks to months of life with progressively worsening vomiting. The vomiting is often described as non-bile stained and "projectile vomiting", because it is more forceful than the usual spittiness (gastroesophageal reflux) seen at this age. Some infants present with poor feeding and weight loss, but others demonstrate normal weight gain.

Diagnosis

A careful history and physical examination, often supplemented by radiographic studies are required for diagnosis. There should be suspicion for pyloric stenosis in any young infant with severe vomiting. On exam, palpation of the abdomen may reveal a mass in the epigastrium. This mass, which consists of the enlarged pylorus, is referred to as the 'olive,' and is sometimes evident after the infant is given formula to drink. It is an elusive diagnostic skill requiring much patience and experience. There are often palpable (or even visible) peristaltic waves due to stomach trying to force its contents past the narrowed pyloric outlet.

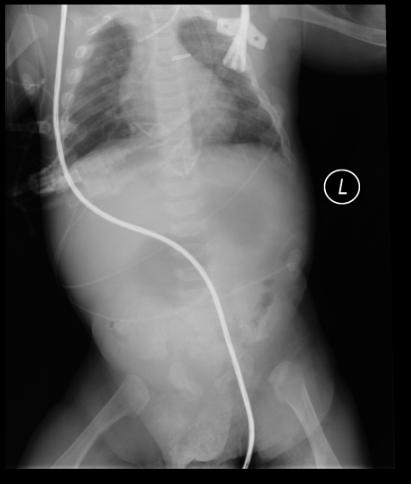

At this point, most cases of pyloric stenosis are diagnosed/confirmed with ultrasound, if available, showing the thickened pylorus. Although somewhat less useful, an upper GI series (x-rays taken after the baby drinks a special contrast agent) can be diagnostic by showing the narrowed pyloric outlet filled with a thin stream of contrast material; a "string sign" or the "railroad track sign". For either type of study, there are specific measurement criteria used to identify the abnormal results. Plain x-rays of the abdomen are not useful, except when needed to rule out other problems.

Blood tests will reveal hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis due to loss of gastric acid (which contain hydrochloric acid and potassium) via persistent vomiting; these findings can be seen with severe vomiting from any cause.

Upper GI Series

- The pyloric canal is outlined by a string of contrast material coursing through the mucosal interstices, termed the string sign; or by several linear tracts of contrast material separated by the intervening mucosa. The latter is termed the double-track sign. This sign demonstrates the intervening redundant mucosa outlined as a filling defect by the contrast material.

- UGI is performed with the infant in the right anterior oblique position, to facilitate gastric emptying.

- Fluoroscopic observations include vigorous active peristalsis resembling a caterpillar and coming to an abrupt stop at the pyloric antrum, outlining the external thickened muscle as an extrinsic impression, termed the shoulder sign.

- Luminal barium may be transiently trapped between the peristaltic wave and the muscle, and this is termed the tit sign.

- Eventual success of gastric peristaltic activity will propel contrast material through the pyloric mucosal interstices, with the appearance as either the string sign or the double-track sign, although at times more than one layer of contrast material may be appreciated in the mucosal filling defect.

(Images courtesy of RadsWiki)

Ultrasonography

- USG demonstrates the thickened prepyloric antrum bridging the duodenal bulb and distended stomach.

- Demonstration of the pylorus is achieved by identifying the duodenal cap, distended stomach, and intervening pyloric channel.

- In patients with IHPS, the muscle is hypertrophied to a variable degree, and the intervening mucosa is crowded, thickened to a variable degree, and protrudes into the distended portion of the antrum (nipple sign) and can be seen filling the lumen on transverse sections.

- The length of the hypertrophied canal is variable and may range from as little as 14 mm to more than 20 mm.

- The numeric value for the lower limit of muscle thickness has varied in reports in the literature, ranging between 3.0 and 4.5 mm.

- The actual numeric value is less important than the overall morphology of the canal and the real-time observations.

(Images courtesy of RadsWiki)

Treatment

Infantile pyloric stenosis is typically managed with surgery.

It is important to understand that the danger of pyloric stenosis comes from the dehydration and electrolyte disturbance rather than the underlying problem itself. Therefore, the baby must be initially stabilized by correcting the dehydration and hypochloremic alkalosis with IV fluids. This can usually be accomplished in about 24-48 hours.

Definitive treatment of pyloric stenosis is with surgical pyloromyotomy (dividing the muscle of the pylorus to open up the gastric outlet). This is a relatively straightforward surgery that can be done through a single larger incision or laparoscopically (through several tiny incisions), depending on the surgeon's experience and preference.

Once the stomach can empty into the duodenum, feeding can commence.

There is occasionally recurrence in the immediate post-operative period, but the condition generally has no longterm impact on the child's future.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dowshen, Steven (November 2007). "Pyloric Stenosis". The Nemours Foundation. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ Probable autosomal dominant infantile pyloric stenosis in a large kindred. Retrieved September 14, 2007

- ↑ Kerry Brandis, Acid-Base Physiology. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

Additional Resources

- Hulka F, Campbell TJ, Campbell JR, Harrison MW. Evolution in the recognition of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatrics 1997;100(2):E9. Fulltext. PMID 9233980.

- Template:Chorus

- UCL Institute of Child Health

Template:SIB Template:Gastroenterology Template:Congenital malformations and deformations of digestive system