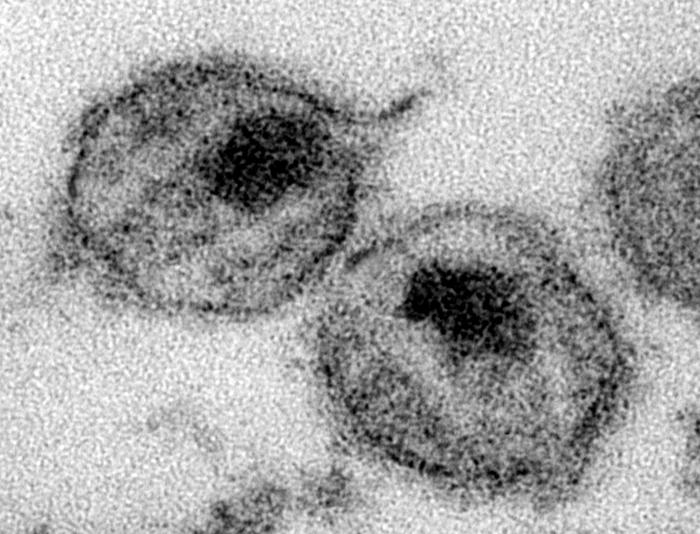

HIV AIDS pathophysiology

|

AIDS Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

HIV AIDS pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of HIV AIDS pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for HIV AIDS pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Ammu Susheela, M.D. [2]

Overview

Human Immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS by depleting CD4+ T helper lymphocytes. T lymphocytes are essential to the immune response and without them, the body cannot fight infections or kill cancerous cells. Thus the weakened immune system allows opportunistic infections and neoplastic processes. The mechanism of CD4+ T cell depletion differs in the acute and chronic phases, to sum it all AIDS has a complex pathophysiology.[1]

Pathophysiology

HIV transmission

| Exposure Route | Estimated infections per 10,000 exposures to an infected source |

|---|---|

| Blood Transfusion | 9,000[3] |

| Childbirth | 2,500[4] |

| Needle-sharing injection drug use | 67[5] |

| Receptive anal intercourse¶ | 50[6][7] |

| Percutaneous needle stick | 30[8] |

| Receptive penile-vaginal intercourse¶ | 10[6][7][9] |

| Insertive anal intercourse¶ | 6.5[6][7] |

| Insertive penile-vaginal intercourse¶ | 5[6][7] |

| Receptive fellatio¶ | 1[7] |

| Insertive fellatio¶ | 0.5[7] |

| ¶ Assuming no condom use. | |

Since the beginning of the pandemic, three main transmission routes for HIV have been identified: sexual route, blood or blood product route, and mother-to-child transmission. Sexual route

- The majority of HIV infections are acquired through unprotected sexual relations. Sexual transmission can occur when infected sexual secretions of one partner come into contact with the genital, oral, or rectal mucous membranes of another.

Blood or blood product route

- This transmission route can account for infections in intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs and recipients of blood transfusions (though most transfusions are checked for HIV in the developed world) and blood products.

- It is also of concern for persons receiving medical care in regions where there is prevalent substandard hygiene in the use of injection equipment, such as the reuse of needles in Third World countries. HIV can also be spread through the sharing of needles.

- Health care workers such as nurses, laboratory workers, and doctors, have also been infected, although this occurs more rarely. People who give and receive tattoos, piercings, and scarification procedures can also be at risk of infection.

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT)

- The transmission of the virus from the mother to the child can occur in utero during pregnancy and intrapartum at childbirth. In the absence of treatment, the transmission rate between the mother and child is around 25%.[4] However, where combination antiretroviral drug treatment and Cesarian section are available, this risk can be reduced to as low as 1%.[4] Breast feeding also presents a risk of infection for the baby.

- HIV-2 is transmitted much less frequently by the MTCT and sexual route than HIV-1.

Other Considerations

- HIV has been found at low concentrations in the saliva, tears and urine of infected individuals, but there are no recorded cases of infection by these secretions and the potential risk of transmission is negligible.[10]

- The use of physical barriers such as the latex condom is widely advocated to reduce the sexual transmission of HIV. Spermicide, when used alone or with vaginal contraceptives like a diaphragm, actually increases the male to female transmission rate due to inflammation of the vagina; it should not be considered a barrier to infection.[11]

- A panel of experts convened by WHO and the UNAIDS Secretariat has "recommended that male circumcision now be recognized as an additional important intervention to reduce the risk of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men."[12]

- Research is clarifying whether there is a historical relationship between rates of male circumcision and rates of HIV in differing social and cultural contexts. Previously, Siegfried et al. suggested that it was possible that the correlation between circumcision and HIV in observational studies may be due to confounding factors, and remarked that the randomized controlled trials would therefore provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision.[13]

- There is little data on circumcision's effect on HIV risk with homosexual men and it is still being studied. A study of foreign and American men by scientists at the University of Washington, Seattle concluded: "Uncircumcised homosexual men in Seattle had a two fold increased risk of HIV infection.

- If the relative risk that we observed in Seattle were also present in other populations, the population attributable risk of uncircumcised status for HIV in homosexual men would be 40%, i.e., 40% of homosexual transmission of HIV could be potentially preventable with universal circumcision."[3]

- A study of Australian men headed by David Templeton, MD, from the University of New South Wales found "no relationship at all between circumcision and HIV seroconversion in" homosexual men. Templeton theorizes that this may be because most HIV occurs "following receptive rather than insertive intercourse," as he finds data on circumcision's effect on heterosexual men "compelling".[14] South African medical experts are concerned that the repeated use of unsterilized blades in the ritual (not medical) circumcision of adolescent boys may be spreading HIV.[15]

Immunopathogenesis

- The specific decline in CD44 helper T cells, result in inversion of the normal CD4/CD8 T cell ratio. It also cause dysregulation of B cell antibody production.[16][17]

- B cell exhibit increased expression of markers of activation and proliferation.[18] Terminal differentiation of B cell leads to increased immunoglobulin secretion, which further causes polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia producing non-specific antibodies.[19] This also explain the reason for increases risk of bacterial infection inspite of high circulating levels of immunoglobulins.

- The immune response to antigens begins to decline, as a result, the host fails to respond adequately to opportunistic infections and normally harmless commensals.

- The infections tend to be non-bacterial (i.e fungal, Viral) because the defect preferentially involves cellular immunity.

- Humoral immunity generally improves dramatically after the initiation of ART.

|

Role of GALT in Pathogenesis

- Port of entry for HIV infection is mostly through direct blood inoculation or exposure through genital mucosal surface. The gastrointestinal tract contains a large amount of lymphoid tissue, making it an ideal place for replication of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. GALT plays a role in HIV replication. [20]

- GALT has been found to have the following characteristics:

- Site of early viral seeding.

- Establishment of the pro-viral reservoir.

- The proviral GALT reservoir contributes to the following:

- Difficulty in controlling the infection.

- Difficulty in reducing the level of HIV provirus through sustained ART.[21] Various studies measuring the CD44 in GALT, have shown the relatively less reconstitution with ART, than that observed in peripheral blood.[22][23]

References

- ↑ Guss DA (1994). "The acquired immune deficiency syndrome: an overview for the emergency physician, Part 1". J Emerg Med. 12 (3): 375–84. PMID 8040596.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Smith, D. K., Grohskopf, L. A., Black, R. J., Auerbach, J. D., Veronese, F., Struble, K. A., Cheever, L., Johnson, M., Paxton, L. A., Onorato, I. A. and Greenberg, A. E. (2005). "Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection-Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV in the United States". MMWR. 54 (RR02): 1–20.

- ↑ Donegan, E., Stuart, M., Niland, J. C., Sacks, H. S., Azen, S. P., Dietrich, S. L., Faucett, C., Fletcher, M. A., Kleinman, S. H., Operskalski, E. A.; et al. (1990). "Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) among recipients of antibody-positive blood donations". Ann. Intern. Med. 113 (10): 733–739. PMID 2240875.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Coovadia, H. (2004). "Antiretroviral agents—how best to protect infants from HIV and save their mothers from AIDS". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (3): 289–292. PMID 15247337.

- ↑ Kaplan, E. H. and Heimer, R. (1995). "HIV incidence among New Haven needle exchange participants: updated estimates from syringe tracking and testing data". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 10 (2): 175–176. PMID 7552482.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV (1992). "Comparison of female to male and male to female transmission of HIV in 563 stable couples". BMJ. 304 (6830): 809–813. PMID 1392708.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Varghese, B., Maher, J. E., Peterman, T. A., Branson, B. M. and Steketee, R. W. (2002). "Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use". Sex. Transm. Dis. 29 (1): 38–43. PMID 11773877.

- ↑ Bell, D. M. (1997). "Occupational risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers: an overview". Am. J. Med. 102 (5B): 9–15. PMID 9845490.

- ↑ Leynaert, B., Downs, A. M. and de Vincenzi, I. (1998). "Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: variability of infectivity throughout the course of infection. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV". Am. J. Epidemiol. 148 (1): 88–96. PMID 9663408.

- ↑ Lifson AR (1988). "Do alternate modes for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus exist? A review". JAMA. 259 (9): 1353–6. PMID 2963151.

- ↑ "Should spermicides be used with condoms?". Condom Brochure, FDA OSHI HIV STDs. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ↑ WHO (2007). "WHO and UNAIDS announce recommendations from expert consultation on male circumcision for HIV prevention". WHO.int. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ↑ Siegfried, N., Muller, M., Deeks, J., Volmink, J., Egger, M., Low, N., Walker, S. and Williamson, P. (2005). "HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies". Lancet Infect. Dis. 5 (3): 165–173. PMID 15766651.

- ↑ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/560823

- ↑ Various (2005). "Repeated Use of Unsterilized Blades in Ritual Circumcision Might Contribute to HIV Spread in S. Africa, Doctors Say". Kaisernetwork.org. Retrieved 2006-03-28.

- ↑ Frazer IH, Mackay IR, Crapper RM, Jones B, Gust ID, Sarngadharan MG, Campbell DC, Ungar B (1986). "Immunological abnormalities in asymptomatic homosexual men: correlation with antibody to HTLV-III and sequential changes over two years". Q. J. Med. 61 (234): 921–33. PMID 3498182. Retrieved 2012-05-24. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Schechter MT, Boyko WJ, Craib KJ, McLeod A, Willoughby B, Douglas B, Constance P, O'Shaughnessey M (1987). "Effects of long-term seropositivity to human immunodeficiency virus in a cohort of homosexual men". AIDS. 1 (2): 77–82. PMID 2966631. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Moir S, Malaspina A, Pickeral OK, Donoghue ET, Vasquez J, Miller NJ, Krishnan SR, Planta MA, Turney JF, Justement JS, Kottilil S, Dybul M, Mican JM, Kovacs C, Chun TW, Birse CE, Fauci AS (2004). "Decreased survival of B cells of HIV-viremic patients mediated by altered expression of receptors of the TNF superfamily". J. Exp. Med. 200 (7): 587–99. PMID 15508184. Retrieved 2012-05-25. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Moir S, Malaspina A, Ogwaro KM, Donoghue ET, Hallahan CW, Ehler LA, Liu S, Adelsberger J, Lapointe R, Hwu P, Baseler M, Orenstein JM, Chun TW, Mican JA, Fauci AS (2001). "HIV-1 induces phenotypic and functional perturbations of B cells in chronically infected individuals". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (18): 10362–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.181347898. PMC 56966. PMID 11504927. Retrieved 2012-05-25. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Talal AH, Irwin CE, Dieterich DT, Yee H, Zhang L (2001). "Effect of HIV-1 infection on lymphocyte proliferation in gut-associated lymphoid tissue". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 26 (3): 208–17. PMID 11242193. Retrieved 2012-05-25. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Poles MA, Boscardin WJ, Elliott J, Taing P, Fuerst MM, McGowan I, Brown S, Anton PA (2006). "Lack of decay of HIV-1 in gut-associated lymphoid tissue reservoirs in maximally suppressed individuals". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 43 (1): 65–8. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000230524.71717.14. PMID 16936559. Retrieved 2012-05-25. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Guadalupe M, Reay E, Sankaran S, Prindiville T, Flamm J, McNeil A, Dandekar S (2003). "Severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy". J. Virol. 77 (21): 11708–17. PMC 229357. PMID 14557656. Retrieved 2012-05-25. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Shacklett BL, Cox CA, Sandberg JK, Stollman NH, Jacobson MA, Nixon DF (2003). "Trafficking of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD8+ T cells to gut-associated lymphoid tissue during chronic infection". J. Virol. 77 (10): 5621–31. PMC 154016. PMID 12719554. Retrieved 2012-05-25. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)

- Pages using citations with accessdate and no URL

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- HIV/AIDS

- Disease

- Immune system disorders

- Infectious disease

- Viral diseases

- Pandemics

- Sexually transmitted infections

- Syndromes

- Virology

- AIDS origin hypotheses

- Medical disasters

- Immunodeficiency

- Microbiology