|

|

| Line 11: |

Line 11: |

| ==Microscopic Pathology== | | ==Microscopic Pathology== |

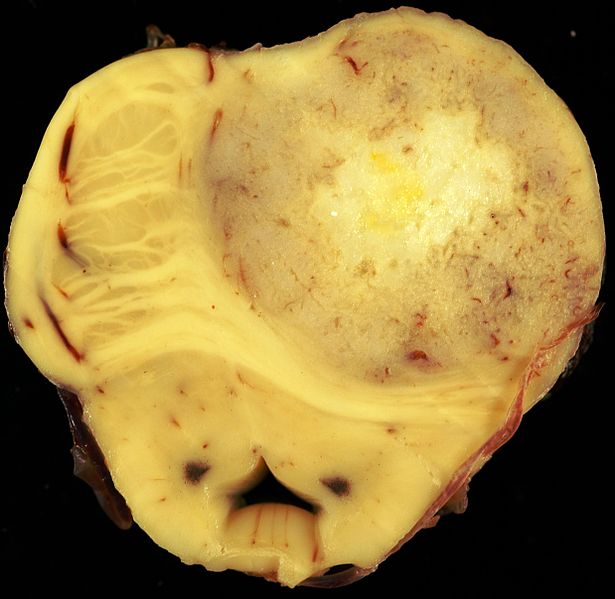

| * Histologic diagnosis with [[tissue]] [[biopsy]] will normally reveal an infiltrative character suggestive of the slow growing nature of the [[tumor]]. The tumor may be cavitating, [[pseudocyst]]-forming, or noncavitating. Appearance is usually white-gray, firm, and almost indistinguishable from normal white matter. | | * Histologic diagnosis with [[tissue]] [[biopsy]] will normally reveal an infiltrative character suggestive of the slow growing nature of the [[tumor]]. The tumor may be cavitating, [[pseudocyst]]-forming, or noncavitating. Appearance is usually white-gray, firm, and almost indistinguishable from normal white matter. |

|

| |

| ==Genetics==

| |

| ===Low-Grade Gliomas===

| |

| * Genomic alterations involving [[BRAF]] activation are very common in sporadic cases of pilocytic astrocytoma, resulting in activation of the [[ERK/MAPK]] pathway.

| |

| * [[BRAF]] activation in pilocytic astrocytoma occurs most commonly through a KIAA1549-[[BRAF]] [[gene]] fusion, producing a [[fusion protein]] that lacks the [[BRAF]] regulatory domain.<ref name="pmid18716556">{{cite journal| author=Bar EE, Lin A, Tihan T, Burger PC, Eberhart CG| title=Frequent gains at chromosome 7q34 involving BRAF in pilocytic astrocytoma. | journal=J Neuropathol Exp Neurol | year= 2008 | volume= 67 | issue= 9 | pages= 878-87 | pmid=18716556 | doi=10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181845622 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=18716556 }} </ref><ref name="pmid19373855">{{cite journal| author=Forshew T, Tatevossian RG, Lawson AR, Ma J, Neale G, Ogunkolade BW et al.| title=Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: a signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas. | journal=J Pathol | year= 2009 | volume= 218 | issue= 2 | pages= 172-81 | pmid=19373855 | doi=10.1002/path.2558 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=19373855 }} </ref><ref name="pmid18974108">{{cite journal| author=Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Bäcklund LM, Ichimura K et al.| title=Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. | journal=Cancer Res | year= 2008 | volume= 68 | issue= 21 | pages= 8673-7 | pmid=18974108 | doi=10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2097 | pmc=PMC2577184 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=18974108 }} </ref><ref name="pmid19363522">{{cite journal| author=Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Ichimura K, Collins VP| title=Oncogenic RAF1 rearrangement and a novel BRAF mutation as alternatives to KIAA1549:BRAF fusion in activating the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytoma. | journal=Oncogene | year= 2009 | volume= 28 | issue= 20 | pages= 2119-23 | pmid=19363522 | doi=10.1038/onc.2009.73 | pmc=PMC2685777 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=19363522 }} </ref> This fusion is seen in most infratentorial and midline pilocytic astrocytomas, but is present at lower frequency in supratentorial (hemispheric) [[tumor]]s.<ref name="pmid19543740">{{cite journal| author=Korshunov A, Meyer J, Capper D, Christians A, Remke M, Witt H et al.| title=Combined molecular analysis of BRAF and IDH1 distinguishes pilocytic astrocytoma from diffuse astrocytoma. | journal=Acta Neuropathol | year= 2009 | volume= 118 | issue= 3 | pages= 401-5 | pmid=19543740 | doi=10.1007/s00401-009-0550-z | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=19543740 }} </ref><ref name="pmid20044755">{{cite journal| author=Horbinski C, Hamilton RL, Nikiforov Y, Pollack IF| title=Association of molecular alterations, including BRAF, with biology and outcome in pilocytic astrocytomas. | journal=Acta Neuropathol | year= 2010 | volume= 119 | issue= 5 | pages= 641-9 | pmid=20044755 | doi=10.1007/s00401-009-0634-9 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20044755 }} </ref> <ref name="pmid19794125">{{cite journal| author=Yu J, Deshmukh H, Gutmann RJ, Emnett RJ, Rodriguez FJ, Watson MA et al.| title=Alterations of BRAF and HIPK2 loci predominate in sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma. | journal=Neurology | year= 2009 | volume= 73 | issue= 19 | pages= 1526-31 | pmid=19794125 | doi=10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c0664a | pmc=PMC2777068 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=19794125 }} </ref><ref name="pmid22157620">{{cite journal| author=Lin A, Rodriguez FJ, Karajannis MA, Williams SC, Legault G, Zagzag D et al.| title=BRAF alterations in primary glial and glioneuronal neoplasms of the central nervous system with identification of 2 novel KIAA1549:BRAF fusion variants. | journal=J Neuropathol Exp Neurol | year= 2012 | volume= 71 | issue= 1 | pages= 66-72 | pmid=22157620 | doi=10.1097/NEN.0b013e31823f2cb0 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22157620 }} </ref><ref name="pmid21610142">{{cite journal| author=Hawkins C, Walker E, Mohamed N, Zhang C, Jacob K, Shirinian M et al.| title=BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion predicts better clinical outcome in pediatric low-grade astrocytoma. | journal=Clin Cancer Res | year= 2011 | volume= 17 | issue= 14 | pages= 4790-8 | pmid=21610142 | doi=10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0034 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=21610142 }} </ref>

| |

| * Presence of the [[BRAF]]-KIAA1549 fusion predicted for better clinical outcome (progression-free survival [PFS] and overall survival) in one report that described children with incompletely resected low-grade [[glioma]]s.<ref name="pmid22492957">{{cite journal| author=Horbinski C, Nikiforova MN, Hagenkord JM, Hamilton RL, Pollack IF| title=Interplay among BRAF, p16, p53, and MIB1 in pediatric low-grade gliomas. | journal=Neuro Oncol | year= 2012 | volume= 14 | issue= 6 | pages= 777-89 | pmid=22492957 | doi=10.1093/neuonc/nos077 | pmc=PMC3367847 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22492957 }} </ref> However, other factors such as p16 [[deletion]] and [[tumor]] location may modify the impact of [[BRAF]] mutation on outcome. Progression to high-grade [[glioma]] is rare for pediatric low-grade [[glioma]] with the [[BRAF]]-KIAA1549 fusion. <ref name="pmid25667294">{{cite journal| author=Mistry M, Zhukova N, Merico D, Rakopoulos P, Krishnatry R, Shago M et al.| title=BRAF mutation and CDKN2A deletion define a clinically distinct subgroup of childhood secondary high-grade glioma. | journal=J Clin Oncol | year= 2015 | volume= 33 | issue= 9 | pages= 1015-22 | pmid=25667294 | doi=10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3922 | pmc=PMC4356711 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=25667294 }} </ref>

| |

| * [[BRAF]] activation through the KIAA1549-[[BRAF]] fusion has also been described in other pediatric low-grade [[glioma]]s (e.g.,pilomyxoid astrocytoma).

| |

| * Other genomic alterations in pilocytic astrocytomas that can also activate the [[ERK/MAPK]] pathway (e.g., alternative [[BRAF]] gene fusions, [[RAF1]] rearrangements, [[RAS]] mutations, and [[BRAF]] [[V600E]] point mutations) are less commonly observed.<ref name="pmid17712732">{{cite journal| author=Janzarik WG, Kratz CP, Loges NT, Olbrich H, Klein C, Schäfer T et al.| title=Further evidence for a somatic KRAS mutation in a pilocytic astrocytoma. | journal=Neuropediatrics | year= 2007 | volume= 38 | issue= 2 | pages= 61-3 | pmid=17712732 | doi=10.1055/s-2007-984451 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=17712732 }} </ref> BRAF V600E point mutations are observed in nonpilocytic pediatric low-grade [[glioma]]s as well, including approximately two-thirds of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma cases and in [[ganglioglioma]] and desmoplastic infantile [[ganglioglioma]]. One retrospective study of 53 children with gangliogliomas demonstrated [[BRAF V600E]] staining in approximately 40% of tumors. Five-year recurrence-free survival was worse in the [[V600E]]-mutated tumors (about 60%) than in the [[tumor]]s that did not stain for [[V600E]] (about 80%). The frequency of the [[BRAF V600E]] mutation was significantly higher in pediatric low-grade [[glioma]] that transformed to high-grade glioma (8 of 18 cases) than was the frequency of the mutation in cases that did not transform (10 of 167 cases).<ref name="pmid23609006">{{cite journal| author=Dahiya S, Haydon DH, Alvarado D, Gurnett CA, Gutmann DH, Leonard JR| title=BRAF(V600E) mutation is a negative prognosticator in pediatric ganglioglioma. | journal=Acta Neuropathol | year= 2013 | volume= 125 | issue= 6 | pages= 901-10 | pmid=23609006 | doi=10.1007/s00401-013-1120-y | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=23609006 }} </ref>

| |

| * As expected, given the role of NF1 deficiency in activating the [[ERK/MAPK]] pathway, activating [[BRAF]] genomic alterations are uncommon in pilocytic astrocytoma associated with [[NF1]].

| |

| * Activating mutations in [[FGFR1 and PTPN11]], as well as [[NTRK2]] fusion [[gene]]s, have also been identified in noncerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas. In pediatric grade II diffuse astrocytomas, the most common alterations reported are rearrangements in the MYB family of [[transcription]] factors in up to 53% of [[tumor]]s. <ref name="pmid23583981">{{cite journal| author=Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B et al.| title=Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. | journal=Nat Genet | year= 2013 | volume= 45 | issue= 6 | pages= 602-12 | pmid=23583981 | doi=10.1038/ng.2611 | pmc=PMC3727232 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=23583981 }} </ref>

| |

| * Most children with [[tuberous sclerosis]] have a mutation in one of two [[tuberous sclerosis]] genes (TSC1/[[hamartin]] or TSC2/[[tuberin]]). Either of these mutations results in an overexpression of the [[mTOR]] complex 1. These children are at risk of developing subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, in addition to cortical tubers and subependymal [[nodules]].

| |

|

| |

| ===High-Grade Astrocytomas===

| |

| * Pediatric high-grade gliomas, especially glioblastoma multiforme, are biologically distinct from those arising in adults.<ref name="pmid20479398">{{cite journal| author=Paugh BS, Qu C, Jones C, Liu Z, Adamowicz-Brice M, Zhang J et al.| title=Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. | journal=J Clin Oncol | year= 2010 | volume= 28 | issue= 18 | pages= 3061-8 | pmid=20479398 | doi=10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7252 | pmc=PMC2903336 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20479398 }} </ref><ref name="pmid20570930">{{cite journal| author=Bax DA, Mackay A, Little SE, Carvalho D, Viana-Pereira M, Tamber N et al.| title=A distinct spectrum of copy number aberrations in pediatric high-grade gliomas. | journal=Clin Cancer Res | year= 2010 | volume= 16 | issue= 13 | pages= 3368-77 | pmid=20570930 | doi=10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0438 | pmc=PMC2896553 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20570930 }} </ref><ref name="pmid20052518">{{cite journal| author=Ward SJ, Karakoula K, Phipps KP, Harkness W, Hayward R, Thompson D et al.| title=Cytogenetic analysis of paediatric astrocytoma using comparative genomic hybridisation and fluorescence in-situ hybridisation. | journal=J Neurooncol | year= 2010 | volume= 98 | issue= 3 | pages= 305-18 | pmid=20052518 | doi=10.1007/s11060-009-0081-4 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20052518 }} </ref><ref name="pmid20725730">{{cite journal| author=Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Sobol RW, Nikiforova MN, Lyons-Weiler MA, LaFramboise WA et al.| title=IDH1 mutations are common in malignant gliomas arising in adolescents: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. | journal=Childs Nerv Syst | year= 2011 | volume= 27 | issue= 1 | pages= 87-94 | pmid=20725730 | doi=10.1007/s00381-010-1264-1 | pmc=PMC3014378 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20725730 }} </ref> Pediatric high-grade gliomas, compared with adult [[tumor]]s, less frequently have PTEN and EGFRgenomic alterations, and more frequently have PDGF/PDGFR genomic alterations and mutations in [[histone]] H3.3genes. Although it was believed that pediatric glioblastoma multiforme tumors were more closely related to adult secondary glioblastoma multiforme tumors in which there is stepwise transformation from lower-grade into higher-grade gliomas and in which most tumors have IDH1 and IDH2 mutations, the latter mutations are rarely observed in childhood glioblastoma multiforme tumors.<ref name="pmid22286061">{{cite journal| author=Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K et al.| title=Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. | journal=Nature | year= 2012 | volume= 482 | issue= 7384 | pages= 226-31 | pmid=22286061 | doi=10.1038/nature10833 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22286061 }} </ref><ref name="pmid22286216">{{cite journal| author=Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J et al.| title=Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. | journal=Nat Genet | year= 2012 | volume= 44 | issue= 3 | pages= 251-3 | pmid=22286216 | doi=10.1038/ng.1102 | pmc=PMC3288377 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22286216 }} </ref>

| |

| * Based on epigenetic patterns (DNA methylation), pediatric glioblastoma multiforme tumors are separated into relatively distinct subgroups with distinctive [[chromosome]] copy number gains/losses and gene mutations.<ref name="pmid23079654">{{cite journal| author=Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C et al.| title=Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. | journal=Cancer Cell | year= 2012 | volume= 22 | issue= 4 | pages= 425-37 | pmid=23079654 | doi=10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=23079654 }} </ref>

| |

| * Two subgroups have identifiable recurrent H3F3A mutations, suggesting disrupted epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, with one subgroup having mutations at K27 ([[lysine]] 27) and the other group having mutations at G34 ([[glycine]] 34). The subgroups are the following:

| |

| * H3F3A [[mutation]] at K27: The K27 cluster occurs predominately in mid-childhood (median age, approximately 10 years), is mainly midline ([[thalamus]], [[brainstem]], and [[spinal cord]]), and carries a very poor [[prognosis]]. These tumors also frequently have TP53 mutations. Thalamic high-grade gliomas in older adolescents and young adults also show a high rate of H3F3A K27 [[mutation]]s.

| |

| * H3F3A mutation at G34: The second H3F3A mutation tumor cluster, the G34 grouping, is found in somewhat older children and young adults (median age, 18 years), arises exclusively in the [[cerebral cortex]], and carries a somewhat better prognosis. The G34 clusters also have [[TP53]] [[mutation]]s and widespread [[hypomethylation]] across the whole [[genome]].

| |

| * The H3F3A K27 and G34 mutations appear to be unique to high-grade gliomas and have not been observed in other pediatric [[brain]] tumors.<ref name="pmid23429371">{{cite journal| author=Gielen GH, Gessi M, Hammes J, Kramm CM, Waha A, Pietsch T| title=H3F3A K27M mutation in pediatric CNS tumors: a marker for diffuse high-grade astrocytomas. | journal=Am J Clin Pathol | year= 2013 | volume= 139 | issue= 3 | pages= 345-9 | pmid=23429371 | doi=10.1309/AJCPABOHBC33FVMO | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=23429371 }} </ref> Both mutations induce distinctive DNA methylation patterns compared with the patterns observed in IDH-mutated tumors, which occur in young adults.<ref name="pmid22661320">{{cite journal| author=Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM, Bouffet E et al.| title=K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. | journal=Acta Neuropathol | year= 2012 | volume= 124 | issue= 3 | pages= 439-47 | pmid=22661320 | doi=10.1007/s00401-012-0998-0 | pmc=PMC3422615 | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22661320 }} </ref>

| |

| * Other pediatric glioblastoma multiforme subgroups include the RTK PDGFRA and mesenchymal clusters, both of which occur over a wide age range, affecting both children and adults. The RTK PDGFRA and mesenchymal subtypes are comprised predominantly of cortical tumors, with cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme tumors being rarely observed; they both carry a poor prognosis.

| |

| * Childhood secondary high-grade [[glioma]] (high-grade [[glioma]] that is preceded by a low-grade [[glioma]]) is uncommon (2.9% in a study of 886 patients). No pediatric low-grade [[glioma]]s with the BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion transformed to a high-grade glioma, whereas low-grade gliomas with the BRAF V600E mutations were associated with increased risk of transformation. Approximately 40% of patients (7 of 18) with secondary high-grade [[glioma]] had BRAF [[V600E]] mutations, with CDKN2A alterations present in 57% of cases (8 of 14).

| |

|

| |

|

| ==Histopathological Video== | | ==Histopathological Video== |