Alzheimer's disease medical therapy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Medical Therapy== | ==Medical Therapy== | ||

Currently-used treatments offer a small symptomatic benefit. No treatments to halt the progression of the disease are yet available. | |||

===Pharmacotherapies=== | ===Pharmacotherapies=== | ||

Revision as of 16:15, 16 August 2012

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

|

Alzheimer's disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Alzheimer's disease medical therapy On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Alzheimer's disease medical therapy |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Alzheimer's disease medical therapy |

Overview

There is no known cure for Alzheimer's disease. Available treatments offer relatively small symptomatic benefit but remain palliative in nature. Current treatments can be divided into pharmaceutical, psychosocial and caregiving.

Medical Therapy

Currently-used treatments offer a small symptomatic benefit. No treatments to halt the progression of the disease are yet available.

Pharmacotherapies

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) currently approve four medications to treat the cognitive manifestations of AD. Three are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the other is memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist. No drug is currently able to delay or halt the progression of the disease.

Because reduction in cholinergic neuronal activity is well known in Alzheimer's disease,[1] acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are employed to reduce the rate at which acetylcholine (ACh) is broken down. This increases the concentration of ACh in the brain, thereby combatting the loss of ACh caused by the death of the cholinergic neurons.[2] Cholinesterase inhibitors currently approved include donepezil (brand name Aricept),[3] galantamine (Razadyne),[4] and rivastigmine (branded as Exelon,[5] and Exelon Patch[6]). There is also evidence for the efficacy of these medications in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease,[7] and some evidence for their use in the advanced stage. Only donepezil is approved for treatment of advanced AD dementia.[8] The use of these drugs in mild cognitive impairment has not shown any effect in delaying the onset of AD.[9] The most common side effects include nausea and vomiting, both of which are linked to cholinergic excess. These side effects arise in approximately ten to twenty percent of users and are mild to moderate in severity. Less common secondary effects include muscle cramps; decreased heart rate (bradycardia), decreased appetite and weight, and increased gastric acid.[10][11][12][13]

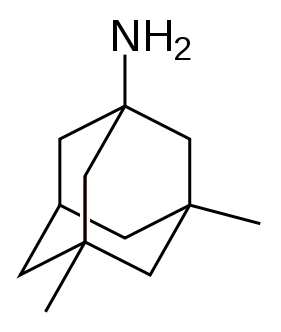

Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter of the nervous system. Excessive amounts of glutamate in the brain can lead to cell death through a process called excitotoxicity which consists of the overstimulation of glutamate receptors. Excitotoxicity occurs not only in Alzheimer's disease, but also in other neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis.[14] Memantine (brand names Akatinol, Axura, Ebixa/Abixa, Memox and Namenda),[15] is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist first used as an anti-influenza agent. It acts on the glutamatergic system by blocking NMDA glutamate receptors and inhibits their overstimulation by glutamate.[14] Memantine has been shown to be moderately efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Its effects in the initial stages of AD are unknown.[16] Reported adverse events with memantine are infrequent and mild, including hallucinations, confusion, dizziness, headache and fatigue.[17] Memantine used in combination with donepezil has been shown to be "of statistically significant but clinically marginal effectiveness".[18]

Neuroleptic anti-psychotic drugs commonly given to Alzheimer's patients with behavioural problems are modestly useful in reducing aggression and psychosis, but are associated with serious adverse effects, such as cerebrovascular events, movement difficulties or cognitive decline. These side effects do not permit the routine use of these medications.[19][20][21]

Psychosocial intervention

Psychosocial interventions are used as an adjunct to pharmaceutical treatment and can be classified within behavior, emotion, cognition or stimulation oriented approaches. Research on efficacy is unavailable and rarely specific to Alzheimer's disease, focusing instead on dementia as a whole.[22]

Behavioral interventions attempt to identify and reduce the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors. This approach has not shown success in the overall functioning of patients,[23] but can help to reduce some specific problem behaviors, such as incontinence.[24] There is still a lack of high quality data on the effectiveness of these techniques in other behavior problems such as wandering.[25][26]

Emotion-oriented interventions include reminiscence therapy, validation therapy, supportive psychotherapy, sensory integration or snoezelen, and simulated presence therapy. Supportive psychotherapy has received little or no formal scientific study, but some clinicians find it useful in helping mildly impaired patients adjust to their illness.[22] Reminiscence therapy (RT) involves the discussion of past experiences individually or in group, often with the aid of photographs, household items, music and sound recordings, or other familiar items from the past. Although there are few quality studies on the effectiveness of RT it may be beneficial for cognition and mood.[27] Simulated presence therapy (SPT) is based on attachment theories and is normally carried out playing a recording with voices of the closest relatives of the patient. There is preliminary evidence indicating that SPT may reduce anxiety and challenging behaviors.[28][29] Finally, validation therapy is based on acceptance of the reality and personal truth of another's experience, while sensory integration is based on exercises aimed to stimulate senses. There is little evidence to support the usefulness of these therapies.[30][31]

The aim of cognition-oriented treatments, which include reality orientation and cognitive retraining is the restoration of cognitive deficits. Reality orientation consists of the presentation of information about time, place or person in order to ease the the patient's understanding of their surroundings. On the other hand, cognitive retraining tries to improve impaired capacities by exercising mental abilities. Both have shown some efficacy improving cognitive capacities,[32][33] although in some works these effects were transient. Negative effects, such as frustration, have also been reported.[22]

Stimulation-oriented treatments include art, music and pet therapies, exercise, and any other kind of recreational activities for patients. Stimulation has modest support for improving behavior, mood, and, to a lesser extent, function. Nevertheless, as important as these effects are, the main support for the use of stimulation therapies is the improvement in the patient's daily life, as opposed to improving the underlying disease course.[22]

Caregiving

Since there is no cure for Alzheimer's, caregiving is an essential part of the treatment. Due to the eventual inability for the sufferer to self-care, Alzheimer's has to be carefully care-managed. Home care in the familiar surroundings of home may delay onset of some symptoms and delay or eliminate the need for more professional and costly levels of care.[34] Many family members choose to look after their relative,[35] but two-thirds of nursing home residents have dementias.[36]

Modifications to the living environment and lifestyle of the Alzheimer's patient can improve functional performance and ease caretaker burden. Assessment by an occupational therapist is often indicated. Adherence to simplified routines and labeling of household items to cue the patient can aid with activities of daily living, while placing safety locks on cabinets, doors, and gates and securing hazardous chemicals can prevent accidents and wandering. Changes in routine or environment can trigger or exacerbate agitation, whereas well-lit rooms, adequate rest, and avoidance of excess stimulation all help prevent such episodes.[37][38] Appropriate social and visual stimulation can improve function by increasing awareness and orientation. For instance, boldly colored tableware aids those with severe AD, helping people overcome a diminished sensitivity to visual contrast to increase food and beverage intake.[39]

References

- ↑ Geula C, Mesulam MM (1995). "Cholinesterases and the pathology of Alzheimer disease". Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 9 Suppl 2: 23–8. PMID 8534419.

- ↑ Stahl SM (2000). "The new cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease, Part 2: illustrating their mechanisms of action". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (11): 813–814. PMID 11105732.

- ↑ "Donepezil". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "Galantamine". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "Rivastigmine". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "Rivastigmine Transdermal". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ Birks J (2006). "Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD005593. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005593. PMID 16437532.

- ↑ Birks J, Harvey RJ (2006). "Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001190. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001190.pub2. PMID 16437430.

- ↑ Raschetti R, Albanese E, Vanacore N, Maggini M (2007). "Cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of randomised trials". PLoS Med. 4 (11): e338. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040338. PMID 18044984.

- ↑ "Aricept and Aricept ODT Product Insert" (PDF). Eisai and Pfizer. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ "Razadyne ER U.S. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Ortho-McNeil Neurologics. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "Exelon ER U.S. Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "Exelon U.S. Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lipton SA (2006). "Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: memantine and beyond". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 5 (2): 160–170. doi:10.1038/nrd1958. PMID 16424917.

- ↑ "Memantine". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2004-01-04. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Areosa Sastre A, McShane R, Sherriff F (2004). "Memantine for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub2. PMID 15495043.

- ↑ "Namenda Prescribing Information" (PDF). Forest Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A; et al. (2008). "Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline". Annals of Internal Medicine. 148 (5): 379–397. PMID 18316756.

- ↑ Ballard C, Waite J (2006). "The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2. PMID 16437455.

- ↑ Ballard C, Lana MM, Theodoulou M; et al. (2008). "A Randomised, Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Dementia Patients Continuing or Stopping Neuroleptics (The DART-AD Trial)". PLoS Med. 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050076. PMID 18384230.

- ↑ Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K (2005). "Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence". JAMA. 293 (5): 596–608. doi:10.1001/jama.293.5.596. PMID 15687315.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's disease and Other Dementias" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. October 2007. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423967.152139. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Bottino CM, Carvalho IA, Alvarez AM; et al. (2005). "Cognitive rehabilitation combined with drug treatment in Alzheimer's disease patients: a pilot study". Clin Rehabil. 19 (8): 861–869. doi:10.1191/0269215505cr911oa. PMID 16323385.

- ↑ Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck C; et al. (2001). "Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 56 (9): 1154–1166. PMID 11342679.

- ↑ Hermans DG, Htay UH, McShane R (2007). "Non-pharmacological interventions for wandering of people with dementia in the domestic setting". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD005994. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005994.pub2. PMID 17253573.

- ↑ Robinson L, Hutchings D, Dickinson HO; et al. (2007). "Effectiveness and acceptability of non-pharmacological interventions to reduce wandering in dementia: a systematic review". Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 22 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1002/gps.1643. PMID 17096455.

- ↑ Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, Orrell M, Davies S (2005). "Reminiscence therapy for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001120. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub2. PMID 15846613.

- ↑ Peak JS, Cheston RI (2002). "Using simulated presence therapy with people with dementia". Aging Ment Health. 6 (1): 77–81. doi:10.1080/13607860120101095. PMID 11827626.

- ↑ Camberg L, Woods P, Ooi WL; et al. (1999). "Evaluation of Simulated Presence: a personalised approach to enhance well-being in persons with Alzheimer's disease". J Am Geriatr Soc. 47 (4): 446–452. PMID 10203120.

- ↑ Neal M, Briggs M (2003). "Validation therapy for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001394. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001394. PMID 12917907.

- ↑ Chung JC, Lai CK, Chung PM, French HP (2002). "Snoezelen for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003152. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003152. PMID 12519587.

- ↑ Spector A, Orrell M, Davies S, Woods B (2000). "WITHDRAWN: Reality orientation for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001119. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001119.pub2. PMID 17636652.

- ↑ Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B; et al. (2003). "Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial". Br J Psychiatry. 183: 248–254. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.3.248. PMID 12948999.

- ↑ Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Newcomer R (2005). "Early community-based service utilization and its effects on institutionalization in dementia caregiving". Gerontologist. 45 (2): 177–85. PMID 15799982. Retrieved 2008-05-30. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C, Lyketsos C, Livingston G (2007). "Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia". Journal of Affective Disorders. 101 (1–3): 75–89. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.025. PMID 17173977. Retrieved 2012-08-16. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's disease and Other Dementias" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. October 2007. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423967.152139. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ "Treating behavioral and psychiatric symptoms". Alzheimer's Association. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- ↑ Wenger GC, Burholt V, Scott A (1998). "Dementia and help with household tasks: a comparison of cases and non-cases". Health Place. 4 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/S1353-8292(97)00024-5. PMID 10671009.

- ↑ Dunne TE, Neargarder SA, Cipolloni PB, Cronin-Golomb A (2004). "Visual contrast enhances food and liquid intake in advanced Alzheimer's disease". Clinical Nutrition. 23 (4): 533–538. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2003.09.015. PMID 15297089.