Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty of a Left Main Chronic Total Occlusion in a Retrograde Approach via a Saphenous Vein Graft with Impella Support

Click here to go back to the Tweetbook

Click here to read more about chronic total occlusion

Click here to read more about impella

Authors

Jonathan S. Gordin, MD (@JonGordin)1; Ravi H. Dave, MD (@RaviDaveMD1)2; William M. Suh, MD (@willsuh76)2

1From Division of Cardiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA

Case

Thoracic radiation is an important element in the treatment of various malignancies including Hodgkin’s lymphoma and breast cancer [1]. While this has improved survival, it can cause multiple cardiovascular complications in the decades to follow, including accelerated calcification [2], valvular dysfunction [3], and accelerated coronary artery atherosclerosis [4] leading to an increased rate of early myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death. Computed tomography (CT) studies have shown that recipients of mantle irradiation have a greater extent of multi-vessel coronary artery disease and plaques in the proximal portion of the vessels [5] and often require revascularization via coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery at a young age. Unfortunately, the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) often lays within the field of radiation and may be unusable due to radiation injury or fibrosis [6] and even when grafted, shows a long-term patency similar to that of venous conduits [7]. This combination of accelerated coronary disease, early life CABG, poor vascular conduits, valvular dysfunction, extensive aortic calcification, and increased surgical risk raise the possibility of complex percutaneous coronary interventions in this patient population. In this case report, we present the case of a 49-year old woman with a history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and mantle radiation with prior CABG presenting with recurrent, daily angina and dyspnea on exertion.

The patient was diagnosed and treated for Hodgkin’s lymphoma twenty years prior to current presentation and underwent chemotherapy and mantle radiation. Eleven years after remission, she began to experience angina. Subsequent coronary angiogram demonstrated multivessel coronary artery disease; 95% left main stenosis involving the ostial left anterior descending (LAD), and moderate obtuse marginal (OM) stenosis in a left dominant system with mild aortic stenosis. She underwent CABG with saphenous vein grafts (SVG) to the LAD, OM, and posterior descending artery (PDA). The LIMA was a poor conduit because it was atretic, likely from prior radiation therapy. At the time of surgery, additional radiation effects were noted, including the fusing of the pericardium to the posterior sternum and she underwent a pericardiectomy. Her recovery was uneventful and she had complete resolution of symptoms.

Seven years after her CABG, the patient again experienced angina and dyspnea on exertion. Echocardiogram revealed severe aortic stenosis and coronary angiogram demonstrated flush occlusion of the left main coronary artery and occlusion of the SVG to the LAD. The SVG to the OM was patent and provided brisk flow to the circumflex which filled the entire LAD from retrograde flow with a proximal 50% circumflex stenosis and a 70% ostial LAD stenosis (Figure 1). The SVG to the PDA was also patent. She was evaluated by the Heart Team and although her STS PROM of 3.9% placed her at intermediate risk for redo CABG and surgical aortic valve replacement, she was considered extreme risk due to prior chest radiation. She was referred for PCI and TAVR.

The first PCI attempt was tried left #RadialFirst but was unsuccessful due to inability to engage a guiding catheter in the SVG to OM. After switching to a #SafeFemoral approach, a 6F Modified TIG guide (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) provided reasonable support. Attempts to pass a 0.014” coronary wire were initially unsuccessful due to the acute angle at the distal anastomosis. Using a guide extension catheter and OTW balloon for support, we were able to advance a wire retrograde up to the origin of the left circumflex (LCX). We were unable to cross from LCX to LAD due to acute angulation. In addition, the combination of the OTW balloon and wire passing through the distal anastomosis caused a kink which compromised the flow into the left dominant system (Figure 2). The patient experienced significant chest pressure and became hemodynamically unstable and so all the equipment was withdrawn from the graft with resolution of symptoms. The procedure was aborted.

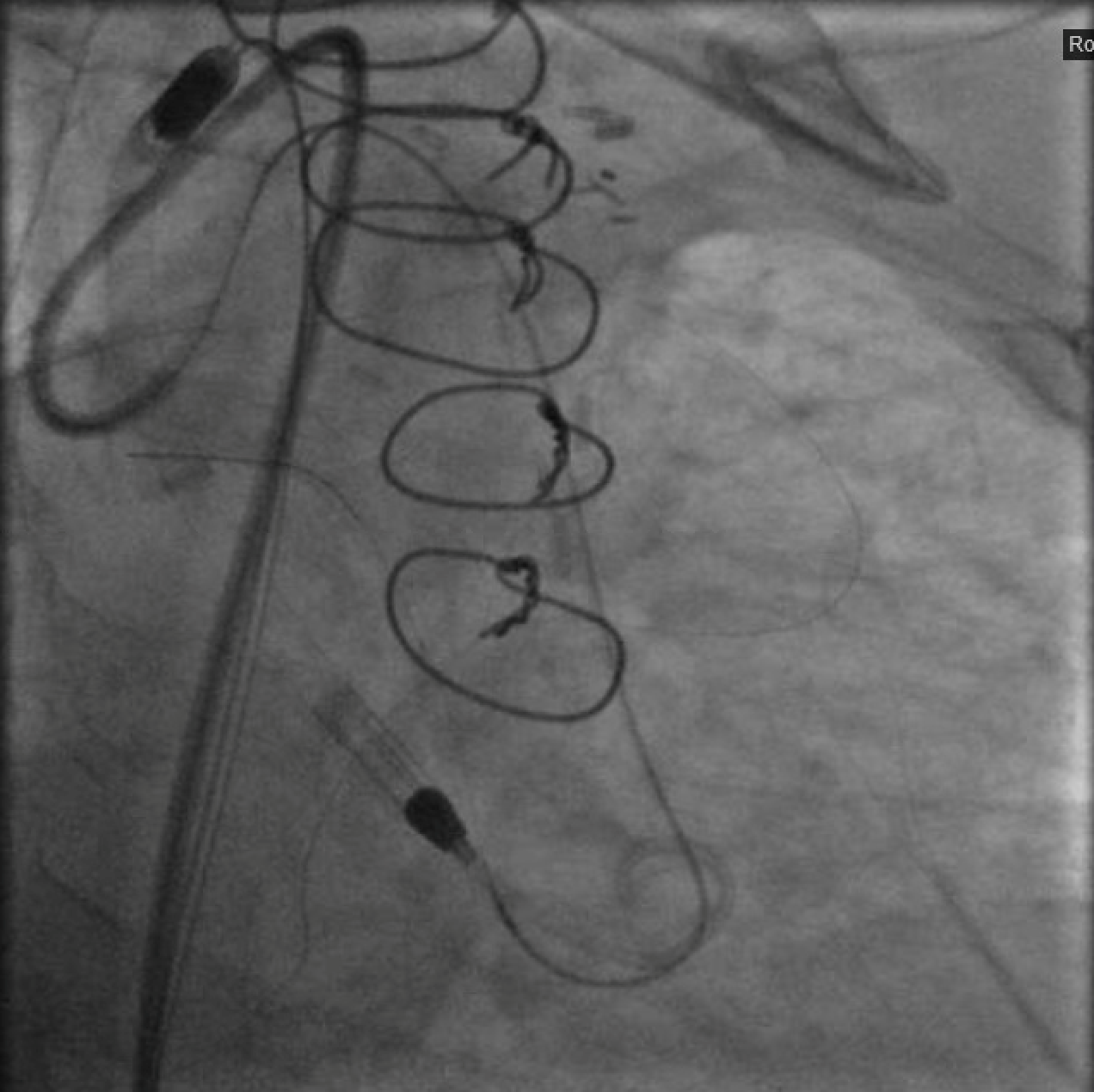

After again reviewing treatment options with the patient, we brought her back for a second attempt with #ProtectedPCI. From the left femoral artery an Impella CP (Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA) ventricular assist device was placed into the left ventricle. The SVG was engaged with an 8F AL1 guide (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). After multiple attempts with a variety of wires, we eventually were able to get a Fielder XT with a Corsair microcatheter (Asahi Intecc, Aichi, Japan) to pass into the proximal portion of the LCX. Again, the flow from the SVG to the OM became compromised and hemodynamics worsened, however the output from the Impella CP and vasoactive support from an epinephrine drip maintained adequate perfusion. The Fielder XT was exchanged for a Pilot 200 which successfully navigated through the left main CTO and into the ascending aorta (Figure 3, Video 1). Once the wire crossed, the Corsair was withdrawn proximal to the distal anastomosis, improving flow through the graft into the OM. We attempted to externalize the wire into a guide from a right radial approach but this was unsuccessful. We therefore dilated the left main with a 3.5mm balloon (Figure 4) via the SVG guide. Afterwards, we carefully removed the AL1 guide from the vein graft, leaving the Pilot 200 wire in place. We then advanced a 6F Judkins Left (JL) 3 guide (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to engage the left main and advanced a Runthrough wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) antegrade through the newly created channel in the left main and into the distal circumflex artery. We removed the Pilot 200 wire entirely having secured an antegrade wire and advanced a Fielder XT into the distal LAD (Figure 5). We then proceeded to stent the LM extending into the LAD with a 3.5mm x 24mm Synergy drug-eluting stent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). Left main stent was post-dilated to 4.0 mm. An additional 3.0mm x 24mm Synergy stent was placed in the proximal LAD to seal a distal edge dissection, after which there was brisk antegrade flow from the left main through the entire LAD (Figure 6). The ostium of the circumflex experienced plaque shift and there was little antegrade flow, however the entire system was supplied by the vein graft. At the end of the case, we were able to remove the Impella CP and seal all arteriotomies. She was immediately extubated and after overnight observation was discharged from the hospital.

At follow-up two weeks later, she noted completed resolution of her angina with persistent dyspnea on exertion. Four weeks from the initial intervention, she underwent TAVR via a transfemoral approach with a 23mm SAPIEN 3 (Edwards Lifesciences, Irving, CA, USA) valve. She was discharged after overnight observation and at her one month post TAVR follow-up she denied any symptoms of angina or dyspnea.

Figures

-

Video 1. Injection of SVG to OM graft with retrograde filling of the entire circumflex system which then provides antegrade flow into the LAD. Stenosis seen both in the proximal circumflex and ostial LAD.

-

Video 2. A wire in the ostial circumflex supported by an OTW balloon and a guide extension catheter. Note the kink just proximal to the anatamosis of the SVG to the OM and poor flow in the distal LAD.

-

Video 3. Crossing the left main CTO from the retrograde approach with a Pilot 200 wire supported by a Corsair microcatheter (currently being withdrawn).

-

Figure 1. Injection of SVG to OM graft with retrograde filling of the entire circumflex system which then provides antegrade flow into the LAD. Stenosis seen both in the proximal circumflex and ostial LAD.

-

Figure 2. A wire in the ostial circumflex supported by an OTW balloon and a guide extension catheter. Note the kink just proximal to the anatamosis of the SVG to the OM and poor flow in the distal LAD.

-

Figure 3. Crossing the left main CTO from the retrograde approach with a Pilot 200 wire supported by a Corsair microcatheter (currently being withdrawn).

-

Figure 4. : Inflating a 3.5mm balloon in the left main CTO to create a channel for antegrade access. The guide in the ascending aorta will not engage the left main despite repeated efforts from a radial approach.

-

Figure 5. An 8F JL3 guide has engaged the left main from a femoral approach and a Runthrough wire is now in the posterior lateral branch and a Fielder XT is in the distal LAD. The guide engaging the vein graft and the retrograde Pilot 200 have been removed.

-

Figure 6. Final cranial view of LAD. TIMI 3 antegrade flow into the LAD with reduced flow into the circumflex.

Comments

To our knowledge, this is the first report of opening a CTO of the left main via a retrograde approach from a vein graft. This case is also noteworthy in that the utility of the Impella CP was clearly demonstrated since the first PCI attempt had to be aborted due to ischemic compromise causing hemodynamic instability whereas the second PCI attempt was tolerated and successful because hemodynamic support was implemented.

References

- ↑ Jaworski C, Mariani JA, Wheeler G, Kaye DM (2013). "Cardiac complications of thoracic irradiation". J Am Coll Cardiol. 61 (23): 2319–28. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.090. PMID 23583253.

- ↑ Apter S, Shemesh J, Raanani P, Portnoy O, Thaler M, Zissin R; et al. (2006). "Cardiovascular calcifications after radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma: computed tomography detection and clinical correlation". Coron Artery Dis. 17 (2): 145–51. PMID 16474233.

- ↑ Heidenreich PA, Hancock SL, Lee BK, Mariscal CS, Schnittger I (2003). "Asymptomatic cardiac disease following mediastinal irradiation". J Am Coll Cardiol. 42 (4): 743–9. PMID 12932613.

- ↑ Hull MC, Morris CG, Pepine CJ, Mendenhall NP (2003). "Valvular dysfunction and carotid, subclavian, and coronary artery disease in survivors of hodgkin lymphoma treated with radiation therapy". JAMA. 290 (21): 2831–7. doi:10.1001/jama.290.21.2831. PMID 14657067.

- ↑ van Rosendael AR, Daniëls LA, Dimitriu-Leen AC, Smit JM, van Rosendael PJ, Schalij MJ; et al. (2017). "Different manifestation of irradiation induced coronary artery disease detected with coronary computed tomography compared with matched non-irradiated controls". Radiother Oncol. 125 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2017.09.008. PMID 28987749.

- ↑ Hicks GL (1992). "Coronary artery operation in radiation-associated atherosclerosis: long-term follow-up". Ann Thorac Surg. 53 (4): 670–4. PMID 1554280.

- ↑ Brown ML, Schaff HV, Sundt TM (2008). "Conduit choice for coronary artery bypass grafting after mediastinal radiation". J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 136 (5): 1167–71. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.005. PMID 19026798.