Neurofibromatosis type II

| Neurofibromatosis type II | |

| ICD-10 | D33 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 237.72 |

| OMIM | 101000 |

| DiseasesDB | 8960 |

| MeSH | D016518 |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Neurofibromatosis Type II (or "MISME Syndrome", for "Multiple Inherited Schwannomas, Meningiomas, and Ependymomas") is an inherited disease. The main manifestation of the disease is the development of symmetric, non-malignant brain tumours in the region of the cranial nerve VIII, which is the auditory-vestibular nerve that transmits sensory information from the inner ear to the brain. Most people with this condition also experience problems in their eyes. NF II is caused by mutations of the "Merlin" gene, which, it seems, influences the form and movement of cells. The principal treatments consist of neurosurgical removal of the tumors and surgical treatment of the eye lesions. There is no therapy for the underlying disorder of cell function caused by the genetic mutation.

Causes

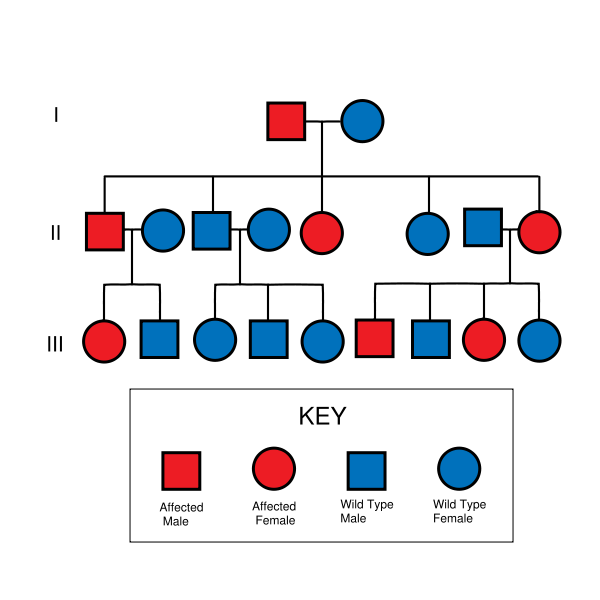

Incidence, Mode of transmission, Epidemiology

NF II is an inheritable disorder with an autosomal dominant mode of transmission. Incidence of the disease is about 1 in 40,000. There is a broad clinical spectrum known, but all patients checked have been found to have some mutation of the same gene on chromosome 22. Through statistics, it is suspected that one-half of cases are inherited, and one-half are the result of new, de novo mutations.

Pathogenesis, Molecular Biology and pathophysiological relations

NF II is caused by a defect in the gene that normally gives rise to a product called Merlin or Schwannomin, located on chromosome 22 band q11-13.1. This peptide is thought to have a tumor-suppressive function. In a normal cell, the concentrations of active (dephosphorylated) merlin are controlled by processes such as cell adhesion (which would indicate the need to restrain cell division). It is known that Merlin's deficiency can result in unmediated progression through the cell cycle due to the lack of contact-mediated tumour suppression, sufficient to result in the tumors characteristic of Neurofibromatosis type II. The NF II gene is presumed to result in either a failure to synthesize Merlin or the production of a defective peptide that lacks the normal tumor-suppressive effect. The Schwannomin-peptide consists of 595 amino acids. Comparison of Schwannomin with other proteins shows similarities to proteins that connect the cytoskeleton to the cell membrane. Mutations in the Schwannomin-gene are thought to alter the movement and shape of affected cells with loss of contact inhibition.

Pathology

The so-called acoustic neuroma of NF II is, in fact, a Schwannoma of the nervus vestibularis. The wrong term is used, despite better knowledge in the whole scientific and medical literature. The vestibular Schwannomas grow slowly at the inner entrance of the internal auditory meatus (meatus acousticus internus). They derive from the nerve sheaths of the upper part of the nervus vestibularis in the region between the central and peripheral myelin (Obersteiner-Redlich-Zone) within the area of the porus acousticus, 1 cm from the brainstem.

Genotype-Phenotype-Correlation

Many patients with NF II were included in studies that were designed to compare disease type and progression with exact determination of the associated mutation. The goal of such comparisons of genotype and phenotype is to determine whether specific mutations cause respective combinations of symptoms. This would be extremely valuable for the prediction of disease progression and the planning of therapy starting at a young age. The results of such studies are the following:

- In most cases the mutation in the NF II gene causes shortened peptides.

- There are no mutational hot-spots.

- Patients with Frameshift mutation- or Nonsense mutations suffer poor prognosis.

- Patients with Missense mutations have a better prognosis.

- In cases with Mutations in the splice-acceptor-region, there is no good correlation to determine.

- Point mutations may have only minor effects.

- Cases are published in which exactly the same mutation is associated with clearly different outcome.

These results suggest, that probably other factors (Environment, other mutations) will determine the clinical outcome.

Symptoms and Signs

The clinical spectrum of the disease is broad. In other words, people with NF II may develop a wide range of distinct problems.

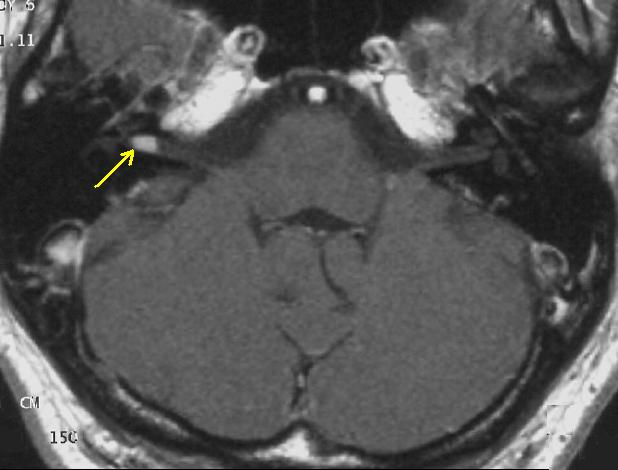

- Acoustic nerve: 90% of the patients show bilateral acoustic neuromas on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Other cranial nerves and meninges: About 50% of patients develop tumours in other cranial nerves or Meningiomas.

- Spinal cord: About 50% of the patients develop spinal lesions. Only 40% of the spinal lesions are symptomatic. The spinal tumours in NF II are separated in two groups. Intramedullary lesions are located within the spinal tissue and usually belong to the so-called spinal astrocytomas or ependymomas. The extramedullary lesions are located within the small space between the surface of the spinal cord and the bony wall of the spinal canal. These tumours belong to the Schwannomas and Meningiomas.

- Skin: If children show neurofibromas, a diagnostic procedure should be performed to decide which form of neurofibromatosis causes the alterations.

- Eyes: Studies on patients with NF II showed that more than 90% of the affected persons suffer eye lesions. The most common alteration in NF II is the juvenile subcapsular cataract (opacity of the lens) in young people.

"Presenting symptoms" (initial concern that brings a patient to a doctor) of a lesion of the nervus vestibulocochlearis due to a tumour in the region of the cerebello-pontine angle are the following: hearing loss (98%), tinnitus (70%), dysequilibrium (67%), headache (32%), facial numbness and weakness (29% and 10% respectively).

"Clinical signs" (alterations that are not regarded by the patient and that can be detected by the doctor in a clinical examination) of the lesion in discussion are: abnormal corneal reflex (33%), nystagmus (26%), facial hypesthesia (26%).

Evaluation (study of the patient with technical methods) shows the enlargement of the porus acousticus internus in the CT scan, enhancing tumours in the region of the cerebello-pontine angle in gadolinium-enhanced MRI scans, hearing loss in audiometric studies and perhaps pathological findings in Electronystagmography. Some times there are elevated levels of protein in liquor study.

Diagnosis

The "cardinal symptom" of the disease is bilateral acoustic neurinoma. (By its cardinal symptom a disorder is defined.)

The term "diagnostic criteria" designates the combination of symptoms enabling the doctor to ascertain the diagnosis of the respective disease. In the case of NF II the diagnostic criteria are the following:

- Detection of bilateral acoustic neurinoma by imaging-procedures

- First degree relative with NF II and the occurrence of Neurofibroma, Meningiomas, Glioma, or Schwannoma

- First degree relative with NF II and the occurrence of juvenile posterior subcapsular cataract.

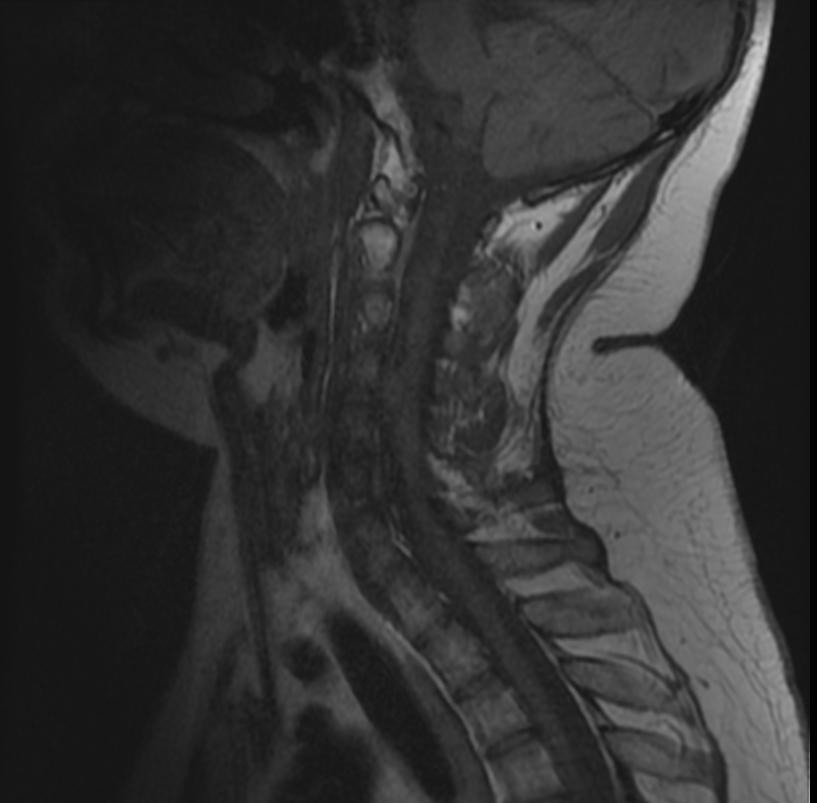

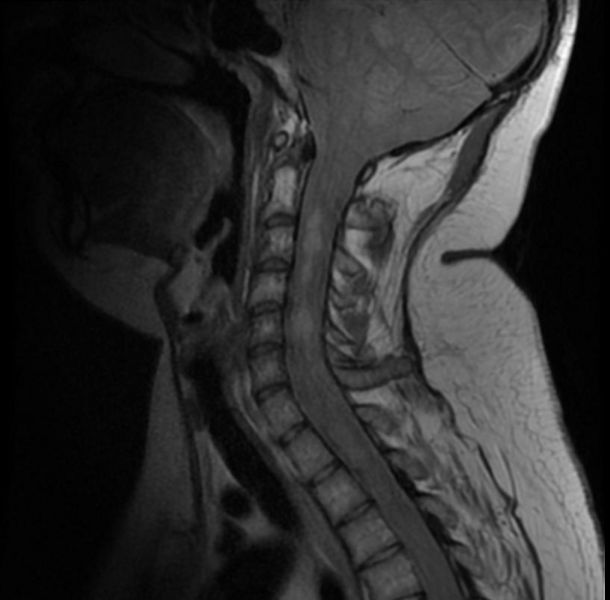

MR images demonstrate multiple ependymomas is this patient with NF2

Progression of the Disease

In NF II Acoustic neuromas usually affect young people, whereas, in sporadic forms of Acoustic neuromas, the appearance of the tumour is limited to the elderly.

There are two forms of the NF II:

- The Wishart-Phenotype is characterized by multiple cerebral and spinal lesions in patients younger than 20 years and with rapid progression of the tumours.

- Patients that develop single central tumours with slow progression after age of 20 are thought to have the Feiling-Gardner-Phenotype.

Treatment

Therapy

Early diagnosis allows better planning of therapy in young patients with NF II. In many cases, the hearing loss is present for 10 years before the correct diagnosis is established. Early in the disease, surgery for an acoustic neurinoma can protect facial nerve function in many patients. In selected cases of patients with very small tumors and good bilateral hearing, surgery may offer the possibility of long-term hearing preservation.

Patients with the Wishard phenotype suffer multiple reccurrences of the tumour after surgical treatment. In the case of facial nerve palsy, the muscles of the eyelids can lose their mobility, leading to conjunctivitis and corneal injury. "Lidloading" (implantation of small magnets, gold weights, or springs in the lid) can help prevent these complications. Other means of preserving corneal health include tarsorrhaphy, where the eyelids are partially sewn together to narrow the opening of the eye, or the use of punctal plugs, which block the duct that drains tears from the conjunctival sac. All these techniques conserve moisture from the lacrymal glands, which lubricates the cornea and prevents injury. Most patients with NF II develop cataracts, which often require replacement of the lens. Children of affected parents should have a specialist examination every year to detect developing tumors. Learning of sign-language is one means of preparation for those that will most probably suffer complete hearing loss.

Operative therapy of acoustic neuroma

There are six different surgical techniques for the removal of acoustic neuroma. Three are only rarely used. The choice of approach is determined by size of the tumour, hearing capability, and general clinical condition of the patient.

- The retrosigmoid (also known as the suboccipital) approach offers some opportunity for the retention of hearing, but is known to have more complications.

- The translabyrinthine approach will sacrifice hearing on that side, but will usually spare the facial nerve. Post-OP CSF leaks are more common.

- The middle fossa approach is preferred for small tumours, and offers the highest probability of retention of hearing and vestibular function.

- Less invasive endoscopic techniques have been done outside of the United States for some time. Only in the last ten years has Endoscopy been used for Tumor resection in the U.S. Recovery times are reported to be faster, and smaller scars are present. There are many political reasons why endoscopy is not mainstream yet within the surgeon community. With time, endoscopy may be the primary mode of AN removals. There are surgeons within the U.S. that do these groundbreaking less-invasive surgical techniques for many surgeries, not just AN resection. Many have been the scorn of traditional surgeons that are not familiar with the technology or techniques.

Larger tumors can be treated by either the translabyrinthine approach or the retrosigmoid approach, depending upon the experience of the surgical team. With large tumors, the chance of hearing preservation is small, even with the retrosigmoid approach. When hearing is already poor, the translabyrinthine approach may be used for even small tumors. Small, lateralized tumours in patients with good hearing should have the middle fossa approach. When the location of the tumour is more medial a retrosigmoid approach may be better.

Another surgical technique can prolong usable hearing when a vestibular schwannoma has grown too large to remove without damage to the cochlear nerve. In the IAC (internal auditory canal) decompression, a middle fossa approach is employed to expose the bony roof of the IAC without any attempt to remove the tumor. The bone overlying the acoustic nerve is removed, allowing the tumour to expand upward into the middle cranial fossa. In this way, pressure on the cochlear nerve is relieved, reducing the risk of further hearing loss from direct compression or obstruction of vascular supply to the nerve.

Radiosurgery is a conservative alternative to cranial base or other intracranial surgery. With conformal radiosurgical techniques, therapeutic radiation focused on the tumour, sparing exposure to surrounding normal tissues. Although radiosurgery can seldom completely destroy a tumor, it can often arrest its growth or reduce its size. While radiation is less immediately damaging than conventional surgery, it incurs a higher risk of subsequent malignant change in the irradiated tissues, and this risk in higher in NF2 than in sporadic (non-NF2) lesions.

Management of Hearing Loss in NF2

Because hearing loss in those with NF2 almost always occurs after acquisition of verbal language skills, patients do not always integrate well into the Deaf culture and are more likely to resort to auditory assistive technology. The most sophisticated of these devices is the cochlear implant, which can sometimes restore a high level of auditory function even when natural hearing is totally lost. However, the amount of destruction to the cochlear nerve caused by the typical NF2 schwannoma often precludes the use of such an implant. In these cases, an auditory brainstem implant (ABI) can restore a primitive level of hearing, which, when supplemented by lip reading, can restore a functional understanding of spoken language.

References

Books

- Raymond D. Adams (Ed.): Principles of Neurology. McGraw-Hill. New York 1997. ISBN 0-07-067439-6.

- Bruce O. Berg (Ed.): Principles of Child Neurology. McGraw-Hill. New York 1996. ISBN 0-07-005193-3.

- Mark S. Greenberg: Handbook of Neurosurgery. Lakeland 1997. ISBN 0-9626384-5-5.

- Andrew H. Kaye and Edward R. Laws Jr (Ed.): Brain Tumors. An Encyclopedic Approach. Churchill Livingston. Edinburgh 1995. ISBN 0-443-04840-1.

- Olaf Rieß und Ludger Schöls (Hrsg.): Neurogenetik. Molekulargenetische Diagnostik neurologischer Erkrankungen. Springer. Berlin 1998. ISBN 3-540-63874-1.

- Lewis P. Rowland (Ed.): Merrits Textbook of Neurology. Williams and Wilkins. Baltimore 1995. ISBN 0-683-07400-8.

- T. Strachan und A.P. Read (Ed.): Human Molecular Genetics. BIOS Scientific Publishers Limited. 1996. ISBN 3-8274-0039-2.

Articles

- Baser ME, Mautner VF, Ragge NK; et al. (1996). "Presymptomatic diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 2 using linked genetic markers, neuroimaging, and ocular examinations". Neurology. 47 (5): 1269–77. PMID 8909442.

- Evans DG, Huson SM, Donnai D; et al. (1992). "A genetic study of type 2 neurofibromatosis in the United Kingdom. I. Prevalence, mutation rate, fitness, and confirmation of maternal transmission effect on severity". J. Med. Genet. 29 (12): 841–6. PMID 1479598.

- Evans DG, Huson SM, Donnai D; et al. (1992). "A clinical study of type 2 neurofibromatosis". Q. J. Med. 84 (304): 603–18. PMID 1484939.

- Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Freidlin V, Datiles MB; et al. (1989). "The association of posterior capsular lens opacities with bilateral acoustic neuromas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2". Arch. Ophthalmol. 107 (4): 541–4. PMID 2705922.

- Kluwe L, Bayer S, Baser ME; et al. (1996). "Identification of NF2 germ-line mutations and comparison with neurofibromatosis 2 phenotypes". Hum. Genet. 98 (5): 534–8. PMID 8882871.

- MacCollin M, Ramesh V, Jacoby LB; et al. (1994). "Mutational analysis of patients with neurofibromatosis 2". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 55 (2): 314–20. PMID 7913580.

- Mautner VF, Tatagiba M, Guthoff R, Samii M, Pulst SM (1993). "Neurofibromatosis 2 in the pediatric age group". Neurosurgery. 33 (1): 92–6. PMID 8355853.

- Mautner VF, Tatagiba M, Lindenau M; et al. (1995). "Spinal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: MR imaging study of frequency, multiplicity, and variety". AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 165 (4): 951–5. PMID 7676998.

- Mautner VF, Lindenau M, Baser ME; et al. (1996). "The neuroimaging and clinical spectrum of neurofibromatosis 2". Neurosurgery. 38 (5): 880–5, discussion 885–6. PMID 8727812.

- Mérel P, Hoang-Xuan K, Sanson M; et al. (1995). "Screening for germ-line mutations in the NF2 gene". Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 12 (2): 117–27. PMID 7535084.

- Parry DM, Eldridge R, Kaiser-Kupfer MI; et al. (1994). "Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2): clinical characteristics of 63 affected individuals and clinical evidence for heterogeneity". Am. J. Med. Genet. 52 (4): 450–61. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320520411. PMID 7747758.

- Rouleau GA, Wertelecki W, Haines JL; et al. (1987). "Genetic linkage of bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis to a DNA marker on chromosome 22". Nature. 329 (6136): 246–8. doi:10.1038/329246a0. PMID 2888021.

- Rouleau GA, Merel P, Lutchman M; et al. (1993). "Alteration in a new gene encoding a putative membrane-organizing protein causes neuro-fibromatosis type 2". Nature. 363 (6429): 515–21. doi:10.1038/363515a0. PMID 8379998.

- Sainz J, Figueroa K, Baser ME, Mautner VF, Pulst SM (1995). "High frequency of nonsense mutations in the NF2 gene caused by C to T transitions in five CGA codons". Hum. Mol. Genet. 4 (1): 137–9. PMID 7711726.

- Trofatter JA, MacCollin MM, Rutter JL; et al. (1993). "A novel moesin-, ezrin-, radixin-like gene is a candidate for the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor". Cell. 72 (5): 791–800. PMID 8453669.

See also

External links

- General: http://www.neuroguide.com/

- Society for Neuroscience

- Description of surgical management: Acoustic Neuroma Patient Archive

- Research/Advocacy: Advocure

- Information about auditory brainstem implants: House Ear Institute

- Research/Advocacy: Children's Tumor Foundation: Ending Neurofibromatosis Through ResearchWebsite