Cleft lip and palate pathophysiology

|

Cleft lip and palate Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cleft lip and palate pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cleft lip and palate pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Cleft lip and palate pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Pathophysiology

Cleft lip

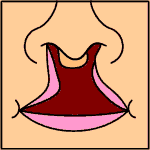

If only skin tissue is affected one speaks of cleft lip. Cleft lip is formed in the top of the lip as either a small gap or an indentation in the lip (partial or incomplete cleft) or continues into the nose (complete cleft). Lip cleft can occur as one sided (unilateral) or two sided (bilateral). It is due to the failure of fusion of the maxillary and medial nasal processes (formation of the primary palate).

-

Unilateral incomplete

-

Unilateral complete

-

Bilateral complete

A mild form of a cleft lip is a microform cleft. A microform cleft can appear as small as a little dent in the red part of the lip or look like a scar from the lip up to the nostril. In some cases muscle tissue in the lip underneath the scar is affected and might require reconstructive surgery. It is advised to have newborn infants with a microform cleft checked with a craniofacial team as soon as possible to determine the severeness of the cleft. The actor Joaquin Phoenix is an example of a person with a microform cleft that did not require surgery.

Cleft palate

Cleft palate is a condition in which the two plates of the skull that form the hard palate (roof of the mouth) are not completely joined. The soft palate is in these cases cleft as well. In most cases, cleft lip is also present. Cleft palate occurs in about one in 700 live births worldwide.[1]

Palate cleft can occur as complete (soft and hard palate, possibly including a gap in the jaw) or incomplete (a 'hole' in the roof of the mouth, usually as a cleft soft palate). When cleft palate occurs, the uvula is usually split.It occurs due to the failure of fusion of the lateral palatine processes, the nasal septum, and/or the median palatine processes (formation of the secondary palate).

The hole in the roof of the mouth caused by a cleft connects the mouth directly to the nasal cavity.

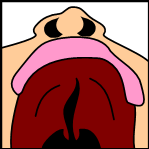

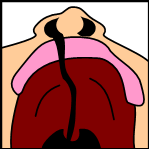

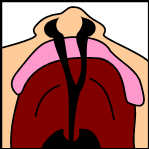

Note: the next images show the roof of the mouth. The top shows the nose, the lips are colored pink. For clarity the images depict a toothless infant.

-

Incomplete cleft palate

-

Unilateral complete lip and palate

-

Bilateral complete lip and palate

A direct result of an open connection between the oral cavity and nasal cavity is velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI).

During the first six to eight weeks of pregnancy, the shape of the embryo's head is formed. Five primitive tissue lobes grow:

- a) one from the top of the head down towards the future upper lip;

- b-c) two from the cheeks, which meet the first lobe to form the upper lip;

- d-e) and just below, two additional lobes grow from each side, which form the chin and lower lip;

If these tissues fail to meet, a gap appears where the tissues should have joined (fused). This may happen in any single joining site, or simultaneously in several or all of them. The resulting birth defect reflects the locations and severity of individual fusion failures (e.g., from a small lip or palate fissure up to a completely malformed face).

The upper lip is formed earlier than the palate, from the first three lobes named a to c above. Formation of the palate is the last step in joining the five embryonic facial lobes, and involves the back portions of the lobes b and c. These back portions are called palatal shelves, which grow towards each other until they fuse in the middle.[2] This process is very vulnerable to multiple toxic substances, environmental pollutants, and nutritional imbalance. The biologic mechanisms of mutual recognition of the two shelves, and the way they are glued together, are quite complex and obscure despite intensive scientific research.[3]

References

- ↑ "Statistics by country for cleft palate". WrongDiagnosis.com. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Dudas et al. (2007): Palatal fusion – Where do the midline cells go? A review on cleft palate, a major human birth defect. Acta Histochemica, Volume 109, Issue 1, 1 March 2007,1-14

- ↑ Dudas M, Li WY, Kim J, Yang A, Kaartinen V (2007). "Palatal fusion -where do the midline cells go? A review on cleft palate, a major human birth defect". Acta Histochem. 109 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2006.05.009. PMID 16962647.