Zika virus infection pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

(Category) |

m (Bot: Removing from Primary care) |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

[[Category:Disease]] | [[Category:Disease]] | ||

[[Category:Emergency mdicine]] | |||

[[Category:Up-To-Date]] | [[Category:Up-To-Date]] | ||

[[Category:Infectious disease]] | [[Category:Infectious disease]] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:46, 30 July 2020

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oGNxGlltnOs%7C350}} |

|

Zika virus infection Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Zika virus infection pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Zika virus infection pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Zika virus infection pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Yazan Daaboul, M.D., Nate Michalak, B.A., Serge Korjian M.D., Yamuna Kondapally, M.B.B.S[2]

Overview

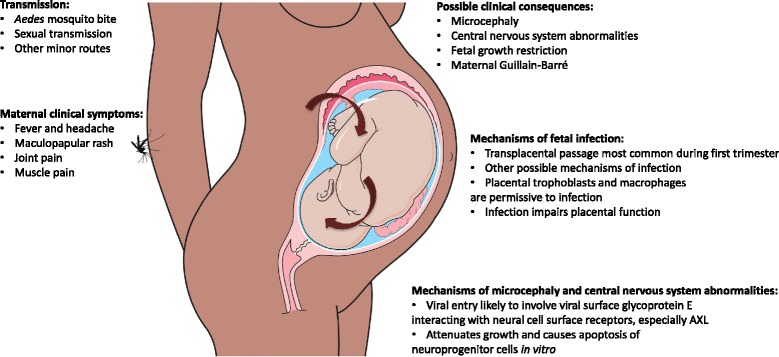

Zika virus is a vector-borne pathogen transmitted via the Aedes mosquito, which also transmits the dengue and chikungunya viruses. Human-to-human transmission by sexual intercourse has been confirmed. Zika virus is thought to initially replicate in dendritic cells near the site of inoculation before spreading to lymph nodes and then the bloodstream.

Pathophysiology

Transmission

Through mosquito bites

Zika virus is primarily transmitted to humans via the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito. These mosquitoes are also vectors for dengue and chikungunya viruses.[1][2]

From mother to child

- Infected pregnant women can transmit the Zika virus during the pregnancy or around the time of birth.[2]

- Intrauterine

- Perinatal

- Prolonged circulation of ZIKV RNA is demonstrated in serum of pregnant women.[3][4]

- There are no reports of infants acquiring Zika virus through breastfeeding. Due to the nutritional benefits of breastmilk, mothers are encouraged to breastfeed even in areas where Zika virus is endemic.

Sexual transmission

Zika virus has also been suspected to be sexually transmitted between humans.

- Asymptomatic males to their female partners

- Symptomatic female to her male partner

- Symptomatic or asymptomatic males to males

- Longer shedding of Zika virus is detected in semen

- The maximum documented time of Zika virus RNA detection in semen after onset of symptoms is 188 days (potentially for up to 6 months)

- Zika virus has been detected for up to 11 days in vaginal fluid[5]

Blood transfusion

- Transmission through blood transfusion is possible (very likely but not confirmed) as Zika virus has been identified in asymptomatic donors during an ongoing outbreak.[2][6][7][8]

- In non-pregnant individuals, the viremia with ZIKV may produce 8.1 million copies/ml in serum, which can last for 1-2 weeks.[9][10][11]

- Whole blood has a longer period of viremia than serum.

- ZIKV has been detected in whole blood as late as 58 days after onset of symptoms.[12]

Laboratory exposure

- There has been one reported laboratory-acquired Zika virus disease in United States.[2]

Pathogenesis

- Mosquito-borne Zika virus is thought to initially replicate in dendritic cells near the site of inoculation before spreading to lymph nodes and then the bloodstream.

- One study indicates that Zika virus replicates in cellular nuclei, as opposed to other flaviviruses that do so in the cytoplasm.[13]

- Virus is detectable in blood with in 3 to 4 days of symptom onset.

- The virus can be detected in blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, amniotic fluid, semen, and saliva.

- The maximum documented time of Zika virus RNA detection in semen after onset of symptoms is 188 days.

- Once a person has been infected with Zika, they are likely to be protected from future infections.

- Zika virus can be killed by potassium permanganate, ether, temperatures >60°C, but is not effectively neutralized by 10% ethanol.[1]

Fetus

- The exact pathogenesis of Zika virus infection in the fetus is not fully understood.[14]

- The crucial period for brain development is the first trimester of pregnancy. ZIKV infection during this period is more strongly associated with microcephaly than infections later in the pregnancy.

- Based on in vitro investigational studies, Zika virus infects the human embryonic cortical neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) which lead to disruption of cell cycle, increased cell death (via caspase-3-mediated apoptosis), and gene dysregulation resulting in cortical thinning and microcephaly.[15]

- Infected hNPCs also produce infectious Zika particles.

-

Zika pathogenesis - Source: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-016-0660-0

{{#ev:youtube|PpswPzFh5TI}}

Gross pathology

On gross pathology, the characteristic findings of Zika virus infection in neonates include:[16][17]

- Microcephaly

- Widespread brain calcifications in the cortex and sub-cortical white matter

- Ventricular enlargement secondary to cerebral atrophy

Associated Conditions

- There was a significant increase in patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome and congenital microcephaly during the 2014 Zika virus outbreak in French Polynesia and the 2015 Zika virus outbreak in Brazil.

- According to WHO, ZIKV infection during pregnancy is the cause of congenital brain abnormalities including microcephaly.[18]

- Current evidence does not show which specific environmental and host factors interact with Zika virus to increase the risk of an affected pregnancy or of GBS or whether there are specific factors that also have an effect in certain places.[18]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hayes EB (2009). "Zika virus outside Africa". Emerg Infect Dis. 15 (9): 1347–50. doi:10.3201/eid1509.090442. PMC 2819875. PMID 19788800.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Zika Virus Transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (June 1, 2015). http://www.cdc.gov/zika/transmission/index.html Accessed on December 17, 2015

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Blood/UCM518213.pdf

- ↑ Meaney-Delman D, Oduyebo T, Polen KN, White JL, Bingham AM, Slavinski SA; et al. (2016). "Prolonged Detection of Zika Virus RNA in Pregnant Women". Obstet Gynecol. 128 (4): 724–30. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001625. PMID 27479770.

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Blood/UCM518213.pdf

- ↑ Musso D, Nhan T, Robin E, Roche C, Bierlaire D, Zisou K; et al. (2014). "Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014". Euro Surveill. 19 (14). PMID 24739982.

- ↑ Motta IJ, Spencer BR, Cordeiro da Silva SG, Arruda MB, Dobbin JA, Gonzaga YB; et al. (2016). "Evidence for Transmission of Zika Virus by Platelet Transfusion". N Engl J Med. 375 (11): 1101–3. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1607262. PMID 27532622.

- ↑ Barjas-Castro ML, Angerami RN, Cunha MS, Suzuki A, Nogueira JS, Rocco IM; et al. (2016). "Probable transfusion-transmitted Zika virus in Brazil". Transfusion. 56 (7): 1684–8. doi:10.1111/trf.13681. PMID 27329551.

- ↑ Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Powers AM, Honein MA (2016). "Zika Virus". N Engl J Med. 374 (16): 1552–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1602113. PMID 27028561.

- ↑ Anderson KB, Thomas SJ, Endy TP (2016). "The Emergence of Zika Virus: A Narrative Review". Ann Intern Med. 165 (3): 175–83. doi:10.7326/M16-0617. PMID 27135717.

- ↑ Zika infection http://www.who.int/bulletin/online_first/16-174540.pdf(April, 2016) Accessed on September 27, 2016

- ↑ Lustig Y, Mendelson E, Paran N, Melamed S, Schwartz E (2016). "Detection of Zika virus RNA in whole blood of imported Zika virus disease cases up to 2 months after symptom onset, Israel, December 2015 to April 2016". Euro Surveill. 21 (26). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.26.30269. PMID 27386894.

- ↑ Buckley A, Gould EA (1988). "Detection of virus-specific antigen in the nuclei or nucleoli of cells infected with Zika or Langat virus". J Gen Virol. 69 ( Pt 8): 1913–20. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-69-8-1913. PMID 2841406.

- ↑ Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, Wen Z, Qian X, Li Y, Yao B, Shin J, Zhang F, Lee EM, Christian KM, Didier RA, Jin P, Song H, Ming GL (2016). "Zika Virus Infects Human Cortical Neural Progenitors and Attenuates Their Growth". Cell Stem Cell. 18 (5): 587–90. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016. PMID 26952870.

- ↑ Boeuf P, Drummer HE, Richards JS, Scoullar MJ, Beeson JG (2016). "The global threat of Zika virus to pregnancy: epidemiology, clinical perspectives, mechanisms, and impact". BMC Med. 14 (1): 112. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0660-0. PMC 4973112. PMID 27487767.

- ↑ Sampathkumar P, Sanchez JL (2016). "Zika Virus in the Americas: A Review for Clinicians". Mayo Clin. Proc. 91 (4): 514–21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.017. PMID 27046524.

- ↑ Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popović M, Poljšak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, Kolenc M, Resman Rus K, Vesnaver Vipotnik T, Fabjan Vodušek V, Vizjak A, Pižem J, Petrovec M, Avšič Županc T (2016). "Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly". N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (10): 951–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. PMID 26862926.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 WHO Zika causality statement http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/causality/en/