Relapsing fever

For patient information click here

| Relapsing fever | |

| ICD-10 | A68 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 087 |

| DiseasesDB | 1547 |

| eMedicine | emerg/590 med/1999 |

| MeSH | D012061 |

|

Relapsing fever Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Relapsing fever On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Relapsing fever |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Historical Perspective

Pathophysiology

Epidemiology & Demographics

Risk Factors

Screening

Causes

Differentiating Relapsing fever

Complications & Prognosis

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms | Physical Examination | Laboratory tests | Electrocardiogram | X Rays | CT | MRI Echocardiography or Ultrasound | Other images | Alternative diagnostics

Treatment

Medical therapy | Surgical options | Primary prevention | Secondary prevention | Financial costs | Future therapies

Overview

Relapsing fever is an infection caused by certain bacteria in the genus Borrelia.[1] It is a vector-borne disease that is transmitted through louse or soft-bodied tick bites.[2]

Epidemiology and Demographics

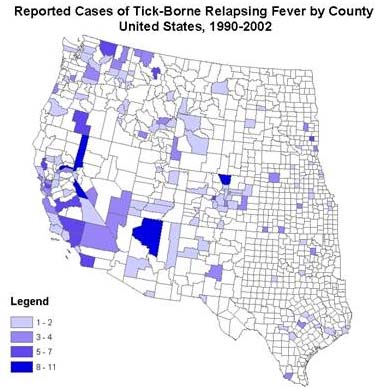

TBRF is endemic in the western US, southern British Columbia, plateau regions of Mexico, Central and South America, the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and much of Africa. The first endemic focus of TBRF in the US was identified in 1915 in Colorado (Meader 1915) though the first case was actually in 1905 in New York in a traveler to Texas. Since then, TBRF has been reported in 14 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Most recent cases and outbreaks have occurred in rustic cabin or vacation home settings at higher elevations (> 8,000 feet) in coniferous forests in the western US (Banerjee, Banerjee et al. 1998; Trevejo, Schriefer et al. 1998; Paul, Maupin et al. 2002; Centers for Disease and Prevention 2003; Schwan, Policastro et al. 2003).

TBRF normally occurs in summer months when people are traveling to mountainous areas on vacation. TBRF can, however, occur in winter, particularly when people go into rodent infested cabins and start fires, warming the cabin and producing carbon dioxide and warmth that attract the ticks that transmit TBRF.

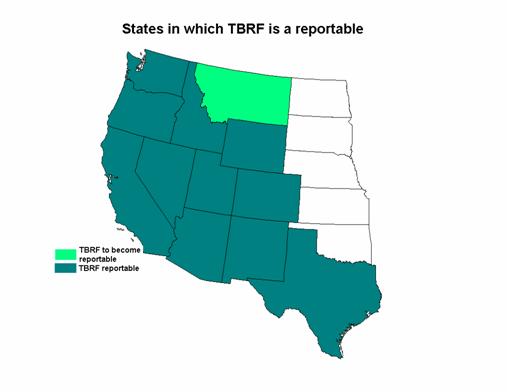

Reporting of TBRF

Although TBRF was removed from the list of nationally notifiable conditions in 1987, 11 states require TBRF to be reported to their State Health Departments (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). Other states such as Montana, may institute reporting in the future. [3]

Risk Factors

TBRF in pregnancy

TBRF contacted during pregnancy can cause spontaneous abortion, [[premature birth, and neonatal death (Melkert and Stel 1991). The maternal-fetal transmission of Borrelia is believed to occur either transplacentally (Steenbarger 1982) or while traversing the birth canal. In one study, perinatal infection with TBRF was shown to lead to lower birth weights, younger gestational age, and higher perinatal mortality (Jongen, van Roosmalen et al. 1997).

In general, pregnant women have higher spirochete loads and more severe symptoms than nonpregnant women. Higher spirochete loads have not, however, been found to correlate with fetal outcome.

Immunity

Although there is limited information on the immunity of TBRF, there have been patients who developed the disease more than once.[4]

Infection

In the United States, TBRF is caused by one of three Borrelia species: B. hermsii, B. parkerii, and B. turicatae. Most human illness is caused by B. hermsii.

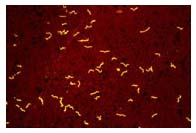

The relapsing fever Borrelia spp are gram negative helical bacteria normally 0.2 to 0.5 microns in width and 5 to 20 microns in length. They are visible with light microscopy and have the cork-screw shape typical of all spirochetes (see picture). They have a unique process of DNA rearrangement in their linear DNA. Each time the DNA is read a different antigenic marker, also known as a variable major protein, is created, which allows the organism to evade the immune system and therefore cause recurrent patterns of fever and other symptoms.

Borrelia is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. Soft ticks (family Argasidae) differ in many ways from the so-called hard ticks (family Ixodidae), including the more familiar dog tick and deer tick.

In contrast to hard ticks, soft ticks take brief blood meals lasting less than a half hour, usually at night. Between meals the ticks live in the nesting materials in their host burrows. Individual ticks will take many such blood meal during each stage of their life cycles, including the development of eggs by adult females. The bites of soft ticks are usually painless and the persons who are bitten while asleep are usually unaware that they were bitten.

The individual Borrelia species that cause TBRF are usually associated with specific tick vectors. For instance, B. hermsii is transmitted to humans by O. hermsi ticks, while B. parkerii is transmitted by O. parkeri and B. turicatae is transmitted by O. turicata. Each tick has a preferred environment and preferred set of hosts. O. hermsi tends to be found at higher altitudes (1500 – 8000 feet) where it is associated primarily with ground or tree squirrels and chipmunks. O. parkeri occurs at lower altitudes, where they inhabit caves and the burrows of ground squirrels and prairie dogs, as well as those of burrowing owls. O. turicata occurs in caves and ground squirrel or prairie dog burrows in the plains regions of the Southwest, feeding off these animals and occasionally burrowing owls or other burrow- or cave-dwelling animals.

In the tick, Borrelia can be found in all the tissues including salivary glands and ovaries of certain subspecies of ticks (Schwan and Piesman 2002). Infected Ornithodoros ticks can transmit relapsing fever spirochetes to humans through their saliva while feeding. O. turicatae and O. parkeri ticks also can transmit spirochetes through secretion of infectious fluids from their coxal glands, which are excretory organs located at the base of the ticks' legs. O. hermsi also secretes infectious coxal fluid but in such small amounts that it dries very quickly after being secreted and, therefore, poses little or no threat to its hosts. Since the infection is also in the ovaries of certain ticks, such as O. hermsi, they can transmit their infections over many generations from female ticks to their offspring. Soft ticks can live up to 10 years. In certain parts of the Russia the same tick has been found to live almost 20 years.

Louse-borne relapsing fever

Borrelia recurrentis is the only agent of louse-borne disease. Pediculus humanus, is the specific vector. Louse-borne relapsing fever is more severe than the tick-borne variety.

Louse-borne relapsing fever occurs in epidemics amid poor living conditions, famine and war in the developing world;[5] it is currently prevalent in Ethiopia and Sudan.

Mortality rate is 1% with treatment; 30-70% without treatment. Poor prognostic signs include severe jaundice, severe change in mental status, severe bleeding, and prolonged QT interval on ECG.

Borrelia species causing relapsing fever include Borrelia recurrentis, caused by human body louse. No animal reservoir exists. Lice that feed on infected humans acquire the Borrelia organisms that then multiply in the gut of the louse. When an infected louse feeds on an uninfected human, the organism gains access when the victim crushes the louse or scratches the area where the louse is feeding. B. recurrentis infects the person via mucous membranes and then invades the bloodstream.

Tick-borne Relapsing Fever

Other relapsing infections are acquired from other Borrelia species, such as Borrelia hermsii or Borrelia parkeri, which can be spread from rodents, and serve as a reservoir for the infection, via a tick vector. Borelia hermsii and Borrelia recurrentis cause very similar diseases although the disease associated with Borrelia hermsii has more relapses and is responsible for more fatalities, while the disease caused by B. recurrentis has longer febrile and afebrile intervals and a longer incubation period.

Tick-borne relapsing fever is found primarily in Africa, Spain, Saudi Arabia, Asia, and certain areas in the Western U.S. and Canada. Most cases occur in the summer months and are associated in particular with sleeping in rustic cabins in mountainous areas of the Western United States. There are approximately 25 cases of TBRF in the United States each year.

Timing

Incubation period = time from tick bite to illness

- 7 days, range 2 to 18 days

Length of illness = time from symptom onset to resolution of symptoms

- 3 days, range 2 to 7 days

Length of time before reoccurrence = time from resolution of symptoms to reoccurence of symptoms

- 7 days, range 4 to 14 days

Number of relapses = number of episodes of reoccurring/relapsing symptoms

- 3 times, can occur up to 10 times in persons who are not treated.[6]

Crisis

As fever is resolving, there is a classic series of stages that a person will go through, collectively known as a "crisis".

1. Phase one is the chill phase, with the person experiencing high fevers up to 41.5°C (106.7°F). With this high temperature, a person can develop delirium, agitation, and confusion. In addition, other signs of an increased metabolic rate are noted, such as a fast heart rate and breathing rate. This phase lasts between 10 and 30 minutes.

2. Phase two is the flush phase. This is where the body temperature decreases rapidly and the person has drenching sweats. During this phase, the person's blood pressure can drop dramatically. [7]

Symptoms

Most people who are infected get sick around 5-15 days after they are bitten by the tick. The symptoms may include a sudden fever, chills, headaches, and muscle or joint aches, arthralgias, sweats and nausea; a rash may also occur. These symptoms continue for 2-9 days, then disappear. This cycle may continue for several weeks if the person is not treated.[8] Other later symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, dry cough, photophobia, rash, neck pain, eye pain, confusion and dizziness. [9]

Physical Examination

Although there can be multiple findings on physical exam there are no classic findings for TBRF. The most evident finding is a moderately ill appearing person who is mildly to moderately dehydrated. Some people develop mild to moderate hepatosplenomegaly, enlarged liver and spleen. Other potential findings on clinical exam include meningismus (stiff neck and headache with photophobia), pleuritic pain and rub (chest pain), photophobia (fear of light).

Skin

Often there is accompanying yellowing of the skin or jaundice. Skin exam can reveal a nonspecific macular rash and/or scattered petechiae.

Eyes

Often there is conjunctivitis (red eyes) and sclarae icteric (yellowing of the white part of the eyes).[10]

Diagnosis

- The definitive diagnosis of TBRF is based on the observation of Borrelia spirochetes in smears of peripheral blood, bone marrow, or cerebrospinal fluid in a symptomatic person. Although best visualized by dark field microscopy, the organisms can also be detected by Wright-Giemsa or acridine orange-stained preparations.

- The organisms are best detected in blood obtained while a person is febrile. With subsequent febrile episodes, the number of circulating spirochetes decreases, making it harder to detect spirochetes on a peripheral blood smear. Even during the initial episode spirochetes will only be seen 70% of the time.

Blood samples obtained before antibiotic treatment can be cultured using BSK medium or by inoculating immature mice. The spirochete will usually be evident within 24 hours if the blood was drawn during a febrile episode.

Although not valuable for making an immediate diagnosis, serologic testing is available through public health laboratories and some private laboratories. Acute serum should be taken within 7 days of symptom onset and convalescent serum should be taken at least 21 days after symptoms start. Early antibiotic treatment may blunt the antibody response and the antibody levels may wane quickly during the months after exposure. To confirm the diagnosis of TBRF, Borrelia specific antibody titers should be increased between acute and convalescent serum samples and convalescent serum antibody levels should be at least two standard deviations above pooled negative controls. Serologic testing for TBRF is not standardized and results may vary by lab. Patients with TBRF may have false-positive tests for Lyme disease because of the similarity of proteins between the two organisms.

Incidental laboratory findings include normal to increased white blood cell count with a left shift towards immature cells, a mildly increased serum bilirubin level, mild to moderate thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), elevated ESR and slightly prolonged coagulation tests, PT and APTT.

Differential Diagnosis

The following infectious disease should be consider in someone with recurrent episodes of a febrile illness:

Colorado tick fever, Infectious mononucleosis, Ascending (intermittent) cholangitis, Yellow fever, African hemorrhagic fevers, Lymphocytic choriomengitis, Dengue fever, Leptospirosis, Infections with echovirus 9, Malaria, Chronic meningococcemia, Infections with Bartonella species, Brucellosis, Rat bite fever.[11]

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

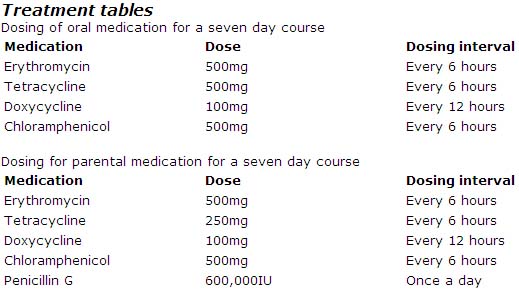

Erythromycin, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, or penicillins have all been shown to be effective for treating TBRF. Although duration of therapy has not been well studied for TBRF, the current recommendation is seven days of antibiotic therapy. In contrast, LBRF caused by B. recurrentis can be treated with a single dose of antibiotics.

For young children and pregnant women either erythromycin and/or penicillin are recommended for treatment of TBRF.

When initiating antibiotic therapy, a patient should be watched closely for a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction for the first 4 hours after the antibiotic is given (Negussie, Remick et al. 1992). The reaction may be difficult to distinguish from a febrile crisis, with rigors and decreased blood pressure. Cooling blankets and appropriate use of antipyrectic agents may be indicated. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction produces apprehension, diaphoresis, fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea with an initial pressor response followed rapidly by hypotension. Recent studies have shown that tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) may be partly responsible for the reaction.

Acute Pharmacotherapies

The CDC has not developed specific treatment guidelines for TBRF. Below are the treatment recommendations as outlined in Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th edition. 2004. p 994.

Prevention

In order to prevent relapsing fever, one should:

- Avoid sleeping in rodent infested buildings.

- Limit tick bites by using insect repellent containing DEET (on skin or clothing) or permethrin (applied to clothing or equipment).

- Rodent-proof buildings in areas where the disease is known to occur.

- Identify and remove any rodent nesting material from walls, ceilings and floors.

- In combination with removing the rodent material, fumigate the building with preparations containing pyrethrins and permethrins. More than one treatment is often needed to effectively rid the building of the vectors, the soft-ticks. Always folllow product product instructions, and consider consulting a liscensed pest control specialist.[13]

See also

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson M.S., M.D.

List of contributors:

Pilar Almonacid

References

- ↑ Schwan T (1996). "Ticks and Borrelia: model systems for investigating pathogen-arthropod interactions". Infect Agents Dis. 5 (3): 167–81. PMID 8805079.

- ↑ Schwan T, Piesman J (2002). "Vector interactions and molecular adaptations of Lyme disease and relapsing fever spirochetes associated with transmission by ticks". Emerg Infect Dis. 8 (2): 115–21. PMID 11897061.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Epidemiology.htm

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Symptoms.htm

- ↑ Cutler S (2006). "Possibilities for relapsing fever reemergence". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (3): 369–74. PMID 16704771.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_biology.htm http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/index.htm http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Symptoms.htm

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_biology.htm http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/index.htm http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Symptoms.htm

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. pp. 432&ndash, 4. ISBN 0838585299.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Symptoms.htm

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Symptoms.htm

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Symptoms.htmhttp://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_LabAnalysis.htm

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Treatment.htm

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/RelapsingFever/RF_Prevention.htm