Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis

|

Premature ventricular contraction Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Premature Ventricular Contraction from other Disorders |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis On the Web |

|

FDA on Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis |

|

CDC onPremature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis |

|

Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis in the news |

|

Blogs on Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis |

|

to Hospitals Treating Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Premature ventricular contraction differential diagnosis |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mugilan Poongkunran M.B.B.S [2] Homa Najafi, M.D.[3] Sahar Memar Montazerin, M.D.[4]

Overview

A premature ventricular contraction originates in the ventricle, and this must be differentiated from an impulse that originates above the ventricle (i.e. it is supraventricular in origin) and conducts with a delay (i.e. a wide complex, it is aberrantly conducted).

Differentiating Premature Ventricular Contraction from other Diseases

Supraventricular Origin of an Impulse with Aberrant Conduction

Aberrant ventricular conduction is:

- A transient form of abnormal intraventricular conduction delay (#IVCD) and occurs when there is unequal refractoriness of the two bundles.

- The right bundle has a longer action potential duration, and is more vulnerable to conduction delay or failure.

- The refractory period is affected by the preceding cycle length.

- The refractory period is longer when there is a long preceding RR interval.

- Aberrant ventricular conduction is favored when a premature supraventricular impulse comes after a long preceding RR interval (Ashman phenomenon).

- If the underlying rhythm is sinus in origin, and if the abnormal QRS is preceded by a premature P wave, then the ectopic beat is likely to be supraventricular in origin.

- The absence of a fully compensatory pause further supports this diagnosis.

- If a retrograde P wave is identifiable after the QRS complex and the RP interval is less than 0.11 second, the premature beat is likely to have originated from the AV junction, since the RP interval is too short for VA conduction (unless an accessory pathway is present).

- A long RP interval of 0.20 seconds or longer is suggestive but not diagnostic of a PVC, since the retrograde conduction time of a junctional beat is less likely to exceed this duration.

- The beat is more likely to be due to aberrancy if the initial forces are similar to those of the sinus beat and if it has an RSR' configuration in lead V1.

- If the QRS complexes in all the precordial leads are positive or all negative, then a PVC is more likely.

- Diagnosis of PVCs in the presence of atrial fibrillation:

- Absence of P waves and the irregularity of the rhythm are the handicaps

- A constant coupling time is suggestive of PVCs

- Ashman phenomenon. Keep in mind that a long cycle length also favors the precipitation of a PVC, therefore this sign is helpful but not diagnostic of aberrancy.

- PVC is favored if the abnormal complex terminates a short-long cycle.

Overview

[Disease name] must be differentiated from other diseases that cause [clinical feature 1], [clinical feature 2], and [clinical feature 3], such as [differential dx1], [differential dx2], and [differential dx3].

OR

[Disease name] must be differentiated from [[differential dx1], [differential dx2], and [differential dx3].

Differentiating [Disease name] from other Diseases

[Disease name] must be differentiated from other diseases that cause [clinical feature 1], [clinical feature 2], and [clinical feature 3], such as [differential dx1], [differential dx2], and [differential dx3].

OR

[Disease name] must be differentiated from [differential dx1], [differential dx2], and [differential dx3].

OR

As [disease name] manifests in a variety of clinical forms, differentiation must be established in accordance with the particular subtype. [Subtype name 1] must be differentiated from other diseases that cause [clinical feature 1], such as [differential dx1] and [differential dx2]. In contrast, [subtype name 2] must be differentiated from other diseases that cause [clinical feature 2], such as [differential dx3] and [differential dx4].

Differentiating [disease name] from other diseases on the basis of [symptom 1], [symptom 2], and [symptom 3]

On the basis [symptom 1], [symptom 2], and [symptom 3], [disease name] must be differentiated from [disease 1], [disease 2], [disease 3], [disease 4], [disease 5], and [disease 6].

| Arrhythmia | Rhythm | Rate | P wave | PR Interval | QRS Complex | Response to Maneuvers | Epidemiology | Co-existing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial Fibrillation (AFib)[1][2] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Atrial Flutter[3] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia (AVNRT)[4][5][6][7] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Multifocal Atrial Tachycardia[8][9] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Premature Atrial Contractrions (PAC)[10][11] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome[12][13] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ventricular Fibrillation (VF)[14][15][16] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ventricular Tachycardia[17][18] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

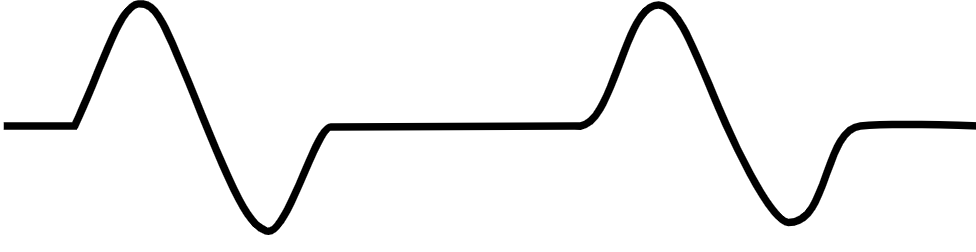

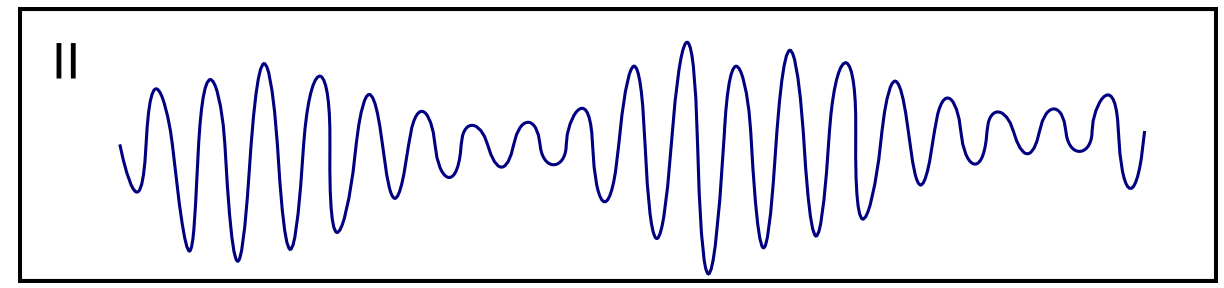

The table below provides information on the differential diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia in terms of ECG appearance:

| Disease Name | Causes | ECG Characteristics | ECG view |

|---|---|---|---|

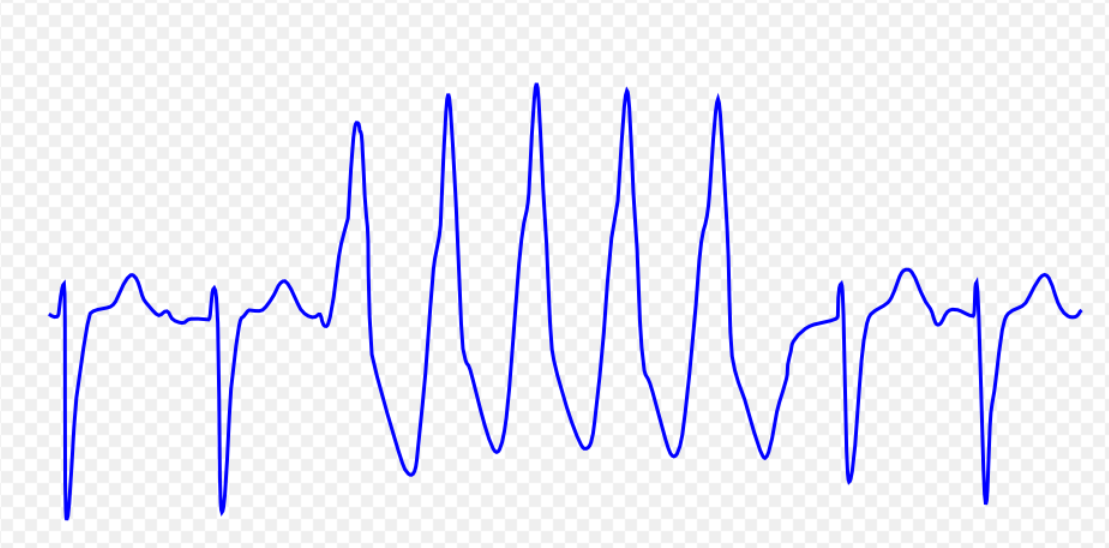

| Ventricular tachycardia [19][20][21][22][23] |

|

| |

| Ventricular fibrillation [17][25][26][27] |

|

| |

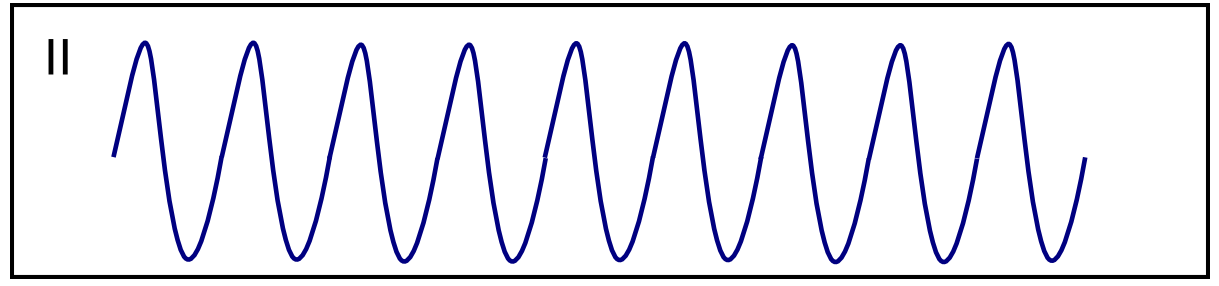

| Ventricular flutter [29][30][31] |

|

| |

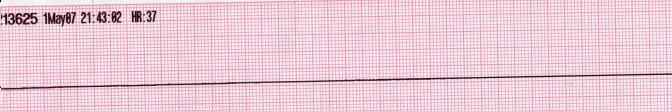

| Asystole [33][34] |

|

| |

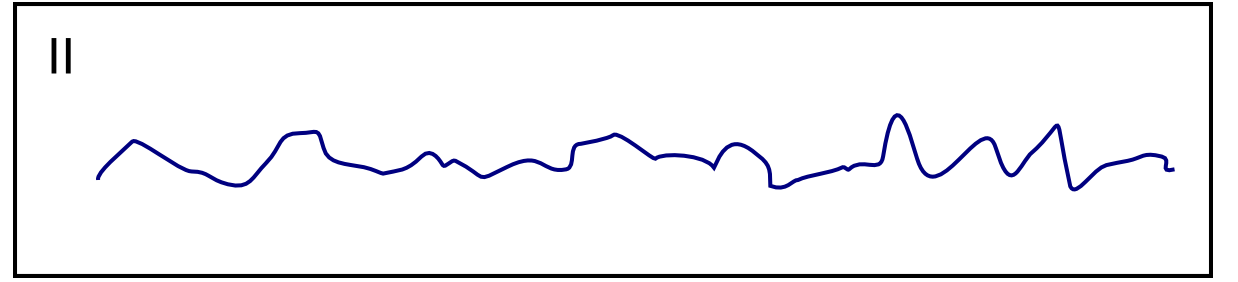

| Pulseless electrical activity [36][37] |

|

|

|

| Torsade de Pointes [39][40][41] |

|

|

References

- ↑ Lankveld TA, Zeemering S, Crijns HJ, Schotten U (July 2014). "The ECG as a tool to determine atrial fibrillation complexity". Heart. 100 (14): 1077–84. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305149. PMID 24837984.

- ↑ Harris K, Edwards D, Mant J (2012). "How can we best detect atrial fibrillation?". J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 42 Suppl 18: 5–22. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2012.S02. PMID 22518390.

- ↑ Cosío FG (June 2017). "Atrial Flutter, Typical and Atypical: A Review". Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 6 (2): 55–62. doi:10.15420/aer.2017.5.2. PMC 5522718. PMID 28835836.

- ↑ Katritsis DG, Josephson ME (August 2016). "Classification, Electrophysiological Features and Therapy of Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia". Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 5 (2): 130–5. doi:10.15420/AER.2016.18.2. PMC 5013176. PMID 27617092.

- ↑ Letsas KP, Weber R, Siklody CH, Mihas CC, Stockinger J, Blum T, Kalusche D, Arentz T (April 2010). "Electrocardiographic differentiation of common type atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia from atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia via a concealed accessory pathway". Acta Cardiol. 65 (2): 171–6. doi:10.2143/AC.65.2.2047050. PMID 20458824.

- ↑ "Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia (AVNRT) - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf".

- ↑ Schernthaner C, Danmayr F, Strohmer B (2014). "Coexistence of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia with other forms of arrhythmias". Med Princ Pract. 23 (6): 543–50. doi:10.1159/000365418. PMC 5586929. PMID 25196716.

- ↑ Scher DL, Arsura EL (September 1989). "Multifocal atrial tachycardia: mechanisms, clinical correlates, and treatment". Am. Heart J. 118 (3): 574–80. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(89)90275-5. PMID 2570520.

- ↑ Goodacre S, Irons R (March 2002). "ABC of clinical electrocardiography: Atrial arrhythmias". BMJ. 324 (7337): 594–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7337.594. PMC 1122515. PMID 11884328.

- ↑ Lin CY, Lin YJ, Chen YY, Chang SL, Lo LW, Chao TF, Chung FP, Hu YF, Chong E, Cheng HM, Tuan TC, Liao JN, Chiou CW, Huang JL, Chen SA (August 2015). "Prognostic Significance of Premature Atrial Complexes Burden in Prediction of Long-Term Outcome". J Am Heart Assoc. 4 (9): e002192. doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.002192. PMC 4599506. PMID 26316525.

- ↑ Strasburger JF, Cheulkar B, Wichman HJ (December 2007). "Perinatal arrhythmias: diagnosis and management". Clin Perinatol. 34 (4): 627–52, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2007.10.002. PMC 3310372. PMID 18063110.

- ↑ Rao AL, Salerno JC, Asif IM, Drezner JA (July 2014). "Evaluation and management of wolff-Parkinson-white in athletes". Sports Health. 6 (4): 326–32. doi:10.1177/1941738113509059. PMC 4065555. PMID 24982705.

- ↑ Rosner MH, Brady WJ, Kefer MP, Martin ML (November 1999). "Electrocardiography in the patient with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: diagnostic and initial therapeutic issues". Am J Emerg Med. 17 (7): 705–14. doi:10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90167-5. PMID 10597097.

- ↑ Glinge C, Sattler S, Jabbari R, Tfelt-Hansen J (September 2016). "Epidemiology and genetics of ventricular fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction". J Geriatr Cardiol. 13 (9): 789–797. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.09.006. PMC 5122505. PMID 27899944.

- ↑ Samie FH, Jalife J (May 2001). "Mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia and its transition to ventricular fibrillation in the structurally normal heart". Cardiovasc. Res. 50 (2): 242–50. doi:10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00289-3. PMID 11334828.

- ↑ Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, Gersh BJ (April 2010). "Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors". Nat Rev Cardiol. 7 (4): 216–25. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2010.3. PMC 5014372. PMID 20142817.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Koplan BA, Stevenson WG (March 2009). "Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death". Mayo Clin. Proc. 84 (3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61149-X. PMC 2664600. PMID 19252119.

- ↑ Levis JT (2011). "ECG Diagnosis: Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia". Perm J. 15 (1): 65. doi:10.7812/tpp/10-130. PMC 3048638. PMID 21505622.

- ↑ Ajijola, Olujimi A.; Tung, Roderick; Shivkumar, Kalyanam (2014). "Ventricular tachycardia in ischemic heart disease substrates". Indian Heart Journal. 66: S24–S34. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2013.12.039. ISSN 0019-4832.

- ↑ Meja Lopez, Eliany; Malhotra, Rohit (2019). "Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease". Journal of Innovations in Cardiac Rhythm Management. 10 (8): 3762–3773. doi:10.19102/icrm.2019.100801. ISSN 2156-3977.

- ↑ Coughtrie, Abigail L; Behr, Elijah R; Layton, Deborah; Marshall, Vanessa; Camm, A John; Shakir, Saad A W (2017). "Drugs and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia risk: results from the DARE study cohort". BMJ Open. 7 (10): e016627. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016627. ISSN 2044-6055.

- ↑ El-Sherif, Nabil (2001). "Mechanism of Ventricular Arrhythmias in the Long QT Syndrome: On Hermeneutics". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 12 (8): 973–976. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00973.x. ISSN 1045-3873.

- ↑ de Riva, Marta; Watanabe, Masaya; Zeppenfeld, Katja (2015). "Twelve-Lead ECG of Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease". Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 8 (4): 951–962. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002847. ISSN 1941-3149.

- ↑ ECG found in of https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Maury P, Sacher F, Rollin A, Mondoly P, Duparc A, Zeppenfeld K, Hascoet S (May 2017). "Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in tetralogy of Fallot". Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 110 (5): 354–362. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2016.12.006. PMID 28222965.

- ↑ Saumarez RC, Camm AJ, Panagos A, Gill JS, Stewart JT, de Belder MA, Simpson IA, McKenna WJ (August 1992). "Ventricular fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is associated with increased fractionation of paced right ventricular electrograms". Circulation. 86 (2): 467–74. doi:10.1161/01.cir.86.2.467. PMID 1638716.

- ↑ Bektas, Firat; Soyuncu, Secgin (2012). "Hypokalemia-induced Ventricular Fibrillation". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 42 (2): 184–185. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.079. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Thies, Karl-Christian; Boos, Karin; Müller-Deile, Kai; Ohrdorf, Wolfgang; Beushausen, Thomas; Townsend, Peter (2000). "Ventricular flutter in a neonate—severe electrolyte imbalance caused by urinary tract infection in the presence of urinary tract malformation". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00161-4. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ Koster, Rudolph W.; Wellens, Hein J.J. (1976). "Quinidine-induced ventricular flutter and fibrillation without digitalis therapy". The American Journal of Cardiology. 38 (4): 519–523. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(76)90471-9. ISSN 0002-9149.

- ↑ Dhurandhar RW, Nademanee K, Goldman AM (1978). "Ventricular tachycardia-flutter associated with disopyramide therapy: a report of three cases". Heart Lung. 7 (5): 783–7. PMID 250503.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ ACLS: Principles and Practice. p. 71-87. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003. ISBN 0-87493-341-2.

- ↑ ACLS for Experienced Providers. p. 3-5. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003. ISBN 0-87493-424-9.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care - Part 7.2: Management of Cardiac Arrest." Circulation 2005; 112: IV-58 - IV-66.

- ↑ Foster B, Twelve Lead Electrocardiography, 2nd edition, 2007

- ↑ ECG found in wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Li M, Ramos LG (July 2017). "Drug-Induced QT Prolongation And Torsades de Pointes". P T. 42 (7): 473–477. PMC 5481298. PMID 28674475.

- ↑ Sharain, Korosh; May, Adam M.; Gersh, Bernard J. (2015). "Chronic Alcoholism and the Danger of Profound Hypomagnesemia". The American Journal of Medicine. 128 (12): e17–e18. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.051. ISSN 0002-9343.

- ↑ Khan IA (2001). "Twelve-lead electrocardiogram of torsades de pointes". Tex Heart Inst J. 28 (1): 69. PMC 101137. PMID 11330748.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page