Pericarditis

| Pericarditis | ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

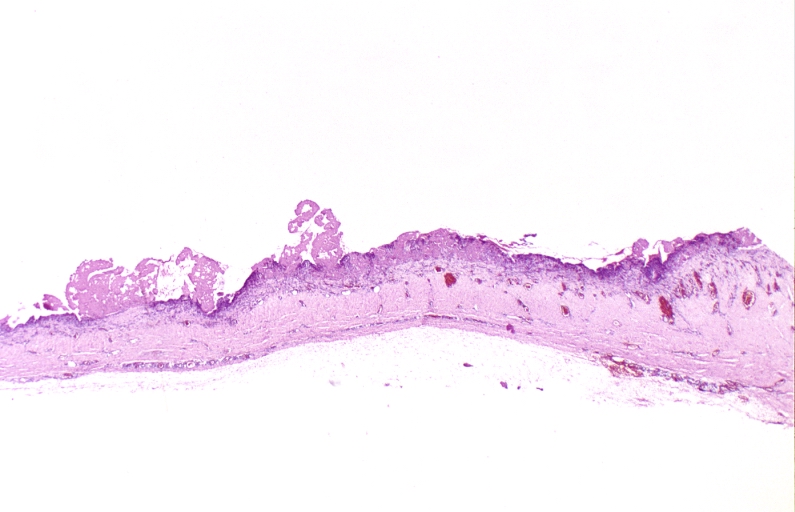

| Mesothelial cyst of the pericardium. Note the rounded mass in the right costophrenic angle (arrow). Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | ||

| ICD-10 | I01.0, I09.2, I30-I32 | |

| ICD-9 | 420.90 | |

| DiseasesDB | 9820 | |

| MedlinePlus | 000182 | |

| eMedicine | med/1781 emerg/412 | |

| MeSH | C14.280.720 | |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Pericarditis |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Pericarditis Most cited articles on Pericarditis |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Pericarditis |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Pericarditis at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Pericarditis at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Pericarditis

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Pericarditis Discussion groups on Pericarditis Patient Handouts on Pericarditis Directions to Hospitals Treating Pericarditis Risk calculators and risk factors for Pericarditis

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Pericarditis |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Pericarditis further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Pericarditis is an inflammation of the pericardium (the fibrous sac surrounding the heart). Pericarditis is further classified according to the composition of the inflammatory exudate: serous, purulent, fibrinous, and hemorrhagic types occur.

Acute pericarditis is more common than chronic pericarditis, and can occur as a complication of infections, immunologic conditions, or heart attack.

Pathophysiology & Etiology

Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardium, the double-walled sac that contains the heart and the roots of the great vessels. There can be an accompanying accumulation of fluid that can be either serous (free flowing fluid) or fibrinous (an exudate, which is a thick fluid composed of proteins, fibrin strands, inflammatory cells, cell breakdown products, and sometimes bacteria). Vascular congestion of the pericardium is also present. The underlying myocardium may or may not be inflammed as well. If the myocardium is involved in the inflammatory process, then this is called myopericarditis, and the CK and troponin may be elevated.

The signs and symptoms of acute pericarditis can be misleading because they can occur as part of a constellation of symptoms associated with another illness.

The Most Frequent Causes of Pericarditis [1]

- (35%) Neoplastic

- (23%) Autoimmune

- (21%) Viral - adenovirus, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, influenza virus, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex virus, etc

- ( 6%) Bacterial (other than tuberculosis)

- ( 6%) Uremia

- ( 4%) Tuberculosis

- ( 4%) Idiopathic

- (remaining) trauma, drugs, post-AMI, myocarditis, dissecting aortic aneurysm, radiation

Complete List of Causes of pericarditis

- Infectious:

- Viral: Coxsackie B Virus, Echovirus, Adenovirus (less commonly: Mumps, Influenza, varicella, Hepatitis B and CMV-especially in HIV patients.) Usually associated with a viral prodrome and acute pericarditis.

- Tuberculosis: usually bloody, protein greater than 2.5. Initially mostly polymorphonuclear cells, later lymphocytes, monocytes and plasma cells. Usually develops very slowly with significant fibrous reaction. Initially effusive then becomes constrictive.

- Purulent: Pneumococcus, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus most common. Also Proteus, E.coli, Psuedomonas, Klebsiella, Brucellosis, Salmonella, Neisseria, Haemophilus influenza, Tularemia, Legionella, preodominantly by hematogenous spread and approximately 20% by contiguous spread. Usually these patients are quite ill.

- Fungal: Histoplasmosis, Coccidiomycosis, Aspergillus, Blastomycosis, Candida.

- Other: Toxoplasmosis, Amebiasis, Mycoplasma, Nocardia, Actinomycosis, Echinococcus, Lyme disease (usually myopericarditis associated with conduction abnormalities).

- Neoplastic:

- Predominantly lung, breast, leukemia, lymphomas (Hodgkins and non-Hodgkins). Less commonly GI malignancies, ovarian cancer, sarcomas and melanomas, metastic, hematogenous, carcinoma, carcinoid, Sipple syndrome, mesothelioma, fibroma, lipoma . Also Kaposis sarcoma in HIV positive patients.

- Uremic:

- Uremic pericarditis is seen in up to 20% of uremic patients requiring chronic hemodialysis. The mechanism is unknown. Most commonly there is a small effusion associated with pain and a pericardial friction rub, but there can be a large effusion and present with tamponade.

- Autoimmune:

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus or SLE: Pericarditis usually occurs in the setting of disease flares (systemic symptoms, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) , +ANA, +dsDNA, pleural effusions). Occurs in 20-40% of patients with SLE during the course of the disease. Usually the fluid is serous or grossly bloody. Analysis of the fluid usually reveals a high protein and low glucose content. Typically WBC count is less than 10K, and is made up of primarily polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs).

- Rheumatoid arthritis or RA: Pericarditis can occur without active joint involvement. Also serous or bloody. Usually the protein is > 5 mg/dl, and the glucose is low (<45). The WBC is high at 20-90K. Complement is usually low, and the latex fixation test is usually positive.

- Other: Acute rheumatic fever, scleroderma, mixed connective tissue disease, Wegener's, PAN.

- Traumatic:

- After chest trauma, throacic surgery, PCM insertion, Valvuloplasty. Also from esophageal rupture, pancreatic-pericardial fistula (check amylase), penetrating chest injury, esophogeal perforation, gastric perforation, during catheterization (pacemaker insertion, cathether ablation for arrhythmias, diagnostic, PCI with coronary dissection).

- Drugs:

- Usually associated with small effusions. Common culprits include hydralazine, procainamide, DOH, isoniazid, phenylbutazone, dantrolene, doxorubicin, methylsergide, penicillin.

- Hypothyroidism:

- Usually in conjunction with clinically severe hypothyroidism. Most early case reports associated with myxedema and patients also had ascites, pleural effusions and uveal edema. Often resolves with thyroid replacement therapy.

- Other:

- Post-MI (Dresslers), post-pericardiotomy, radiation, dissecting aortic aneurysm, chylopericardium (from thoracic duct obstruction secondary to tumor, surgical procedure, trauma, TB, congenital). Also, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, IBD, Whipple's, temporal arteritis and Behcet syndrome).

Clinical presentation

Chest pain, radiating to the back and relieved by sitting up forward and worsened by lying down, is the classical presentation. Other symptoms of pericarditis may include dry cough, fever, fatigue and anxiety. Pericarditis can be misdiagnosed as myocardial infarction, and vice versa.

The classic sign of pericarditis is a friction rub. Other signs include ST-elevation and PR-depression on EKG (all leads); cardiac tamponade (pulsus paradoxus with hypotension), and congestive heart failure (elevated jugular venous pressure with peripheral edema).

Natural History

Most cases of acute idiopathic pericarditis resolve without complications or recurrence. Complications may include:

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

A diagnosis of pericarditis can be made depending on its etiology and speed of onset. For example, both uremic and tuberculosis induced pericarditis develop more slowly and can be undetectable until presenting "as a fever of unknown origin." On the other hand, both bacterial and viral pericarditis develop rapidly and can present as increasing "pain over several hours."

Symptoms:

- Chest Pain: however, pain is often absent (depending on the type of pericarditis e.g. rheumatoid pericarditis). It is the most common symptom.

- Some causes of pain include: inflammation of the pericardium, phrenic nerves, and nearby pleura.

- Quality of pain: sharp, "sticking", dull, aching, or pressure-like. It can be rated anywhere from 1-10. In the beginning stages, the pain usually starts out as sharp. "Inspiration and cough" can increase the pain so patients usually "sit upright for relief."

- Nonproductive cough that elicites pleuritic pain

- Productive cough, which usually occurs in the presence of other illness(es)

- Hiccup (rarely)

- Odynophagia with or without Dysphagia

- Faintness and Dizziness (uncommon unless cardiac tamponade is present]]

- Chest wall palpitations: causing local tenderness and may be indicative of costochondritis, Tietze syndrome, or rib fractures (in cases of traumatic pericarditis)

Physical Examination

Appearance of the Patient with Pericarditis

- Fever less than 39° C or 102.2° F

- Patients who are elderly may not exhibit fever; however, they may be hypothermic especially those with renal failure.

- Chills (suppurative pericarditis and idiopathic (viral) pericarditis)

- Weakness

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Pallor (may also indicate tuberculosis, uremia, neoplasia, and rheumatic carditis)

Heart

Ausculatory Phenomena:

- Pericardial Rub(s): Usually heard with acute pericarditis, sometimes with subacute and chronic. This is the major indicator of pericarditis.

- endopericardial rub: inflamed, scarred or tumor-invaded serosal surfaces

- exopericardial rub: after sclerotherapy of effusions, between parietal pericardium and pleura or chest wall (occasionally)

- endo-exopericardial rub: both of the above

- pleuropericardial rub: pleuritis as a result of pleural or both pleural and pericardial both

- Abnormal Heart Sounds:

- Sounds are dampened as a result of fluid insullation

- Hemodynamic changes diminish S1 and S2

- Clicks: Ventricular volume shrinks disproportionately and psuedoprolapse/true prolapse of mitral and/or tricuspid valvular structures result in clicks.

- Murmurs: are epiphenomena and may be present if there is coinciding heart disease, narrowing of a valve, aorta, pulmonary artery or another area of the heart.

Lungs

Rales are frequent examination findings, occasionally pleural fluid may present.

Extremities

- May be poorly perfused in the setting of tamponade

- Edema may be present in the setting of pericardial constriction

Laboratory Findings

Electrolyte and Biomarker Studies

Inflammatory markers. A CBC may show an elevated white count and a serum C-reactive protein may be elevated.

Molecular markers. Acute pericarditis is associated with a modest increase in serum creatine kinase MB (CK-MB)[2][3] and cardiac troponin I (cTnI)[4][5], both of which are also markers for myocardial injury. Therefore, it is imperative to also rule out acute myocardial infarction in the face of these biomarkers. The elevation of these substances is related to inflammation of the myocardium. Also, ST elevation on EKG (see below) is more common in those patients with a cTnI > 1.5 µg/L[5]. Coronary angiography in those patients should indicated normal vascular perfusion. The elevation of these biomarkers are typically transient and should return to normal within a week. Persistence may indicated myopericarditis. As a summary:

- ESR: mild to marked elevation

- CRP: mild to marked elevation

- CK-MB: depends on the extent of myocardial involvement

- LDH: depends on the extent of myocardial involvement

- troponin I: depends on the extent of myocardial involvement

- serum myoglobin: normal (but not always, usually rises with increased ST segment deviation

- gallium-67 scanning: helps ID "inflammatory and leukemic infiltrations"

Electrocardiogram

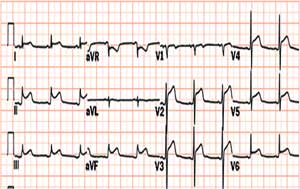

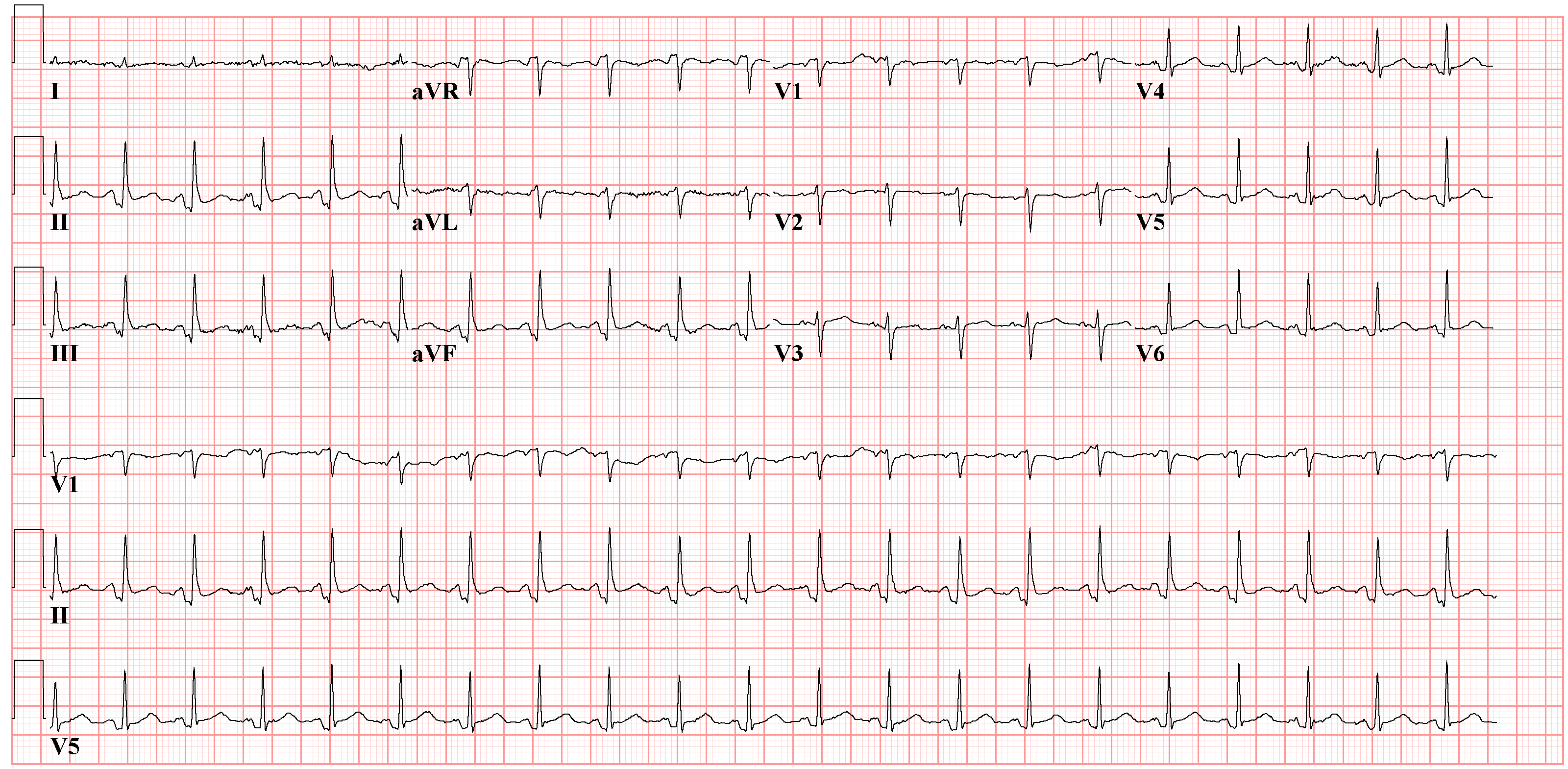

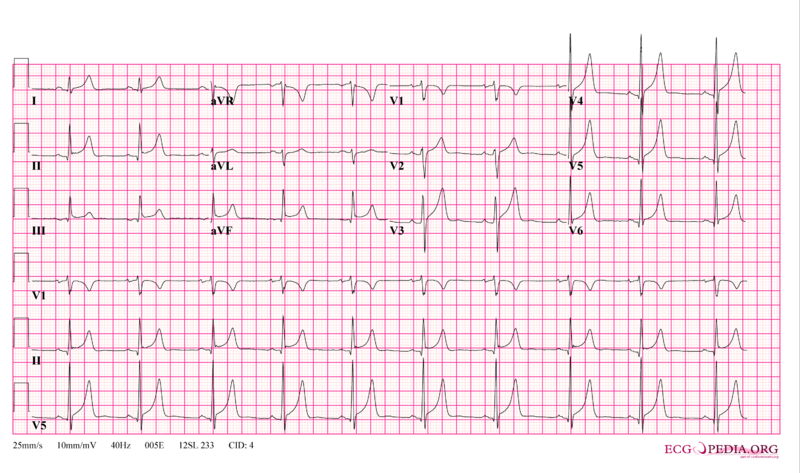

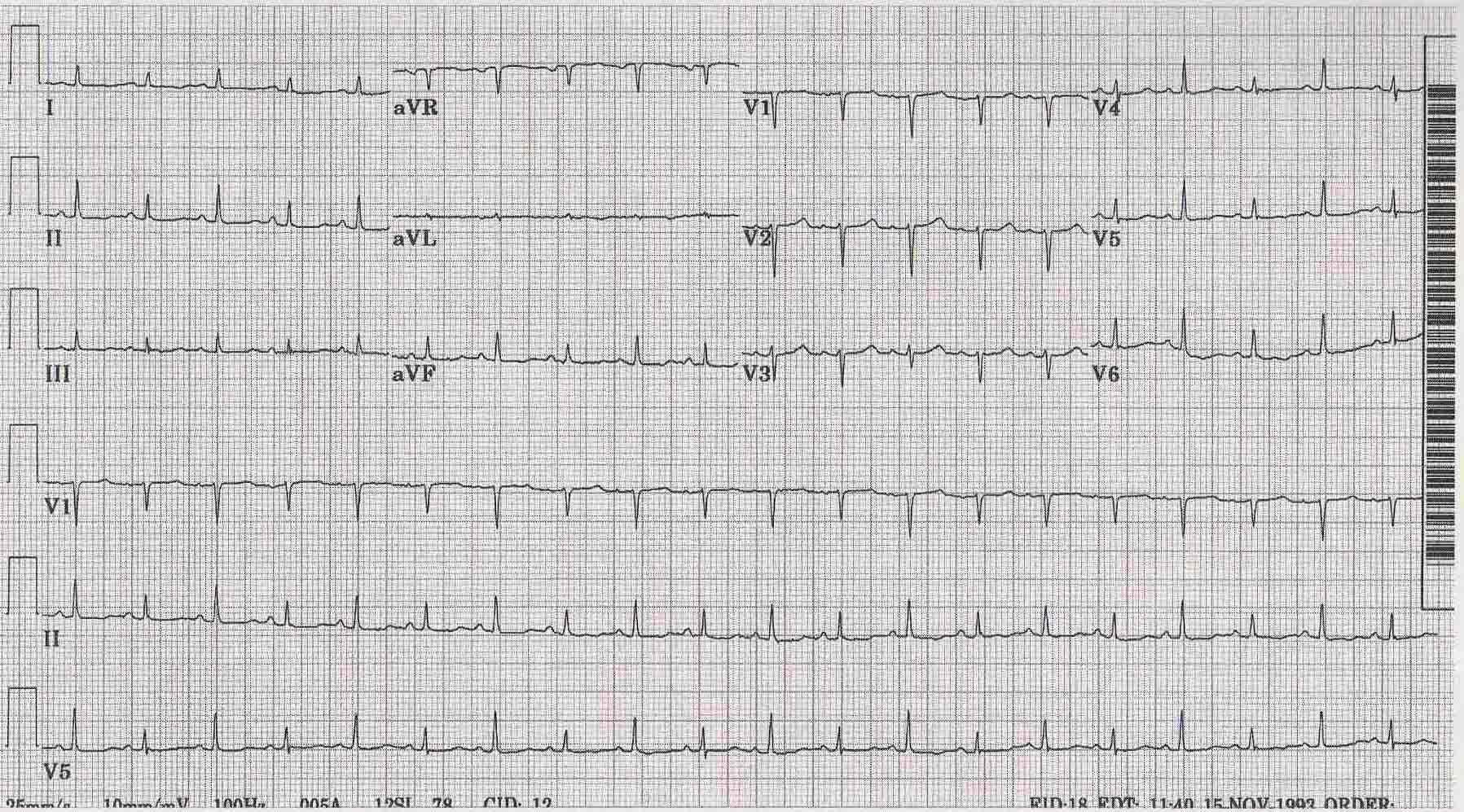

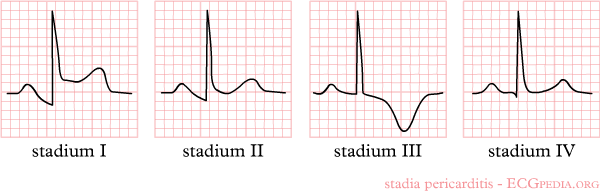

ECG Abnormalities: Increase in scar tissue, fluid and fibrin can reduce voltage, quasi-specific ST-T waves can present. The ECG abnormalities vary depending on the stage/severity of the pericarditis. Below are the stages/types of pericarditis:[6][2]

- Acute Pericarditis (see also Electrocardiography#The PR Interval and Electrocardiography#The EKG of Cardiac Transplantation): this variation of the disease in conjunction with myocarditis can lead to ST-T anomalies that are characteristic of the acute stages of pericarditis.

- Stage 1: Stage 1 of acute pericarditis, in and of itself, presents as "early repolarization" and acute infarction. It shows signs of anterior and inferior ST elevation on the ECG. There are usually no deviations in the QRS complex. This stage is largely characteristic of acute pericarditis when almost all of the leads are effected. Leads I, II, avL, avF, and V3-V6.

- Stage 2: During the early phase of this stage, ST segments should become baseline again; whereas, PR segments may have deviated. During the latter phase of stage 2, the ST segments that were previously elvated usually flatten and invert.

- Stage 3: Virtually all of the leads in stage 3 exhibit T wave inversion. Acute pericarditis cannot be diagnosed on an ECG of a stage 3 patient because its presentation is the same as myocardial injury and frank myocarditis.

- Stage 4: This stage presents itself on the ECG as a return to a prepericarditis state. Stage 4 does not always occur and in its absence, there can be residual T wave inversions that may be permanent, generalized or focal.

- Rate and Rhythm: Rapid heart rates are typical in patients with pericarditis, but in patients with uremic pericarditis slower rates are observed. Heart rhythms appear normal unless there is another complication such as cardiac disease, the presence of myocardial/pericardial tumor, or a metabolic disorder.

- Pericardial Effusion (see also Electrocardiography#Amplitude): These can present differently on the ECG depending on whether they are chronic vs large effusions. The former typically leads to low amplitude ECGs; whereas, the latter can show no voltage or various ECG abnormalities. ST-T wave abnormalities can be caused by superficial myocarditis or because of the accumulated fluid, they may be caused by the compression of the myocardium or ischemia. The primary cause of ST segment variation during pericardial effusions is usually the rapid accumulation of fluid. Large effusions can lead to the reduction of P wave voltage. Pleural effusions can cause a decrease in voltage, which occurs mainly on the left. Also, cirrhosis and congestive heart failure (CHF), which similarily involve the accumulation of fluid in the body, can decrease voltage in the absence of any pericardial disease.

- Cardiac tamponade (see also Cardiac tamponade#Electrocardiogram): Generally has little ECG effect; however, in the acute form, tamponade may present on the ECG as any one of the stages of acute pericarditis.

- Electrical Alternation: This occurs more often in cases of tamponade than in those of pericarditis (2:1). There is alternation of the QRS complex on the spatial axis. Alternation of the T wave, P wave, and PR segement are difficult to see and are uncommon. The removal of even a small amount of fluid can end alternation.

- Early Repolarization: This finding can be misleading and may look like pericarditis, when in fact it is not. A strong indication of pericarditis is "if the J point is more than 25% the height of the T wave apex."

- Constrictive Pericarditis: Cases of constrictive pericarditis have nonspecific ECG abnormalities. Common abnormalities include: a slightly "low voltage QRS" segment combined with "flattened to inverted T waves", during stage 3 of acute/subacute constriction the T wave inversions remain or worsen and "P waves can be wide and bifid." It is not uncommon for patients to have normal ECGs. Many patients may only exhibit "nonspecific T wave abnormality." Other influencial factors that may effect the ECG in constrictive pericarditis are: fluid retention, ascites, and pleural effusions. The two most common arrhythmias that occur are atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter.

- QRS Abnormality: characteristic RV hypertrophy QRS abnormalities may develop as a result of disproportionate constriction or postpericardiectomy scarring. Also, "focal atrophy, scarring or inflamation" may cause "abnormal Q waves."

- Chronic Constrictive Pericarditis: low volatage and myocardial atrophy, "frontal QRS axis" is usually vertical (becomes more vertical with increasing chronicity),

- Acute/Subacute Pericarditis: QRS axis appears as normal

- QRS Abnormality: characteristic RV hypertrophy QRS abnormalities may develop as a result of disproportionate constriction or postpericardiectomy scarring. Also, "focal atrophy, scarring or inflamation" may cause "abnormal Q waves."

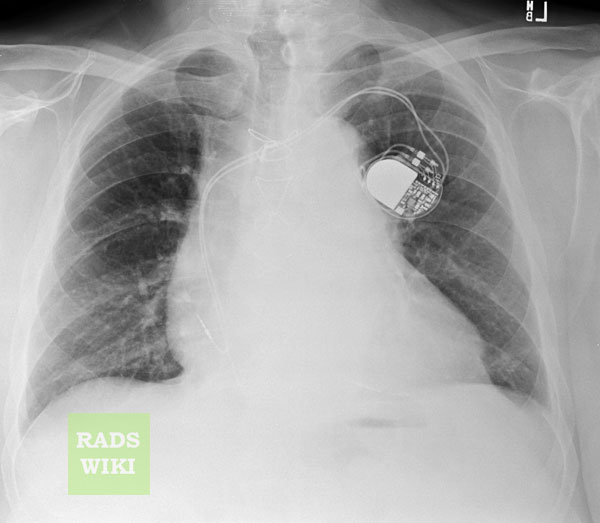

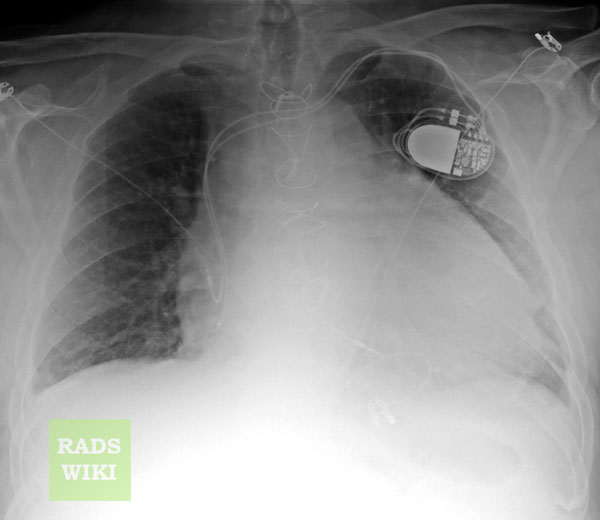

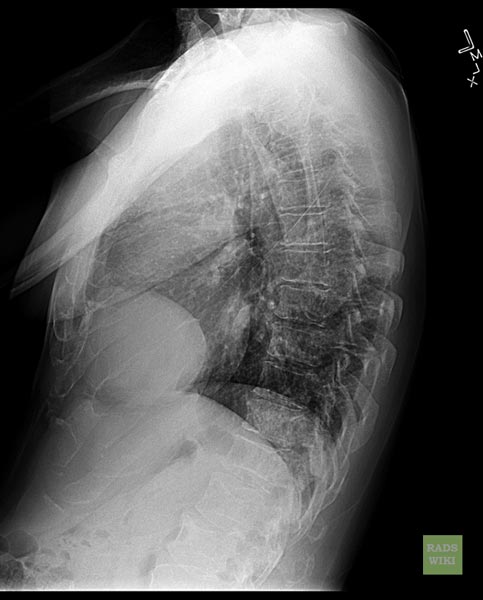

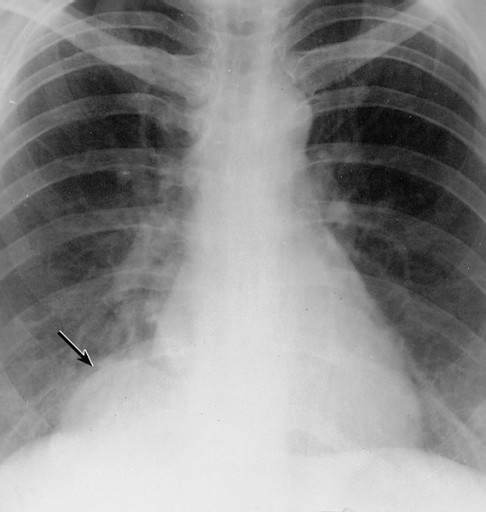

Chest X Ray

The heart will be enlarged on CXR in the setting of tamponade with a significant pericardial effusion.

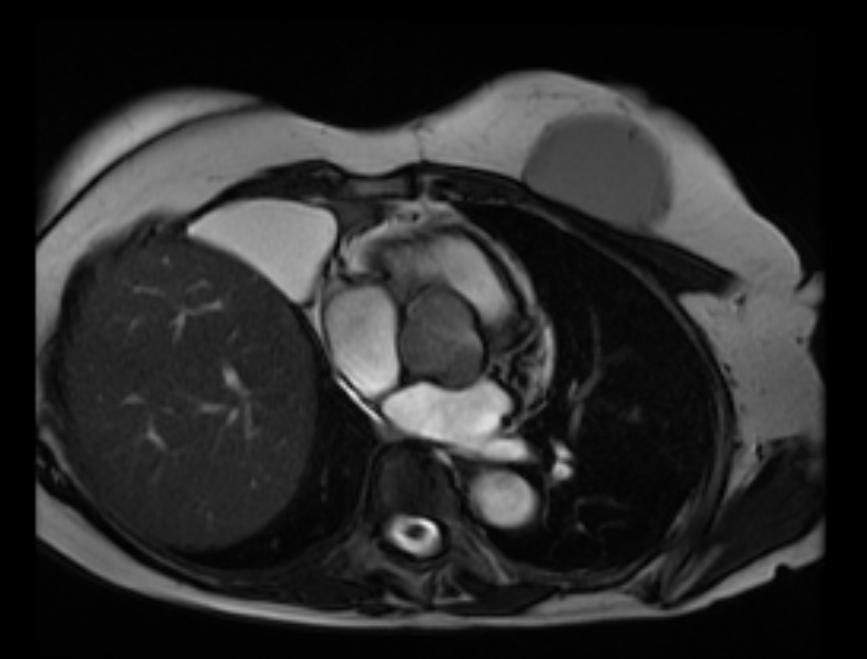

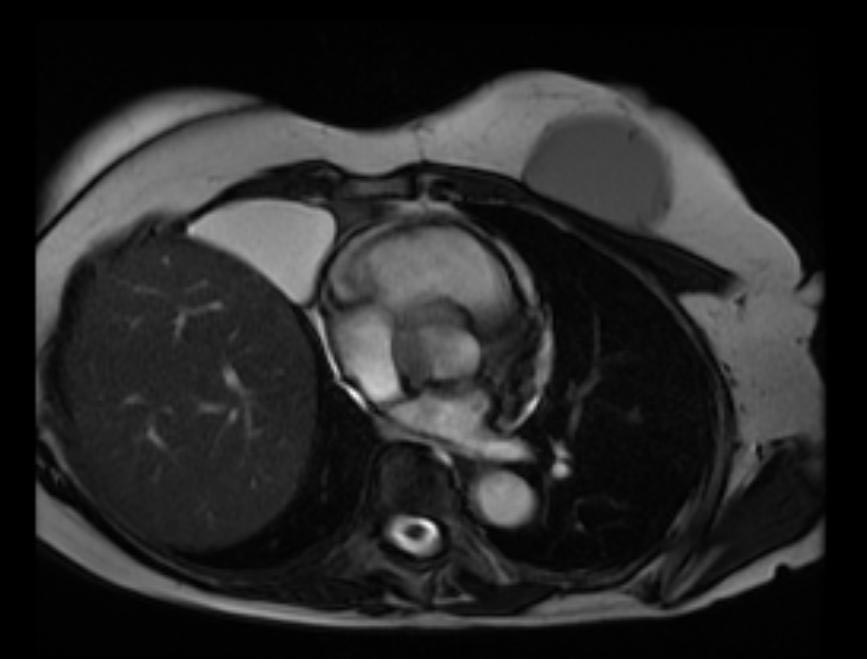

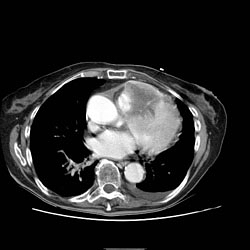

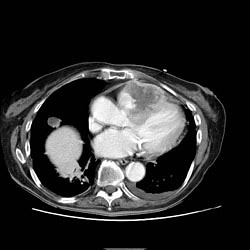

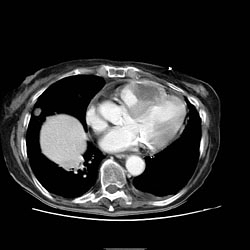

MRI and CT [7] [8] [9]

Pericardial Effusion

Cross-sectional imaging by CT or MRI is very sensitive in the detection of generalized or loculated pericardial effusions. Some fluid in the pericardial sac contributes to the apparent thickness and should be considered normal. Commonly, free-flowing fluid accumulates first at the posterolateral aspect of the left ventricle, when the patient is imaged in the supine position.

Estimation of the amount of fluid is possible to a limited extent based on the overall thickness of the crescent of fluid. Compared to cardiac ultrasound, CT and MRI may be particularly helpful in detecting loculated effusions, owing to the wide field of view provided by these techniques. Hemorrhagic effusions can be differentiated from a transudate or an exudate based on signal characteristics (high signal on T1-weighted images) or density (high-density clot on CT). Pulsation artefacts may cause local areas of low signal in a hemorrhagic effusion. Effusions are often incidentally noted on CT scans obtained for other indications.

Pericardial thickening (thickness >4 mm) is difficult to differentiate from a small generalized effusion. Both entities will reveal a low signal/density line that is thicker than the normal pericardial thickness. In acute pericarditis, the pericardial lining can show intermediate signal intensity and may enhance after gadolinium administration.

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted

-

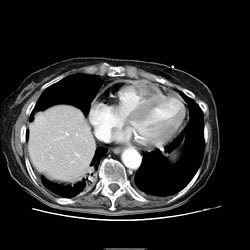

Chest x-ray: Pericardial effusion

-

Chest x-ray: Pericardial effusion. The second day of admission

-

Cardiac MSCT: Pericardial effusion

Constrictive Pericarditis

Pericardial thickening may result in constrictive pericarditis. In this entity, pericardial thickening will hamper cardiac function, with hemodynamic consequences. Many disease conditions can lead to constrictive pericarditis (infection, tumor, radiation, heart surgery, etc.).

The diagnostic features include thickened pericardium in conjunction with signs of impaired right ventricular function: dilatation of caval veins and hepatic veins, enlargement of the right atrium, and the right ventricle itself may be normal or even reduced (tubular, sigmoid) in size due to compression. Localized pericardial thickening may also cause functional impairment (localized constrictive pericarditis). Sometimes constriction may occur despite a normal appearance of the pericardium.

Pericardial calcifications are easily visualized by CT but may be difficult or impossible to appreciate on MRI.

Pericardial Tumor

A pericardial cyst is most commonly located at the right cardiophrenic angle. On T1, it appears either as a low signal or an intermediate signal due to high protein content, or with a characteristic light-bulb appearance on T2.

Unusual tumors may arise from the pericardium (mesothelioma, angiosarcoma, etc.). Malignant primary tumors have many overlapping imaging features and generally cannot be differentiated. The role of cross-sectional imaging is to establish a diagnosis and to define the extent of the lesion (invasion of cardiac structures, veins, pericardium, etc.). Sometimes lesions may have helpful signal characteristics to suggest a specific diagnosis, e.g., high-signal fat on T1 or low-density fat on CT in lipoma / liposarcoma.

Secondary tumors are much more common than primary tumors. Lung cancer may invade the mediastinal and cardiac structures directly or indirectly.

The most common secondary tumors affecting the heart are lung cancer, breast cancer, and lymphoma. Metastatic pericardial disease commonly presents as hemorrhagic effusion. Tumor nodules may enhance after intravenous gadolinium administration.

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted

Pericardial Metastases

Echocardiographic Findings

Radioscopic Findings

- Calcified pericardium in constructive pericarditis

<youtube v=blSXL5z02fY/>

<youtube v=LXWitpJQEGQ/>

Pathological Findings

Gross Images

-

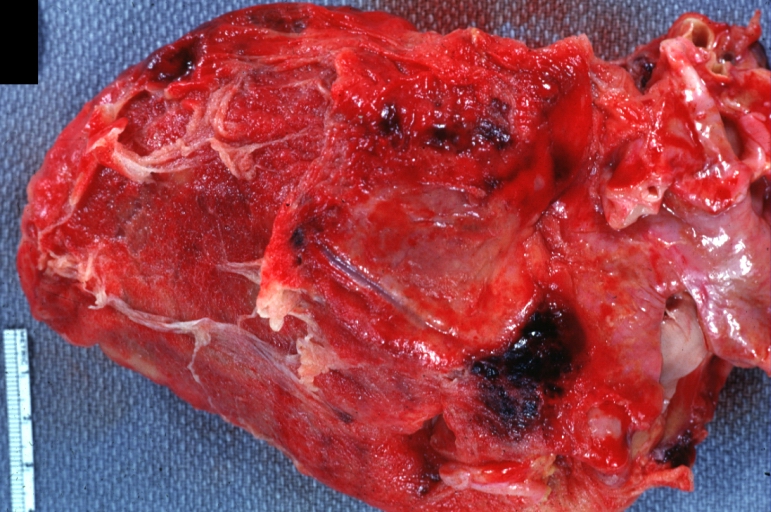

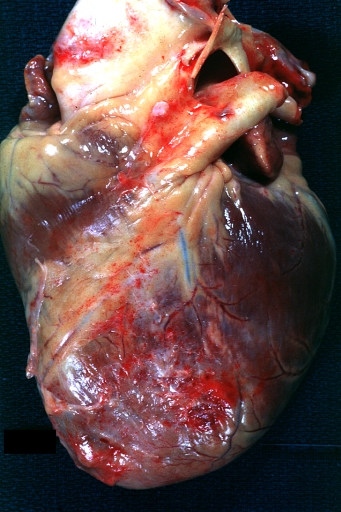

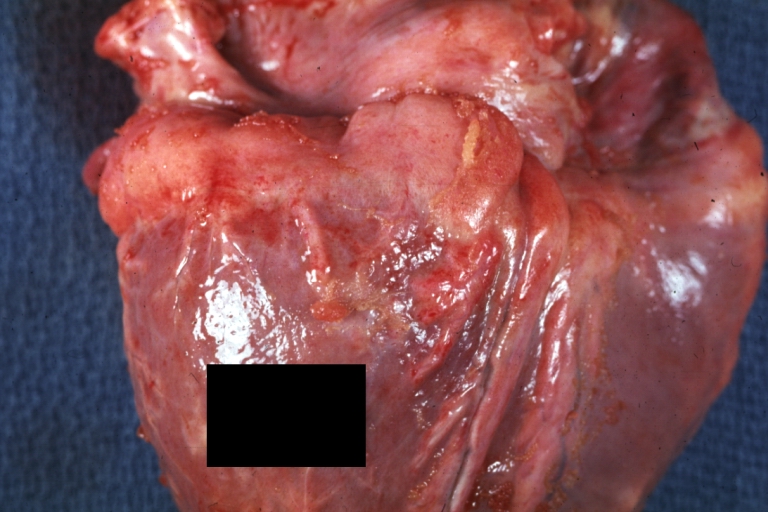

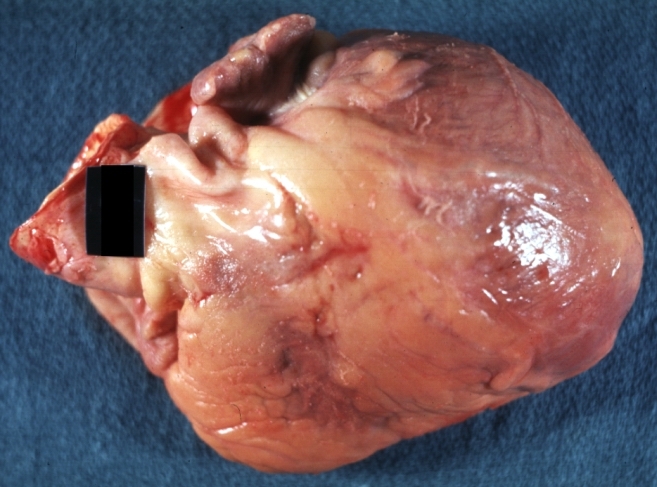

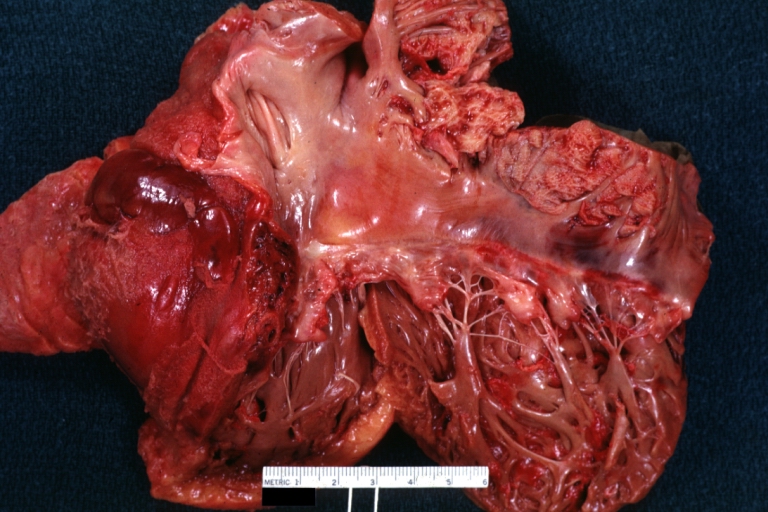

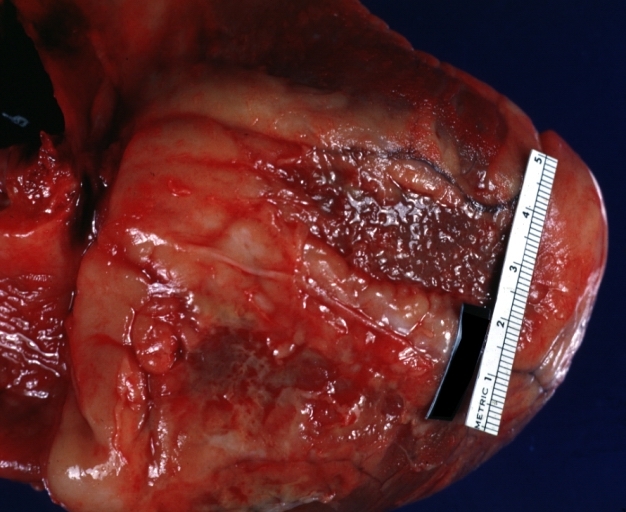

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, an excellent example of bread and butter appearance. Uremia, chronic glomerulonephritis and sepsis.

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a good example (bread and butter appearance).

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example.

-

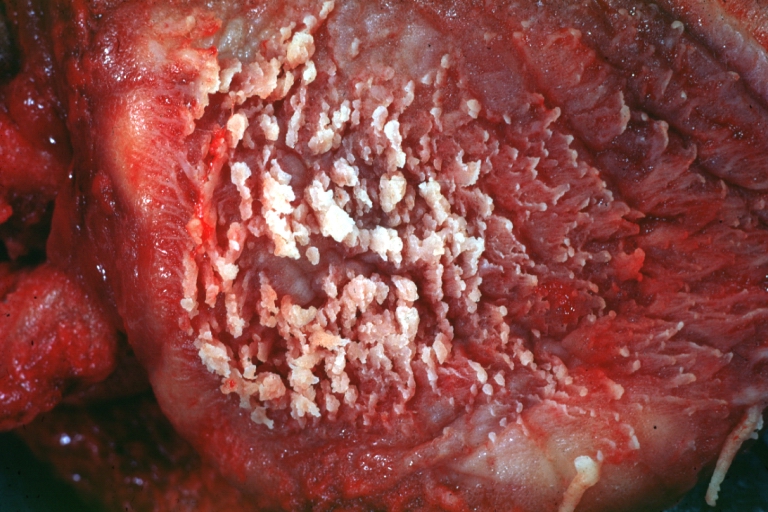

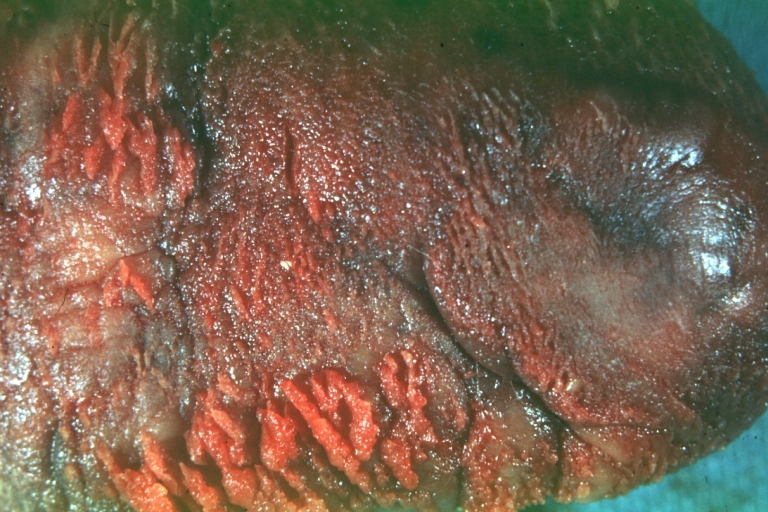

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example, close-up view of fibrin.

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example, close-up view.

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example.

-

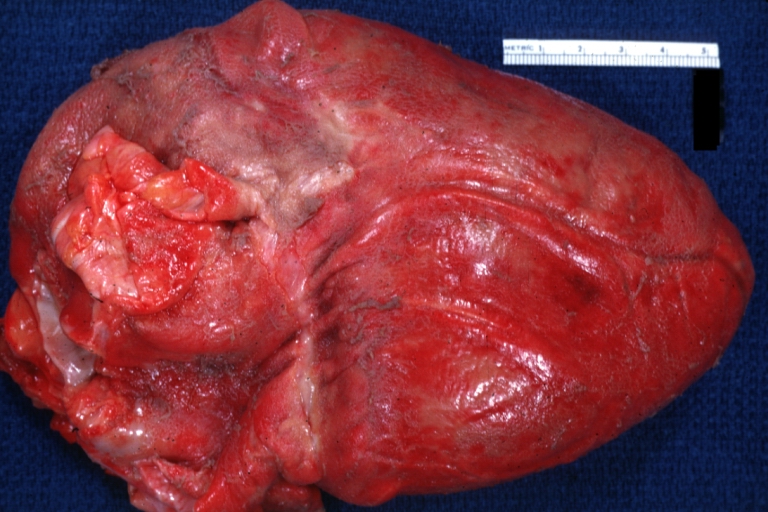

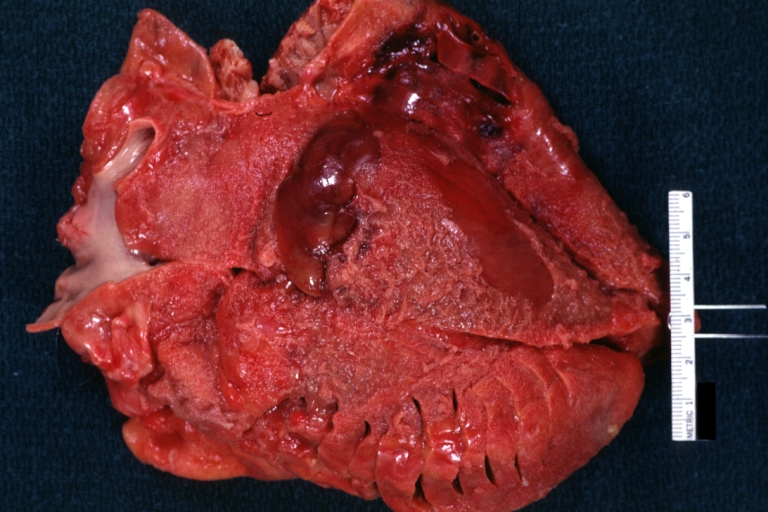

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, external view of localized pericarditis over an acute infarction

-

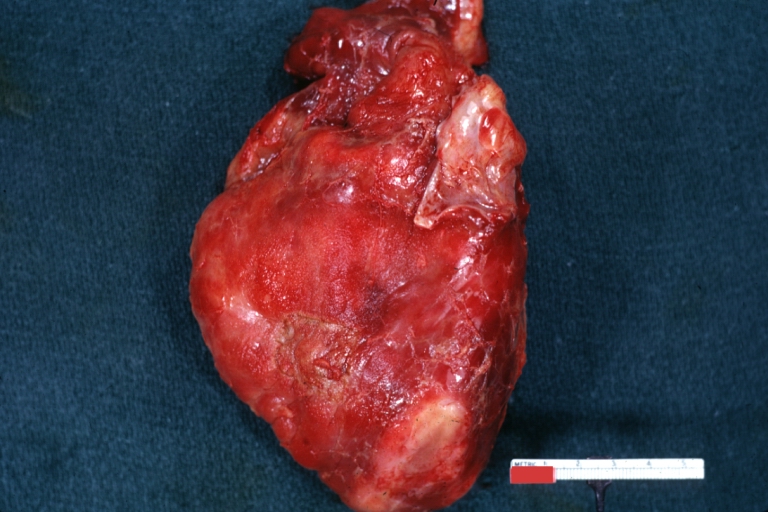

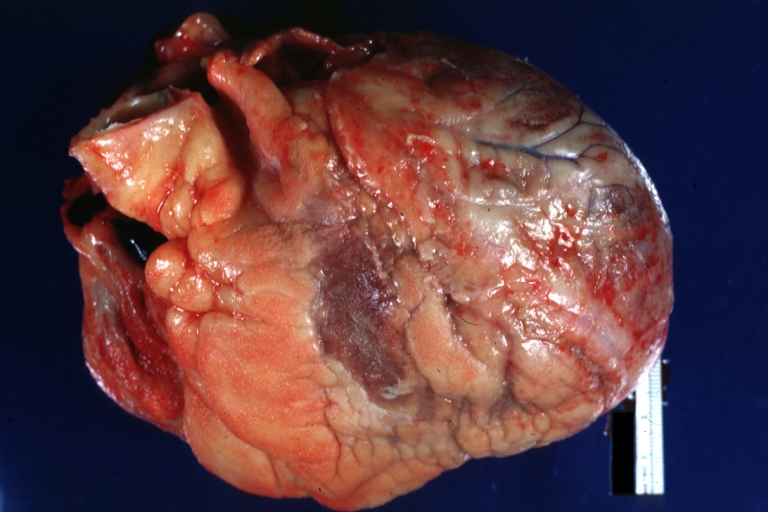

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, intact heart, good example

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, good example, mild, with small amount of fibrin

-

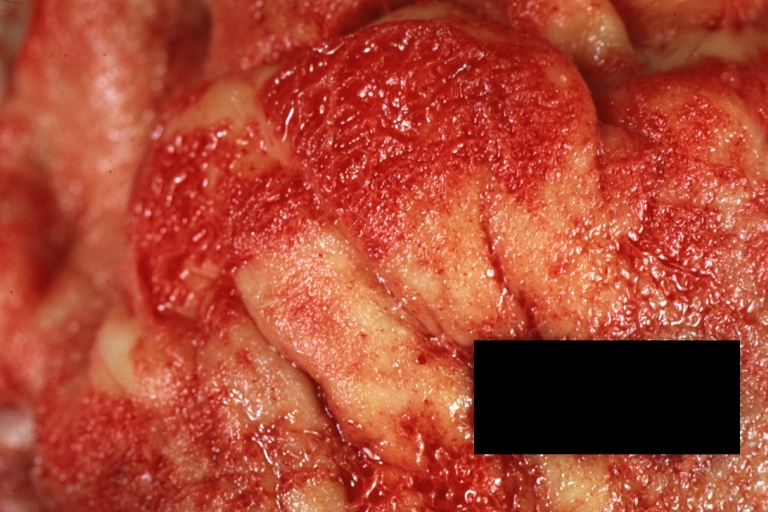

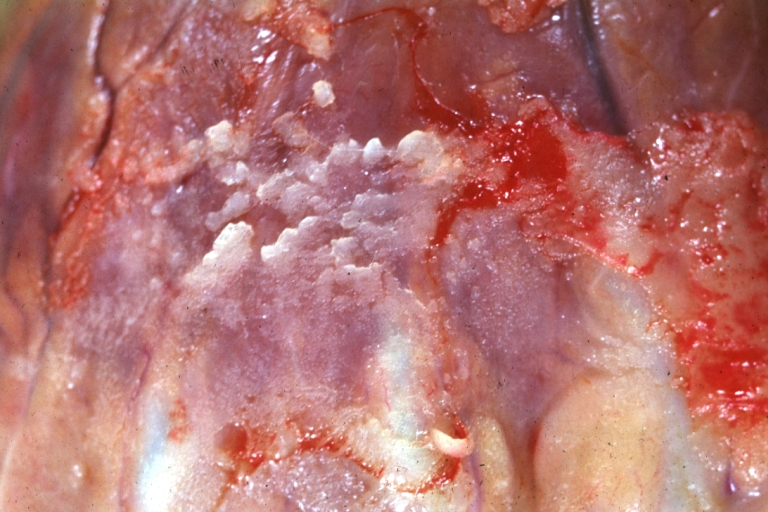

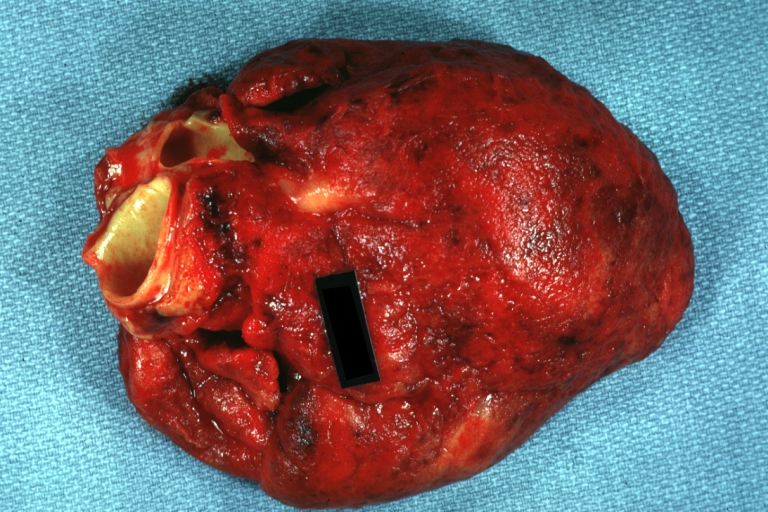

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, close-up, an excellent example of color and detail

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a good example

-

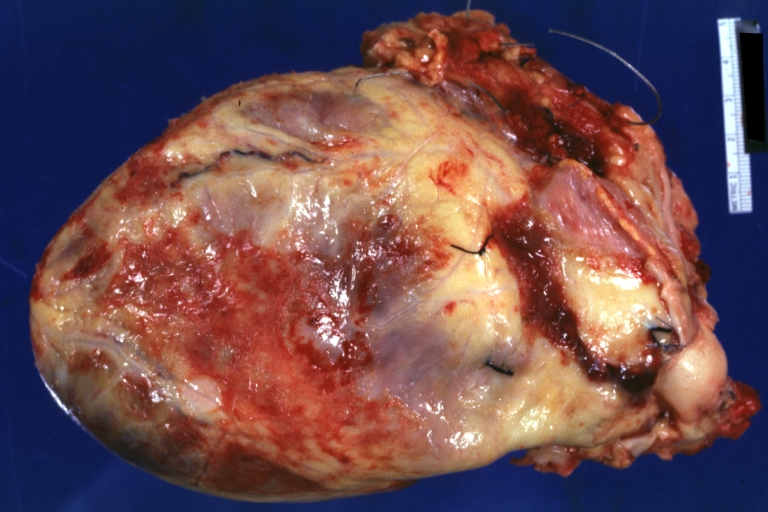

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a good example, very mild case

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example.

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a close-up view, an excellent illustration of fibrinous exudate.

-

Pericarditis in uremia

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, fixed tissue (note to color changes), a close-up view of fibrin on epicardial surface of heart. A typical example.

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, large right atrial thrombus and fibrinous pericarditis. Normal tricuspid valve with some aging changes (good example)

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, an excellent example

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, very close-up photo showing fibrinous exudate simulating frost (an excellent example)

-

Rheumatoid fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, a typical lesion in 22 years old white female due to juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, close-up view of minimal fibrinous exudate on epicardial surface due to terminal renal failure

-

Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, anterior view of heart with mild fibrinous exudate over epicardium due to terminal renal failure

-

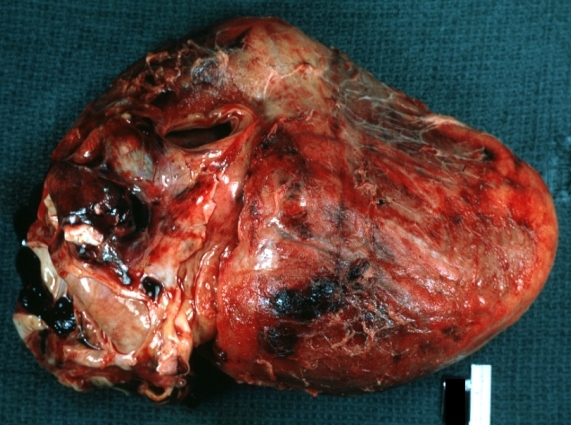

Tuberculous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, shaggy hemorrhagic exudate. This case is much more hemorrhagic than the typical tuberculous pericarditis.

-

Heart transplant: Gross, natural color, external view of heart. Two months after transplantation with fibrinous pericarditis

-

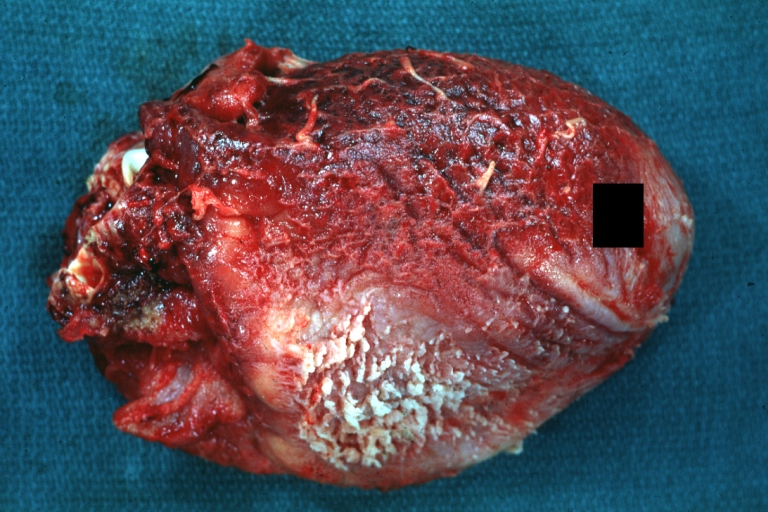

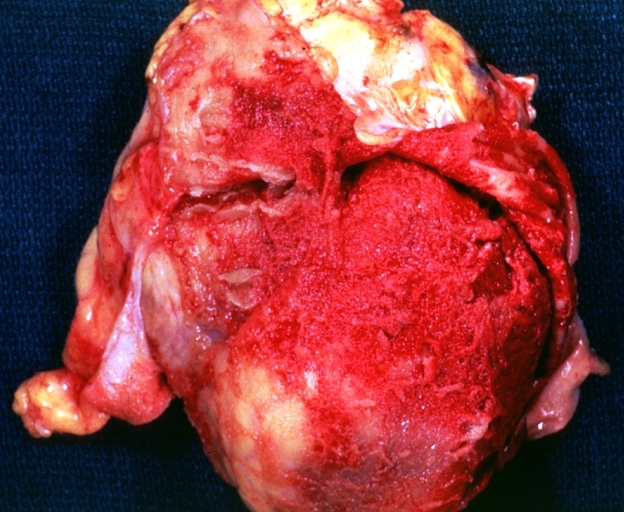

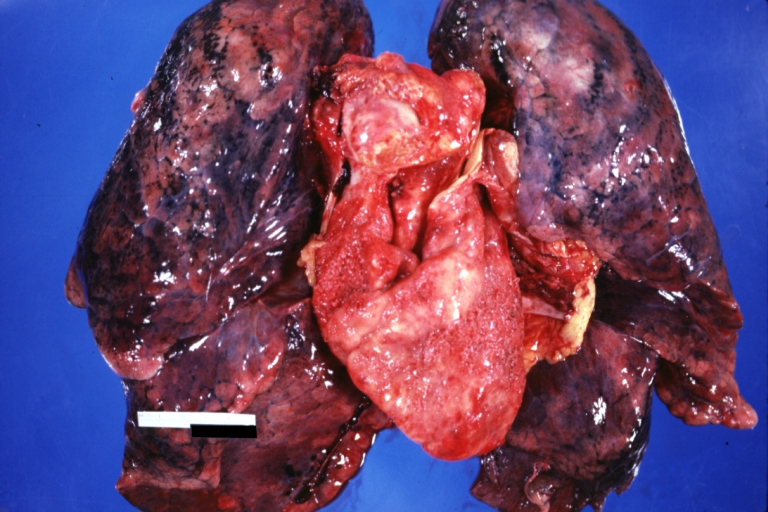

Neoplastic pericarditis: Gross, natural color, shaggy pericarditis. Primer is adenocarcinoma of the lung.

-

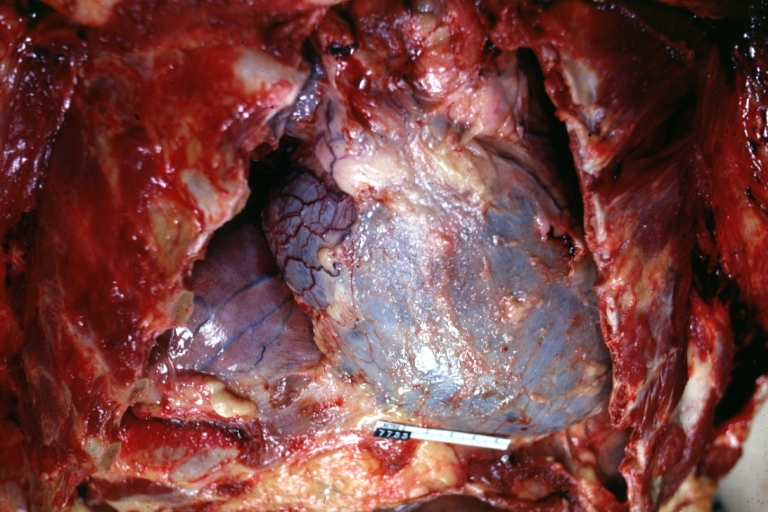

Heart: Septic pericarditis

-

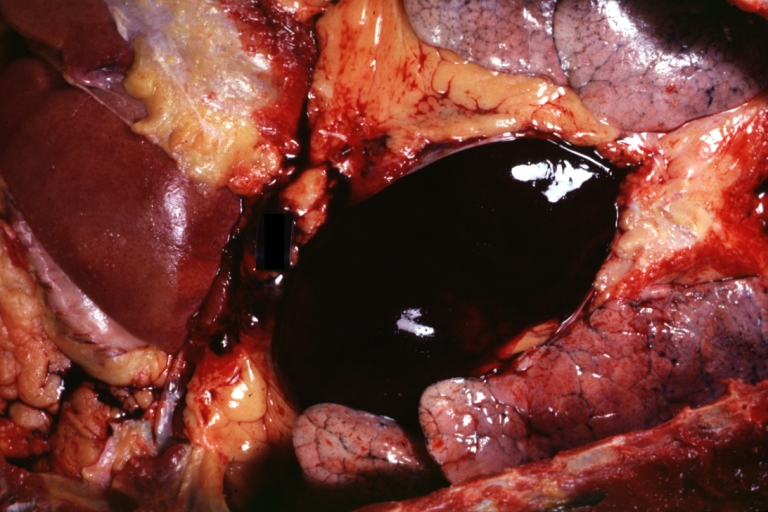

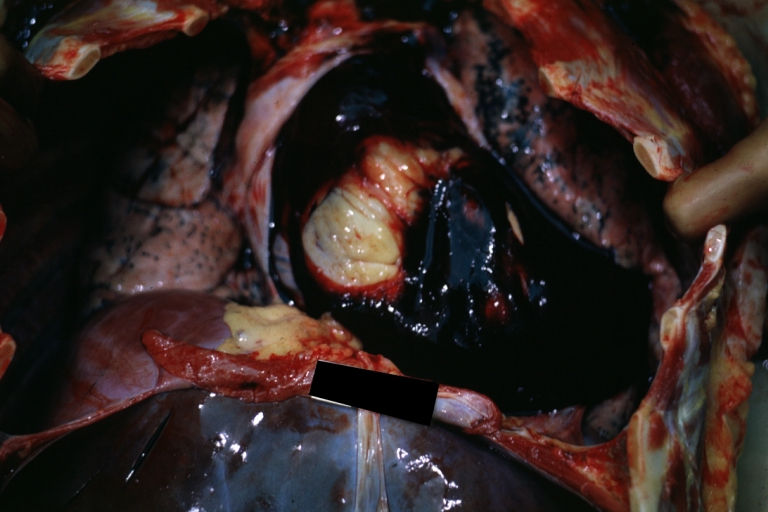

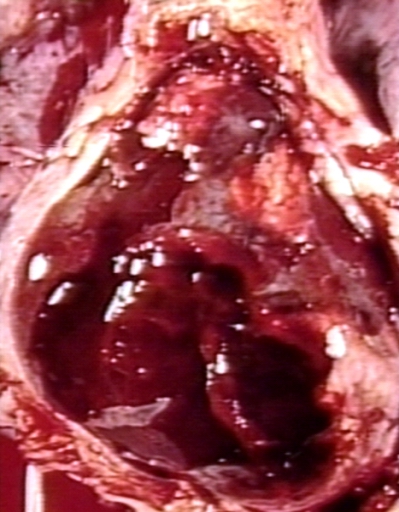

Hemopericardium: Gross, an excellent in situ view

-

Hemopericardium: Gross, in situ, unopened pericardium (a very good example)

-

Hemopericardium: Gross, natural color, heart in situ with opened pericardium and filled with red blood clot (quite good example) dissecting aneurysm

-

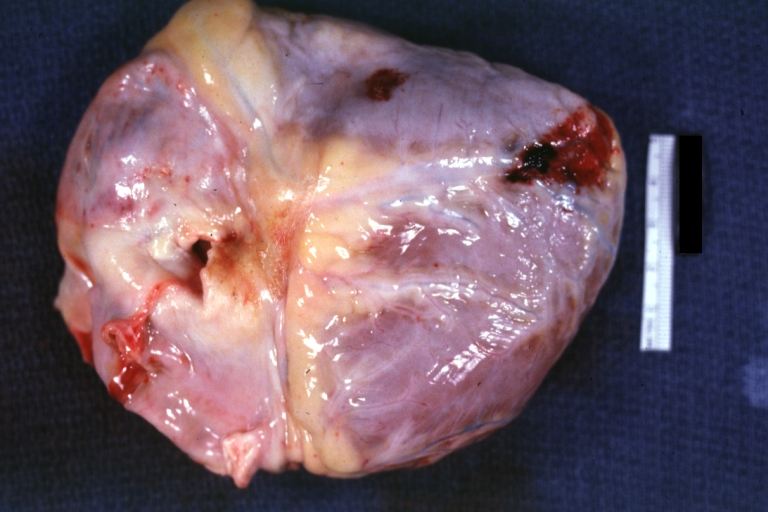

Hemopericardium due to Needle Puncture: Gross, natural color, external view of heart covered by blood

-

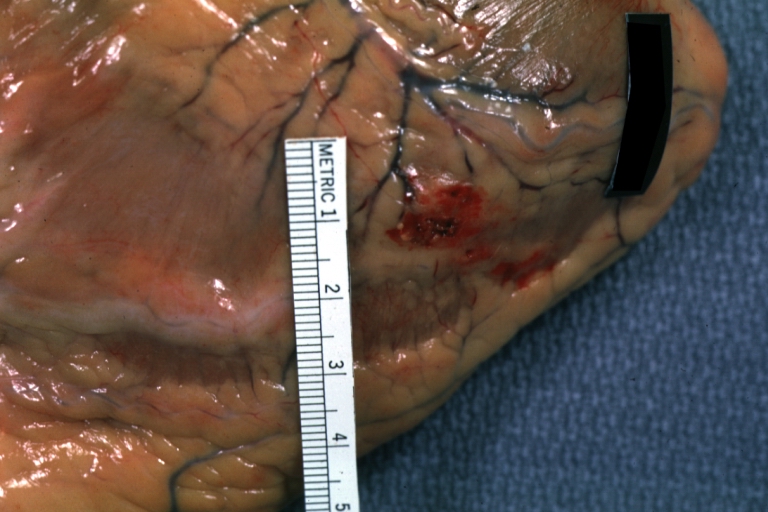

Needle Puncture Mark in Epicardium: Gross, natural color, close-up of needle puncture marks tap resulted in hemopericardium

-

Hemopericardium: Hemopericardium caused by pericardiocentesis: Gross, natural color, close-up view of apex of the heart. Needle apparently entered the distal posterior descending artery.

-

Hemopericardium: Hemopericardium caused by pericardiocentesis: Gross, natural color, view of apex of the heart. Needle apparently entered the distal posterior descending artery

-

Hemopericardium: Hemopericardium due to pericardiocentesis: Gross, fixed tissue, close-up view of slice through distal posterior descending artery showing periarterial hemorrhage

-

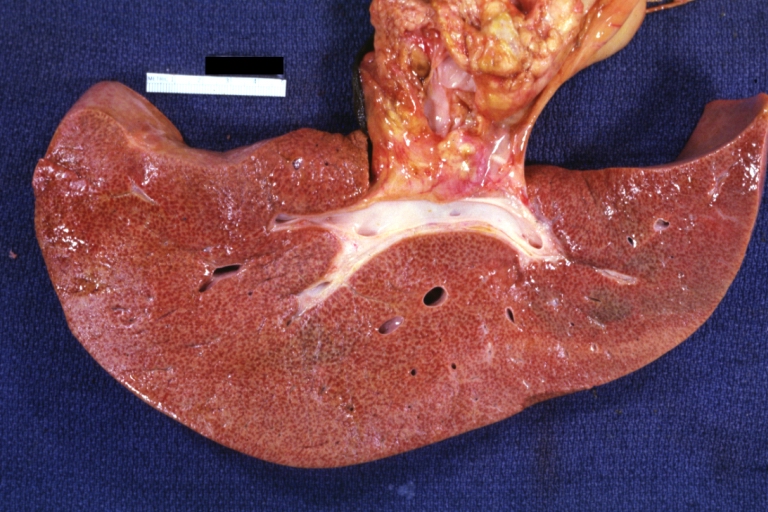

Hemopericardium: Liver: Gross, natural color, typical shock liver case of death due to hemopericardium secondary to pericardiocentesis

-

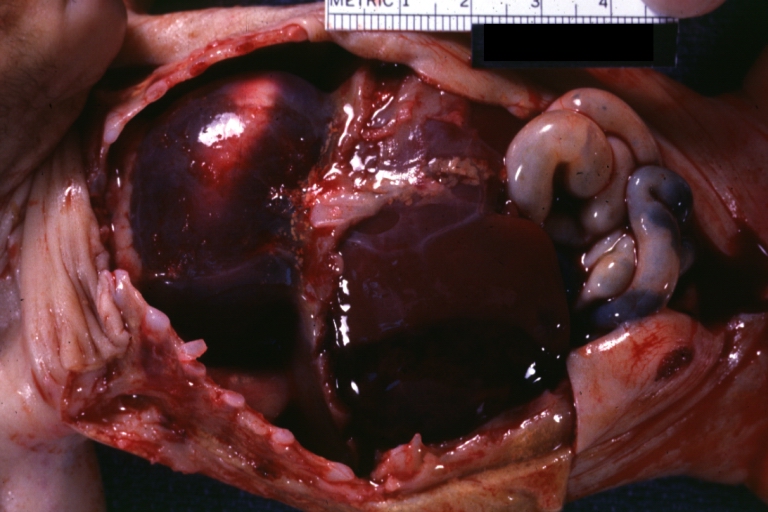

Hemopericardium in newborn: Gross, natural color, opened body with large collection blood in pericardial sac. Cause uncertain. A 26 week premature with hyaline membrane disease and DIC

-

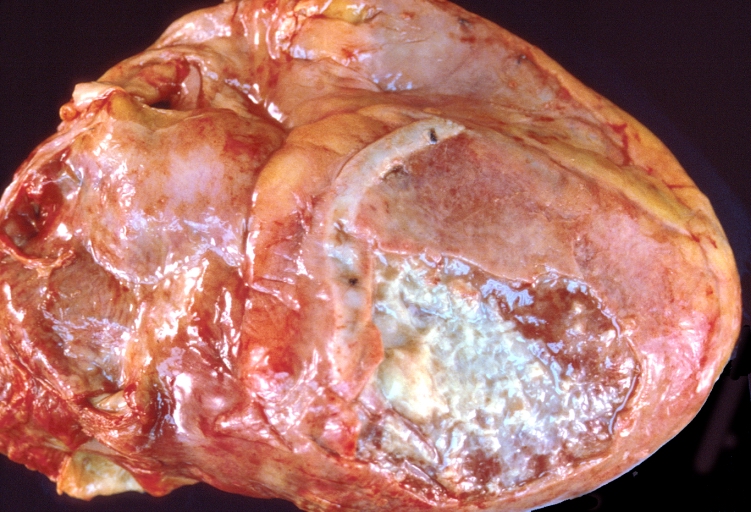

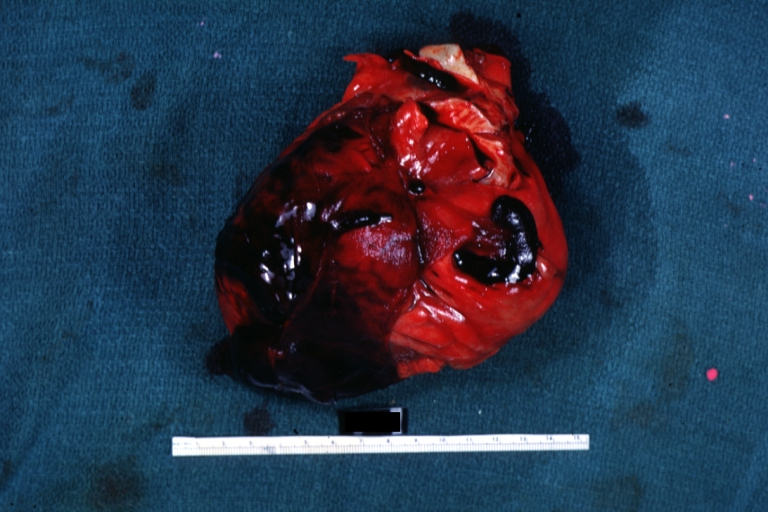

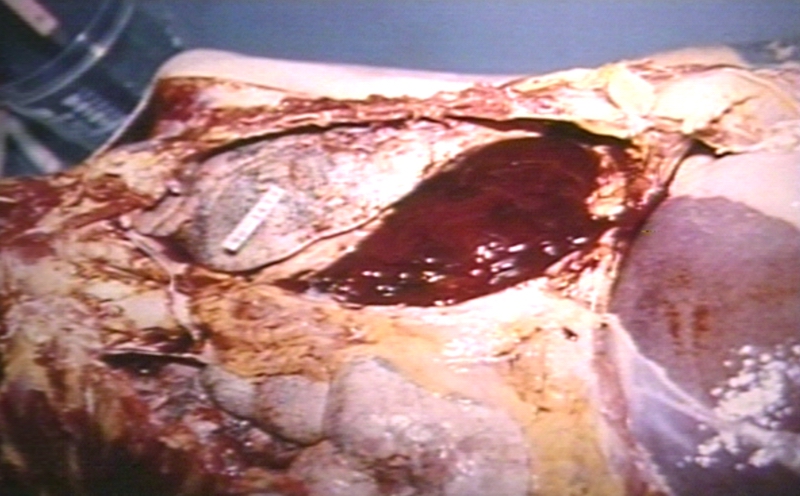

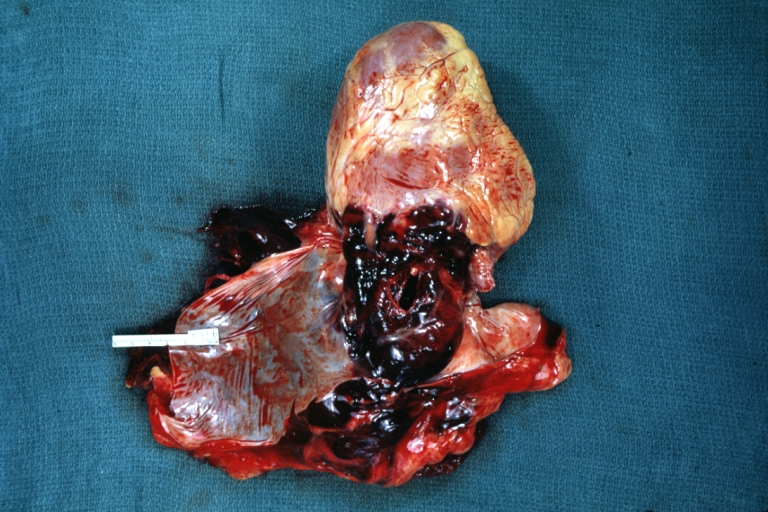

Hemopericardium: Myocardial Infarction and Ventricular Rupture

-

Hemopericardium: Infarct rupture after 7 days of chest pain onset.

-

Hemopericardium in dissecting aneurysm: Gross, heart with root of aorta to show hemorrhage into pericardium (very good example)

Microscopic Images

-

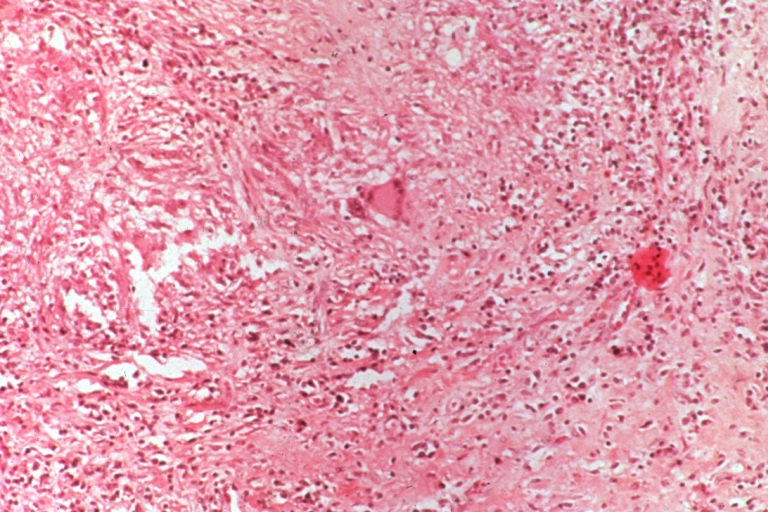

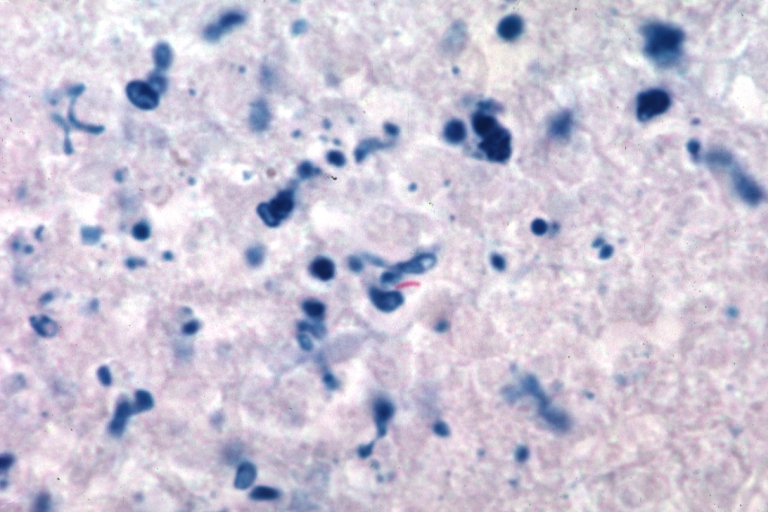

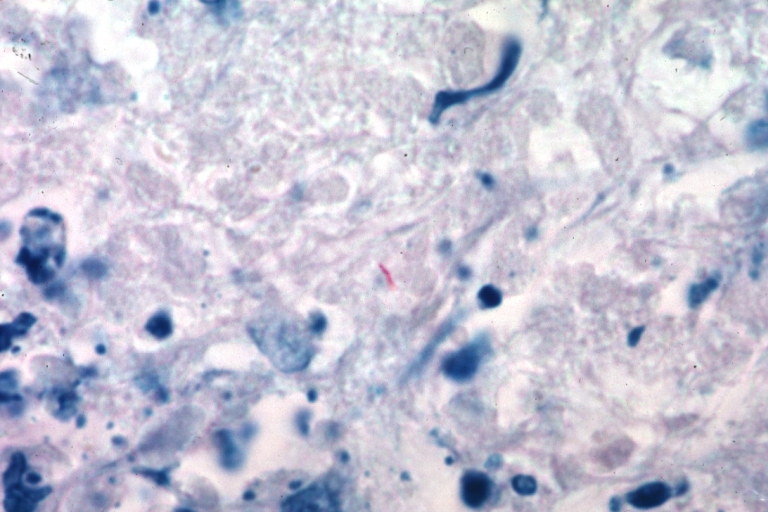

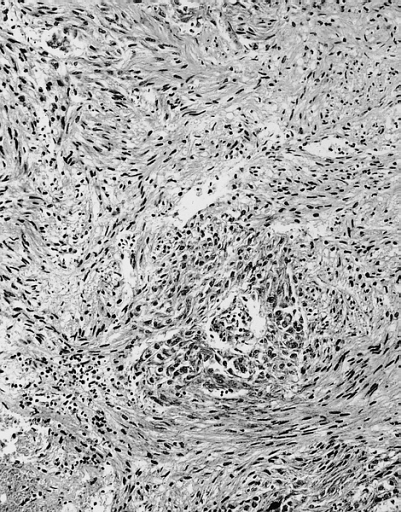

Tuberculous pericarditis.

-

Tuberculous pericarditis.

-

Tuberculous pericarditis: Micro oil acid fast stain. The organism easily seen.

-

Tuberculous pericarditis: Micro oil acid fast stain. The organism easily seen.

-

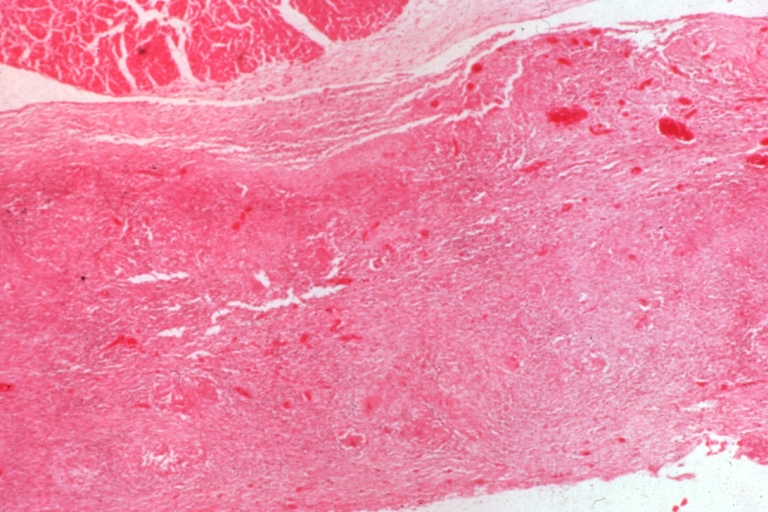

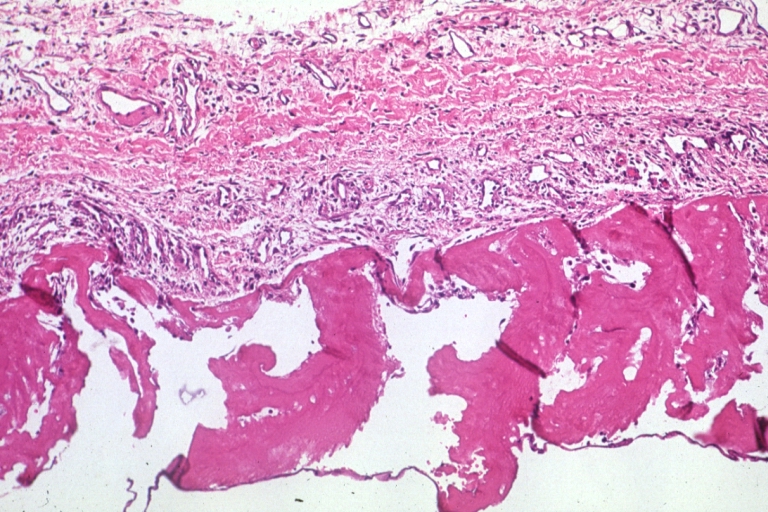

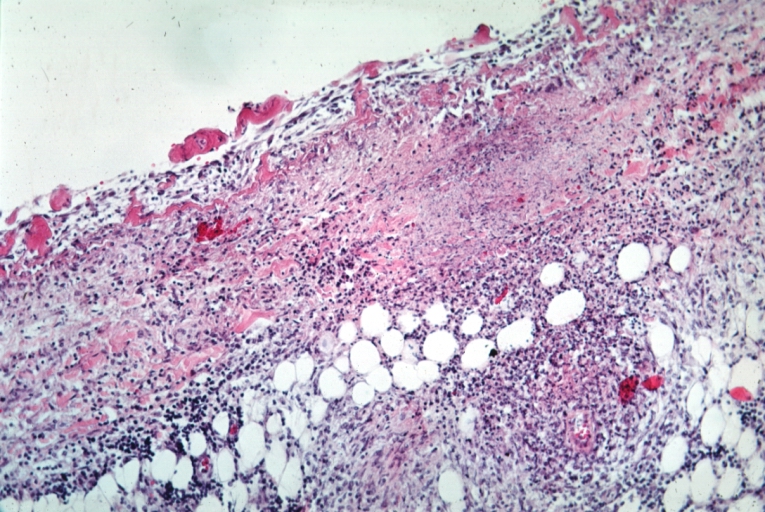

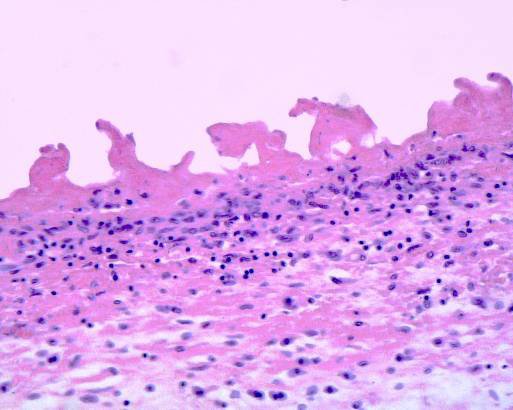

Uremic pericarditis: Micro med mag, H&E. A good example

-

Tuberculous pericarditis: Micro med mag, H&E, a typical lesion

-

Fibrinous pericarditis.

-

Pericarditis fibrinosa (Fibrinous pericarditis).

-

Malignant Mesothelioma, Biphasic Type: Pericardium: This tumor has epithelioid cells (lower half) surrounded by spindled cells. The patient was a 46-year-old woman with constrictive pericarditis; the pericardium was studded with coalescing tumor nodules.

- <Youtube v=AKS7kSl4x5k/>

- Acute fibrinous pericarditis

<Youtube v=5fz_W1YxbC8/>

Differential Diagnosis for Diseases of the Pericardium

Many other conditions produce signs and symptoms similar to those produced by pericarditis. Keep in mind that pericarditis might also be one of the following: "part of a generalized disease", "apparently isolated", or "part of a disease that affects a nearby organ", and "sometimes is the presenting syndrome of multiple diseases."

Key Signs & Symptoms to Differentiate Pericarditis:

- Pain on the trapezius ridge(s), is a pathognomonic of pericarditis. Often pain can radiate mimicking pain that is commonly felt during angina.

- Central pleuritic chest pain (can also be indicative of pleurisy; however, may be both)

- Pain that lasts longer, is sharper and unresponsive to vasodilator therapy (similar "to that of cardiac ischemia")

- Most acute pericarditis ECGs are similar to ECGs of ischemic heart disease rather than infarction

- Pulmonary embolism can present similarly to pericarditis, but can be differentiated from pericarditis in the presence of one of the following findings: a nonspecifically altered ECG, a plerual rub, and non-precordial (someitmes precordial pain is present regardless).

Acute Pericarditis

- Actinomycosis

- Acute idiopathic pericarditis

- Acute rheumatic fever

- Adenovirus

- Addison's crisis

- Amyloidosis

- Amebiasis

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Aortic dissection

- Behcet's Disease

- Borrelia

- Breast cancer

- Chylopericardium

- Coxsackie A

- Coxsackie B

- Cytomegalovirus

- Dermatomyositis

- Dermatosclerosis

- Dressler's Syndrome

- EBV

- ECHO virus

- Echinococcosis

- Familial Mediterranian Fever

- Francisella

- HIV

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Influenza virus

- Legionella

- Leukemia

- Lung cancer

- Lymphoma

- Meningococci

- Mixed Connective Tissue Disease

- Mumps virus

- Mycoplasma infection

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Perforated esophagus

- Pneumococci

- Polyarteritis Nodosa

- Polymyositis

- Postpericardiotomy syndrome

- Reiter's Syndrome

- Radiation therapy

- Renal Failure

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Rickettsia

- Sarcoidosis

- Scleroderma

- Serum sickness

- Staphylococci

- Streptococci

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Thorax trauma

- Treponema pallidum

- Toxoplasmosis

- Tuberculosis

- Uremia

- Varicella virus

- Wegener's granulomatosis

- Whipple's Disease

Chronic Pericarditis

- Amebiasis

- Bacterial infections

- Cholesterol pericarditis

- Chylopericardium

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Collagen Vascular Disease

- Coxsackie B

- Echinococcosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Neoplastic pericarditis

- Tuberculosis

- Uremic pericarditis

Treatment

The majority of patients with pericarditis are hospitalized so they can be observed and monitored for complications while they recover. The treatment of viral or idiopathic pericarditis is with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients should be observed for side effects since NSAIDs are known to effect the GI mucosa.

Severe cases of pericarditis may require:

Patients with uncomplicated acute pericarditis can generally be treated and followed up in an outpatient clinic. However, those with high risk factors for developing complications (see above) will need to be admitted to an inpatient service, most likely an ICU setting. High risk patients include:[10]

- subacute onset

- high fever (> 100.4 F) and leukocytosis

- development of cardiac tamponade

- large pericardial effusion (echo-free space > 20 mm) resistant to NSAID treatment

- immunocompromised

- history of oral anticoagulation therapy

- acute trauma

- failure to respond to seven days of NSAID treatment.

Usual Steps in Treatment of Pericarditis

Pericardiocentesis is a procedure whereby the fluid in a pericardial effusion is removed through a needle. It is performed under the following conditions:[11]

- presence of moderate or severe cardiac tamponade

- diagnostic purpose for suspected purulent, tuberculosis, or neoplastic pericarditis

- persistent symptomatic pericardial effusion

NSAIDs in viral or idiopathic pericarditis. In patients with underlying causes other than viral, the specific etiology should be treated. With idiopathic or viral pericarditis, NSAID is the mainstay treatment. Goal of therapy is to reduce pain and inflammation. The course of the disease may not be affected. The preferred NSAID is ibuprofen because of rare side effects, better effect on coronary flow, and larger dose range.[11] Depending on severity, dosing is between 300-800 mg every 6-8 hours for days or weeks as needed. An alternative protocol is aspirin 800 mg every 6-8 hours.[10] Dose tapering of NSAIDs may be needed. In pericarditis following acute myocardial infarction, NSAIDs other than aspirin should be avoided since they can impair scar formation. As with all NSAID use, GI protection should be engaged. Failure to respond to NSAIDs within one week (indicated by persistence of fever, worsening of condition, new pericardial effusion, or continuing chest pain) likely indicates that a cause other than viral or idiopathic is in process.

Colchicine can be used alone or in conjunction with NSAIDs in prevention of recurrent pericarditis and treatment of recurrent pericarditis. For patients with a first episode of acute idiopathic or viral pericarditis, they should be treated with an NSAID plus colchicine 1-2 mg on first day followed by 0.5 daily or BID for three months. [12][13][14]

Corticosteroids are usually used in those cases that are clearly refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine and a specific cause has not been found. Systemic corticosteroids are usually reserved for those with autoimmune disease.

Pharmacotherapy

Acute Pharmacotherapies

As previously mentioned, the typical pharmacotherapy in viral or idiopathic pericarditis is with NSAIDs. These drugs have analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory effects. The most prominent members of this group of drugs are aspirin and ibuprofen. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) has negligible anti-inflammatory activity.

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

Severe cases may require one of the aforementioned procedures or one of the alternative pharmacotherapies listed below:

- Antibiotics

- Steroids

Surgical and Device Based Therapies

Pericardiocentesis

A thoracoscopic approach to creating a pericardial window

A surgical subxiphoid incision to create a pericardial window

Pericardial Stripping for Constrictive Pericarditis

The definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis is pericardial stripping, which is a surgical procedure where the entire pericardium is peeled away from the heart. This may be effective in up to 50% of patients. This procedure has significant risk involved, since the thickened pericardium is often adherent to the myocardium and coronary arteries.

In patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery with pericardial sparing, there is danger of tearing a bypass graft while removing the pericardium. If any pericardium is not removed, it is possible for bands of pericardium to cause localized constriction which may cause symptoms and signs consistent with constriction.

Treatment Related Videos

- <youtube v=lJ6KzpnjbRg/>

Complications

Fibrinous pericarditis

Fibrinous pericarditis is an exudative inflammation. The pericardium is infiltrated by the fibrinous exudate. This consists of fibrin strands and leukocytes. Fibrin describes an amorphous, eosinophilic (pink) network. Leukocytes (mainly neutrophils) are found within the fibrin deposits and intrapericardic. Vascular congestion is also present. The myocardium has no changes. Sometimes referred to as having "Bread and Butter Appearance". Photo at: Atlas of Pathology

Pericarditis due to tuberculosis

Pericarditis caused by tuberculosis is difficult to diagnose, because definitive diagnosis requires culturing Mycobacterium tuberculosis from aspirated pericardial fluid or pericardial biopsy, which requires high technical skill and is often not diagnostic (the yield from culture is low even with optimum specimens).

The Tygerberg scoring system helps the clinician to decide whether pericarditis is due to tuberculosis or whether it is due to another cause:

- Night sweats (1 point),

- Weight loss (1 point),

- Fever (2 point),

- Serum globulin > 40g/l (3 points),

- Blood total leucocyte count <10 x 109/l (3 points);

A total score of 6 or more is highly suggestive of tuberculous pericarditis.[15]

Pericardial fluid with an interferon-γ level greater than 50pg/ml is highly specific for tuberculous pericarditis.

The definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis is pericardial stripping, which is a surgical procedure where the entire pericardium is peeled away from the heart. This procedure has significant risk involved,[16] with mortality rates of 6% or higher in major referral centers.[17][18] The high risk of the procedure is attributed to adherence of the thickened pericardium to the myocardium and coronary arteries. In patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery with pericardial sparing, there is danger of tearing a bypass graft while removing the pericardium.

References

- ↑ Maisch B, Ristic AD (2002). "The classification of pericardial disease in the age of modern medicine". Curr Cardiol Rep. 4 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1007/s11886-002-0121-6. PMID 11743917.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Spodick DH (2003). "Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice". JAMA. 289 (9): 1150–3. doi:10.1001/jama.289.9.1150. PMID 12622586.

- ↑ Karjalainen J, Heikkila J (1986). ""Acute pericarditis": myocardial enzyme release as evidence for myocarditis". Am Heart J. 111 (3): 546–52. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(86)90062-1. PMID 3953365.

- ↑ Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, Fatemi M, Chevalier P, Touboul P (2000). "Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis". Eur Heart J. 21 (10): 832–6. doi:10.1053/euhj.1999.1907. PMID 10781355.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E, Belli R, Ghisio A, Bobbio M, Trinchero R (2003). "Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis". J Am Coll Cardiol. 42 (12): 2144–8. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.02.001. PMID 14680742.

- ↑ Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL (2004). "Pericarditis". Lancet. 363 (9410): 717–27. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15648-1. PMID 15001332.

- ↑ Chotas HG, Dobbins JT, Ravin CE (1999) Principles of digital radiography with large-area, electronically readable detectors: a review of the basics. Radiology 210:595-599

- ↑ Higgins CB, De Roos A (2003) Cardiovascular MRI and MRA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

- ↑ Ohnesorge BM, Becker CR, Flohr TG, Reiser MF (2001) Multislice CT in cardiac imaging. Springer-Verlag

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, Giuggia M, Cecchi E, Gaschino G, Demarie D, Ghisio A, Trinchero R (2004). "Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy". J Am Coll Cardiol. 43 (6): 1042–6. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.055. PMID 15028364.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, Erbel R, Rienmuller R, Adler Y, Tomkowski WZ, Thiene G, Yacoub MH (2004). "Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology". Eur Heart J. 25 (7): 587–10. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002. PMID 15120056.

- ↑ Adler Y, Zandman-Goddard G, Ravid M, Avidan B, Zemer D, Ehrenfeld M, Shemesh J, Tomer Y, Shoenfeld Y (1994). "Usefulness of colchicine in preventing recurrences of pericarditis". Am J of Cardiol. 73 (12): 916–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(94)90828-1. PMID 8184826.

- ↑ Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Demichelis B, Pomari F, Moratti M, Gaschino G, Giammaria M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R (2005). "Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the COlchicine for acute PEricarditis (COPE) trial". Circulation. 112 (13): 2012–6. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542738. PMID 16186437.

- ↑ Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Pomari F, Moratti M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R (2005). "Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the CORE (COlchicine for REcurrent pericarditis) trial". Arch Intern Med. 165 (17): 1987–91. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.17.1987. PMID 16186468.

- ↑ Reuter H, Burgess L, van Vuuren W, Doubell A. (2006). "Diagnosing tuberculous pericarditis". Q J Med. 99: 827&ndash, 39. PMID 17121764.

- ↑ Cinar B, Enc Y, Goksel O, Cimen S, Ketenci B, Teskin O, Kutlu H, Eren E. (2006). "Chronic constrictive tuberculous pericarditis: risk factors and outcome of pericardiectomy". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 10 (6): 701–6. PMID 16776460.

- ↑ Chowdhury UK, Subramaniam GK, Kumar AS, Airan B, Singh R, Talwar S, Seth S, Mishra PK, Pradeep KK, Sathia S, Venugopal P (2006). "Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic evaluation of two surgical techniques". Ann Thorac Surg. 81 (2): 522–9. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.009. PMID 16427843.

- ↑ Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, Danielson GK, Mahoney DW, Seward JB, Tajik AJ (1999). "Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy". Circulation. 100 (13): 1380–6. PMID 10500037.

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D.

Additional Resources

Suggested Links and Web Resources

- Pericarditis - Mayo Clinic series

- Pericarditis - cardiologychannel.com

- Pericarditis information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- Pulsus paradoxus - Journal of Postgraduate Medicine

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pericarditis

- SeeMyHeart - Patient Information on Echocardiograms (Heart Ultrasounds)

- American Society of Echocardiography

- Stress Test with Echocardiography from Angioplasty.Org

- Echocardiography information from Children's Hospital Heart Center, Seattle.

- Coronary heart disease And echocardiography

- Echocardiography Resources Simple echocardiography tutorials

- Atlas of Echocardiography Echocardiography Database

- E-chocardiography Internet Journal of Cardiac Ultrasound

- Echobasics Basic introduction to echocardiography - German/Spanish English planned for 2007

- Echocardiography Basic information about echocardiography - HealthwoRx

For Patients

de:Perikarditis

nl:Pericarditis

sv:Hjärtsäcksinflammation