Nutcracker esophagus

| Nutcracker esophagus | |

| |

|---|---|

| Image courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted | |

| ICD-10 | K22.4 |

| ICD-9 | 530.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 32060 |

| MeSH | D015154 |

|

Nutcracker esophagus Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Nutcracker esophagus On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Nutcracker esophagus |

For patient information, click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Synonyms and keywords:: Diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker oesophagus, corkscrew esophagus.

Overview

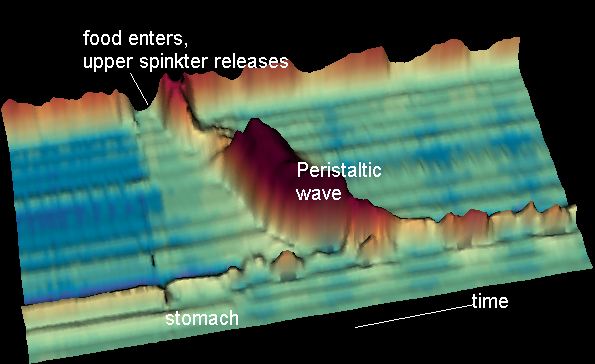

Nutcracker esophagus (diffuse esophageal spasm or corkscrew esophagus) is a disorder of the movement of the esophagus, and is one of many motility disorders of the esophagus, including achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm. It causes difficulty swallowing, or dysphagia, to both solid and liquid foods, and can cause chest pain; it may also have no symptoms. Nutcracker esophagus can affect people of any age, but is more common in the 6th and 7th decades of life. The diagnosis is made by an esophageal motility study, which evaluates the pressure of the esophagus at various points along its length. The term "nutcracker esophagus" comes from the finding of increased pressures during peristalsis, with a diagnosis made when pressures exceed 180 mmHg; this has been likened to the pressure of a mechanical nutcracker. The disorder does not progress, and is not associated with any complications; as a result, treatment of nutcracker esophagus targets control of symptoms only.[1]

Symptoms

Nutcracker esophagus is characterized as a motility disorder of the esophagus, meaning that it is caused by abnormal movement, or peristalsis of the esophagus.[1] Patients with motility disorders present with two key symptoms: either with chest pain (typically given termed as non-cardiac chest pain as it is esophageal in origin), which is usually found in disorders of spasm, or with dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing. Nutcracker esophagus can present with either of these, but chest pain is the more common presentation.[2] The symptoms of nutcracker esophagus are intermittent, and may occur with or without food.[1] Rarely patients can present with a sudden obstruction of the esophagus after eating food (termed a food bolus obstruction, or the steakhouse syndrome) requiring urgent treatment.[3][4] The disorder also does not progress to produce worsening symptoms or complications, unlike other motility disorders, such as achalasia, or anatomical abnormalities of the esophagus, such as peptic strictures or esophageal cancer.[5]

Many patients with nutcracker esophagus do not have any symptoms at all, as esophageal manometry studies done on patients without symptoms may show the same motility findings as nutcracker esophagus.[1][6]

Nutcracker esophagus may also be associated with the metabolic syndrome,[7] obesity,[8] and gastroesophageal reflux disease.[9] It is uncertain what the effects of treating the underlying conditions will have on improvement of symptoms.[10] The incidence of nutcracker esophagus in all patients is uncertain.

Diagnosis

In patients who have dysphagia, testing may first be done to exclude an anatomical cause of dysphagia, where there is a distortion of the anatomy of the esophagus. This usually includes visualization of the esophagus with an endoscope, and can also include barium swallow x-rays of the esophagus.[11] Endoscopy is typically normal in patients with nutcracker esophagus; however, abnormalities associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, which associates with nutcracker esophagus, may be seen.[9] Barium swallow in nutcracker esophagus is also typically normal.[1] Studies on endoscopic ultrasound show slight trend toward thickening of the muscularis propria of the esophagus in nutcracker esophagus, but this is not useful in making the diagnosis.[12]

Esophageal motility studies

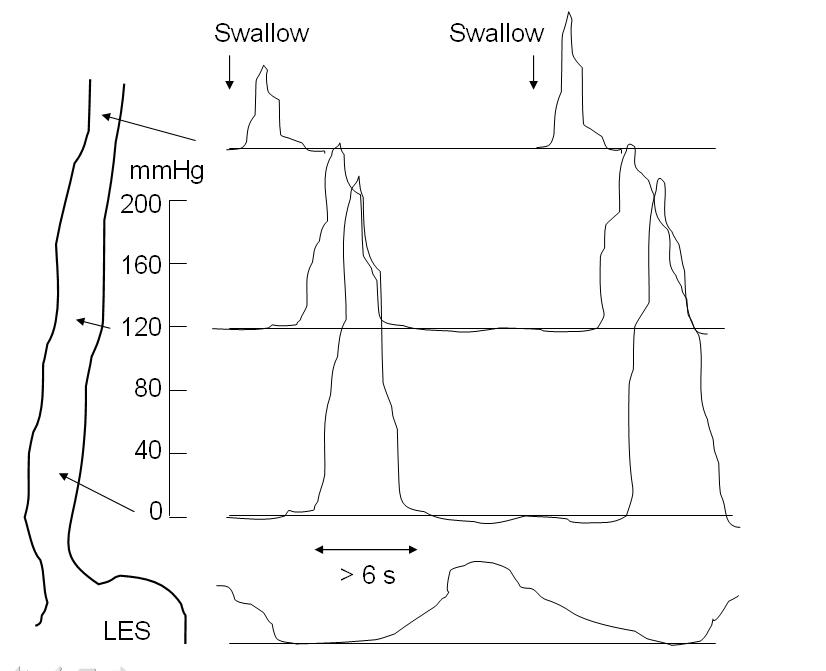

The diagnosis of nutcracker esophagus is typically made with an esophageal motility study, which shows characteristic features of the disorder. Esophageal motility studies involve pressure measurements of the esophagus after a patient takes a wet (fluid-containing) or dry (food-containing) swallow. Measurements are usually taken at various points in the esophagus.[11]

Nutcracker esophagus is characterized by a number of criteria described in the literature. The most commonly used criteria are the Castell criteria, named after American gastroenterologist D.O. Castell. The Castell criteria include one major criterion: a mean peristaltic amplitude in the distal esophagus of more than 180 mm Hg. The minor criterion is the presence of repetitive contractions (meaning 2 or more) that are greater than six seconds in duration. Castell also noted that the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes normally in nutcracker esophagus, but has an elevated pressure of greater than 40 mm Hg at baseline.[1] [11] [13][14]

Three other criteria for definition of the nutcracker esophagus have been defined. The Gothenburg criterion consists of the presence of peristaltic contractions, with an amplitude of 180 mm Hg at any place in the esophagus.[9][14] The Richter criterion involves the presence of peristaltic contractions with an amplitude of greater than 180 mmHg from an average of measurements taken 3 and 8 centimetres above the lower esophageal sphincter.[15] It has been incorporated into a number of clinical guidelines for the evaluation of dysphagia.[14] The Achem criteria are more stringent criteria that are an extension of the study of 93 patients used by Richter and Castell in the development of their criteria, and require amplitudes of greater than 199 mm Hg at 3 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), greater than 172 mm Hg at 8 cm above the LES, or greater than 102 mm Hg at 13 cm above the LES.[14][16]

Esophagography

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted

Pathophysiology

Pathology specimens of the esophagus in patients with nutcracker esophagus show no significant abnormality, unlike patients with achalasia where destruction of the myenteric plexus is seen. This has led to the thought the the pathophysiology of nutcracker esophagus may be related to abnormalities in neurotransmitters or other mediators in the distal esophagus. Abnormalities in nitric oxide levels, which have been seen in achalasia are postulated as the primary abnormality.[1][17] As GERD is associated with nutcracker esophagus, it has also been hypothesized that the alterations in nitric oxide and other released chemicals may be response to reflux.[14]

Treatment

Nutcracker esophagus is a benign, non-progressive condition, meaning that it is not associated with significant complications. Patients are usually reassured by their physicians that the disease is not associated with worsening. However, the symptoms of chest pain and dysphagia may be severe enough to require treatment with medications, and, rarely, surgery.

The first step in treatment of nutcracker esophagus is the reduction of risk factors. While weight reduction may be useful in reducing symptoms, the role of acid suppression therapy to reduce esophageal reflux, is still uncertain.[10]

Medical therapy for nutcracker esophagus includes the use of calcium-channel blockers, which relax the LES and palliate the dysphagia symptoms. Diltiazem has been used in randomized control studies with good effect.[18] Nitrate medications, including isosorbide dinitrate, given before meals may also help relax the LES and improve symptoms.[1] Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, such as sildenafil have also been tried in case series for treatment.[1] Finally, trazodone, an anti-depressant that reduces visceral sensitivity, has also been shown to reduce chest pain symptoms in patients with nutcracker esophagus.[1][19][17]

Endoscopic therapy with botulinum toxin, known also as Botox, can also be used to temporarily improve symptoms,[20] but the effect is temporarily and may only last for weeks. Finally, pneumatic dilatation of the esophagus, which is an endoscopic technique where a high-pressure balloon is used to stretch the muscles of the LES, can be performed to improve symptoms.[1][17]

In patients who have no response to medical or endoscopic therapy, surgery can be performed. A Heller myotomy involves an incision to disrupt the LES and the myenteric plexus that innervates it. It is used as a final treatment option in patients who do not respond to other therapies.[1][21][22]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Tutuian R, Castell D (2006). "Esophageal motility disorders (distal esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, and hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter): modern management". Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 9 (4): 283–94. PMID 16836947.

- ↑ Fass R, Dickman R (2006). "Nutcracker esophagus--a nut hard to swallow". J Clin Gastroenterol. 40 (6): 464–6. PMID 16825926.

- ↑ Breumelhof R, Van Wijk H, Van Es C, Smout A (1990). "Food impaction in nutcracker esophagus". Dig Dis Sci. 35 (9): 1167–71. PMID 2390932.

- ↑ Chae H, Lee T, Kim Y, Lee C, Kim S, Han S, Choi K, Chung I, Sun H (2002). "Two cases of steakhouse syndrome associated with nutcracker esophagus". Dis Esophagus. 15 (4): 330–3. PMID 12472482.

- ↑ Dalton C, Castell D, Richter J (1988). "The changing faces of the nutcracker esophagus". Am J Gastroenterol. 83 (6): 623–8. PMID 3376915.

- ↑ Adler D, Romero Y (2001). "Primary esophageal motility disorders". Mayo Clin Proc. 76 (2): 195–200. PMID 11213308.

- ↑ Börjesson M, Albertsson P, Dellborg M, Eliasson T, Pilhall M, Rolny P, Mannheimer C (1998). "Esophageal dysfunction in syndrome X.". Am J Cardiol. 82 (10): 1187–91. PMID 9832092.

- ↑ Hong D, Khajanchee Y, Pereira N, Lockhart B, Patterson E, Swanstrom L. "Manometric abnormalities and gastroesophageal reflux disease in the morbidly obese". Obes Surg. 14 (6): 744–9. PMID 15318976.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Fang J, Bjorkman D (2002). "Nutcracker esophagus: GERD or an esophageal motility disorder". Am J Gastroenterol. 97 (6): 1556–7. PMID 12094884.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Borjesson M, Rolny P, Mannheimer C, Pilhall M (2003). "Nutcracker oesophagus: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of the effects of lansoprazole". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 18 (11–12): 1129–35. PMID 14653833.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Cockeram A (1998). "Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Practice Guidelines: evaluation of dysphagia". Can J Gastroenterol. 12 (6): 409–13. PMID 9784896.

- ↑ Melzer E, Ron Y, Tiomni E, Avni Y, Bar-Meir S (1997). "Assessment of the esophageal wall by endoscopic ultrasonography in patients with nutcracker esophagus". Gastrointest Endosc. 46 (3): 223–5. PMID 9378208.

- ↑ Ott D (1994). "Motility disorders of the esophagus". Radiol Clin North Am. 32 (6): 1117–34. PMID 7972703.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Pilhall M, Börjesson M, Rolny P, Mannheimer C (2002). "Diagnosis of nutcracker esophagus, segmental or diffuse hypertensive patterns, and clinical characteristics". Dig Dis Sci. 47 (6): 1381–8. PMID 12064816.

- ↑ Richter J, Wu W, Johns D, Blackwell J, Nelson J, Castell J, Castell D (1987). "Esophageal manometry in 95 healthy adult volunteers. Variability of pressures with age and frequency of "abnormal" contractions". Dig Dis Sci. 32 (6): 583–92. PMID 3568945.

- ↑ Achem S, Kolts B, Burton L (1993). "Segmental versus diffuse nutcracker esophagus: an intermittent motility pattern". Am J Gastroenterol. 88 (6): 847–51. PMID 8503378.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kahrilas P (2000). "Esophageal motility disorders: current concepts of pathogenesis and treatment". Can J Gastroenterol. 14 (3): 221–31. PMID 10758419.

- ↑ Cattau E, Castell D, Johnson D, Spurling T, Hirszel R, Chobanian S, Richter J (1991). "Diltiazem therapy for symptoms associated with nutcracker esophagus". Am J Gastroenterol. 86 (3): 272–6. PMID 1998307.

- ↑ Achem S, Kolts B (1992). "Current medical therapy for esophageal motility disorders". Am J Med. 92 (5A): 98S–105S. PMID 1595773.

- ↑ Tutuian R, Castell D (2006). "Esophageal motility disorders (distal esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, and hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter): modern management". Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 9 (4): 283–94. PMID 16836947.

- ↑ Traube M, Tummala V, Baue A, McCallum R (1987). "Surgical myotomy in patients with high-amplitude peristaltic esophageal contractions. Manometric and clinical effects". Dig Dis Sci. 32 (1): 16–21. PMID 3792178.

- ↑ Richter J, Castell D (1987). "Surgical myotomy for nutcracker esophagus. To be or not to be?". Dig Dis Sci. 32 (1): 95–6. PMID 3792184.