Neuroendocrine tumors: Difference between revisions

Sara Mohsin (talk | contribs) |

Sara Mohsin (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 496: | Line 496: | ||

===Metastases and malignancy=== | ===Metastases and malignancy=== | ||

* In the context of GEP-NETs, the terms ''[[metastatic]]'' and ''[[malignant]]'' are often used interchangeably. | * In the context of GEP-[[NET1|NETs]], the [[Term logic|terms]] ''[[metastatic]]'' and ''[[malignant]]'' are often [[Usage analysis|used]] interchangeably. | ||

* GEP-NETs are often malignant, since the primary site often eludes detection for years, sometimes decades – during which time the tumor has the opportunity to metastasize. | * GEP-[[NET1|NETs]] are often [[malignant]], since the primary site often eludes [[Detection theory|detection]] for [[Year|years]], sometimes decades – during which [[Time constant|time]] the [[tumor]] has the opportunity to [[metastasize]]. | ||

* Researchers differ widely in their estimates of malignancy rates, especially at the level of the secretory subtypes (the various "-omas"). | *[[Research|Researchers]] [[Difference (philosophy)|differ]] [[Wide and fast|widely]] in their [[Estimate|estimates]] of [[malignancy]] [[rates]], especially at the [[Level of measurement|level]] of the [[Secretory component|secretory]] subtypes (the various "-omas"). | ||

* The most common metastatic sites are the liver, the lymph nodes, and the bones. | * The most common [[metastatic]] sites are the [[liver]], the [[lymph nodes]], and the [[bones]]. | ||

* Liver metastases are so frequent and so well-fed that for many patients, they dominate the course of the [[Cancer (disease)|cancer]]. | *[[Liver]] [[metastases]] are so [[Frequentist|frequent]] and so [[WellPoint|well]]-fed that for many [[patients]], they dominate the [[Course (medicine)|course]] of the [[Cancer (disease)|cancer]]. | ||

* For a patient with a nonsecretory PET, for example, the primary threat to life may be the sheer bulk of the tumor load in the liver. | * For a [[patient]] with a nonsecretory [[PET]], for [[Example 1|example]], the primary threat to [[life]] may be the sheer bulk of the [[tumor]] [[Loading dose|load]] in the [[liver]]. | ||

==Causes== | ==Causes== | ||

Revision as of 16:38, 16 September 2019

| Neuroendocrine tumors | |

| ICD-9 | 209 |

|---|---|

| ICD-O: | M8013/3, M8041/3, M8246/3, M8247/3, M8574/3 |

| MedlinePlus | 000393 |

| MeSH | D018358 |

|

Neuroendocrine tumors Microchapters |

For patient information, click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [12] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Sara Mohsin, M.D.[13]

Overview

Neuroendocrine tumors, or more properly gastro-entero-pancreatic or gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs), are cancers of the interface between the endocrine (hormonal) system and the nervous system.

Historical Perspective

- In 1907, Siegfried Oberndorfer was the first person to clearly distinguish GEP-NETs from other forms of cancer. Since they were so slow-growing, he considered them to be "cancer-like" rather than truly cancerous, and hence, he coined the term "carcinoid" for these tumors.

- In 1929, Siegfried Oberndorfer reported that some such tumors were not so indolent and distinguished them as PETs (mostly called carcinoids). Despite of the differences between the two categories, even in the twenty-first century, some doctors (including oncologists) insist on calling all GEP-NETs "carcinoid".

- In 1988, the earliest synthetic form of somatostatin used in the treatment of Neuroendocrine tumors was octreotide, which was first marketed by Sandoz as Sandostatin.

- In 2006 and 2007, the European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) proposed a staging scheme same as for most other types of epithelial neoplasms for GEP NENs, alongwith a histologic grading system applicable to all disease stages. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) later on endorsed this grading proposal for the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging classification of digestive system NENs, after modifying the staging parameters of the ENETS proposal.

- Th 2010 WHO classification of tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and pancreas (which was subsequently updated in 2017) also endorsed the ENETS grading scheme for NENs of the digestive tract, separating well-differentiated tumors into low-grade (G1) and intermediate-grade (G2) categories. All poorly differentiated NETs are high-grade (G3) NECs according to this classification scheme.

Classification

Human GEP-NETs by Site of Origin and by Symptom

| Human GEP-NETs by Site of Origin and by Symptom | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Carcinoids (about two thirds of GEP-NETs) |

|

|

|

| |

| PETs (about one third of GEP-NETs) |

|

|

|

| |

| Rare GEP-NETs |

|

|

Simplified classification according to anatomic distribution

| Involved organ | Name/type of neuroendocrine tumor |

|---|---|

| Pituitary gland |

|

| Thyroid gland |

|

| Parathyroid glands |

|

| Thymus and mediastinum |

|

| Lungs |

|

| Extrapulmonary |

|

| GIT |

|

| Adrenal gland |

|

| Peripheral nervous system | Peripheral nervous system tumors, such as:

|

| Mammary gland |

|

| Genitourinary tract |

|

| Skin |

|

| Multiple organs involvement in inherited conditions |

|

Classification of GEP-NETs by cell characteristics

- The diverse and amorphous nature of GEP-NETs has led to a confused, overlapping, and changing terminology.

- In general, aggressiveness (malignancy), secretion (of hormones), and anaplasia (dissimilarity between tumor cells and normal cells) tend to go together, but there are many exceptions, which have contributed to the confusion in terminology. For example, the term atypical carcinoid is sometimes used to indicate an aggressive tumor without secretions, whether anaplastic or well-differentiated.

- In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) revised the classification of GEP-NETs, abandoning the term carcinoid in favor of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) and abandoning islet cell tumor or pancreatic endocrine tumor for neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC).

- Judging from papers published into 2006, the medical community is accepting this new terminology with great sluggishness. (Perhaps one reason for the resistance is that the WHO chose to label the least aggressive subclass of neuroendocrine neoplasm with the term – neuroendocrine tumor – widely used previously either for the superclass or for the generally aggressive noncarcinoid subclass.)

- Klöppel et alia have written an overview that clarifies the WHO classification and bridges the gap to the old terminology (Klöppel, Perren, and Heitz 2004), this old terminology is given in the table below:

Summary of classification by cell characteristics (the WHO classification)

- GEP-NETs are also sometimes called APUDomas, but that term is now considered to be misleading, since it is based on a discredited theory of the development of the tumors[1]

| Superclass:Öberg, WHO, Klöppel et alia: Gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (GEP-NET) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subclass 1 (less malignant) | Subclass 2 (more malignant) | Subclass 3 (most malignant) | Subclass 4 (mixed) | Subclass 5 (miscellaneous) |

|

|

|

|

|

2010 WHO Classification Of NET

- 2010 WHO Classification Of neuroendocrine tumors with their ICD-O-3 codes is given below:

| NET (Neuroendocrine Tumor) Classification | Location | ICD-O-3 Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NET G1 (Grade 1) | All organs | 8240/3 | |

| NET G2 (Grade 2) | All organs | 8249/3 | |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | All organs | 8246/3 | |

| Large cell NEC | All organs | 8013/3 | |

| Small cell NEC | All organs | 8041/3 | |

| Enterochromaffin cell serotonin-producing NET | All organs | 8241/3 | |

| Gastrin-producing NET (gastrinoma) | Stomach, ampulla, small intestine, pancreas | 8153/3 | |

| Glucagon-producing NET (glucagonoma) | Pancreas | 8152/3 | |

| Gangliocytic paraganglioma | Ampulla, small intestine | 8683/0 | |

| Somatostatin-producing NET (somatostatinoma) | Ampulla, small intestine, pancreas | 8156/3 | |

| Insulin-producing NET (insulinoma) | Pancreas | 8151/3 | |

| VIPoma | Pancreas | 8155/3 | |

| L cell, Glucagon-like peptide and PP/PYY-producing NETs | Small intestine, appendix, colorectum | 8152/1 | |

| Goblet cell carcinoid | Appendix, extrahepatic bile duct | 8241/3 | |

| Tubular carcinoid | Appendix, extrahepatic bile duct | 8245/1 | |

| Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) | All organs | 8244/3 | |

| Neuroendocrine microadenoma | Pancreas | 8150/0 | |

WHO Grading criteria for neuroendocrine neoplasms

- WHO grading criteria for neuroendocrine neoplasms is based upon histological markers for cellular proliferation (rather than cellular polymorphism)

- Following table shows the currently recommended WHO garding criteria for all gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms:[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][3][6][9]

| Grade/Classification | Mitotic Count/ 10 HPFs (High-Power Field) | Ki-67 Labeling Index, % | Traditional |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine neoplasm GX | Grade cannot be assessed | ||

| Well-differentiated GIT NETs & PanNENs: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) | |||

| Neuroendocrine tumor, Grade 1 and PanNET G1 (low grade) | <2 | <3 |

|

| Neuroendocrine tumor, Grade 2 and PanNET G2 (intermediate grade) | 2–20 | 3–20 |

|

| PanNET G3 | >20 | >20 | _ |

| Poorly differentiated PanNENs: Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas (PanNECs) | |||

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma, Grade 3 and

PanNEC G3 (high grade) |

>20 | >20 | Small cell carcinoma |

| Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | |||

| Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN) | |||

| Classification | I | II | III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence, % | 55–88 | 8–13 | 12–23 |

| Multifocality | Multiple | Multiple | Single |

| Peritumoral oxyntic mucosa | Atrophic | Hypertrophic | Normal |

| Size, cm | 0.5–1 | <2 | >2 |

| Location | Corpus | Corpus | Any |

| Sex | M < F | M = F | M > F |

| Hypergastrinemia | Yes | Yes | No |

| Antral G-cell hyperplasia | Yes | No | No |

| Associated disease |

|

|

No |

| Precursor lesion | Yes | Yes | No |

| WHO 2010 classification | Grade 1 | Grades 1 or 2 | Grades 1–3 |

| Lymph node metastasis, % | 5 | 30 | 70 |

| WHO 1980 | WHO 2000/2004 | WHO 2010 | WHO 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islet cell tumor (adenoma/carcinoma) | Well-differentiated endocrine tumor/carcinoma (WDET/WDEC) | NET G1/G2 | NET G1/G2/G3 (well-differentiated NEN) |

| Poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma | Poorly differentiated encocrine carcinoma/small cell carcinoma (PDEC) | NEC (G3), large cell or small cell type | NEC (G3), large cell or small cell type (poorly differentiated NEN) |

| _ | Mixed exocrine-endocrine carcinoma (MEEC) | Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma | Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm |

| Pseudotumor lesions | Tumor-like lesions (TLLs) | Hyperplastic and preneoplastic lesions | _ |

Pathophysiology

Neuroendocrine system

- Endocrine system is a communication system & a network of glands that produce & secrete hormones in the bloodstream (usually) which act as biochemical messengers to regulate physiological events in living organisms & CNS performs the same function by using electrical impulses as messengers.

- Neuroendocrine system is actually a combination of above two systems, or the various interfaces between the two systems (more specifically) & a GEP-NET is a tumor of any such interface.

- Also includes cells that are not part of glands: the diffuse neuroendocrine system-scattered throughout other organs.

- A hormone is a chemical that delivers a particular message to a particular organ (typically remote from the hormone's origin), e.g., the hormone-insulin secreted by pancreas acts primarily to allow glucose to enter the body's cells to be used as fuel, the hormone-gastrin secreted by stomach tells the stomach to produce acids to digest food.

- Hormones can be divided into further subtypes such as peptides/peptide hormones, steroids, and neuroamines. In the context of GEP-NETs, the terms hormone and peptide are often used interchangeably.

- The vast majority of GEP-NETs fall into two nearly distinct categories: carcinoids, and pancreatic endocrine tumors (PETs).

- Despite great behavioral differences between the two, they are grouped together as GEP-NETs because of similarities in cell structure.[10]

- Pancreatic endocrine tumors (PETs) are also known as endocrine pancreatic tumors (EPTs) or islet cell tumors.

- PETs are assumed to originate generally in the islets of Langerhans within the pancreas – or, Arnold et alia suggest, from endocrine pancreatic precursor cells (Arnold et al. 2004, 199) – though they may originate outside of the pancreas. (The term pancreatic cancer almost always refers to adenopancreatic cancer, also known as exocrine pancreatic cancer. Adenopancreatic cancers are generally very aggressive, and are not a neuroendocrine cancers. About 95 percent of pancreatic tumors are adenopancreatic; about 1 or 2 percent are GEP-NETs).

- PETs may secrete hormones (as a result, perhaps, of impaired storage ability), and those hormones can wreak symptomatic havoc on the body.

- Those PETs that do not secrete hormones are called nonsecretory or nonfunctioning or nonfunctional tumors.

- Secretory tumors are classified by the hormone most strongly secreted – for example, insulinoma, which produces excessive insulin, and gastrinoma, which produces excessive gastrin (see more detail in the summary below).

- Carcinoid tumors are further classified, depending on the point of origin, as foregut (lung, thymus, stomach, and duodenum) or midgut (distal ileum and proximal colon) or hindgut (distal colon and rectum).

- Less than one percent of carcinoid tumors originate in the pancreas. But for many tumors, the point of origin is unknown.

- Carcinoid tumors, which secrete serotonin tend to grow much more slowly than PETs.

- Although this serotonin secretion is entirely different from a secretory PET's hormone secretion, carcinoid tumors with carcinoid syndrome are nevertheless sometimes called functioning, adding to the frequent confusion of carcinoids with PETs.

- Carcinoid syndrome is primarily associated with midgut carcinoids. A severe episode of carcinoid syndrome is called carcinoid crisis; it can be triggered by surgery or chemotherapy, among other factors. [11]

- The mildest of the carcinoids are discovered only upon surgery for unrelated causes. These coincidental carcinoids are common; one study found that one person in ten has them. [12]

- Neuroendocrine tumors other than coincidental carcinoids are rare.

- Incidence of PETs is estimated at one new case per 100,000 people per year; incidence of clinically significant carcinoids is twice that.

- Thus the total incidence of GEP-NETs in the United States would be about 9,000 new cases per year. But researchers differ widely in their estimates of incidence, especially at the level of the secretory subtypes (the various "-omas").

- In addition to the two main categories, there are even rarer forms of GEP-NETs. At least one form – neuroendocrine lung tumors – arises from the respiratory rather than the gastro-entero-pancreatic system.

- Non-human animals also suffer from GEP-NETs; for example, neuroendocrine cancer of the liver is a disease of dogs, and Devil facial tumor disease is a neuroendocrine tumor of Tasmanian Devils.

- Rufini et alia summarize: "Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms originating from endocrine cells, which are characterized by the presence of secretory granules as well as the ability to produce biogenic amines and polypeptide hormones.

- These tumors originate from endocrine glands such as the adrenal medulla, the pituitary, and the parathyroids, as well as endocrine islets within the thyroid or the pancreas, and dispersed endocrine cells in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract.

- The clinical behavior of NETs is extremely variable; they may be functioning or not functioning, ranging from very slow-growing tumors (well-differentiated NETs), which are the majority, to highly aggressive and very malignant tumors (poorly differentiated NETs).

- Classically, NETs of the gastrointestinal tract are classified into 2 main groups: (1) carcinoids and (2) endocrine pancreatic tumors (EPTs)" (Rufini, Calcagni, and Baum 2006). (Note that the definition of well-differentiated may be counterintuitive: a tumor is well-differentiated if its cells are similar to normal cells, which have a well-differentiated structure of nucleus, cytoplasm, membrane, etc).

- Ramage et alia provide a summary that differs somewhat from that of Rufini et alia: "NETs , originate from pancreatic islet cells, gastroenteric tissue (from diffuse neuroendocrine cells distributed throughout the gut), neuroendocrine cells within the respiratory epithelium, and parafollicullar cells distributed within the thyroid (the tumors being referred to as medullary carcinomas of the thyroid).

- Pituitary, parathyroid, and adrenomedullary neoplasms have certain common characteristics with these tumors but are considered separately" (Ramage et al. 2005, [14]).

Metastases and malignancy

- In the context of GEP-NETs, the terms metastatic and malignant are often used interchangeably.

- GEP-NETs are often malignant, since the primary site often eludes detection for years, sometimes decades – during which time the tumor has the opportunity to metastasize.

- Researchers differ widely in their estimates of malignancy rates, especially at the level of the secretory subtypes (the various "-omas").

- The most common metastatic sites are the liver, the lymph nodes, and the bones.

- Liver metastases are so frequent and so well-fed that for many patients, they dominate the course of the cancer.

- For a patient with a nonsecretory PET, for example, the primary threat to life may be the sheer bulk of the tumor load in the liver.

Causes

- In the normal pancreas, cells called islet cells produce hormones that regulate a variety of bodily functions, such as blood sugar level and the production of stomach acid.

- Islet cell tumors include:

- Various hereditary syndromes associated with GIT and pancreatobiliary tract NETs are mentioned in detail in the table below:

| Name of the syndrome | Pattern of inheritance | Chromosomal Band Location | Gene/ Protein Involved | GIT and Pancreatobiliary Tract NETs | Other Tumors of GIT and Pancreatobiliary Tract | Clinical Presentation Outside GIT and Pancreatobiliary Tract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN 1) |

|

|

|

Maybe associated with multiple:

|

|

More commonly:

Less commonly:

|

| von Hippel-Lindau disease/syndrome (VHL) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neurofibromatosis 1

(von Recklinghausen disease) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tuberous sclerosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other familial syndromes associated with neuroendocrine neoplasms are:

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 (MEN2)

- Carney complex

Epidemiology and Demographics

Lung NETs

- Lung neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) account for approximately 1 to 2 percent of all lung malignancies in adults and roughly 20 to 30 percent of all NETs

- Lung NETs are the most common primary lung neoplasm in children, typically presenting in late adolescence.[13][14][15][16]

- Globally, incidence rates range from 0.2 to 2 per 100,000 population per year, and most series suggest a higher incidence in women as compared with men and in whites as compared with blacks[17][18][19]

- In a nationwide registry-based Swedish series, the annual incidence rates of lung NETs among men and women were 0.2 and 1.3 per 100,000 population

- In data from the United States Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, the annual incidence of lung NETs between 2000 and 2012 was 1.49 per 100,000 population

- The average age of an adult diagnosed with a typical lung NET is 45 years, while in many series, individuals with atypical tumors are approximately 10 years older[20][21]

Digestive system NETs

- NENs of the digestive system arising in the tubular gastrointestinal tract and the pancreas are relatively rare. The annual incidence in the United States is approximately 3.56 per 100,000 population[19]

- Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are overall rare; they have an incidence of ≤1 case per 100,000 individuals per year and account for 1 to 2 percent of all pancreatic tumors

- Pancreatic NETs represent less than 3 percent of primary pancreatic neoplasms

- Approximately 80 to 100 percent of patients with MEN1, up to 20 percent of patients with VHL, 10 percent of patients with NF1, and 1 percent of patients with tuberous sclerosis will develop a pancreatic NET within their lifetime

Risk factors

- Smoking is a risk factor for both lung and pancreatic NETs especially in case of atypical tumors.[17][22][23]

- Inherited predisposition for lung NETs (not related to MEN syndrome)[24]

- Diabetes is associated with increased risk of pancreatic NETs

- Chronic pancreatitis is associated with increased risk of pancreatic NETs

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- Diabetes

- Hormone crises (if the tumor releases certain types of hormones)

- Severe low blood sugar (from insulinomas)

- Severe ulcers in the stomach and small intestine (from gastrinomas)

- Spread of the tumor to the liver

Prognosis

- You may be cured if the tumors are surgically removed before they have spread to other organs. If tumors are cancerous, chemotherapy may be used, but it usually cannot cure patients.

- Life-threatening problems (such as very low blood sugar) can occur due to excess hormone production, or if the cancer spreads throughout the body.

- In the largest series of poorly differentiated pancreatic NEC, 88 percent of the patients had lymph node or distant metastatic disease at presentation, and an additional 7 percent developed metastases subsequently. The median survival was 11 months (range 0 to 104 months), and the two- and five-year survival rates were 22.5 and 16.1 percent, respectively. [9]

History and Symptoms

- According to Arnold et alia, "many tumors are asymptomatic even in the presence of metastases" (Arnold et al. 2004, 197).

- A carcinoid tumor may produce serotonin (5-HT), a biogenic amine that causes a specific set of symptoms including:

- Flushing

- Diarrhea or increase in number of bowel movements

- Weight loss

- Weight gain

- Palpitations

- Congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Asthma

- Acromegaly

- Cushing's syndrome

- This set of symptoms is called Carcinoid syndrome.

- 50-85% of pancreatic NETs are nonfunctioning according to recent studies.

- Functioning pancreatic NETs present as:

- Insulinomas typically present with episodic hypoglycemia, which may cause confusion, visual change, unusual behavior, palpitations, diaphoresis, and tremulousness. Amnesia for hypoglycemia is common

- Gastrinomas typically present with peptic ulcer disease; diarrhea can also be a prominent feature

- The clinical syndrome classically associated with glucagonoma includes necrolytic migratory erythema, cheilitis, diabetes mellitus, anemia, weight loss, diarrhea, venous thrombosis, and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

- The main clinical features of VIPoma syndrome are watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hypochlorhydria.

Laboratory Findings

- Cells that receive hormonal messages do so through receptors on the surface of the cells. For reasons that are not understood, many neuroendocrine tumor cells possess especially strong receptors; for example, PETs often have strong receptors for somatostatin, a very common hormone in the body. We say that such tumor cells overexpress the somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) and are thus avid for the hormone; their uptake of the hormone is strong. This avidity for somatostatin is a key for diagnosis – and it makes the tumors vulnerable to certain targeted therapies.

- Aside from their use in diagnosis, some markers can track the progress of therapy while the patient avoids the detrimental side-effects of CT-scan contrast.

| List of potential markers for GEP-NETs apart from hormones of secretory tumors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Most important markers | Other markers | Newer (as of 2005) markers | |

|

|

|

|

CT Scan

- CT-scan is a common diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of Neuroendocrine tumors.

- CT-scans using contrast medium can detect 95 percent of tumors over 3 cm in size, and no tumors under 1 cm (University of Michigan Medical School n. d., [15]).

PET Scan

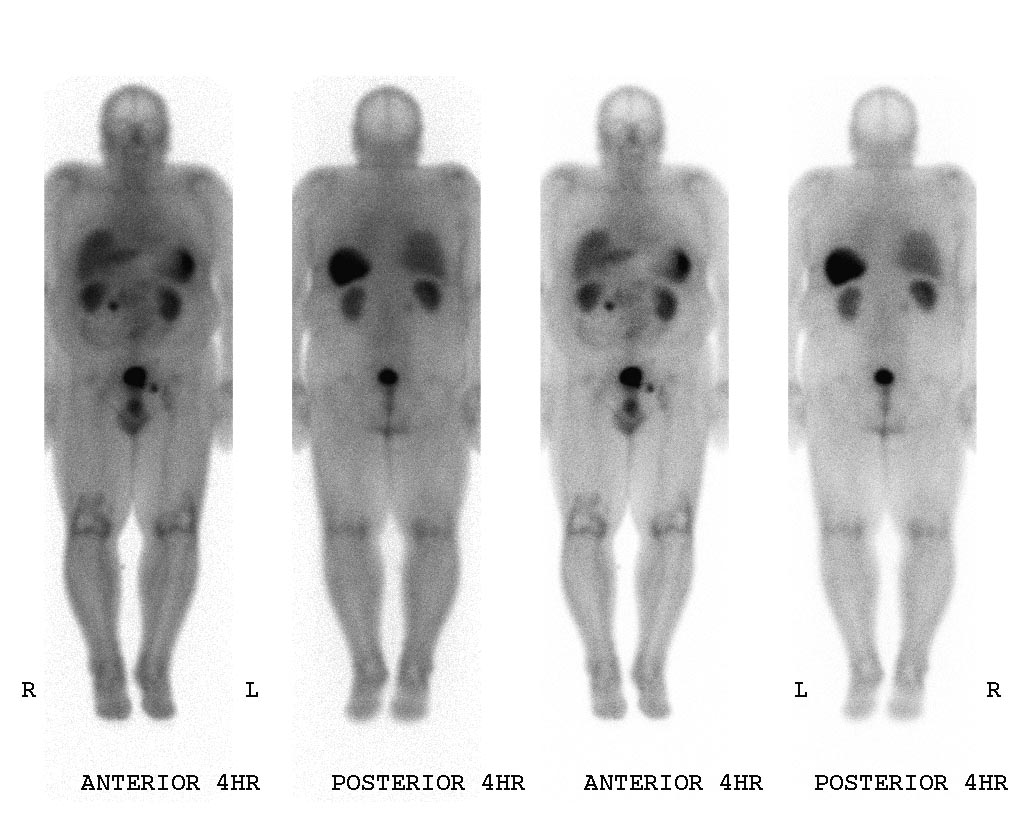

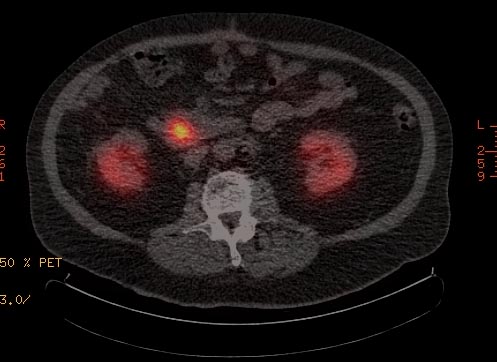

A gallium-68 receptor PET-CT, integrating a PET image with a CT image, is much more senstitive than an OctreoScan, and it generates objective (quantified) results in the form of a standardized uptake value (SUV).

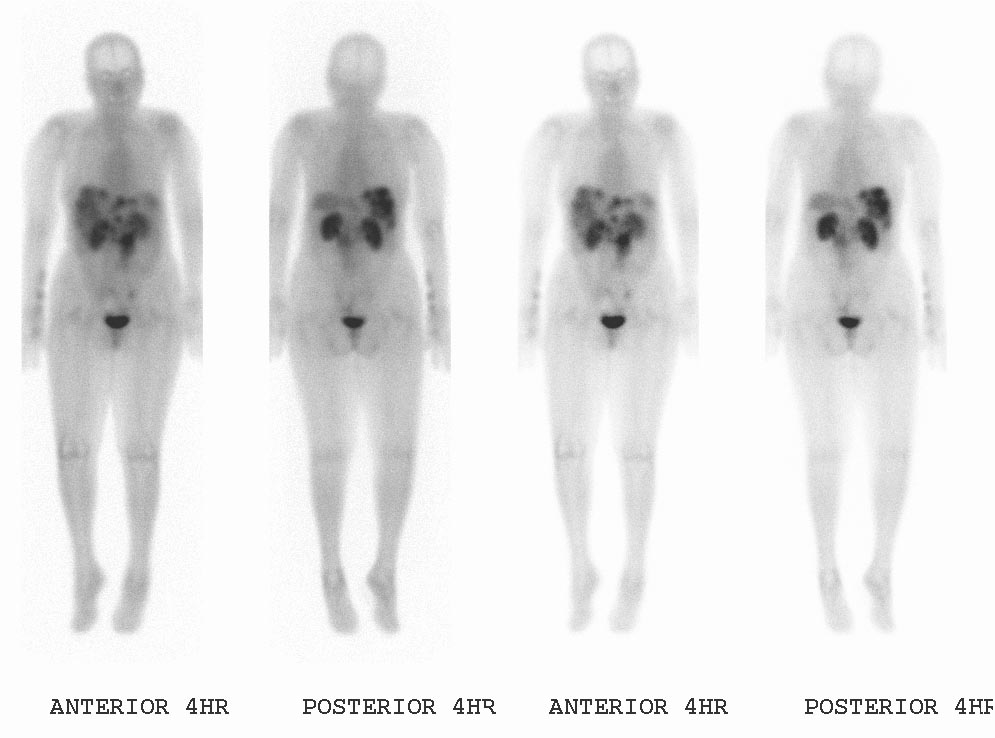

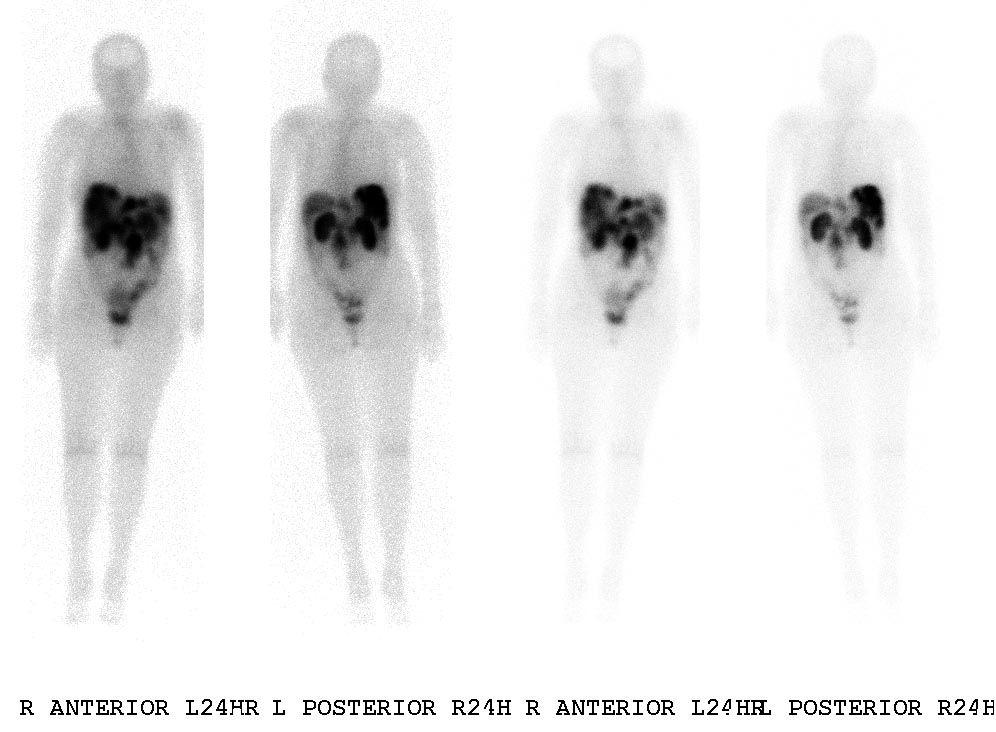

Octreoscan

The diagnostic procedure that utilizes a somatostatin analog is the OctreoScan, also called somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS or SSRS): a patient is injected with octreotide chemically bound to a radioactive substance, often indium-111; for those patients whose tumor cells are avid for octreotide, a radiation-sensitive scan can then indicate the locations of the larger lesions.

An OctreoScan is a relatively crude test that generates subjective results.

Medical Therapy

Approach

According to Warner, the best care, at least for noncarcinoid GEP-NETs, is provided by "an active [as opposed to wait-and-see] approach using sequential multimodality treatment" delivered by a "multidisciplinary team, which also may include a surgeon, endocrinologist, oncologist, interventional radiologist, and other specialists". This recommendation is based on his view that, except for most insulinomas, "almost all" PETs "have long-term malignant potential" – and in sixty percent of cases, that potential is already manifest. "Indeed, the most common cause of death from PETs is hepatic [that is, liver] failure" (Warner 2005, 4).

Two tricky issues in evaluating therapies are durability (is the therapy long-lasting?) and stasis (are the tumors neither growing nor shrinking?). For example, one therapy might give good initial results – but within months the benefit evaporates. And another therapy might be disparaged by some for causing very little tumor shrinkage, but be championed by others for causing significant tumoristasis.

The half-life of somatostatin in circulation is under three minutes, making it useless for diagnosis and targeted therapies. For this reason, The synthetic forms are typically called somatostatin analogs (somatostatin analogues), but according to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the proper term is somatostatin congeners. (In this article we conform to the old terminology, as the medical community has been slow to adopt the term congener.) The analogs have a much longer half-life than somatostatin, and other properties that make them more suitable for diagnosis and therapy.

Chemotherapy

The most common nonsurgical therapy for all GEP-NETs is chemotherapy, although chemotherapy is reported to be largely ineffective for carcinoids, not particularly durable (long-lasting) for PETs, and inappropriate for PETs of nonpancreatic origin. [25]

When chemotherapy fails, the most common therapy, in the United States, is more chemotherapy, with a different set of agents. Some studies have shown that the benefit from one agent is not highly predictive of the benefit from another agent, except that the long-term benefit of any agent is likely to be low.

Strong uptake of somatostatin analogs is a negative indication for chemo.

Symptomatic relief

There are two major somatostatin-analog-based targeted therapies. The first of the two therapies provides symptomatic relief for patients with secretory tumors. In effect, somatostatin given subcutaneously or intramuscularly "clogs up" the receptors, blocking the secretion of hormones from the tumor cells. Thus a patient who might otherwise die from severe diarrhea caused by a secretory tumor can gain additional years of life.

Specific counter-hormones or other hormone-blocking medications are sometimes also used to provide symptomatic relief.

Hormone-delivered radiotherapy – PRRT

The second of the two major somatostatin-analog-based targeted therapies is called peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), though we might simply call it hormone-delivered radiotherapy. In this form of radioisotope therapy (RIT), radioactive substances (called radionuclides or radioligands) are chemically conjugated with hormones (peptides or neuroamines); the combination is given intravenously to a patient who has good uptake of the chosen hormone. The radioactive labelled hormones enter the tumor cells, and the attached radiation damages the tumor- and nearby cells. Not all cells are immediately killed this way. The process of tumor cells dying as result of this therapy can go on for several months, even up to two years. In patients with strongly overexpressing tumor cells, nearly all the radiation either gets into the tumors or is excreted in urine. As Rufini et alia say, GEP-NETs "are characterized by the presence of neuroamine uptake mechanisms and/or peptide receptors at the cell membrane, and these features constitute the basis of the clinical use of specific radiolabeled ligands, both for imaging and therapy" (Rufini, Calcagni, and Baum 2006, [16]).

The use of PRRT for GEP-NETs is similar to the use of iodine-131 as a standard therapy (in use since 1943) for nonmedullary thyroid tumors (which are not GEP-NETs). Thyroid cells (whether normal or neoplastic) tend to be avid for iodine, and nearby cells are killed when iodine-131 is infused into the bloodstream and is soon attracted to thyroid cells. Similarly, overexpressing GEP-NET cells (neoplastic cells only) are avid for somatostatin analogs, and nearby cells are killed when radionuclides attached to somatostatin analogs are infused into the bloodstream and are soon attracted to the tumor cells. In both therapies, hormonal targeting delivers a much higher dose of radiation than external beam radiation could safely deliver.

As of 2006, PRRT is available in at least dozen medical centers in Europe. In the USA it is FDA-approved, and available at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, but using a radionuclide, indium-111, that is much weaker than the lutetium-177 and the even stronger yttrium-90 used on the European continent. In the UK, only the radionuclide metaiodobenzylguanidine (I-MIBG) is licensed (but GEP-NETs are rarely avid for MIBG). Most patients (from all over the world) are treated (with lutetium-177) in The Netherlands, at the Erasmus Medical Center. PRRT with lutetium or yttrium is nowhere an "approved" therapy, but the German health insurance system, for example, covers the cost for German citizens.

PRRT using yttrium or lutetium was first applied to humans about 1999. Practitioners continue to refine their choices of radionuclides to maximize damage to tumors, of somatostatin analogs to maximize delivery, of chelators to bind the radionuclides with the hormones (and chelators can also increase uptake), and of protective mechanisms to minimize damage to healthy tissues (especially the kidneys).

Hepatic artery-delivered therapies

- One therapy for liver metastases of GEP-NETs is hepatic artery embolization (HAE). Larry Kvols, of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida, says that "hepatic artery embolization has been quite successful. During that procedure a catheter is placed in the groin and then threaded up to the hepatic artery that supplies the tumors in the liver. We inject a material called embospheres [tiny spheres of glass or resin, also called microspheres] into the artery and it occludes the blood flow to the tumors, and in more than 80% of patients the tumors will show significant tumor shrinkage" (Kvols 2002, [17]). HAE is based on the observation that tumor cells get nearly all their nutrients from the hepatic artery, while the normal cells of the liver get about 75 percent of their nutrients (and about half of their oxygen) from the portal vein, and thus can survive with the hepatic artery effectively blocked.

- Another therapy is hepatic artery chemoinfusion, the injection of chemotherapy agents into the hepatic artery. Compared with systemic chemotherapy, a higher proportion of the chemotherapy agents are (in theory) delivered to the lesions in the liver.

- Hepatic artery chemoembolization (HACE), sometimes called transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), combines hepatic artery embolization with hepatic artery chemoinfusion: embospheres bound with chemotherapy agents, injected into the hepatic artery, lodge in downstream capillaries. The spheres not only block blood flow to the lesions, but by halting the chemotherapy agents in the neighborhood of the lesions, they provide a much better targeting leverage than chemoinfusion provides.

- Radioactive microsphere therapy (RMT) combines hepatic artery embolization with radiation therapy – microspheres bound with radionuclides, injected into the hepatic artery, lodge (as with HAE and HACE) in downstream capillaries. This therapy is also called selective internal radiation therapy, or SIRT. In contrast with PRRT, the lesions need not overexpress peptide receptors. (But PRRT can attack all lesions in the body, not just liver metastases.) Due to the mechanical targeting, the yttrium-labeled microspheres "are selectively taken up by the tumors, thus preserving normal liver" (Salem et al. 2002, [18]).

Other therapies

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is used when a patient has relatively few metastases. In RFA, a needle is inserted into the center of the lesion and is vibrated at high frequency to generate heat; the tumor cells are killed by cooking.

- Cryoablation is similar to RFA; an endothermic substance is injected into the tumors to kill by freezing. Cryoablation has been considerably less successful for GEP-NETs than RFA.

- Interferon is sometimes used to treat GEP-NETs; its use was pioneered by Dr. Kjell Öberg at Uppsala. For GEP-NETs, Interferon is often used at low doses and in combination with other agents (especially somatostatin analogs such as octreotide). But some researchers claim that Interferon provides little value aside from symptom control.

- As described above, somatostatin analogs have been used for about two decades to alleviate symptoms by blocking the production of hormones from secretory tumors. They are also integral to PRRT. In addition, some doctors claim that, even without radiolabeling, even patients with nonsecretory tumors can benefit from somatostatin analogs, which purportedly can shrink or stabilize GEP-NETs. But some researchers claim that this "cold" octreotide provides little value aside from symptom control.

Surgery

Surgery is the only therapy that can cure GEP-NETs. However, the typical delay in diagnosis, giving the tumor the opportunity to metastasize, makes most GEP-NETs ineligible for surgery (non-resectable).

Case Studies

External links

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D.

References

- ↑

"The APUD concept led to the belief that these cells arise from the embryologic neural crest. This hypothesis eventually was found to be incorrect" (Warner 2005, 2).

"The APUD-concept is currently abandoned" (Öberg 1998, 2, [1]).

- ↑ Inzani F, Petrone G, Rindi G (2018). "The New World Health Organization Classification for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasia". Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 47 (3): 463–470. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2018.04.008. PMID 30098710.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, Vestermark LW, Holt N, Osterlund P; et al. (2013). "Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the NORDIC NEC study". Ann Oncol. 24 (1): 152–60. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds276. PMID 22967994.

- ↑ Heetfeld M, Chougnet CN, Olsen IH, Rinke A, Borbath I, Crespo G; et al. (2015). "Characteristics and treatment of patients with G3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms". Endocr Relat Cancer. 22 (4): 657–64. doi:10.1530/ERC-15-0119. PMID 26113608.

- ↑ Basturk O, Yang Z, Tang LH, Hruban RH, Adsay V, McCall CM; et al. (2015). "The high-grade (WHO G3) pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor category is morphologically and biologically heterogenous and includes both well differentiated and poorly differentiated neoplasms". Am J Surg Pathol. 39 (5): 683–90. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000408. PMC 4398606. PMID 25723112.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tang LH, Untch BR, Reidy DL, O'Reilly E, Dhall D, Jih L; et al. (2016). "Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors with a Morphologically Apparent High-Grade Component: A Pathway Distinct from Poorly Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinomas". Clin Cancer Res. 22 (4): 1011–7. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0548. PMC 4988130. PMID 26482044.

- ↑ La Rosa S, Sessa F, Uccella S (2016). "Mixed Neuroendocrine-Nonneuroendocrine Neoplasms (MiNENs): Unifying the Concept of a Heterogeneous Group of Neoplasms". Endocr Pathol. 27 (4): 284–311. doi:10.1007/s12022-016-9432-9. PMID 27169712.

- ↑ Shia J, Tang LH, Weiser MR, Brenner B, Adsay NV, Stelow EB; et al. (2008). "Is nonsmall cell type high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the tubular gastrointestinal tract a distinct disease entity?". Am J Surg Pathol. 32 (5): 719–31. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e318159371c. PMID 18360283.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Basturk O, Tang L, Hruban RH, Adsay V, Yang Z, Krasinskas AM; et al. (2014). "Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 44 cases". Am J Surg Pathol. 38 (4): 437–47. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000169. PMC 3977000. PMID 24503751.

- ↑

"The main two groups of neuroendocrine GEP tumours are so-called carcinoid tumours and endocrine pancreatic tumours" (Öberg 2005a, 90, ).

"Less than 1% of carcinoids arise in the pancreas" (Warner 2005, 9).

Arnold et alia in effect define carcinoids as "extra-pancreatic endocrine gastronintestinal tumors" (Arnold et al. 2004, 196).

Some doctors believe that there is significant overlap between PETs and carcinoids. For example, endocrine surgeon Rodney Pommier says that "there are pancreatic carcinoids" (Pommier 2003, [2]). However, Pommier made his statement in a talk at a conference on carcinoids, not in a peer-reviewed journal; and in his talk he did not define the word carcinoid.

Another way to classify GEP-NETs is to separate those that begin in the glandular neuroendocrine system from those that begin in the diffuse neuroendocrine system. "Neuroendocrine tumors generally may be classified into two categories. The first category is an organ-specific group arising from neuroendocrine organs such as pituitary gland, thyroid, pancreas, and adrenal gland. The second group arises from the diffuse neuroendocrine cells/Kulchitsky cells that are widely distributed throughout the body and are highly concentrated in the pulmonary and gastrointestinal systems" (Liu et al. 2001, [3]).

- ↑ Larry Kvols, of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida, lists flushing, diarrhea, CHF, and asthma as the four critical characteristics of carcinoid syndrome (Kvols 2002, [4]).

- ↑

"[In] 800 autopsy cases, ... incidence of tumor was 10% (6/60) in individuals having histological studies of all sections of the pancreas" (Kimura, Kuroda, and Morioka 1991, [5]).

Small tumors are not necessarily harmless: Rodney Pommier tells of a "chick pea-sized tumor causing [so much] hormonal effect" that the patient was wheelchair-bound, unable to walk (Pommier 2003, [6]).

- ↑ Quaedvlieg PF, Visser O, Lamers CB, Janssen-Heijen ML, Taal BG (2001). "Epidemiology and survival in patients with carcinoid disease in The Netherlands. An epidemiological study with 2391 patients". Ann Oncol. 12 (9): 1295–300. doi:10.1023/a:1012272314550. PMID 11697843.

- ↑ Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M (2003). "A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors". Cancer. 97 (4): 934–59. doi:10.1002/cncr.11105. PMID 12569593.

- ↑ Hemminki K, Li X (2001). "Incidence trends and risk factors of carcinoid tumors: a nationwide epidemiologic study from Sweden". Cancer. 92 (8): 2204–10. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2204::aid-cncr1564>3.0.co;2-r. PMID 11596039.

- ↑ Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Waldum HL, Drozdov I, Chan AK; et al. (2008). "Neuroendocrine tumor epidemiology: contrasting Norway and North America". Cancer. 113 (10): 2655–64. doi:10.1002/cncr.23883. PMID 18853416.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Fink G, Krelbaum T, Yellin A, Bendayan D, Saute M, Glazer M; et al. (2001). "Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature". Chest. 119 (6): 1647–51. doi:10.1378/chest.119.6.1647. PMID 11399686.

- ↑ Gatta G, Ciccolallo L, Kunkler I, Capocaccia R, Berrino F, Coleman MP; et al. (2006). "Survival from rare cancer in adults: a population-based study". Lancet Oncol. 7 (2): 132–40. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70471-X. PMID 16455477.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y; et al. (2017). "Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States". JAMA Oncol. 3 (10): 1335–1342. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589. PMC 5824320. PMID 28448665.

- ↑ Skuladottir H, Hirsch FR, Hansen HH, Olsen JH (2002). "Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors: incidence and prognosis of histological subtypes. A population-based study in Denmark". Lung Cancer. 37 (2): 127–35. PMID 12140134.

- ↑ Cao C, Yan TD, Kennedy C, Hendel N, Bannon PG, McCaughan BC (2011). "Bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumors: long-term outcomes after resection". Ann Thorac Surg. 91 (2): 339–43. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.062. PMID 21256263.

- ↑ Froudarakis M, Fournel P, Burgard G, Bouros D, Boucheron S, Siafakas NM; et al. (1996). "Bronchial carcinoids. A review of 22 cases". Oncology. 53 (2): 153–8. doi:10.1159/000227552. PMID 8604242.

- ↑ Hassan MM, Phan A, Li D, Dagohoy CG, Leary C, Yao JC (2008). "Risk factors associated with neuroendocrine tumors: A U.S.-based case-control study". Int J Cancer. 123 (4): 867–73. doi:10.1002/ijc.23529. PMID 18491401.

- ↑ Oliveira AM, Tazelaar HD, Wentzlaff KA, Kosugi NS, Hai N, Benson A; et al. (2001). "Familial pulmonary carcinoid tumors". Cancer. 91 (11): 2104–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2104::aid-cncr1238>3.0.co;2-i. PMID 11391591.

- ↑

Ramage et alia say that "response to chemotherapy in patients with strongly positive carcinoid tumours was of the order of only 10% whereas patients with SSRS negative tumours had a response rate in excess of 70%. The highest response rates with chemotherapy are seen in the poorly differentiated and anaplastic NETs: response rates of 70% or more have been seen with cisplatin and etoposide based combinations. These responses may be relatively short lasting in the order of only 8–10 months. Response rates for pancreatic islet cell tumours vary between 40% and 70% and usually involve combinations of streptozotocin (or lomustine), dacarbazine, 5-fluorouracil, and adriamycin. However, the best results have been seen from the Mayo clinic where up to 70% response rates with remissions lasting several years have been seen by combining chemoembolisation of the hepatic artery with chemotherapy. The use of chemotherapy for midgut carcinoids has a much lower response rate, with 15–30% of patients deriving benefit, which may only last 6–8 months (Ramage et al. 2005, [7]).

For 125 patients with histologically proven unresectable islet-cell carcinomas, "median duration of regression was 18 months for the doxorubicin combination and 14 months for the 5-FU combination" (Arnold et al. 2004, 230).

- ↑

"The liver gets about 80% of its blood and half the oxygen from the portal vein, and only 20% of the blood and the other 50% of the oxygen from the artery.... The liver gets 80% of its blood from the portal vein and 20% from that little hepatic artery. But tumors get 100% of their blood off the hepatic artery, and this has been shown by multiple lines of evidence (Pommier 2003, [8]).

"The normal liver gets its blood supply from two sources; the portal vein (about 70%) and the hepatic artery (30%)" (Fong and Schoenfield n. d., [9]).

- ↑ "The theoretical advantage is that higher concentrations of the agents can be delivered to the tumors without subjecting the patients to the systemic toxicity of the agents.... In reality, however, much of the chemotherapeutic agents does end up in the rest of the body" (Fong and Schoenfield, [10]).

- ↑ The "microspheres preferentially cluster around the periphery of tumor nodules with a high tumor:normal tissue ratio of up to 200:1". The SIRT-spheres therapy is not FDA-approved for GEP-NETs; "it is FDA approved for liver metastases secondary to colorectal carcinoma and is under investigation for treatment of other liver malignancies, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroendocrine malignancies" (Welsh, Kennedy, and Thomadsen 2006, [11]).