Mepacrine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Atabrine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 80-90% |

| Elimination half-life | 5 to 14 days |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| E number | {{#property:P628}} |

| ECHA InfoCard | {{#property:P2566}}Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 36: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Chemical and physical data | |

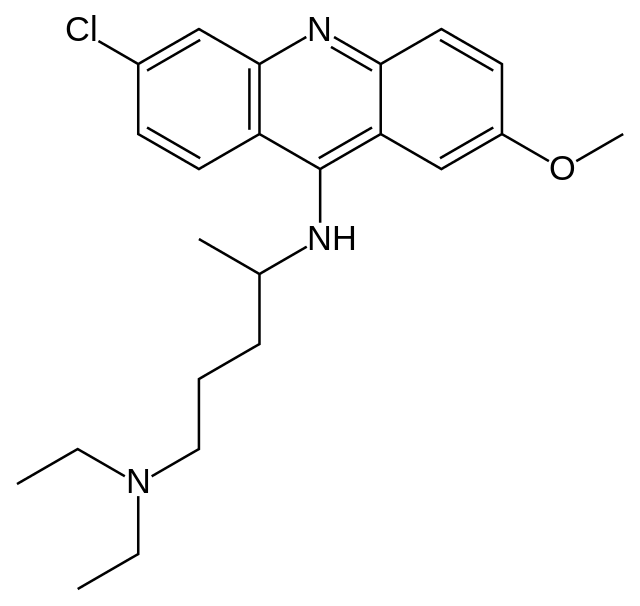

| Formula | C23H30ClN3O |

| Molar mass | 399.957 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Mepacrine |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Mepacrine |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Mepacrine at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Mepacrine at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Mepacrine

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Mepacrine Discussion groups on Mepacrine Directions to Hospitals Treating Mepacrine Risk calculators and risk factors for Mepacrine

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Mepacrine |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Mepacrine (INN; also called quinacrine in the United States and Atabrine (trade name) is a drug with several medical applications. It is related to mefloquine.

Medical uses

The main uses of mepacrine are as an antiprotozoal, antirheumatic and an intrapleural sclerosing agent.[1]

Antiprotozoal use include targeting giardiasis, where mepacrine is indicated as a primary agent for patients with metronidazole-resistant giardiasis and patients who should not receive or can not tolerate metronidazole. Giardiasis that is very resistant may even require a combination of mepacrine and metronidazole.[1]

Mepacrine is also used "off-label" for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus,[2] indicated in the treatment of discoid and subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, particularly in patients unable to take chloroquine derivatives.[1]

As an intrapleural sclerosing agent, it is used as pneumothorax prophylaxis in patients at high risk of recurrence, e.g., cystic fibrosis patients.[1]

Mepacrine is not the drug of choice because side effects are common, including toxic psychosis, and may cause permanent damage. See mefloquine for more information.

In addition to medical applications, mepacrine is an effective in vitro research tool for the epifluorescent visualization of cells, especially platelets. Mepacrine is a green fluorescent dye taken up by most cells. Platelets store mepacrine in dense granules.[3]

Mechanism

Its mechanism of action against protozoa is uncertain, but it is thought to act against the protozoan's cell membrane.

It is known to act as a histamine N-methyltransferase inhibitor.

It also inhibits NF-κB and activates p53.

History of uses

Antiprotozoal

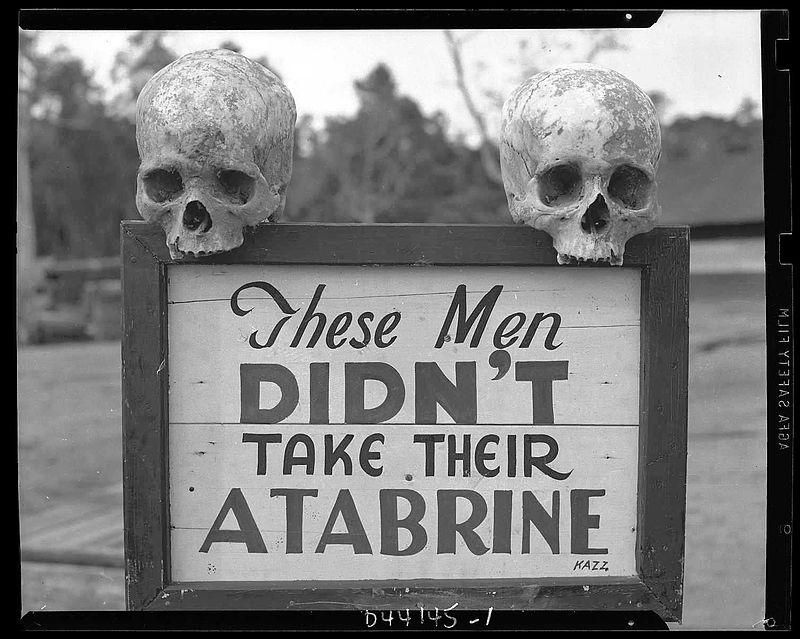

Mepacrine was initially approved in the 1930s as an antimalarial drug. It was used extensively during the second World War by US forces fighting in the Far East to prevent malaria.[4]

This antiprotozoal is also approved for the treatment of giardiasis (an intestinal parasite),[5] and has been researched as an inhibitor of phospholipase A2.

Scientists at Bayer in Germany first synthesised mepacrine in 1931. The product was one of the first synthetic substitutes for quinine although later superseded by chloroquine.

Anthelmintics

In addition it has been used for treating tapeworm infections.[6]

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Mepacrine has been shown to bind to the prion protein and prevent the formation of prion aggregates in vitro,[7] and full clinical trials of its use as a treatment for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease are under way in the United Kingdom and the United States. Small trials in Japan have reported improvement in the condition of patients with the disease,[8] although other reports have shown no significant effect,[9] and treatment of scrapie in mice and sheep has also shown no effect.[10][11] Possible reasons for the lack of an in-vivo effect include inefficient penetration of the blood brain barrier, as well as the existence of drug-resistant prion proteins that increase in number when selected for by treatment with mepacrine.[12]

Non-surgical sterilization for women

The use of mepacrine for non-surgical sterilization for women has also been studied. The first report of this method claimed a first year failure rate of 3.1%.[13] However, despite a multitude of clinical studies on the use of mepacrine and female sterilization, no randomized, controlled trials have been reported to date and there is some controversy over its use.[1]

Pellets of mepacrine are inserted through the cervix into a woman's uterine cavity using a preloaded inserter device, similar in manner to IUCD insertion. The procedure is undertaken twice, first in the proliferative phase, 6 to 12 days following the first day of the menstrual cycle and again one month later. The sclerosing effects of the drugs at the utero-tubal junctions (where the Fallopian tubes enter the uterus) results in scar tissue forming over a six week interval to close off the tubes permanently.

In the United States, this method has undergone Phase I clinical testing. The FDA has waived the necessity for Phase II clinical trials because of the extensive data pertaining to other uses of mepacrine. The next step in the FDA approval process in the United States is a Phase III large multi-center clinical trial. The method is currently used off-label.

Many peer reviewed studies suggest that[14] mepacrine sterilization (QS) is potentially safer than surgical sterilization.[15][16] Nevertheless, in 1998 the Supreme Court of India banned the import or use of the drug, allegedly based on reports that it could cause cancer or ectopic pregnancies.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Drugs.com: Quinacrine. Retrieved on August 24, 2009.

- ↑ Toubi E, Kessel A, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Paran D, Shoenfeld Y (2006). "The reduction of serum B-lymphocyte activating factor levels following quinacrine add-on therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus". Scand. J. Immunol. 63 (4): 299–303. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01737.x. PMID 16623930.

- ↑ Wall JE, Buijs-Wilts M, Arnold JT; et al. (1995). "A flow cytometric assay using mepacrine for study of uptake and release of platelet dense granule contents". Br J Haematol. 89 (2): 380&ndash, 385. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb03315.x.

- ↑ Baird JK (2011). "Resistance to chloroquine unhinges vivax malaria therapeutics". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 55 (5): 1827&ndash, 1830. doi:10.1128/aac.01296-10.

- ↑ Canete R, Escobedo AA, Gonzalez ME, Almirall P (2006). "Randomized clinical study of five days apostrophe therapy with mebendazole compared to quinacrine in the treatment of symptomatic giardiasis in children". World J. Gastroenterol. 12 (39): 6366–70. PMID 17072963.

- ↑ Template:DorlandsDict

- ↑ Doh-Ura K, Iwaki T, Caughey B (May 2000). "Lysosomotropic Agents and Cysteine Protease Inhibitors Inhibit Scrapie-Associated Prion Protein Accumulation". J Virol. 74 (10): 4894–7. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.10.4894-4897.2000. PMC 112015. PMID 10775631.

- ↑ Kobayashi Y, Hirata K, Tanaka H, Yamada T (July 2003). "[Quinacrine administration to a patient with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease who received a cadaveric dura mater graft--an EEG evaluation]". Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 43 (7): 403–8. PMID 14582366.

- ↑ Haïk S, Brandel J, Salomon D, Sazdovitch V, Delasnerie-Lauprêtre N, Laplanche J, Faucheux B, Soubrié C, Boher E, Belorgey C, Hauw J, Alpérovitch A (28 December 2004). "Compassionate use of quinacrine in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fails to show significant effects". Neurology. 63 (12): 2413–5. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000148596.15681.4d. PMID 15623716.

- ↑ Barret A, Tagliavini F, Forloni G, Bate C, Salmona M, Colombo L, De Luigi A, Limido L, Suardi S, Rossi G, Auvré F, Adjou K, Salès N, Williams A, Lasmézas C, Deslys J (August 2003). "Evaluation of Quinacrine Treatment for Prion Diseases". J Virol. 77 (15): 8462–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.15.8462-8469.2003. PMC 165262. PMID 12857915.

- ↑ Gayrard V, Picard-Hagen N, Viguié C, Laroute V, Andréoletti O, Toutain P (February 2005). "A possible pharmacological explanation for quinacrine failure to treat prion diseases: pharmacokinetic investigations in a ovine model of scrapie". Br J Pharmacol. 144 (3): 386–93. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706072. PMC 1576015. PMID 15655516. - Abstract

- ↑ Ghaemmaghami S, Ahn M, Lessard P, Giles K, Legname G; et al. (November 2009). Mabbott, Neil, ed. "Continuous Quinacrine Treatment Results in the Formation of Drug-Resistant Prions". PLoS Pathogens. 5 (11): 2413–5. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000673. PMC 2777304. PMID 19956709.

- ↑ Zipper J, Cole LP, Goldsmith A, Wheeler R, Rivera M. (1980). "Quinacrine hydrochloride pellets: preliminary data on a nonsurgical method of female sterilisation". Asia Oceania J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 18 (4): 275–90. PMID 6109672.

- ↑ International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (October 2003). "Quinacrine Sterilization: Reports on 40,252 cases". London: Elsevier. Vol 83 (Suppl. 2).

- ↑ Sokal, D.C., Kessel. E., Zipper. J., and King. T. (1994). "Quinacrine: Clinical experience". A background paper for the WHO consultation on the development of new technologies for female sterilization.

- ↑ Peterson, H.B., Lubell, L., DeStefano, F., and Ory, H.W. (1983). "The safety and efficacy of tubal sterilization: an international overview". Int J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 21 (2): 139–44. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(83)90051-6. PMID 6136433.

- ↑ George, Nirmala (July 25, 1998). "Govt drags feet on quinacrine threat". Indian Express..

External links

Template:Antiprotozoal agent Template:Excavata antiparasitics Template:Anthelmintics

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- Template:drugs.com link with non-standard subpage

- E number from Wikidata

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Articles without KEGG source

- Drugs with no legal status

- Antiprotozoal agents

- Antimalarial agents

- Sterilization

- Experimental methods of birth control

- Acridines

- Organochlorides

- Phenol ethers

- Aromatic amines