Influenza pathophysiology

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_me5EF0ne4&t=5s |350}} |

|

Influenza Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Influenza pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Influenza pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Influenza pathophysiology |

For more information about non-human (variant) influenza viruses that may be transmitted to humans, see Zoonotic influenza

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [3]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Alejandro Lemor, M.D. [4]

Overview

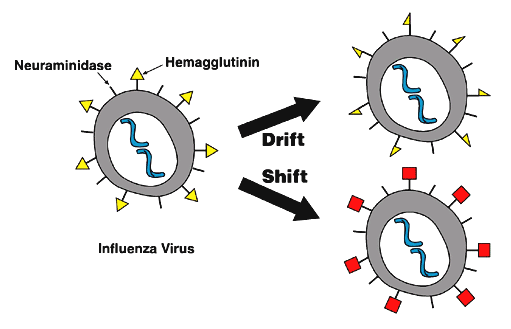

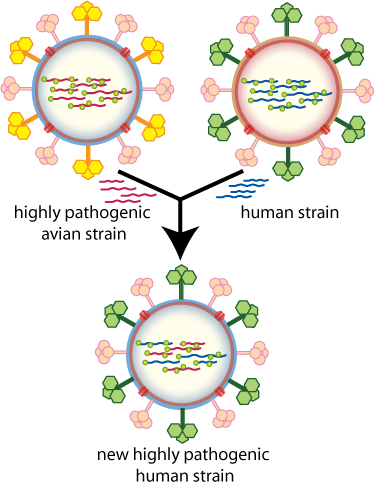

Influenza virus is under constant evolutionary change. These genetic changes may be small and chronic or large and abrupt. Small genetic changes happen continuously in Type A and Type B influenza as the virus makes copies of itself. This process is called antigenic drift. Drifting happens frequently enough to make new strains of virus unrecognizable to the human immune system. Type A influenza also undergoes infrequent and sudden changes known as antigenic shift. Antigenic shift occurs when two different flu strains infect the same cell and combine portions of their genetic material. The novel assortment of HA and/or NA proteins in a shifted virus may create a new influenza A subtype. Influenza viruses spread mainly through tiny droplets expelled when people with the disease cough, sneeze, or talk.

Pathophysiology

- Most healthy adults may be able to infect other people beginning 1 day before symptoms develop and up to 5 to 7 days after becoming sick.

- Children may pass the virus for longer than 7 days.

- Symptoms start 1 to 4 days after the virus enters the body, that means that infected patients are able to pass transmit the disease to someone else before knowing they are sick.

- Some people can be infected with the flu virus but have no symptoms. During this time, those persons may still spread the virus to others.

- Influenza viruses are constantly changing. They can change in two different ways, the antigenic drift and the antigenic shift.

|

|

Antigenic Drift[1]

- These are small changes in the genes of influenza viruses that happen continually over time as the virus replicates.

- These small genetic changes usually produce viruses that are pretty closely related to one another, which can be illustrated by their location close together on a phylogenetic tree.

- Viruses that are closely related to each other usually share the same antigenic properties and an immune system exposed to an similar virus will usually recognize it and respond. (This is sometimes called cross-protection.)

- But these small genetic changes can accumulate over time and result in viruses that are antigenically different (further away on the phylogenetic tree).

- When this happens, the body’s immune system may not recognize those viruses.

- This process works as follows:

- A person infected with a particular flu virus develops antibody against that virus.

- As antigenic changes accumulate, the antibodies created against the older viruses no longer recognize the “newer” virus, and the person can get sick again.

- Genetic changes that result in a virus with different antigenic properties is the main reason why people can get the flu more than one time.

- This is also why the flu vaccine composition must be reviewed each year, and updated as needed to keep up with evolving viruses.

Antigenic Shift

Adapted from CDC [1]

- Antigenic shift is an abrupt, major change in the influenza A viruses, resulting in new hemagglutinin and/or new hemagglutinin and neuraminidaseproteins in influenza viruses that infect humans.

- Shift results in a n ew influenza A subtype or a virus with a hemagglutinin or a hemagglutinin and neuraminidase combination that has emerged from an animal population that is so different from the same subtype in humans that most people do not have immunity to the new (e.g. novel) virus.

- Such a “shift” occurred in the spring of 2009, when an H1N1 virus with a new combination of genes emerged to infect people and quickly spread, causing a pandemic.

- When shift happens, most people have little or no protection against the new virus.

- While influenza viruses are changing by antigenic drift all the time, antigenic shift happens only occasionally.

- Influenza type A viruses undergo both kinds of changes

- Influenza type B viruses change only by the more gradual process of antigenic drift.

-

Antigenic Drift

Click on the image to expand.

Image courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [1] -

Antigenic Shift

Click on the image to expand.

Image courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [2]

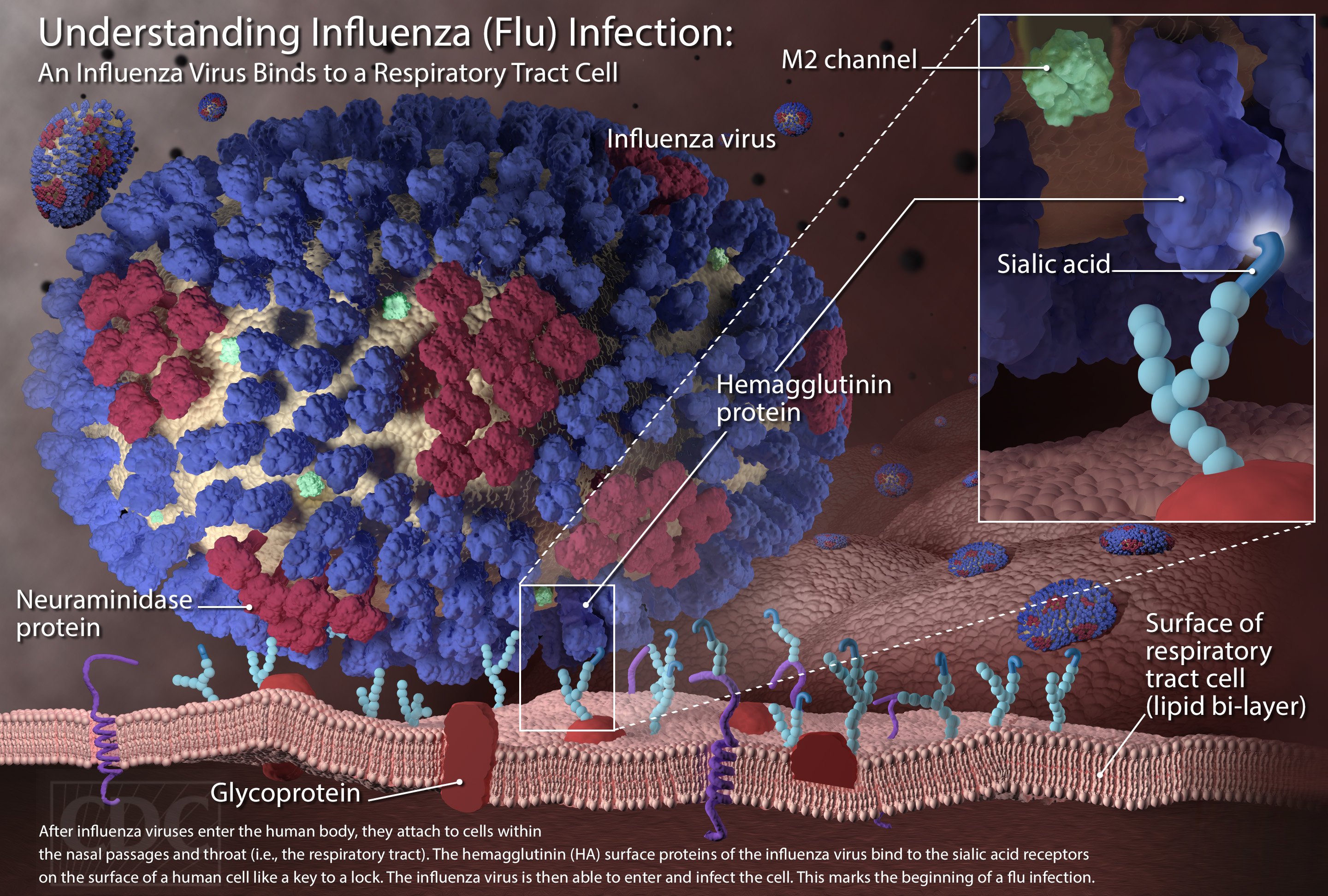

Cellular Pathogenesis

|

Transmission

Person-to-person Transmission Adapted from CDC [2]

- People with influenza infection can spread the disease to others up to about 6 feet away.

- Most experts think that influenza viruses are spread mainly by droplets made when people with flu cough, sneeze or talk.

- These droplets can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby or possibly be inhaled into the lungs.

- Less often, a person might also get flu by touching a surface or object that has flu virus on it and then touching their own mouth or nose.

- To avoid this, people should stay away from sick people and stay home if sick.

- It also is important to wash hands often with soap and water.

- If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub.

- Linens, eating utensils, and dishes belonging to those who are sick should not be shared without washing thoroughly first.

- Eating utensils can be washed either in a dishwasher or by hand with water and soap and do not need to be cleaned separately. Further, frequently touched surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected at home, work and school, especially if someone is ill.

Animal-to-person Transmission Adapted from CDC [3]

| Species | Hemagglutinin Subtypes |

Neuraminidase Subtypes |

|---|---|---|

| Humans | H1, H2, H3, H5, H6, H7, H9, H10 | N1, N2, N6, N7, N8, N9 |

| Poultry | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, H8, H9, H10, H11, H12, H13, H14, H15, H16 | N1, N2, N3, N4, N5, N6, N7, N8, N9 |

| Pigs | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H9 | N1, N2 |

| Bats | H17, H18 | N10, N11 |

| Adapted from CDC [3] | ||

- Influenza A viruses are found in many different animals, including ducks, chickens, pigs, whales, horses and seals.

- Influenza B viruses circulate widely only among humans.

- Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two proteins on the surface of the virus: the hemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N).

- There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes. All known subtypes of influenza A viruses have been found among birds, except subtype H17N10 and H18N11 which have only been found in bats.

- Wild birds are the primary natural reservoir for all subtypes of influenza A viruses and are thought to be the source of influenza A viruses in all other animals.

- Most influenza viruses cause asymptomatic or mild infection in birds; however, the range of symptoms in birds varies greatly depending on the properties of the virus.

- Infection with certain avian influenza A viruses (for example, some H5 and H7 viruses) can cause widespread, severe disease and death among some species of wild and especially domestic birds such as chickens and turkeys.

- Pigs can be infected with both human and avian influenza viruses in addition to swine influenza viruses.

- Infected pigs get symptoms similar to humans, such as cough, fever and runny nose. Because pigs are susceptible to avian, human and swine influenza viruses, they potentially may be infected with influenza viruses from different species (e.g., ducks and humans) at the same time. If this happens, it is possible for the genes of these viruses to mix and create a new virus.

- If a pig were infected with a human influenza virus and an avian influenza virus at the same time, the viruses could mix (reassort) and produce a new virus that had most of the genes from the human virus, but a hemagglutinin and/or neuraminidase from the avian virus.

- The resulting new virus would likely be able to infect humans and spread from person to person, but it would have surface proteins (hemagglutinin and/or neuraminidase) not previously seen in influenza viruses that infect humans.

- While it is unusual for people to get influenza infections directly from animals, sporadic human infections and outbreaks caused by certain avian influenza A viruses have been reported.

Asthmatic Patients

- Patients with asthma are not more likely to get influenza but the disease can be more serious for them.

- Even if their asthma is mild or their symptoms are well-controlled by medication.

- This is because patients with asthma have swollen and sensitive airways, and influenza can cause further inflammation of the airways and lungs.

- Influenza infection in the lungs can trigger asthma attacks and a worsening of asthma symptoms.

- Adults and children with asthma are more likely to develop pneumonia after getting sick with the flu than people who do not have asthma.

![Antigenic Drift Click on the image to expand. Image courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [1]](/images/0/0d/Antigenic_Drift_Influenza.jpg)

![Antigenic Shift Click on the image to expand. Image courtesy of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [2]](/images/6/6c/Antigenic_Shift_Influenza.jpg)