Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Overview

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | |

| |

|---|---|

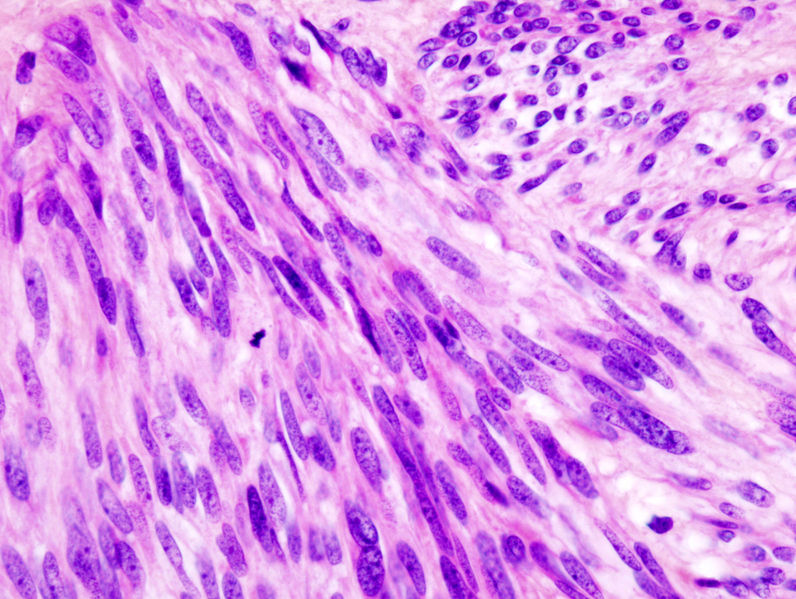

| Histopathologic image of gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the stomach. Hematoxylin-eosin stain. | |

| DiseasesDB | 33849 |

| MeSH | D046152 |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

In medical oncology, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are a rare tumor of the gastrointestinal tract (1-3% of all gastrointestinal malignancies).

GIST is a form of connective tissue cancer, or sarcoma. GISTs are therefore non-epithelial tumors, separate from more common forms of bowel cancer. 70% occur in the stomach, 20% in the small intestine and less than 10% in the esophagus. Small tumors are generally benign, especially when cell division rate is slow, but large tumors disseminate to the liver, omentum and peritoneal cavity. They rarely occur in other abdominal organs.

Signs and symptoms

Patients present with trouble swallowing, gastrointestinal hemorrhage or metastases (mainly in the liver). Intestinal obstruction is rare, due to the tumor's outward pattern of growth. Often, there is a history of vague abdominal pain or discomfort, and the tumor has become rather large by time the diagnosis is made.

Generally, the definitive diagnosis is made with a biopsy, which can be obtained endoscopically, percutaneously with CT or ultrasound guidance or at the time of surgery.

Diagnosis

As part of the analysis, blood tests and CT scanning are often undertaken (see the radiology section).

A biopsy sample will be investigated under the microscope. The histopathologist identifies the characteristics of GISTs (spindle cells in 70-80%, epitheloid aspect in 20-30%). Smaller tumors can usually be found to the muscularis propria layer of the intestinal wall. Large ones grow, mainly outward, from the bowel wall until the point where they outstrip their blood supply and necrose (die) on the inside, forming a cavity that may eventually come to communicate with the bowel lumen.

When GIST is suspected—as opposed to other causes for similar tumors—the histopathologist can use immunohistochemistry (specific antibodies that stain the molecule CD117 (also known as c-kit) —see below). 95% of all GISTs are CD117-positive (other possible markers include CD34, desmin, vimentin and others). Other cells that show CD117 positivity are mast cells.

Some tumors of the stomach and small bowel referred to as leiomyosarcomas (malignant tumor of smooth muscle) would most likely be reclassified as GISTs today on the basis of immunohistochemical staining.

Radiology

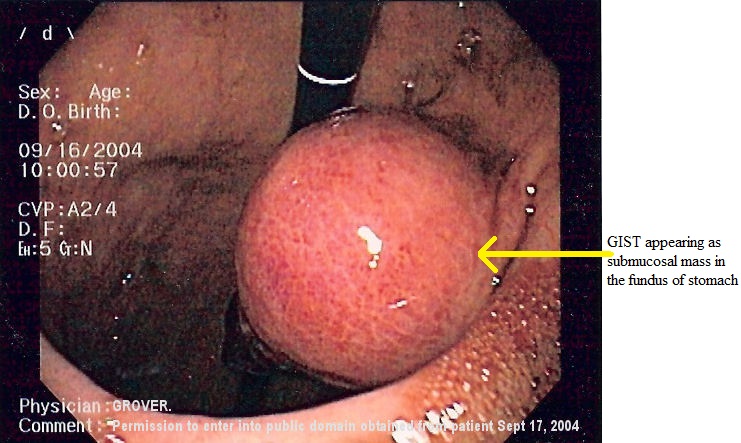

Barium fluoroscopic examinations (upper GI series and small bowel series (small bowel follow-through)) and CT are commonly used to evaluate the patient with upper abdominal pain. Both are adequate to make the diagnosis of GIST, although small tumors may be missed, especially in cases of a suboptimal examination.

Small GISTs appear as intramural masses. When large (> 5 cm), they most commonly grow outward from the bowel. Internal calcifications may be present. As the tumor outstrips its blood supply, it can necrose internally, creating a central fluid-filled cavity that can eventually ulcerate into the lumen of the bowel or stomach.

The tumor can directly invade adjacent structures in the abdomen. The most common site of spread is to the liver. Spread to the peritoneum may be seen. In distinction to gastric adenocarcinoma or gastric/small bowel lymphoma, malignant adenopathy (swollen lymph nodes) is uncommon (<10%).

Pathophysiology

GISTs are thought to arise from interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC),[1] that are normally part of the autonomic nervous system of the intestine. They serve a pacemaker function in controlling motility.

Most (50-80%) GISTs arise because of a mutation in a gene called c-kit. This gene encodes a transmembrane receptor for a growth factor termed scf (stem cell factor). The c-kit/CD117 receptor is expressed on ICCs and a large number of other cells, mainly bone marrow cells, mast cells, melanocytes and several others. In the gut, however, a mass staining positive for CD117 is likely to be a GIST, arising from ICC cells.

The c-kit molecule comprises a long extracellular domain, a transmembrane segment, and an intracellular part. Mutations generally occur in the DNA encoding the intracellular part (exon 11), which acts as a tyrosine kinase to activate other enzymes. Mutations make c-kit function independent of activation by scf, leading to a high cell division rate and possibly genomic instability. It is likely that additional mutations are "required" for a cell with a c-kit mutation to develop into a GIST, but the c-kit mutation is probably the first step of this process.

The tyrosine kinase function of c-kit is vital in the therapy for GISTs, please see below.

Genetics

Although some families with hereditary GISTs have been described, most cases are sporadic.

In GIST cells, the c-kit gene is mutated approximately 85% to 90% of the time. 35% of the GIST cells that do not have a mutated c-kit ("wild-type") do have a mutation in another gene, PDGFR-α (platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha), which is a related tyrosine kinase. Mutations in the exons 11, 9 and rarely 13 and 17 of the c-kit gene are known to occur in GIST. D816V point mutations in c-kit exon 17 are responsible for resistance to targeted therapy drugs like imatinib mesylate. Mutations in c-kit and PDGFrA are mutually exclusive[3][4].

Epidemiology

GISTs occur in 10-20 per one million people; one out of 3-4 is malignant. The true incidence might be higher, as novel laboratory methods are much more sensitive in diagosing GISTs. In all, there are approximately 3000-3500 cases of GIST per year in the United States. This makes GIST the most common form of sarcoma, which constitutes more than 70 types of cancer, but in all forms constitutes less than 1% of all cancer.

Therapy

Most small GISTs (<5 and especially <2 cm) with a low rate of mitosis (<5 dividing cells per 50 high-power fields) are benign and—after surgery—do not require adjuvant therapy.

Larger GISTs (>5 cm), and especially when the cell division rate is high (>6 mitoses/50 HPF), may disseminate and/or recur.

Until recently, GISTs were notorious for being resistant to chemotherapy, with a success rate of <5%. Recently, the c-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Glivec®/Gleevec®), a drug initially marketed for chronic myelogenous leukemia, was found to be useful in treating GISTs, leading to a 40-70% response rate in metastatic or inoperable cases.

Patients who become refractory on imatinib may respond to the multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib (marketed as Sutent).

Therapy for GIST is best directed by physicians familiar with the disease. Such doctors, specifically surgeons and medical oncologists, are found at major cancer centers.

History

Until the 1990s, all non-epithelial tumors of the gastrointestinal tract were called "gastrointestinal stromal tumors" from smooth muscle origin. Histopathologists generally did not distinguish between the types, as this did affect neither therapy nor prognosis. Subsequently, CD34, and later CD117 were identified as markers that could distinguish the various types.

Sources

- De Silva MV, Reid R. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): c-kit mutations, CD117 expression, differential diagnosis and targeted cancer therapy with imatinib. Pathol Oncol Res 2003;9:13-9. PMID 12704441.

- Kitamura Y, Hirota S, Nishida T. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a model for molecule-based diagnosis and treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Sci 2003:94:315-20. PMID 12824897.

References

- ↑ Miettinen M, Lasota J (2006). "Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis". Arch Pathol Lab Med. 130 (10): 1466–78. PMID 17090188.

External links

Research Links

- American Society of Clinical Oncology "Other Gastrointestinal Cancer" Abstracts (2005)

Patient-Oriented Websites

- GIST Support International, An international organization for the support of GIST patients, families, and friends. Includes detailed information from some of the foremost experts on GIST, links to research, treatment options, GIST registry.

- Life Raft Group International GIST Advocacy Organization. Provides support to patients & families, through information, education, and innovative research.

- GIST Info Patient links, includes information on new clinical trials and research

- American Cancer Society Patient Guide to GIST tumors.

Online Support Groups

- ACOR STI571-GIST support group, started in Dec 2000 by the Life Raft Group

- GIST Support International listserv support and information, started in March 2003 and associated wiki.

- Pediatric and Carney Triad listserv support and information for all families facing pediatric GIST or Carney Triad, started in Jan 2007.

de:Gastrointestinaler Stromatumor it:Tumore stromale gastrointestinale