Gabapentin detailed information

| File:Gabapentin.svg | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Rapid, in part by saturable carrier-mediated L-amino acid transport system 60% for 0.9 g daily to 27% for 4.8 g daily dose Food increases absorption by 14% |

| Protein binding | Less than 3% |

| Metabolism | Not appreciably metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | 5 to 7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| E number | {{#property:P628}} |

| ECHA InfoCard | {{#property:P2566}}Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 36: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Chemical and physical data | |

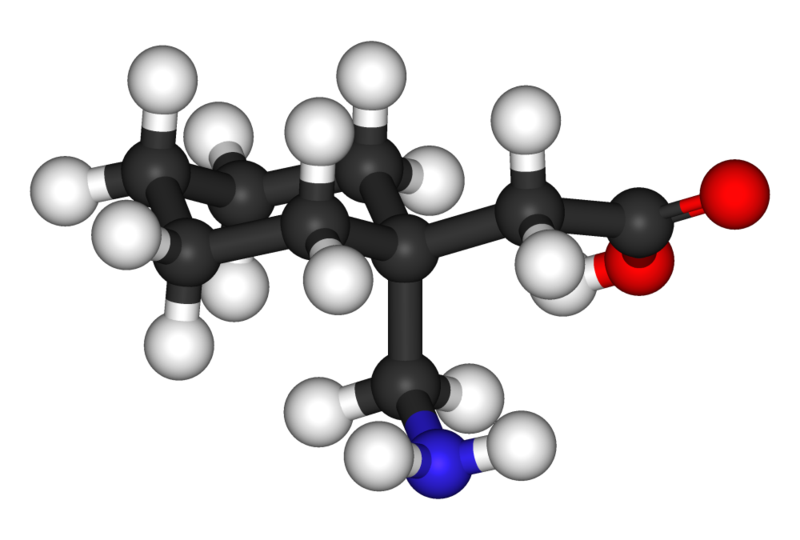

| Formula | C9H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 171.237 g/mol |

Gabapentin (brand name Neurontin) is a medication originally developed for the treatment of epilepsy. Presently, gabapentin is widely used to relieve pain, especially neuropathic pain. Gabapentin is well tolerated in most patients, has a relatively mild side-effect profile, and passes through the body unmetabolized.

Gabapentin was initially synthesized to mimic the chemical structure of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), but is not believed to act on the same brain receptors. Its exact mechanism of action is unknown, but its therapeutic action on neuropathic pain is thought to involve voltage-gated N-type calcium ion channels. It is thought to bind to the α2δ subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel in the central nervous system.

Clinical uses

Gabapentin was originally approved in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1994 for use as an adjunctive medication to control partial seizures (effective when added to other antiseizure drugs). In 2002, approval was added for treating postherpetic neuralgia (neuropathic pain following shingles, other painful neuropathies, and nerve related pain).[2]

Although not "indicated" (i.e., not FDA-approved), gabapentin has been found to be effective in prevention of frequent migraine headaches,[3] neuropathic pain[4] and nystagmus.[5]

Gabapentin has also been used in the treatment of bipolar disorder. However, its off-label use for this purpose is increasingly controversial.[6] Some claim gabapentin acts as a mood stabilizer and has the advantage of having fewer side-effects than more conventional bipolar drugs such as lithium and valproic acid. Some small, non-controlled studies in the 1990s, most sponsored by gabapentin's manufacturer, suggested that gabapentin treatment for bipolar disorder may be promising.[6] However, more recently, several larger, controlled, and double-blind studies have found that gabapentin was no more effective than (and in one study, slightly less effective than) placebo.[7] Despite this scientific evidence that gabapentin in the treatment of bipolar disorder is not an optimal treatment, many psychiatrists continue to prescribe it for this purpose.

Gabapentin has limited usefulness in the treatment of anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, in treatment-resistant depression, and for insomnia.[8][9] Gabapentin may be effective in reducing pain and spasticity in multiple sclerosis.[6]

Gabapentin has also been found to help patients with post-operative chronic pain (usually caused by nerves that have been severed accidentally in an operation and when grown back, have reconnected incorrectly). Symptoms of this include a tingling sensation near or around the area where the operation was performed, sharp shooting pains, severe aches after much movement, constant 'low ache' all day and sometimes a general 'weak' feeling. These symptoms can appear many months after an operation, and therefore the condition can go unnoticed.

Gabapentin is also prescribed to patients being treated with anti-androgenic compounds to reduce the incidence and intensity of the accompanying hot flushes.[10]

Gabapentin (administered orally) is one of two medications (the other being flumazenil, which is administered intravenously) used in the expensive Prometa Treatment Protocol for methamphetamine, cocaine and alcohol addiction. Gabapentin is administered at a dosage of 1200 mg taken at bedtime for 40–60 days. Though the combination of flumazenil infusions and gabapentin tablets is a licensed treatment, there is no prohibition against a physician prescribing gabapentin outside the Prometa protocol. There have been reports by methamphetamine addicts that gabapentin alone in doses of 1200 mg at bedtime taken for 40–60 days has been effective in reducing the withdrawal symptoms and almost eliminating cravings or desire to use methamphetamine.[citation needed]

Gabapentin has occasionally been prescribed for treatment of idiopathic subjective tinnitus, but a double blind, randomized controlled trial found it ineffective.[11]

Marketing of gabapentin

Gabapentin is best known under the brand name Neurontin manufactured by Pfizer subsidiary Parke-Davis. A Pfizer subsidiary named Greenstone markets generic Gabapentin.

In December 2004, the FDA granted final approval to a generic equivalent to Neurontin made by Israeli firm Teva.

Neurontin is one of Pfizer’s best selling drugs, and was one of the 50 most prescribed drugs in the United States in 2003. However, in recent years Pfizer has come under heavy criticism for its marketing of Neurontin, facing allegations that behind the scenes Parke-Davis marketed the drug for at least a dozen supposed uses for which the drug had not been FDA approved.

By some estimates, so-called off-label prescriptions account for roughly 90% of Neurontin sales.[12] While off-label prescriptions are common for a number of drugs and are perfectly legal (if not always appropriate), marketing of off-label uses of a drug is strictly illegal.[13] In 2004, Warner-Lambert agreed to plead guilty and pay $430 million in fines to settle civil and criminal charges regarding the illegal marketing of Neurontin for off-label purposes, and further legal action is pending. The courts of New York State, for example, have refused to certify a class of injured parties who took Neurontin for off-label use, finding that they had failed to state that they had had any injury.[14]

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) has archived [15] and studied [16] the documents made public by this case which opens a unique window into pharmaceutical marketing and illegal drug promotion. However, Pfizer maintains that the illegal activity originated in 1996, well before it accquired Parke-Davis (through its acquisition of Warner-Lambert) in 2000. Several lawsuits are underway after people prescribed gabapentin for off-label treatment of bipolar disorder attempted or committed suicide.

Pfizer has developed a successor to gabapentin, called pregabalin (being marketed as Lyrica). Structurally related to gabapentin, pregabalin is effective for neuropathic pain associated with diabetes, fibromyalgia, and shingles, as well as for the treatment of epilepsy and seizures.

Side effects

Gabapentin's most common side effects in adult patients include dizziness, drowsiness, and peripheral edema (swelling of extremities)[17]; these mainly occur at higher doses, in the elderly. Children 3–12 years of age were also observed to be susceptible to mild-to-moderate mood swings, hostility, concentration problems, and hyperactivity. An increase in formation of adenocarcinomas was observed in rats during preclinical trials, however the clinical significance of these results remains undetermined. Although rare, there are several cases of hepatotoxicity reported in the literature.[18] Gabapentin should be used carefully in patients with renal impairment due to possible accumulation and toxicity.[19][20] Gabapentin has an iGuard risk rating of Orange[21] (elevated risk).

Abuse potential

Though gabapentin is not a controlled substance, it does produce psychoactive effects that could lead to abuse of the drug. However, it is widely regarded as having little or no abuse potential. Pregabalin, a gabapentinoid with higher potency marketed for neuropathic pain, is a controlled substance, under the DEA Schedule V.

References

- ↑ BNF (March 2003) 45

- ↑ Pfizer: Product Monograph Template:PDF Retrieved 14 August 2006

- ↑ Mathew, NT (2001). "Efficacy of gabapentin in migraine prophylaxis". Headache. 41 (2): 119–28. ISSN 0017-8748. PMID 11251695. Retrieved 2006-08-14. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Backonja, MM (2004). "Pharmacologic management part 1: better-studied neuropathic pain diseases". Pain Med. 5 (Suppl 1): S28–47. ISSN 1526-2375. PMID 14996228. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Choudhuri, I (May 26, 2006). "Survey of management of acquired nystagmus in the United Kingdom". Eye. ISSN 0950-222X. PMID 16732211. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mack, Alicia (2003). "Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin" (PDF). Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 9 (6): 559–68. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

- ↑ Pande, AC (2000). "Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy". Bipolar Disorders (Abstract)

|format=requires|url=(help). 2 (3 Pt 2): 249–55. PMID 11249802. Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Chouinard, G (2006). "The search for new off-label indications for antidepressant, antianxiety, antipsychotic and anticonvulsant drugs". J Psychiatry Neurosci. 31 (3): 168–176. ISSN 1180-4882. PMID 16699602. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Frye, Mark A. (2000). "A Placebo-Controlled Study of Lamotrigine and Gabapentin Monotherapy in Refractory Mood Disorders" (Abstract). Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 20 (6): 607–14. Retrieved 2006-08-14. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Guttuso, T Jr (2003). "Gabapentin's effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial". Obstet Gynecol. 101 (2): 337–45. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Piccirillo, JF (2007). "Relief of idiopathic subjective tinnitus: is gabapentin effective?". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 133 (4): 390–7. PMID 17438255. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Huge penalty in drug fraud, Pfizer settles felony case in Neurontin off-label promotion". San Francisco Chronicle. 2004-05-14. p. C-1. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Jane E. Henney, MD (2006). "Editorial: Safeguarding Patient Welfare: Who's In Charge?". Annals of Internal Medicine. 145 (4): 305–307. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

- ↑ http://www.courts.state.ny.us/reporter/3dseries/2007/2007_05813.htm Baron v. Pfizer, Inc., 2007 N.Y. Slip Op. 05813 (App. N.Y., July 5, 2007)]

- ↑ http://dida.library.ucsf.edu

- ↑ http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/145/4/284

- ↑ "FDA approved labeling for Neurontin capsules, tablets, and oral solution" (PDF). February 2005. Check date values in:

|date=(help) Note that an updated labeling has been approved, but is not available online as of November 2006 - ↑ Maria C Lasso-de-la-Vega Pharm.D (2001). "Gabapentin-associated hepatotoxicity" (Abstract). Am J Gastroenterol. 96 (12): 3460–3462. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ↑ Ayhan DOGUKAN (2006). "Gabapentin-induced coma in a patient with renal failure" (Abstract). Hemodialysis International. 10 (2): 168–169. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ↑ Bookwalter T, Gitlin M (2005). "Gabapentin-induced neurologic toxicities" (Abstract). Pharmacotherapy. 25 (12): 1817–9. PMID 16305301. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ↑ http://www.iguard.org/drugs/NEURONTIN.html

External links

- Pages with script errors

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- Pages using citations with format and no URL

- Pages using citations with accessdate and no URL

- CS1 errors: dates

- Pages with broken file links

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- E number from Wikidata

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2007

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Anticonvulsants

- Mood stabilizers