Dressler's syndrome

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mohammed A. Sbeih, M.D.[2] Phone:617-849-2629; Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [3]

Synonyms and keywords: Postmyocardial infarction syndrome; PMIS; post-cardiac injury syndrome

Overview

Dressler's syndrome or post myocardial infarction syndrome is a form of pericarditis that occurs in the setting of injury to the heart as a result of myocardial infarction. Dressler's syndrome typically occurs 2 to 10 weeks after myocardial infarction[1]. This differentiates Dressler's syndrome from the much more common post myocardial infarction pericarditis which occurs between days 2 and 4 after myocardial infarction.

Historical Perspective

It was first characterized by William Dressler in 1956.[2][3][4][5] It should not be confused with the Dressler's syndrome of hemoglobinuria named for Lucas Dressler, who characterized it in 1854.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Dressler's syndrome is believed to result from an autoimmune inflammatory reaction to myocardial neo-antigens. It usually occurs within weeks or months of the Infarction due to antimyocardial antibodies, this begins with myocardial injury that releases cardiac antigens and stimulates antibody formation. The immune complexes that are generated then deposit onto the pericardium and causes the inflammation . The autoimmune response and syndrome may also appear after pulmonary embolism.[8]

Viruses that have been associated with Dressler Syndrome include

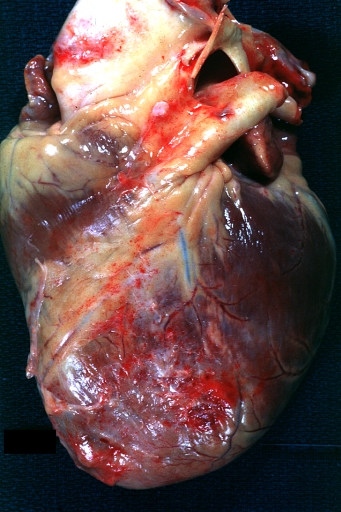

Gross Pathology Images

Causes

Differentiating Dressler's syndrome from other Conditions

- Dressler's syndrome typically occurs 2 to 10 weeks after a myocardial infarction has occurred[9].

- This differentiates Dressler's syndrome from the much more common post myocardial infarction pericarditis that occurs in 17% to 25% of cases of acute myocardial infarction between days 2 and 4 after the myocardial infarction.

- Dressler's syndrome also needs to be differentiated from pulmonary embolism, another identifiable cause of pleuritic (and non-pleuritic) chest pain in people who have been hospitalized and/or undergone surgical procedures within the preceding weeks.

- Congestive Heart Failure

- Influenza

- Acute anemia with or without GI bleed

- Uremia

Epidemiology and Demographics

In the setting of myocardial infarction, Dressler's syndrome occurs in about 7% of cases[10]. Dressler's syndrome was more commonly seen in the era prior to reperfusion, but its incidence has markedly decreased in the reperfusion era, presumably because of smaller infarct sizes [11].

Natural History, Complications, Prognosis

- Pericardial effusion may result from the accumulation of fluids as a result of inflammation in the pericardial sac.

- Cardiac tamponade can occur if the accumulation of fluids in the pericardium is large enough and rapid enough.Classic findings of tamponade include Beck's triad:

- Low blood pressure

- Distended neck veins (JVD)

- Muffled/distant heart tones

- Constrictive pericarditis can occur if there is a chronic inflammatory response

Diagnosis

Symptoms

The syndrome consists of a persistent low-grade fever, and chest pain which is usually pleuritic in nature.

- Malaise/generalized weakness

- Irritability

- Decreased appetite

- Dyspnea (with or without hypoxia)

- Palpitations/tachycardia

- Arthralgias

The symptoms tend to occur after a few weeks or even months after myocardial infarction and tend to subside in a few days.

Physical Examination

Cardiovascular Examination

- A pericardial friction rub, and /or a pericardial effusion is present.

- On physical examination, often tachycardic with a pericardial friction rub heard on auscultation. This characteristic pericardial friction rub may disappear.

- This can be secondary to either improvement in or worsening of accumulation of pericardial fluid.

- Additionally, patients may present with pulsus paradoxus (greater than 10 mmHg decrease in blood pressure with inspiration, and decreased pulse amplitude palpated on the radial artery).

- Some patients with DS may exhibit signs of pneumonitis (e.g., a cough, decreased oxygen saturation, fever).

- The pulmonary component to symptoms can be minimal with no pulmonary complaints, ranging all the way to significant respiratory distress with large pulmonary effusions.

Laboratory Findings

Elevated ESR.

Imaging Findings

- An echo will allow for evaluation of the pericardial fluid, if present, and help discern the exact cause of reduced cardiac output (i.e., determine whether truly DS or another condition such as congestive heart failure).

- An echo will further allow for evaluation of ventricular contractility, in addition to assessment of the potential risk of cardiac tamponade (i.e., if cardiac chambers appear compressed by pericardial fluid). The more pericardial fluid that is accumulated, the easier it is to detect its presence by echocardiography.[12]

- Whilst definitive evaluation with formal echocardiogram is the gold standard, bedside cardiac ultrasound.

- If it is difficult to assess the posterior pericardium with an echo, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may employed to determine whether there is an effusion present. In some instances, fluid collections become loculated. [13]

- A chest x-ray will reveal flattening of the costophrenic angles and be employed if echocardiography is not available enlargement of the cardiac silhouette as a result of both pleural and pericardial effusions.[14]

- An electrocardiograph (ECG) initially demonstrate ST segment elevation and T-wave inversion, such as with pericarditis. Further inflammation of the myocardium will also result in ST segment elevations. Both electrical alternans (variation in amplitude or directionality of QRS from beat to beat) and/or a low voltage QRS.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

Dressler's syndrome is typically treated with high dose (up to 650 mg PO q 4 to 6 hours) enteric-coated aspirin. Acetaminophen can be added for pain management as this does not affect the coagulation system. Anticoagulants should be discontinued if the patient develops a pericardial effusion.[15]

NSAIDs such as ibuprofen should be avoided in the peri-infarct period as they:

- Increase the risk of reinfarction

- Adversely impact left ventricular remodeling

- Block the effectiveness of aspirin

2013 Revised ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (DO NOT EDIT)[16]=

Management of Pericarditis After STEMI (DO NOT EDIT)[16]

| Class I |

| "1. Aspirin is recommended for treatment of pericarditis after STEMI.[17](Level of Evidence: B)" |

| Class III (Harm) |

| "1. Glucocorticoids and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are potentially harmful for treatment of pericarditis after STEMI. [18][19](Level of Evidence: B)" |

| Class IIb |

| "1. Administration of acetaminophen, colchicine, or narcotic analgesics may be reasonable if aspirin, even in higher doses, is not effective. (Level of Evidence: B)" |

Sources

- The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction [20]

- The 2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction [21]

References

- ↑ Krainin F, Flessas A, Spodick D (1984). "Infarction-associated pericarditis. Rarity of diagnostic electrocardiogram". N Engl J Med. 311 (19): 1211–4. PMID 6493274.

- ↑ DRESSLER W (1956). "A post-myocardial infarction syndrome; preliminary report of a complication resembling idiopathic, recurrent, benign pericarditis". J Am Med Assoc. 160 (16): 1379–83. PMID 13306560.

- ↑ Bendjelid K, Pugin J (2004). "Is Dressler syndrome dead?". Chest. 126 (5): 1680–2. doi:10.1378/chest.126.5.1680. PMID 15539743. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Streifler J, Pitlik S, Dux S; et al. (1984). "Dressler's syndrome after right ventricular infarction". Postgrad Med J. 60 (702): 298–300. PMC 2417818. PMID 6728756. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Dressler W (1959). "The post-myocardial-infarction syndrome: a report on forty-four cases". AMA Arch Intern Med. 103 (1): 28–42. PMID 13605300. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Template:WhoNamedIt

- ↑ L. A. Dressler. Ein Fall von intermittirender Albuminurie und Chromaturie. Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin, 1854, 6: 264-266.

- ↑ Jerjes-Sánchez C, Ramírez-Rivera A, Ibarra-Pérez C (1996). "The Dressler syndrome after pulmonary embolism". Am J Cardiol. 78 (3): 343–5. PMID 8759817.

- ↑ Krainin F, Flessas A, Spodick D (1984). "Infarction-associated pericarditis. Rarity of diagnostic electrocardiogram". N Engl J Med. 311 (19): 1211–4. PMID 6493274.

- ↑ Krainin F, Flessas A, Spodick D (1984). "Infarction-associated pericarditis. Rarity of diagnostic electrocardiogram". N Engl J Med. 311 (19): 1211–4. PMID 6493274.

- ↑ Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH, Willich SN, Davis VG, Poole WK; et al. (1989). "Pericarditis in acute myocardial infarction: characterization and clinical significance". Am Heart J. 117 (1): 86–92. PMID 2643287.

- ↑ Wessman DE, Stafford CM (March 2006). "The postcardiac injury syndrome: case report and review of the literature". South. Med. J. 99 (3): 309–14. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000203330.15503.0b. PMID 16553111.

- ↑ Scarfone RJ, Donoghue AJ, Alessandrini EA (August 2003). "Cardiac tamponade complicating postpericardiotomy syndrome". Pediatr Emerg Care. 19 (4): 268–71. doi:10.1097/01.pec.0000092573.40174.74. PMID 12972828.

- ↑ Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, Sinak LJ, Hayes SN, Melduni RM, Oh JK (June 2010). "Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management". Mayo Clin. Proc. 85 (6): 572–93. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0046. PMC 2878263. PMID 20511488.

- ↑ Jaworska-Wilczynska M, Abramczuk E, Hryniewiecki T (November 2011). "Postcardiac injury syndrome". Med. Sci. Monit. 17 (11): CQ13–14. doi:10.12659/msm.882029. PMID 22037738.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD; et al. (2012). "2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84. PMID 23247303. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Berman J, Haffajee CI, Alpert JS (1981). "Therapy of symptomatic pericarditis after myocardial infarction: retrospective and prospective studies of aspirin, indomethacin, prednisone, and spontaneous resolution". Am. Heart J. 101 (6): 750–3. PMID 7234652. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Bulkley BH, Roberts WC (1974). "Steroid therapy during acute myocardial infarction. A cause of delayed healing and of ventricular aneurysm". Am. J. Med. 56 (2): 244–50. PMID 4812079. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Silverman HS, Pfeifer MP (1987). "Relation between use of anti-inflammatory agents and left ventricular free wall rupture during acute myocardial infarction". Am. J. Cardiol. 59 (4): 363–4. PMID 3812291. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Hand M, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC, Alpert JS, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Gregoratos G, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK (2004). "ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction)". Circulation. 110 (9): e82–292. PMID 15339869. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW; et al. (2008). "2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration With the Canadian Cardiovascular Society endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians: 2007 Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Writing on Behalf of the 2004 Writing Committee". Circulation. 117 (2): 296–329. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188209. PMID 18071078. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)