Diphtheria historical perspective

|

Diphtheria Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Diphtheria historical perspective On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Diphtheria historical perspective |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Diphtheria historical perspective |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Luke Rusowicz-Orazem, B.S.

Overview

Diphtheria was first identified in 1826 by French physician Pierre Bretonneau. Before its official discovery, diphtheria was prevalent in 18th- and 19th-century society. Between 1735 and 1740, a diphtheria epidemic in the New England colonies was thought to be responsible for the death of 80% of children under 10 years of age in select towns. During the late 19th century, diphtheria was also prevalent in the British royal family. In the 1920s, there were an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 cases of diphtheria per year in the United States, which resulted in between 13,000 and 15,000 deaths. In the 1880s, one of the first effective treatments for diphtheria was discovered by French physician Eugène Bouchut and American physician Joseph O'Dwyer: tubes that were inserted into the throat, preventing patients from suffocating due to the membrane sheath that would otherwise obstruct airways. In the 1890s, German physician Emil von Behring developed the first antitoxin serum therapy that neutralized the diphtheria toxins in the bodies of patients. Americans William H. Park and Anna Wessels Williams and Pasteur Institute scientists Emile Roux and Auguste Chaillou also independently developed diphtheria antitoxin in the 1890s. In 1923, the first successful vaccine for diphtheria was developed by French biologist Gaston Ramon. The emergence of sulfa drugs in the post-World War II era led to the adoption of penicillin as the first successful anti-diphtheria antibiotic treatment. In 1968, the WHO established recommendations for the production and quality control of diphtheria vaccines. In 1974, the WHO included the DPT vaccine in their Expanded Programme on immunization for developing countries.

Discovery

- Diphtheria was first identified in 1826 by French physician Pierre Bretonneau.[1]

- The name alludes to the leathery, sheath-like membrane that grows on the tonsils, throat, and in the nose of affected patients.[2][3]

Impact on Cultural History

- Between 1735 and 1740, a diphtheria epidemic in the New England colonies was thought to be responsible for the death of 80% of children under 10 years of age in select towns.[4]

- During the late 19th century, diphtheria was also prevalent in the British royal family.[5]

- Famous cases included a daughter and granddaughter of Britain's Queen Victoria.

- Princess Alice of Hesse, the second daughter of Queen Victoria, died of diphtheria after she contracted it from her children in December 1878.

- One of Princess Alice's daughters, Princess May, died of diphtheria in November of 1878.[5]

- In the 1920s, there were an estimated 100,000-200,000 cases of diphtheria per year in the United States, which resulted in between 13,000 and 15,000 deaths.[6]

- Children represented a large majority of these cases and fatalities.

- One of the most notable outbreaks of diphtheria occurred in Nome, Alaska in 1925; the trip made to get the antitoxin is now celebrated by the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race.[7]

Landmark Events in the Development of Treatment Strategies

- In the 1880s, one of the first effective treatments for diphtheria was discovered by French physician Eugène Bouchut and American physician Joseph O'Dwyer: tubes that were inserted into the throat, preventing affected patients from suffocating due to the membrane sheath that would otherwise obstruct airways.[8]

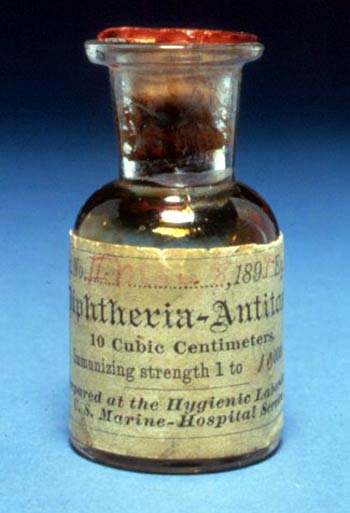

- In the 1890s, the German physician Emil von Behring developed the first antitoxin serum therapy that neutralized the diphtheria toxins in the body.[9]

- Americans William H. Park and Anna Wessels Williams and Pasteur Institute scientists Emile Roux and Auguste Chaillou also independently developed diphtheria antitoxin in the 1890s.[10][11][12]

- In 1923, the first successful vaccine for diphtheria was developed by French biologist Gaston Ramon.[13]

- The emergence of sulfa drugs in the post-World War II era led to the adoption of penicillin as the first successful anti-diphtheria antibiotic treatment.[14]

- In 1968, the WHO established recommendations for the production and quality control of diphtheria vaccines.[15]

- In 1974, the WHO included the DPT vaccine in their expanded Programme on immunization for developing countries.[15]

References

- ↑ Nahmias, André J. (2013). Immunology of Human Infection: Part I: Bacteria, Mycoplasmae, Chlamydiae, and Fungi. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 171. ISBN 1468410091.

- ↑ Pierre Bretonneau, Des inflammations spéciales du tissu muqueux, et en particulier de la diphtérite, ou inflammation pelliculaire, connue sous le nom de croup, d'angine maligne, d'angine gangréneuse, etc. [Special inflammations of mucous tissue, and in particular diphtheria or skin inflammation, known by the name of croup, malignant throat infection, gangrenous throat infection, etc.] (Paris, France: Crevot, 1826).

A condensed version of this work is available in: P. Bretonneau (1826) "Extrait du traité de la diphthérite, angine maligne, ou croup épidémique" (Extract from the treatise on diphtheria, malignant throat infection, or epidemic croup), Archives générales de médecine, series 1, 11 : 219-254. From p. 230: " … M. Bretonneau a cru convenable de l'appeler diphthérite, dérivé de ΔΙΦθΕΡΑ, … " ( … Mr. Bretonneau thought it appropriate to call it diphtheria, derived from ΔΙΦθΕΡΑ [diphthera], … ) - ↑ "Diphtheria". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ Caulfield, Ernest. (1949) "A True History of the Terrible Epidemic Vulgarly Called the Throat Distemper, Which Occurred in His Majesty's New England Colonies between the Years 1735 and 1740." The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., Vol 6, No 2. p. 338. See Also: Shulman, Stanford (2004) The History of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Html by Google) Pediatric Research. Vol. 55, No. 1

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Princess Alice of Hesse and by Rhine - Blog & Alexander Palace Time Machine".

- ↑ "Pinkbook | Diphtheria | Epidemiology of Vaccine Preventable Diseases | CDC".

- ↑ Wilson WH (1986). "The serum dash to Nome, 1925: the making of Alaskan heroes". Alaska J. 16: 250–9. PMID 11616478.

- ↑ Sperati G, Felisati D (2007). "Bouchut, O'Dwyer and laryngeal intubation in patients with croup". Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 27 (6): 320–3. PMC 2640059. PMID 18320839.

- ↑ Raju TN (2006). "Emil Adolf von Behring and serum therapy for diphtheria". Acta Paediatr. 95 (3): 258–9. doi:10.1080/08035250600580586. PMID 16497632.

- ↑ Oliver, Wade W. (1940). "BIOGRAPHY OF DR. WILLIAM H. PARK". Journal of the American Medical Association. 114 (14). doi:10.1001/jama.1940.02810140092030. ISSN 0002-9955.

- ↑ "Changing the Face of Medicine | Dr. Anna Wessels Williams".

- ↑ Gluud C (2011). "Danish contributions to the evaluation of serum therapy for diphtheria in the 1890s". J R Soc Med. 104 (5): 219–22. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k073. PMC 3089870. PMID 21558100.

- ↑ ROGERS FB, MALONEY RJ (1963). "GASTON RAMON, 1886-1963". Arch. Environ. Health. 7: 723–5. PMID 14077224.

- ↑ "Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Control of Infectious Diseases".

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "WHO | Diphtheria".