Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Ilan Dock, B.S.

Overview

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a widespread tick-borne viral disease, a zoonosis of domestic animals and wild animals, that may affect humans. The pathogenic virus, especially common in East and West Africa, is a member of the Bunyaviridae family of RNA viruses. Clinical disease is rare in the majority of infected mammals, but commonly severe in infected humans, with a 30% mortality rate. Outbreaks of illness are usually attributed to handling the bodily fluids of infected animals or people.

Differentiating Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever from other Diseases

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever should be differentiated from the following diseases:

| Disease | Organism | Vector | Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Infection | ||||

| Borreliosis (Lyme Disease) [1] | Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex and B. mayonii | I. scapularis, I. pacificus, I. ricinus, and I. persulcatus | Erythema migrans, flu-like illness(fatigue, fever), Lyme arthritis, neuroborreliosis, and carditis. | |

| Relapsing Fever [2] | Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF): | Borrelia duttoni, Borrelia hermsii, and Borrelia parkerii | Ornithodoros species | Consistently documented high fevers, flu-like illness, headaches, muscular soreness or joint pain, altered mental status, painful urination, rash, and rigors. |

| Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) : | Borrelia recurrentis | Pediculus humanus | ||

| Typhus (Rickettsia) | ||||

| Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor andersoni | Fever, altered mental status, myalgia, rash, and headaches. | |

| Helvetica Spotted Fever [3] | Rickettsia helvetica | Ixodes ricinus | Rash: spotted, red dots. Respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough), muscle pain, and headaches. | |

| Ehrlichiosis (Anaplasmosis) [4] | Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii | Amblyomma americanum, Ixodes scapularis | Fever, headache, chills, malaise, muscle pain, nausea, confusion, conjunctivitis, or rash (60% in children and 30% in adults). | |

| Tularemia [5] | Francisella tularensis | Dermacentor andersoni, Dermacentor variabilis | Ulceroglandular, glandular, oculoglandular, oroglandular, pneumonic, typhoidal. | |

| Viral Infection | ||||

| Tick-borne meningoencephalitis [6] | TBEV virus | Ixodes scapularis, I. ricinus, I. persulcatus | Early Phase: Non-specific symptoms including fever, malaise, anorexia, muscle pains, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. Second Phase: Meningitis symptoms, headache, stiff neck, encephalitis, drowsiness, sensory disturbances, and potential paralysis. | |

| Colorado Tick Fever [7] | CTF virus | Dermacentor andersoni | Common symptoms include fever, chills, headache, body aches, and lethargy. Other symptoms associated with the disease include sore throat, abdominal pain, vomiting, and a skin rash. A biphasic fever is a hallmark of Colorado Tick Fever and presents in nearly 50% of infected patients. | |

| Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever | CCHF virus | Hyalomma marginatum, Rhipicephalus bursa | Initially infected patients will likely feel a few of the following symptoms: headache, high fever, back and joint pain, stomach pain, vomiting, flushed face, red throat petechiae of the palate, and potentially changes in mood as well as sensory perception. | |

| Protozoan Infection | ||||

| Babesiosis [8] | Babesia microti, Babesia divergens, Babesia equi | Ixodes scapularis, I. pacificus | Non-specific flu-like symptoms. | |

Epidemiology

- Sporadic infection of people is usually caused by Hyalomma tick bite.

- Clusters of illness typically appear after people treat, butcher, or eat infected livestock. Particularly ruminants and ostriches.

- Outbreaks have occurred in clinical facilities where health workers have been exposed to infected blood and fomites.

- On July 28, 2005 authorities reported 41 cases of CCHF in Turkey's Yozgat Province, with one death.

Endemic Regions

- Endemic areas include Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, a belt across central Africa and South Africa and Madagascar.

- Main environmental reservoir for the virus are small mammals (particularly European hare, Middle-African hedgehogs and multimammate rats).

Notable outbreaks

- During the summers of 1944 and over 200 cases of an acute, hemorrhagic, febrile illness occurred in Soviet troops rescuing the harvest following the ethnic cleansing of the Crimean Tatars.

- Virus was discovered in blood samples of patients and in the tick Hyalomma marginatum marginatum.

- Researchers soon recognized that a similar disease had been occurring in the Central Asian Republics.

Causes

Life Cycle and Spread of Disease

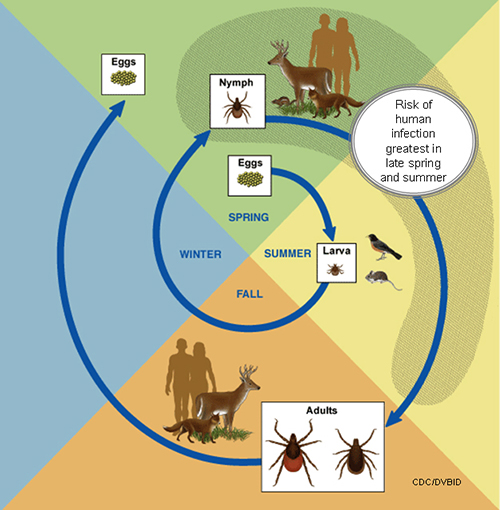

General Tick Life Cycle [9]

- A tick's life cycle is composed of four stages: hatching (egg), nymph (six legged), nymph (eight legged), and an adult.

- Ticks require blood meal to survive through their life cycle.

- Hosts for tick blood meals include mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Ticks will most likely transfer between different hosts during the different stages of their life cycle.

- Humans are most often targeted during the nymph and adult stages of the life cycle.

- Life cycle is also dependent on seasonal variation.

- Ticks will go from eggs to larva during the summer months, infecting bird or rodent host during the larval stage.

- Larva will infect the host from the summer until the following spring, at which point they will progress into the nymph stage.

- During the nymph stage, a tick will most likely seek a mammal host (including humans).

- A nymph will remain with the selected host until the following fall at which point it will progress into an adult.

- As an adult, a tick will feed on a mammalian host. However unlike previous stages, ticks will prefer larger mammals over rodents.

- The average tick life cycle requires three years for completion.

- Different species will undergo certain variations within their individual life cycles.

Spread of Tick-borne Disease

- Ticks require blood meals in order to progress through their life cycles.

- The average tick requires 10 minutes to 2 hours when preparing a blood meal.

- Once feeding, releases anesthetic properties into its host, via its saliva.

- A feeding tube enters the host followed by an adhesive-like substance, attaching the tick to the host during the blood meal.

- A tick will feed for several days, feeding on the host blood and ingesting the host's pathogens.

- Once feeding is completed, the tick will seek a new host and transfer any pathogens during the next feeding process. [9]

Virology

- Nairovirus in the family of Bunyaviridae.

Transmission

- Ixodid ticks, of the Hyalomma genus, are the primary vector and reservoir of infection.

- Human transmission occurs through human contact with infected animal or human blood and body fluids.

History and Symptoms

- Typically, after a 1–3 day incubation period following a tick bite (5–6 days after exposure to infected blood or tissues), flu-like symptoms appear, which may resolve after one week.

- In up to 75% of cases, however, signs of hemorrhage appear within 3–5 days of the onset of illness: first mood instability, agitation, mental confusion and throat petechiae, then soon nosebleeds, bloody urine and vomiting, and black stools.

- The liver becomes swollen and painful.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation may occur as well as acute kidney failure and shock, and sometimes acute respiratory distress syndrome.

- Patients usually begin to recover after 9–10 days from symptom onset, but 30% die in the second week of illness.

Laboratory diagnostics

- ELISA, RT-PCR, antibody titers, immunohistochemical staining, and virus isolation attempts are all laboratory tests to assist in the diagnosis of a potential Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever.

- An ELISA may be used for diagnosis during the acute phase of infection.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction may be used to identify viral RNA sequences in the blood or tissues collected.

Treatment

- Treatment is primarily symptomatic and supportive, as there is no established specific treatment.

- Ribavirin is effective in vitro[10] and has been used during outbreaks,[11] but there is no trial evidence to support its use.

Risk Factors

Endemic Areas

- Travelling through endemic areas increase the risk of infection.

- Endemic areas include Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, a belt across central Africa and South Africa and Madagascar.

Livestock

- Sheep, goats and cattle develop high titers of virus in blood, but tend not to fall ill.

- Transmission may occur through unprotected contact with blood and other body fluids of an infected animal.

Occupational

- The following individuals are at a higher risk of infection in endemic areas:

- Livestock workers

- Animal herders

- Slaughterhouse workers

Prevention

Limiting tick exposure

It is unreasonable to assume that a person can completely eliminate activities that may result in tick exposure. Therefore, prevention measures should emphasize personal protection when exposed to natural areas where ticks are present:

- Wear light-colored clothing which allows you to see ticks that are crawling on your clothing.

- Tuck your pants legs into your socks so that ticks cannot crawl up the inside of your pants legs.

- Apply repellents to discourage tick attachment. Repellents containing permethrin can be sprayed on boots and clothing, and will last for several days. Repellents containing DEET (n, n-diethyl-m-toluamide) can be applied to the skin, but will last only a few hours before reapplication is necessary. Use DEET with caution on children. Application of large amounts of DEET on children has been associated with adverse reactions.

- Conduct a body check upon return from potentially tick-infested areas by searching your entire body for ticks. Use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body. Remove any tick you find on your body.

- Parents should check their children for ticks, especially in the hair, when returning from potentially tick-infested areas.

- Ticks may also be carried into the household on clothing and pets and only attach later, so both should be examined carefully to exclude ticks.[7]

Public health measures

- Where mammal and tick infection is common agricultural regulations require de-ticking farm animals before transportation or delivery for slaughter.

- Personal tick avoidance measures are recommended, such as use of insect repellents, adequate clothing and body inspection for adherent ticks.

- When feverish patients with evidence of bleeding require resuscitation or intensive care, body substance isolation precautions should be taken.

- The United States armed forces maintain special stocks of ribavirin to protect personnel deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq from CCHF.

External links

- Ergönül O. (2006). "Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever". Lancet Infect Dis. 6: 203–214. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70435-2.

- World Health Organization Fact Sheet

Gallery

-

Isolated male patient diagnosed with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (C-CHF). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [12]

-

Cytoarchitectural changes found in a liver tissue specimen extracted from a Congo/Crimean hemorrhagic fever patient (280X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [12]

-

Cytoarchitectural changes found in a liver tissue specimen extracted from a Congo/Crimean hemorrhagic fever patient (400X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [12]

References

- ↑ Lyme Disease Information for HealthCare Professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Relapsing Fever Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/ Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/ Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Disease index General Information (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/babesiosis/health_professionals/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). \http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ General Disease Information (TBE). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/tbe/ Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 General Tick Deisease Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/coloradotickfever/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Babesiosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/babesiosis/disease.htmlAccessed December 8, 2015.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Life Cycle of Ticks that Bite Humans (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Watts DM, Ussery MA, Nash D, Peters CJ. (1989). "Inhibition of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever viral infectivity yields in vitro by ribavirin". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 41: 581–85. PMID 2510529.

- ↑ Ergönül Ö, Celikbas A, Dokuzoguz B; et al. (2004). "The chacteristics of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in a recent outbreak in Turkey and the impact of oral ribavirin therapy". Clin Infect Dis. 39: 285–89. doi:10.1086/422000.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

de:Krim-Kongo-Fieber fa:تب خونریزیدهنده کریمه کنگو

![Isolated male patient diagnosed with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (C-CHF). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [12]](/images/6/60/Crimean_congo_hemorrhagic_fever03.jpeg)

![Cytoarchitectural changes found in a liver tissue specimen extracted from a Congo/Crimean hemorrhagic fever patient (280X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [12]](/images/6/67/Crimean_congo_hemorrhagic_fever02.jpeg)

![Cytoarchitectural changes found in a liver tissue specimen extracted from a Congo/Crimean hemorrhagic fever patient (400X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [12]](/images/6/65/Crimean_congo_hemorrhagic_fever01.jpeg)