Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mahmoud Sakr, M.D. [2] ,Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [3] , Edzel Lorraine Co, D.M.D., M.D. [4]

Overview Several measures [1] diuretics and safety of their usage is an important aspect of the treatment that should be closely monitored along with daily measurement of weight and moderate sodium restriction. Physical activity is highly recommended, although heavy labor or sports shouldn’t be a part of it. A reduction in physical activity promotes physical deconditioning, and an increase of weight which may be associated with more strain on the failing heart.[2] HF are also recommended to be immunized with influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in order to reduce the risk of respiratory infection .

Drugs that should be Avoided or Used with Caution in Patients with HF Pharmacological therapy should be closely monitored and several classes of drugs should be avoided in case of HF:

Calcium Channel blockers : There is no direct role of these drugs in the management of HF, due to negative and possible deleterious effect in patients with HF due to systolic dysfunction[3] amlodipine and felodipine have not been linked to adverse effect in HF treatment, but there is no evidence of efficacy for these drugs in the management of HF.[4] amlodipine and felodipine appear to be safe for the treatment of concomitant disease in HF patients, such as angina or hypertension .Antiarrhythmic agents : Negative inotropic effect exerted by most antiarrhythmic drugs can precipitate HF in patients with reduced LV function. The reduction in LV function can also reduce the elimination of these drugs leading to further drug toxicity. Other antiarrhythmic drugs can induce some proarrhythmic effect, especially class 1 agents and class 3 agents Ibutilide and sotalol ;[5] dofetilide can induce torsades to pointes .Amiodarone is considered the safest of the antiarrhythmic drugs because of its minimal proarrhythmic effect and is generally the preferred drug for treating arrhythmias in HF patients.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID):[6] NSAIDs in HF patients is linked with an increased risk of HF exacerbation, increased renal dysfunction, and abnormal responses to ACEIs and diuretics . COX-2 selective inhibitors have not been fully investigated, but observational studies indicate that they may be linked with an increased rate of HF exacerbation and increased mortality.Aspirin benefits and risks are not well established in patients with HF and Vascular disease (includingCAD ). The potential interaction between ACEIs and beta blockers is of great importance. Although no data has proven that aspirin causes more frequent HF exacerbations and interactions with those drugs, health care providers should be aware of the possibility of such risks, but no recommendation for or against aspirin therapy in patients with heart failure can be made before further data are available.

Metformin - one of the most common side effects of metformin is lactic acidosis , which can be fatal in patients with HF.

Thiazolidinediones -[8]

PDE-5 inhibitors such as sildenafil , vardenafil , and tadalafil , are widely used in the management of erectile dysfunction in men. The use of those agents with any form of nitrate therapy is contraindicated because of severe hypotensive effect that can be life threatening.[13] hypotension was observed, but HF patients with borderline low blood pressure and/or low volume status are in risk of severe hypotension and should avoid any PDE-5 inhibitors use.

Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha inhibitors TNF-alpha : New onset or worsening of pre-existing heart failure have been linked to TNF-alpha inhibitors.[15] Infliximab has been specifically contraindicated in doses over 5mg/kg in patients with heart failure.Serum potassium should be closely monitored in HF patients, in order of preventing either hypokalemia or hyperkalemia , which could greatly affect cardiac excitability and conduction, leading to sudden cardiac death .[17] potassium should be maintained between 4.0 to 5.0 mEq per liter range, because low potassium level may affect digitalis and antiarrhythmic drugs treatment, while high potassium level can prevent the use of treatments known to prolong life.[17]

Supervision of HF patients with close monitoring of treatment and diet is a very important aspect of the follow-up process in those individuals. Body weight and medications should be closely monitored, because any minor change in those parameters can have a significant effect over symptoms and hospitalization of patients with HF.[18] [19]

Pharmacological Therapy of HF Improving symptoms, reducing mortality and slowing or reversing myocardial deterioration are the main goals of pharmacological therapy in HF patients. The therapy should be also directed at preventing arrhythmias, embolic events and other exacerbating factors.

Different strategies have been implemented in the treatment of HF, but the ACC/AHA recommendations are based on a combination of 3 types of drugs: a Diuretic , an ACEI or an ARB , and a beta blocker [20] euvolemic state. On the other hand, ACEI and a beta blocker should be started and maintained in patients who can tolerate them because of their major effect in controlling symptoms and reducing mortality. Digoxin can be added to this regime as a fourth agent to reduce symptoms, reduce recurrent hospitalization, control great and rhythm, and enhance exercise tolerance.

Diuretics Different classes of diuretics have been implicated in the treatment of CHF . Loop Diuretics such as furosemide , bumetanide and torsemide , act on the inhibition of sodium and chloride reabsorption in the loop of Henle , whereas thiazide diuretics , metolazone , and potassium sparing diuretics as spironolactone act on the distal portion of the renal tubule .

[21] Loop diuretics increase sodium secretion up to 25 % of the filtered load of sodium, enhance free water clearance and maintain their efficacy unless severe renal impairment is present.[22] Thiazide diuretics in contrast, increase the fractional excretion of sodium to a maximum of 10% of the filtered load, decrease free water clearance and lose their efficacy in patients with impaired renal function . For such reasons, loop diuretics are much preferred, unless hypertension with mild fluid retention is present in HF patients, where thiazide diuretics may have a better antihypertensive effect in this case.

Different short-studies demonstrated the efficacy of diuretics in improving various symptoms of HF, reducing jugular venous pressure , pulmonary congestion , peripheral edema and body weight, all within days of initiation of therapy.[23] diuretic therapy on morbidity and mortality, but an improvement in cardiac function and exercise tolerance in patients with HF have been demonstrated in intermediate-term trials.[24]

Diuretics produce great symptomatic benefits,[25] pulmonary edema and peripheral edema within hours or days. However, Diuretics should not be used alone in controlling Stage C HF. They should be combined with an ACEI and a beta blocker to avoid further clinical deterioration and maintain the HF symptoms under control.[24]

Appropriate dose of diuretics should used in treatment of HF,[26] ACEIs and ARBs and an increase risk of decompensation with the use of beta blockers , while excessive diuretics will lead to volume contraction which can increase the risk of hypotension and renal insufficiency with ACEIs , ARBs and beta blockers .[27]

Loop diuretics are usually the first diuretics to be used to control pulmonary and/or peripheral edema . Furosemide is the most commonly used, but some patients may respond favorably to other agents in this category (as torsemide and Bumetanide ) because of superior absorption and longer time of action.[28]

The starting dosage is usually 20 to 40 mg of furosemide or its equivalent, but the exact dosing should always be monitored according to diuresis and other clinical symptoms, since the ultimate goal is to eliminate the evidence of fluid retention such as jugular venous pressure elevation and peripheral edema . Outpatients with HF are usually started with low dose until urine increases and weigh decreases by 0.5 to 1.0 kg daily. Diuretic therapy should be also combined with moderate dietary sodium restriction.

Unstable or severe disease, should be controlled with intravenous diuretics ( bolus or continuous infusion ) and thiazide diuretics can be added for a synergistic effect.[29]

Reducing overall volume may decrease intracardiac filling pressure resulting in a lower cardiac output via the Frank-Starling relationship. This effect is usually a minor effect and does not alter the course of the therapy. On the other hand, an unexplained increase in BUN and creatinine should be closely monitored and suspected as a sign of abnormal tissue perfusion. In this case renal function and other end organ perfusion should be assessed to avoid any concomitant complications.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Patients with moderate to severe HF or asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction show a great improvement in survival rate with the usage of ACE inhibitors .[30] kinins and augment kinin -mediated prostaglandin production, so the effect of ACEIs cannot be solely explained by the suppression of Angiotensin II production. Furthermore, it has been proven that ACEIs modify cardiac remodeling more favorably than ARBs in experimental models of HF.[31] ACEIs can alleviate symptoms,[32]

Another important aspect of ACEIs therapy is the reduction of mortality and hospitalization in such patients.[33] CAD . In general ACEIs should be used together with a beta blocker and should not be used without diuretics in patients with a current or recent history of fluid retention, because of the important role of diuretics in maintaining sodium balance and preventing the development of peripheral and pulmonary edema .[24]

For the reasons mentioned above, ACEI therapy should be started in asymptomatic or symptomatic patients with HF. The beginning therapy should be a low dose ( eg, 2.5 mg of enalapril twice a day, 6.25 mg of captopril three time a day or 5 mg of lisinopril once a day). The dose should be gradually increased in one to two week if the initial therapy is tolerated and try to target a dose of 20 mg of enalapril twice a day, or 50 mg of captopril three times a day or up to 40 mg of lisinopril a day.[34] [35]

NSAIDs should be avoided since they may cause an increase in adverse effects of ACEIs in patients with HF and a decrease in the favorable effect of ACEIs therapy.[24] aspirin may inhibit the acute hemodynamic benefits of ACEIs .[36] CAD ) then use of ASA along with ACEIs is recommended. However, but in patients with no history of CAD , there is no evidence to support the use of aspirin .

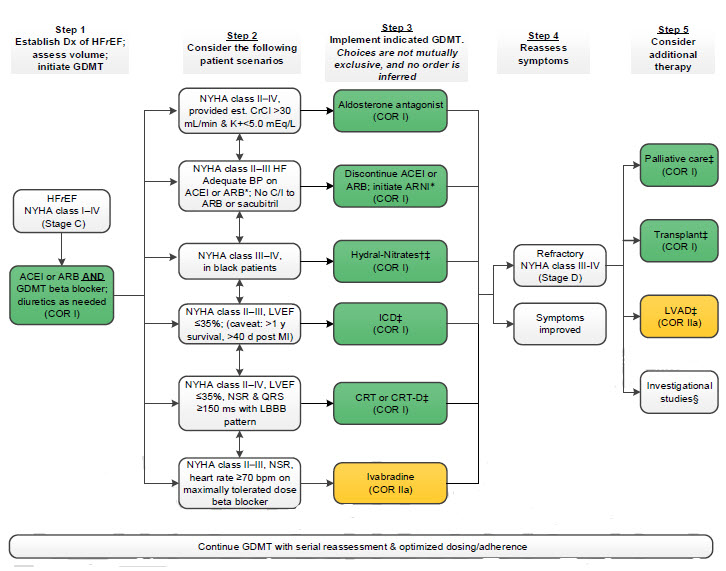

Treatment of HFrEF Stage C and D Abbreviations:

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB: angiotensin receptor-blocker, ARNI: angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibitor, BP: blood pressure, bpm: beats per minute, C/I: contraindication, COR: Class of

Recommendation, NT-proBNP: creatinine clearance, NYHA: cardiac resynchronization therapy–device, pts: diagnosis, HF: guideline-directed management and therapy, CrCl: creatinine clearance, CRT-D: cardiac resynchronization therapy–device, Dx: diagnosis, GDMT: guideline-directed management and therapy, HF: heart failure, HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, ISDN/HYD: isosorbide dinitrate hydral-nitrates, K+: potassium, LBBB: left bundle-branch block, LVAD: left ventricular assist device, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, MI: myocardial infarction, NSR: normal sinus rhythm, NYHA: New York Heart Association

†Hydral-Nitrates green box: The combination of ISDN/HYD with ARNI has not been robustly tested. BP response should be carefully monitored.

2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Heart Failure Guideline/ 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure/2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline,2013 ACC/AHA Guideline, 2009 ACC/AHA Focused Update and 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in the Adult (DO NOT EDIT) [37] [38] [39] Self-Care Support in HF Dietary Sodium RestrictionManagement of Stage C HF : Activity, Exercise Prescription, and Cardiac RehabilitationBeta Blockers Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs) Sodium-Glucose Contransporter 2 Inhibitors Drugs of Unproven Value or That May Worsen HF GDMT Dosing: Sequencing and Uptitration Device and Interventional Therapies for HFrEF ICDs and CRTs

Class I

"3. In patients at least 40 days post-MI with LVEF ≤ 30% and NYHA class I symptoms while receiving GDMT, who have reasonable expectation of meaningful survival for > 1 year, ICD therapy is recommended for primary preve≤ntion of SCD to reduce total mortality . [200] (Level of Evidence: B-R ) "

"4. For patients who have LVEF ≤ 35%, sinus rhythm , LBBB with a QRS duration ≥150ms, and NYHA class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms on GDMT, CRT is indicated to reduce total mortality , reduce hospitalizations , and improve symptoms and QOL .[201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] (Level of Evidence: B-R ) "

Class IIa

"6. For patients who have LVEF ≤ 35%, sinus rhythm , a non-LBBB pattern with a QRS duration ≥ 150ms, and NYHA class II, III, or ambulatory class IV symptoms on GDMT, CRT can be useful to reduce total mortality , reduce hospitalizations , and improve symptoms and QOL . [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] [213] [214] [215] [216] [217] [218] (Level of Evidence: B-R ) "

"7. In patients with high-degree or complete heart block and LVEF of 36% to 50%, CRT is reasonable to reduce total mortality , reduce hospitalizations , and improve symptoms and QOL . [219] [220] (Level of Evidence: B-R ) "

"8. For patients who have LVEF ≤ 35%, sinus rhythm , LBBB with a QRS duration of 120 to 149 ms, and NYHA class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms on GDMT, CRT can be useful to reduce total mortality reduce hospitalizations , and improve symptoms and QOL . [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] [213] [214] [215] [216] [217] [218] (Level of Evidence: B-NR ) "

"9. In patients with AF and LVEF ≤ 35% on GDMT, CRT can be useful to reduce total mortality , improve symptoms and QOL , and increase LVEF , if: a) the patient requires ventricular pacing or otherwise meets CRT criteria and b) atrioventricular nodal ablation or pharmacological rate control will allow near 100% ventricular pacing with CRT. [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] [213] [214] [215] [216] [217] [218] (Level of Evidence: B-NR ) "

"10. For patients on GDMT who have LVEF ≤ 35% and are undergoing placement of a new or replacement device implantation with anticipated requirement for significant (>40%) ventricular pacing , CRT can be useful to reduce total mortality , reduce hospitalizations , and improve symptoms and QOL . [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] [213] [214] [215] [216] [217] [218] (Level of Evidence: B-NR ) "

"11. In patients with genetic arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy with high-risk features of sudden death , with EF ≤ 45%, implantation of ICD is reasonable to decrease sudden death. [221] [222] (Level of Evidence: B-NR ) "

Class IIb

"12. For patients who have LVEF ≤ 35%, sinus rhythm , a non-LBBB pattern with QRS duration of 120 to 149 ms, and NYHA class III or ambulatory class IV on GDMT, CRT may be considered to reduce total mortality , reduce hospitalizations , and improve symptoms and QOL . [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] [213] [214] [215] [216] [217] [218] (Level of Evidence: B-R ) "

"13. For patients who have LVEF ≤ 30%, ischemic case of HF , sinus rhythm , LBBB with a QRS duration ≥ 150ms, and NYHA class I symptoms on GDMT, CRT may be considered to reduce hospitalizations and improve symptoms and QOL . [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] [206] [213] [214] [215] [216] [217] [218] (Level of Evidence: B-R ) "

Related Chapters External Links References

↑ Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW (2009). "2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation" . Circulation 119 (14): e391–479. doi :10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065 . PMID 19324966 . Retrieved 2011-04-07 . ↑ McKelvie RS, Teo KK, McCartney N, Humen D, Montague T, Yusuf S (1995). "Effects of exercise training in patients with congestive heart failure: a critical review" . Journal of the American College of Cardiology 25 (3): 789–96. doi :10.1016/0735-1097(94)00428-S . PMID 7860930 . Retrieved 2011-04-07 . ↑ Packer M, Kessler PD, Lee WH (1987). "Calcium-channel blockade in the management of severe chronic congestive heart failure: a bridge too far". Circulation 75 (6 Pt 2): V56–64. PMID 3552317 . ↑ 4.0 4.1 Reed SD, Friedman JY, Velazquez EJ, Gnanasakthy A, Califf RM, Schulman KA (2004). "Multinational economic evaluation of valsartan in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT)" . American Heart Journal 148 (1): 122–8. doi :10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.040 . PMID 15215801 . Retrieved 2011-04-07 . ↑ Torp-Pedersen C, Møller M, Bloch-Thomsen PE, Køber L, Sandøe E, Egstrup K, Agner E, Carlsen J, Videbaek J, Marchant B, Camm AJ (1999). "Dofetilide in patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide Study Group" . The New England Journal of Medicine 341 (12): 857–65. doi :10.1056/NEJM199909163411201 . PMID 10486417 . Retrieved 2011-04-07 . ↑ Heerdink ER, Leufkens HG, Herings RM, Ottervanger JP, Stricker BH, Bakker A (1998). "NSAIDs associated with increased risk of congestive heart failure in elderly patients taking diuretics" . Archives of Internal Medicine 158 (10): 1108–12. PMID 9605782 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Gan SC, Barr J, Arieff AI, Pearl RG (1992). "Biguanide-associated lactic acidosis. Case report and review of the literature" . Archives of Internal Medicine 152 (11): 2333–6. PMID 1444694 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Masoudi FA, Inzucchi SE, Wang Y, Havranek EP, Foody JM, Krumholz HM (2005). "Thiazolidinediones, metformin, and outcomes in older patients with diabetes and heart failure: an observational study" . Circulation 111 (5): 583–90. doi :10.1161/01.CIR.0000154542.13412.B1 . PMID 15699279 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Swenson JR, Doucette S, Fergusson D (2006). "Adverse cardiovascular events in antidepressant trials involving high-risk patients: a systematic review of randomized trials". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 51 (14): 923–9. PMID 17249635 . ↑ Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB, Rosenfield KA, Sacks D, Stanley JC, Taylor LM, White CJ, White J, White RA, Antman EM, Smith SC, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B (2006). "ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation" . Circulation 113 (11): e463–654. doi :10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526 . PMID 16549646 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Storen EC, Tefferi A (2001). "Long-term use of anagrelide in young patients with essential thrombocythemia" . Blood 97 (4): 863–6. PMID 11159509 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ "Anagrelide, a therapy for thrombocythemic states: experience in 577 patients. Anagrelide Study Group". The American Journal of Medicine 92 (1): 69–76. 1992. PMID 1731512 . ↑ Lewis GD, Shah R, Shahzad K, Camuso JM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Hung J, Tawakol A, Gerszten RE, Systrom DM, Bloch KD, Semigran MJ (2007). "Sildenafil improves exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with systolic heart failure and secondary pulmonary hypertension" . Circulation 116 (14): 1555–62. doi :10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716373 . PMID 17785618 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, Baselga J, Norton L (2001). "Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2" . The New England Journal of Medicine 344 (11): 783–92. doi :10.1056/NEJM200103153441101 . PMID 11248153 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Chung ES, Packer M, Lo KH, Fasanmade AA, Willerson JT (2003). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure: results of the anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure (ATTACH) trial" . Circulation 107 (25): 3133–40. doi :10.1161/01.CIR.0000077913.60364.D2 . PMID 12796126 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ Yap YG, Camm AJ (2003). "Drug induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes" . Heart (British Cardiac Society) 89 (11): 1363–72. PMC 1767957 PMID 14594906 . Retrieved 2011-04-08 . ↑ 17.0 17.1 Packer M, Gottlieb SS, Kessler PD (1986). "Hormone-electrolyte interactions in the pathogenesis of lethal cardiac arrhythmias in patients with congestive heart failure. Basis of a new physiologic approach to control of arrhythmia". The American Journal of Medicine 80 (4A): 23–9. PMID 2871753 . ↑ Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM (1995). "A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure" . The New England Journal of Medicine 333 (18): 1190–5. doi :10.1056/NEJM199511023331806 . PMID 7565975 . Retrieved 2011-04-10 . ↑ Philbin EF (1999). "Comprehensive multidisciplinary programs for the management of patients with congestive heart failure". Journal of General Internal Medicine 14 (2): 130–5. PMID 10051785 . ↑ "Consensus recommendations for the management of chronic heart failure. On behalf of the membership of the advisory council to improve outcomes nationwide in heart failure". The American Journal of Cardiology 83 (2A): 1A–38A. 1999. PMID 10072251 . ↑ Brater DC (1998). "Diuretic therapy" . The New England Journal of Medicine 339 (6): 387–95. doi :10.1056/NEJM199808063390607 . PMID 9691107 . Retrieved 2011-04-12 . ↑ Cody RJ, Kubo SH, Pickworth KK (1994). "Diuretic treatment for the sodium retention of congestive heart failure" . Archives of Internal Medicine 154 (17): 1905–14. PMID 8074594 . Retrieved 2011-04-12 . ↑ 23.0 23.1 Patterson JH, Adams KF, Applefeld MM, Corder CN, Masse BR (1994). "Oral torsemide in patients with chronic congestive heart failure: effects on body weight, edema, and electrolyte excretion. Torsemide Investigators Group". Pharmacotherapy 14 (5): 514–21. PMID 7997385 . ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Richardson A, Bayliss J, Scriven AJ, Parameshwar J, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC (1987). "Double-blind comparison of captopril alone against frusemide plus amiloride in mild heart failure" . Lancet 2 (8561): 709–11. PMID 2888942 . Retrieved 2011-04-14 . ↑ Packer M, Medina N, Yushak M, Meller J (1983). "Hemodynamic patterns of response during long-term captopril therapy for severe chronic heart failure" . Circulation 68 (4): 803–12. PMID 6352079 . Retrieved 2011-04-14 . ↑ Risler T, Schwab A, Kramer B, Braun N, Erley C (1994). "Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of loop diuretics in renal failure". Cardiology PMID 7954539 . ↑ Cody RJ, Franklin KW, Laragh JH (1982). "Postural hypotension during tilt with chronic captopril and diuretic therapy of severe congestive heart failure". American Heart Journal 103 (4 Pt 1): 480–4. PMID 7039281 . ↑ Vasko MR, Cartwright DB, Knochel JP, Nixon JV, Brater DC (1985). "Furosemide absorption altered in decompensated congestive heart failure". Annals of Internal Medicine 102 (3): 314–8. PMID 3970471 . ↑ Dormans TP, van Meyel JJ, Gerlag PG, Tan Y, Russel FG, Smits P (1996). "Diuretic efficacy of high dose furosemide in severe heart failure: bolus injection versus continuous infusion" . Journal of the American College of Cardiology 28 (2): 376–82. doi :10.1016/0735-1097(96)00161-1 . PMID 8800113 . Retrieved 2011-04-14 . ↑ "Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. The SOLVD Investigattors" . The New England Journal of Medicine 327 (10): 685–91. 1992. doi :10.1056/NEJM199209033271003 . PMID 1463530 . Retrieved 2011-04-22 .↑ Exner DV, Dries DL, Domanski MJ, Cohn JN (2001). "Lesser response to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor therapy in black as compared with white patients with left ventricular dysfunction" . The New England Journal of Medicine 344 (18): 1351–7. doi :10.1056/NEJM200105033441802 . PMID 11333991 . Retrieved 2011-04-22 . ↑ 32.0 32.1 Carson P, Ziesche S, Johnson G, Cohn JN (1999). "Racial differences in response to therapy for heart failure: analysis of the vasodilator-heart failure trials. Vasodilator-Heart Failure Trial Study Group" . Journal of Cardiac Failure 5 (3): 178–87. PMID 10496190 . Retrieved 2011-04-22 . ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Garg R, Yusuf S (1995). "Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials". JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association 273 (18): 1450–6. PMID 7654275 . ↑ 34.0 34.1 Packer M, Poole-Wilson PA, Armstrong PW, Cleland JG, Horowitz JD, Massie BM, Rydén L, Thygesen K, Uretsky BF (1999). "Comparative effects of low and high doses of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril, on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure. ATLAS Study Group" . Circulation 100 (23): 2312–8. PMID 10587334 . Retrieved 2011-04-22 . ↑ Delahaye F, de Gevigney G (2000). "Is the optimal dose of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with congestive heart failure definitely established?" . Journal of the American College of Cardiology 36 (7): 2096–7. PMID 11127446 . Retrieved 2011-04-22 . ↑ "Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy--I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration" . BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 308 (6921): 81–106. 1994. PMC 2539220 PMID 8298418 . Retrieved 2011-04-22 .↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM; et al. (2022). "2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines" . Circulation . 145 (18): e876–e894. doi :10.1161/CIR.0000000000001062 . PMID 35363500 . ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Masoudi FA, Butler J, McBride PE; et al. (2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines" . J Am Coll Cardiol . doi :10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019 . PMID 23747642 . ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG et al. (2009) 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation 119 (14):1977-2016.DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064 PMID: 19324967