Chronic hypertension medical therapy

|

Hypertension Main page |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Lakshmi Gopalakrishnan, M.B.B.S. [2]; Assistant Editor-In-Chief: Taylor Palmieri

Overview

There are many classes of medications for treating hypertension, together called antihypertensives, which by varying means act by lowering blood pressure. Evidence suggests that reduction of the blood pressure by 5-6 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 40%, of coronary heart disease by 15-20%, and reduces the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from vascular disease.

Medical Therapy

Goals of Therapy

In addition to alleviating symptoms of hypertension, such as headache and blurry vision, the ultimate long term goals of the management of hypertension are to reduce cardiovascular risk, prevent cardiovascular events, and reverse or ameliorate target organ damage. According to “Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration” in 2000, lowering blood pressure decreases the incidence of stroke by an average of 30%, MI by an average of 20%, major cardiovascular events by an average of 21%, and heart failure by an average of more than 50%.[1]

JNC 7 has established the goal blood pressure to be < 140/90 mmHg[2], with major focus on reduction of systolic blood pressure due to its role in the consequential reduction of diastolic blood pressure. In special populations such as those with diabetes mellitus or renal disease, the blood pressure goal is < 130/80 mmHg.[3][4]

Approach to Medical Therapy

Pharmacologic therapy is normally initiated based on the cardiovascular risk. Failure to achieve BP goals in patients with low and moderate cardiovascular risk after three to six months of non-pharmacologic measures necessitates the initiation of pharmacologic therapy. Usually, anti-hypertensive therapy begins when BP > 140/90 mmHg in the general population. Special cases include diabetic patients who have been shown to benefit from a lower diastolic blood pressure threshold in the HOT[5] and the UKPDS[6] trials and would require therapy when BP > 140/80 mmHg.[7] Another important population benefiting from lower BP goals are patients with chronic kidney disease in which treatment should be initiated when BP > 130/80 mmHg.[8]

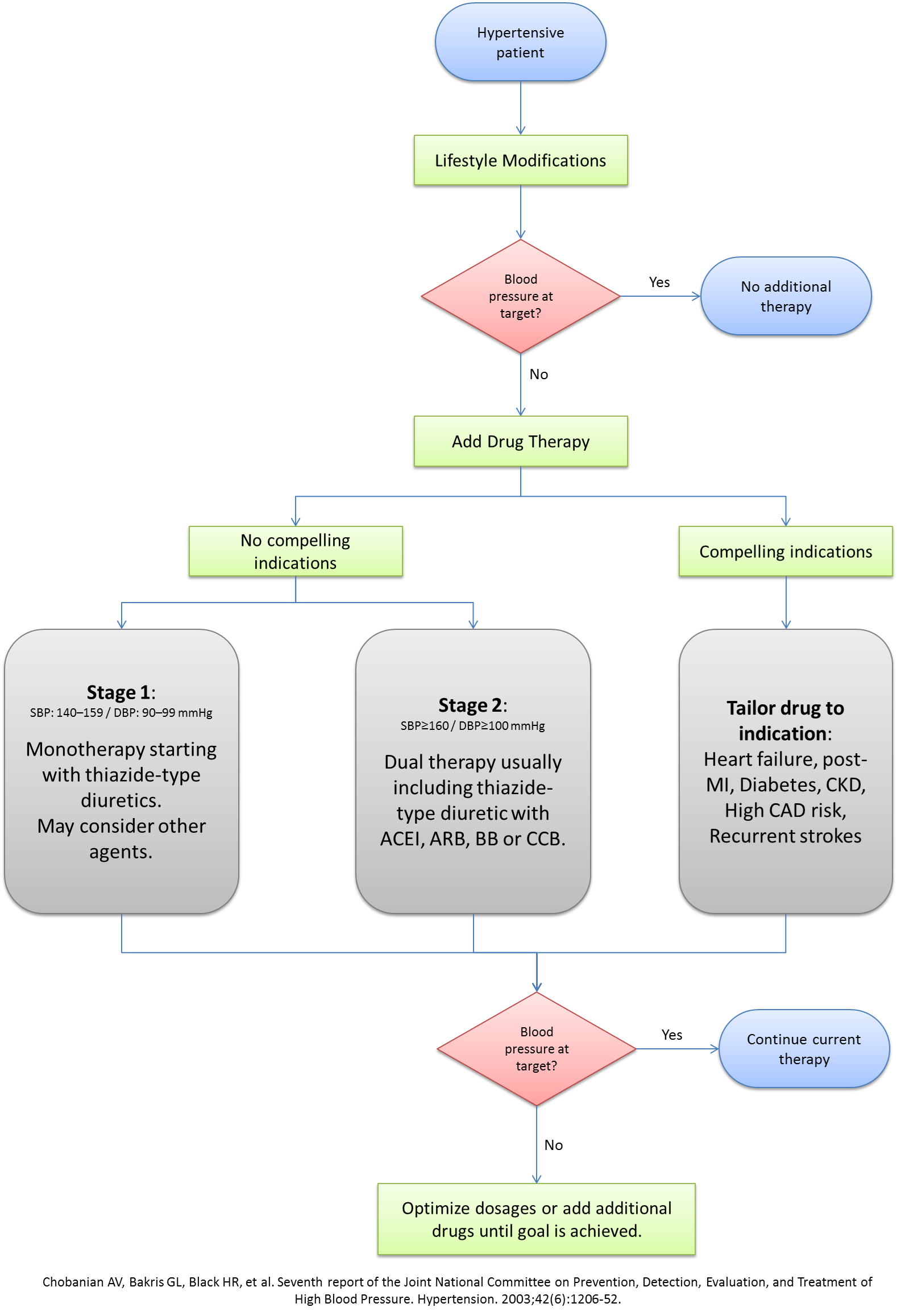

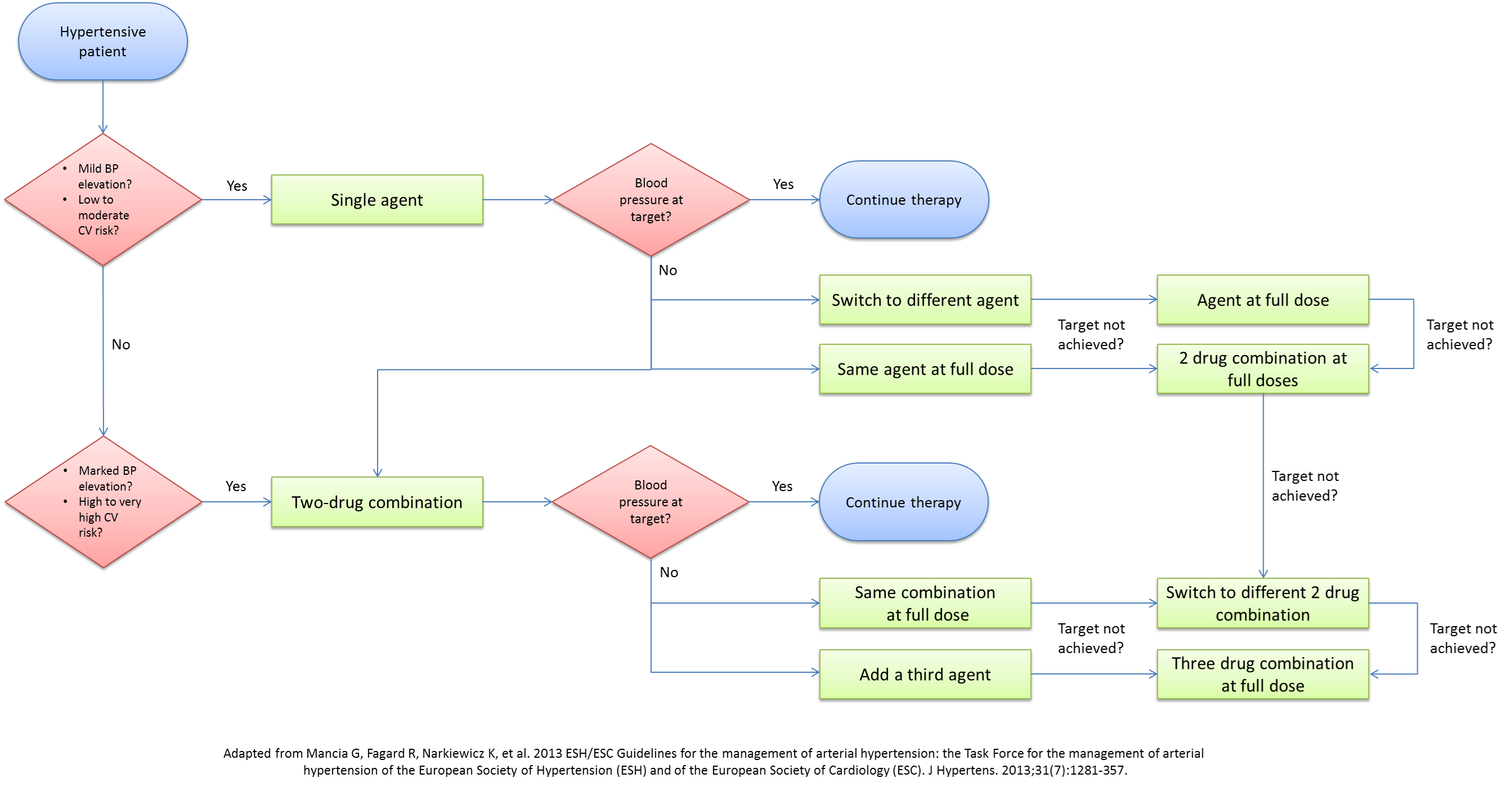

A lot of debate exists on the optimal approach to the medical management of hypertension. With the multitude of classes and agents that can be used, several questions arise about the single best agent, the optimal combination of agents, and the best step-wise approach to medical management. Although JNC7 tried to address these issues, almost a decade has passed since the release of their recommendations, with a myriad of studies and trials presenting newer compelling evidence to update the current recommendations. The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of hypertension have dwelled into these issues and have outlined the rationale behind adopting a new approach. Below are the algorithms for the approach to the medical therapy of hypertension presented by JNC7 in 2004 and ESH/ESC in 2013.

Common Antihypertensive Agents

Management of Hypertension in Special Populations

Ethnic groups

- African Americans: Enforcement of DASH diet due to its association with greater reduction of BP than other ethnicities (Ref: 11136953). According to the ALLHAT trial that included 15,000 Blacks, diuretics were more effective for African Americans than other classes of anti-hypertensive agents.[9]

- Mexican Americans, other Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Asian/Pacific Islanders have been recruited in insufficient numbers in research trials to adequately identify special considerations.[10]

Diabetes Mellitus

- According to the American Diabetes Association, BP goal for diabetic patients must be < 140/80 mmHg to reduce the progression of target organ damage but that lower systolic blood pressure targets <130 mmHg can be targeted in younger patients.[7] The recent shift in the approach to hypertension in diabetics proposed by the 2013 ADA guidelines as well as the 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines is supported by the fact that no major trials have consistently achieved a blood pressure level below 130/80 mmHg in diabetics nor have the smaller trials shown any major benefit from intensive treatment to reach that threshold. In parallel to the ADA, the 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines only support a lower DBP goal set at 80-85 mmHg.[11]

- According to the American Diabetes Association, ACEI and ARBs are considered superior agents in diabetic patients for their renal protective effects (delay in both GFR decrease and albuminuria worsening).[12] Although RAAS blockers such as ACEI and ARBs are beneficial their combination can sometimes have significant effects on renal function especially in high risk patients.[13]

- Thiazide-type diuretics were shown to be beneficial in reducing heart disease in diabetic patients.[9] Despite their side effects of worsening hyperglycemia, thiazide-type diuretics were associated with stable target organ damage compared to other anti-hypertensive agents.[14]

- According to the LIFE study, beta-blockers are especially beneficial in diabetic patients with ischemic heart disease despite their controversial role as monotherapy.[15] Even though decreased insulin sensitivity is a side effect, beta-blockers are not absolutely contraindicated in diabetes.[10]

- In the management of hypertension, CCBs are unquestionably useful in the reduction of BP values. However, their role in preventing target organ damage in diabetic patients is inferior to other agents. The ALLHAT study demonstrated that amlodipine, a DHP CCB, was less effective than thiazides in reducing heart failure.[9] Similarly, the ABCD Trial also showed that nisoldipine, a dihydropyridine CCB was less effective than enalapril, an ACEI, in reducing ischemic heart disease.[16]

Metabolic Syndrome

- Metabolic syndrome as a clinical concept is largely debatable, mostly since studies have shown little added benefit of the definition on the predictive power of each of the constitutive individual factors, making recommendations about hypertension treatment in this subpopulation limited.[11]

- Lifestyle modification plays the most important role in anti-hypertensive therapy in patients with metabolic syndrome.

- Persistence of high BP > 140/90 mmHg still warrants pharmacologic therapy.

- Management of dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, and other concomitant comorbidities is essential for reduction of BP in patients with metabolic syndrome.[10]

Elderly

- There is particular advantage in weight loss and reduced sodium intake in elderly subjects. Trial of Non-pharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE) showed that sodium intake of less than 80 mmol per day (2 g of sodium per day or 5 grams of sodium chloride salt) could allow the discontinuation of anti-hypertensive agents in 40% of elderly.[17]

- The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines modified the approach adopted in 2007 to treat hypertension regardless of age. The new guidelines advocate holding medical therapy for elderly patients with stage 1 hypertension and initiating treatment only in those with stage 2 hypertension or greater. It is also recommended to target a SBP below 150 mmHg rather than 140mmHg. This rationale follows several studies involving elderly patients not achieving blood pressure measurements below 140mmHg. In patients below 80 years of age, treatment can be targeted below 140 mmHg if goal can be tolerated.[11]

- The HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) showed that in patients older than 80 years-old with SBP >160mmHg, a significant reduction in major CV events and all-cause mortality can be seen by aiming at SBP values <150mmHg. [18]

- The JNC7 guidelines concluded in 2004 that antihypertensive therapy should not be withheld in patients with stage 1 hypertension based on age, even though no RCTs had shown benefits from treatment in this population at the time.

Pregnant Women

- Distinguishing gestational from pre-gestational hypertension in pregnant women is essential. Hypertension is not considered to be caused by pregnancy when it develops before 20 weeks of gestation.[10]

- Hypertensive women who plan to become pregnant should be instructed to use safe anti-hypertensive medications, such as methyldopa preferentially because long-term follow up studies are available. [19] Labetolol and nifedipine are also other treatment options that can be considered in pregnancy.[11]

- Pregnant women with stage 1 hypertension present with low cardiovascular risk and anticipated physiological lowering of blood pressure during pregnancy. Thus healthcare providers might advise mere lifestyle modification as therapy during pregnancy and breast feeding, with caution on excessive weight reduction and with possible restriction of aerobic physical activity.[10]

- The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines recommend drug treatment of severe hypertension in pregnancy defined as SBP >160 mmHg or DBP >110 mmHg. They also advocate considering treatment in pregnant women with persistant hypertension ≥150/95 mmHg and in symptomatic patients or patients with target organ damage with BP ≥140/90 mmHg.[11]

Hypertensive Emergency & Urgency

- Hypertensive emergency is defined as high blood pressure causing acute target organ damage. Usually BP exceed 180/20 mmHg, but can sometimes occur at even lower values in patients who do not usually have high blood pressure.

- Hypertensive urgency is defined as a BP > 180/120 mmHg without target organ damage. Hypertensive urgency may or may not be symptomatic.

- Triage to differentiate between hypertensive emergency and urgency is crucial for appropriate management. While hypertensive emergencies require intensive care unit (ICU) admission for close monitoring and aggressive parenteral agents, hypertensive urgencies can be managed in the emergency department with outpatient follow-up for optimization of therapy.[10]

- Treatment is based on titrated intravenous medications that act rapidly but safely especially in avoiding severe hypotension and ischemic organ damage. Nicardipine, sodium nitroprusside, labetalol, furosemide and nitrates are some of the agents used. In certain cases of volume overload-associated hypertensive emergency where diuresis is insufficient, dialysis and ultrafiltration may be of benefit.[11]

- Generally, JNC 7 outlines the acute management of hypertensive emergencies as reduction of a maximum of 25% of mean arterial BP within the first hour followed by decrease of BP to 160/100 within the next 2 to 6 hours. Normalization of blood pressure should occur at a span of 24-48 hours. Rapid decrease in BP might precipitate ischemia caused by target organ damage.[10]

- The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines do not dwell much into the treatment of hypertensive emergencies due to the lack of evidence considering the small number of cases but recommend that treatment be individualized by the physician.[11]

- Specific clinical situations are considered exceptions to the abovementioned management plan:[10]

- Ischemic stroke will not require immediate BP lowering to maintain cerebral perfusion.

- Aortic dissection requires SBP to be lowered immediately to < 100 mmHg if tolerated followed by rapid specific management.

References

- ↑ Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N, Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration (2000). "Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration". Lancet. 356 (9246): 1955–64. PMID 11130523.

- ↑ Maldonado J (1998). "[Recommended article of the month: Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the hypertension optimal treatment (HOT) randomised trial]". Rev Port Cardiol. 17 (10): 843–4. PMID 9865094.

- ↑ Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P, American Diabetes Association (2003). "Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes". Diabetes Care. 26 Suppl 1: S80–2. PMID 12502624.

- ↑ National Kidney Foundation (2002). "K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification". Am J Kidney Dis. 39 (2 Suppl 1): S1–266. PMID 11904577.

- ↑ Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlöf B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S; et al. (1998). "Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group". Lancet. 351 (9118): 1755–62. PMID 9635947 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ "Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group". BMJ. 317 (7160): 703–13. 1998. PMC 28659. PMID 9732337 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Summary of revisions for the 2013 clinical practice recommendations". Diabetes Care. 36 Suppl 1: S3. 2013. doi:10.2337/dc13-S003. PMC 3537268. PMID 23264423.

- ↑ Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL; et al. (2003). "Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure". Hypertension. 42 (6): 1206–52. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. PMID 14656957 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Rodeheffer RJ (2011). "Hypertension and heart failure: the ALLHAT imperative". Circulation. 124 (17): 1803–5. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.059303. PMID 22025634.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Cuddy ML (2005). "Treatment of hypertension: guidelines from JNC 7 (the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure 1)". J Pract Nurs. 55 (4): 17–21, quiz 22-3. PMID 16512265.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M; et al. (2013). "2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". J Hypertens. 31 (7): 1281–357. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc. PMID 23817082.

- ↑ "Executive summary: Standards of medical care in diabetes--2013". Diabetes Care. 36 Suppl 1: S4–10. 2013. doi:10.2337/dc13-S004. PMC 3537272. PMID 23264424.

- ↑ ONTARGET Investigators. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I; et al. (2008). "Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events". N Engl J Med. 358 (15): 1547–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. PMID 18378520. Review in: J Fam Pract. 2009 Jan;58(1):24-7 Review in: Evid Based Med. 2008 Oct;13(5):147

- ↑ Weinberger MH (1985). "Blood pressure and metabolic responses to hydrochlorothiazide, captopril, and the combination in black and white mild-to-moderate hypertensive patients". J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 7 Suppl 1: S52–5. PMID 2580177.

- ↑ Sica DA (2002). "Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol". Curr Hypertens Rep. 4 (4): 321–3. PMID 12117460.

- ↑ Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Esler A, Mehler P (2002). "Effects of aggressive blood pressure control in normotensive type 2 diabetic patients on albuminuria, retinopathy and strokes". Kidney Int. 61 (3): 1086–97. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00213.x. PMID 11849464.

- ↑ Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Easter L, Wilson AC, Folmar S, Lacy CR (2001). "Effects of reduced sodium intake on hypertension control in older individuals: results from the Trial of Nonpharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE)". Arch Intern Med. 161 (5): 685–93. PMID 11231700.

- ↑ Bulpitt CJ, Beckett NS, Peters R, Leonetti G, Gergova V, Fagard R; et al. (2012). "Blood pressure control in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)". J Hum Hypertens. 26 (3): 157–63. doi:10.1038/jhh.2011.10. PMID 21390056.

- ↑ ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics (2002). "ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002". Obstet Gynecol. 99 (1): 159–67. PMID 16175681.

- Pages with reference errors

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 errors: PMID

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: PMC format

- Aging-associated diseases

- Cardiology

- Emergency medicine

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Medical conditions related to obesity

- Nephrology

- Up-To-Date

- Up-To-Date cardiology

- Cardiology board review