Aortic stenosis

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

|

WikiDoc Resources for Aortic stenosis |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Aortic stenosis Most cited articles on Aortic stenosis |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Aortic stenosis |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Aortic stenosis at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Aortic stenosis Clinical Trials on Aortic stenosis at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Aortic stenosis NICE Guidance on Aortic stenosis

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Aortic stenosis Discussion groups on Aortic stenosis Patient Handouts on Aortic stenosis Directions to Hospitals Treating Aortic stenosis Risk calculators and risk factors for Aortic stenosis

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Aortic stenosis |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Aortic stenosis further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editors-In-Chief: Claudia P. Hochberg, M.D. [2]; Abdul-Rahman Arabi, M.D. [3]; Keri Shafer, M.D. [4]

Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [5] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

The aortic valve controls the direction of blood flow from the left ventricle to the aorta. When in good working order, the aortic valve does not impede the flow of blood between these two spaces. Under some circumstances, the aortic valve becomes narrower than normal, impeding the flow of blood. This is known as aortic valve stenosis, or aortic stenosis, often abbreviated as AS.

Prevalence

Aortic stenosis is a common problem. Approximately 2% of people over the age of 65, 3% of people over age 75, and 4% percent of people over age 85 have the disorder. In North America and Europe, at least, the population is aging. Hence, the prevalence of aortic stenosis is increasing. Since the disease carries with it considerable morbidity and mortality, both with large personal and economic impact, aortic stenosis is a major health problem.

Etiology

The etiology of Left-Sided Outflow Obstruction can be divided into two broad categories:

- Acquired Aortic Stenosis and

- Congenital Left-Sided Outflow Obstruction

Major causes and predisposing conditions of aortic stenosis include acute rheumatic fever and bicuspid aortic valve. As individuals age, calcification of the aortic valve may occur and result in stenosis. This is especially likely to occur in people with a bicuspid aortic valve, but also occurs in the setting of perfectly normal valves as a result of age-induced 'wear and tear'. Typically, aortic stenosis due to calcification of a bicuspid valve occurs in the 4th of 5th decade of life, whereas that due to calcification of a normal valve tends to occur later - around the 7th or 8th decade.

Of the various forms of aortic stenosis, the calcific type is predominant. Since calcific aortic stenosis shares many pathological features and risk factors with atherosclerosis, and since atherosclerosis may be prevented and/or reversed by cholesterol lowering, there has been interest in attempting to modify the course of calcific aortic stenosis by cholesterol lowering with statin drugs. Although a number of small, observational studies demonstrated an association between lowered cholesterol and decreased progression, and even regression, of calcific aortic stenosis, a recent, large randomized clinical trial, published in 2005, failed to find any predictable effect of cholesterol lowering on calcific aortic stenosis. However, a 2007 study did demonstrate a slowing of aortic stenosis with the statin rosuvastatin.[1]

Genetics

Congenital bicuspid valve is the most frequent form of congenital heart disease affecting approximately 1-2% of the population. 1/3rd of Supravalvular Aortic Stenosis cases are transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait as 60% of patients with supravalvular obstruction have Williams syndrome (supravalvular obstruction, intellectual impairment and facial abnormalities).

Pathophysiology

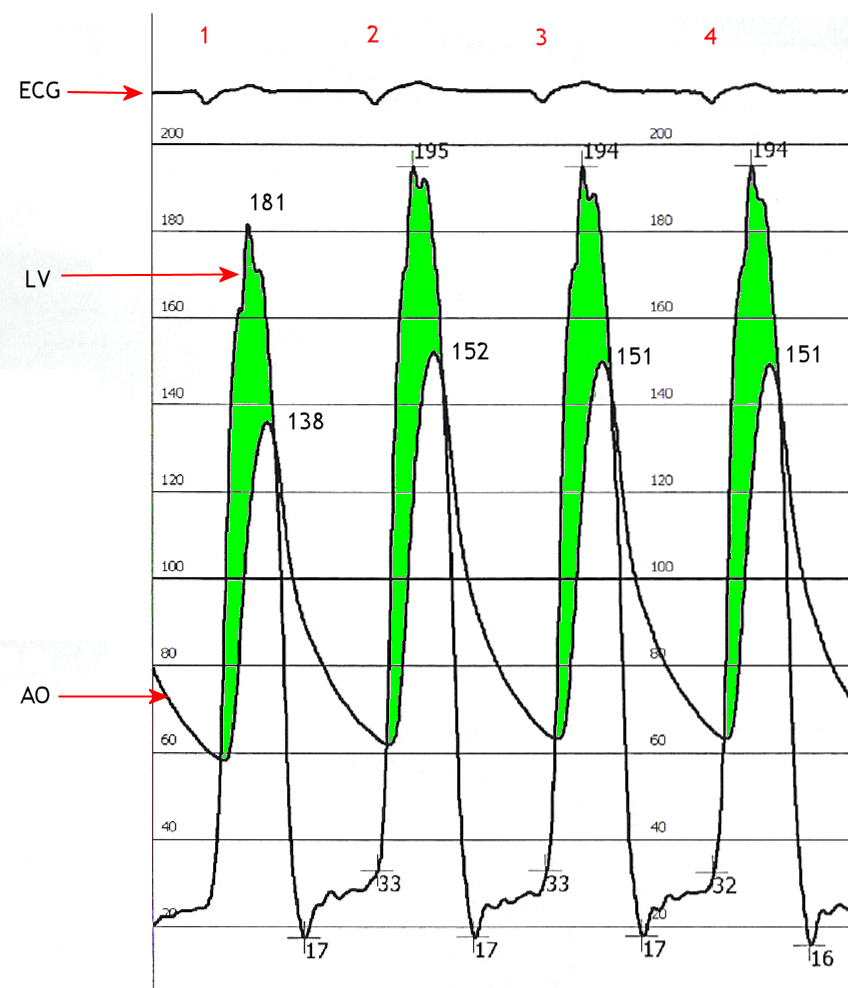

When the aortic valve becomes stenotic, it causes a pressure gradient between the left ventricle (LV) and the aorta.[2] The more constricted the valve, the higher the gradient between the LV and the aorta. For instance, with a mild AS, the gradient may be 20 mmHg. This means that, at peak systole, while the LV may generate a pressure of 140 mmHg, the pressure that is transmitted to the aorta will only be 120 mmHg. So, while a blood pressure cuff may measure a normal systolic blood pressure, the actual pressure generated by the LV would be considerably higher.

In individuals with AS, the left ventricle (LV) has to generate an increased pressure in order to overcome the increased afterload caused by the stenotic aortic valve and eject blood out of the LV. The more severe the aortic stenosis, the higher the gradient is between the left ventricular systolic pressures and the aortic systolic pressures. Due to the increased pressures generated by the left ventricle, the myocardium (muscle) of the LV undergoes hypertrophy (increase in muscle mass). This is seen as thickening of the walls of the LV. The type of hypertrophy most commonly seen in AS is concentric hypertrophy, meaning that all the walls of the LV are (approximately) equally thickened.

Differential diagnosis

- Fixed subvalvular obstruction

- Presence of subaortic membrane

- May be difficult to visualise in 2D echocardiography

- Presents in early adulthood

- Valve is not stenotic, but doppler shows increased gradient.

- Can be diagnosed with careful search using pulse wave doppler and colour flow mapping

- Dynamic subaortic obstruction

- Occurs with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy(HOCM)

- Other features of HCM

- late peaking, triangular CW doppler

- changes with provocative measures

General Classifications

Acquired Aortic Stenosis

Adult acquired aortic stenosis has two major causes, namely calcific disease of a structurally normal trileaflet valve or Rheumatic valve disease. Calcific aortic disease has many of the same risk factors as atherosclerotic disease and is characterized by fat deposition, inflammation, and calcification. it is also frequently seen in patients with renal failure. In comparison, Rheumatic valve disease involves fusion of the commissures between the leaflets, with a small central orifice.

Congenital Left-Sided Outflow Obstruction

Congenital Left-Sided Outflow Obstruction can be due to a variety of conditions, all of which culminate in obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. These conditions include:

- Malformation of the aortic valve such as a bicuspid aortic valve

- Unicuspid valve

- Hypoplasia of the annulus

- Supravalvular stenosis

- Subvalvular stenosis

General Symptoms of Aortic Stenosis

When symptomatic, aortic stenosis can cause dizziness, syncope, angina and congestive heart failure. More symptoms indicate a worse prognosis. Treatment requires replacement of the diseased valve with an artificial heart valve.

Congestive Heart Failure

Congestive heart failure (CHF) carries a grave prognosis in patients with AS. Patients with CHF that is attributed to AS have a 2 year mortality rate of 50%, if the aortic valve is not replaced.

CHF in the setting of AS is due to a combination of systolic dysfunction (a decrease in the ejection fraction) and diastolic dysfunction (elevated filling pressure of the LV).

Syncope

Syncope in the setting of heart failure increases the risk of death. In patients with syncope, the 3 year mortality rate is 50%, if the aortic valve is not replaced.

It is unclear why aortic stenosis causes syncope. One popular theory is that severe AS produces a nearly fixed cardiac output. When the patient exercises, their peripheral vascular resistance will decrease as the blood vesels of the skeletal muscles dilate to allow the muscles to receive more blood to allow them to do more work. This decrease in peripheral vascular resistance is normally compensated for by an increase in the cardiac output. Since patients with severe AS cannot increase their cardiac output, the blood pressure falls and the patient will syncopize due to decreased blood perfusion to the brain.

A second theory as to why syncope may occur in AS is that during exercise, the high pressures generated in the hypertrophied LV cause a vasodepressor response, which causes a secondary peripheral vasodilation which in turn causes decreased blood flow to the brain. Indeed, in aortic stenosis, because of the fixed obstruction to bloodflow out from the heart, it may be impossible for the heart to increase its output to offset peripheral vasodilation.

A third mechanism may sometimes be operative. Due to the hypertrophy of the left ventricle in aortic stenosis, including the consequent inability of the coronary arteries to adequately supply blood to the myocardium (see "Angina" below), arrhythmias may develop. These can lead to syncope.

Finally, in calcific aortic stenosis at least, the calcification in and around the aortic valve can progress and extend to involve the electrical conduction system of the heart. If that occurs, the result may be heart block - a potentially lethal condition of which syncope may be a symptom.

Angina

Angina in the setting of heart failure also increases the risk of death. In patients with angina, the 5 year mortality rate is 50%, if the aortic valve is not replaced.

Angina in the setting of AS is secondary to the left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) that is caused by the constant production of increased pressure required to overcome the pressure gradient caused by the AS. While the myocardium (i.e. heart muscle) of the LV gets thicker, the arteries that supply the muscle do not get significantly longer or bigger, so the muscle may become ischemic (i.e. doesn't receive an adequate blood supply). The ischemia may first be evident during exercise, when the heart muscle requires increased blood supply to compensate for the increased workload. The individual may complain of exertional angina. At this stage, a stress test with imaging may be suggestive of ischemia.

Eventually, however, the muscle will require more blood supply at rest than can be supplied by the coronary artery branches. At this point there may be signs of ventricular strain pattern on the EKG, suggesting subendocardial ischemia. The subendocardium is the region that becomes ischemic because it is the most distant from the epicardial coronary arteries.

Associated Symptoms

In Heyde's syndrome, aortic stenosis is associated with angiodysplasia of the colon. Recent research has shown that the stenosis causes a form of von Willebrand disease by breaking down its associated coagulation factor (factor VIII-associated antigen, also called von Willebrand factor), due to increased turbulence around the stenosed valve.

Physical Examination

The critically ill patient may be in extremis. Peripheral edema may be present in the patient with CHF. Pulmonary rales may be present in the patient with CHF.

Aortic stenosis is most often diagnosed when it is asymptomatic and can sometimes be detected during routine examination of the heart and circulatory system. Good evidence exists to demonstrate that certain characteristics of the peripheral pulse can rule in the diagnosis.[3] In particular, there may be a slow and/or sustained upstroke of the arterial pulse, and the pulse may be of low volume. This is sometimes referred to as pulsus tardus et parvus. There may also be a noticeable delay between the first heart sound (on auscultation) and the corresponding pulse in the carotid artery (so-called 'apical-carotid delay'). Similarly, there may be a delay between the appearance of each pulse in the brachial artery (in the arm) and the radial artery (in the wrist).

An easily heard systolic, crescendo-decrescendo (i.e. 'ejection') murmur is heard loudest at the upper right sternal border, and radiates to the carotid arteries bilaterally. The murmur increases with squatting, decreases with standing and isometric muscular contraction, which helps distinguish it from hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). The murmur is louder during expiration, but is also easily heard during inspiration. The more severe the degree of the stenosis, the later the peak occurs in the crescendo-decrescendo of the murmur.

The 2nd heart sound tends to become softer as the aortic stenosis becomes more severe. This is a result of the increasing calcification of the valve preventing it from "snapping" shut and producing a sharp, loud sound. Due to increases in left ventricular pressure from the stenotic aortic valve, over time the ventricle may hypertrophy, resulting in a diastolic dysfunction. As a result, one may hear a 4th heart sound due to the stiff ventricle. With continued increases in ventricular pressure, dilatation of the ventricle will occur, and a 3rd heart sound may be manifest.

Finally, aortic stenosis often co-exists with some degree of aortic insufficiency. Hence, the physical exam in aortic stenosis may also reveal signs of the latter, for example an early diastolic decrescendo murmur. Indeed, when both valve abnormalities are present, the expected findings of either may be modified or may not even be present. Rather, new signs emerge which reflect the presence of simultaneous aortic stenosis and insufficiency, e.g. pulsus bisferiens.

According to a meta analysis, the most useful findings for ruling in aortic stenosis in the clinical setting were slow rate of rise of the carotid pulse(positive likelihood ratio ranged 2.8-130 across studies), mid to late peak intensity of the murmur(positive likelihood ratio, 8.0-101), and decreased intensity of the second heart sound(positive likelihood ratio, 3.1-50).[4]

Peripheral Signs Include

- a slow-rising, small volume carotid pulse

- narrowed pulse pressure

- sustained, thrusting apex beat which is usually not displaced unless the stenosis is severe

Diagnostic tests

The electrocardiogram (ECG)

Although aortic stenosis does not lead to any specific findings on the ECG, it still often leads to a number of electrocardiographic abnormalities. ECG manifestations of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) are common in aortic stenosis and arise as a result of the stenosis having placed a chronically high pressure load on the left ventricle (with LVH being the expected response to chronic pressure loads on the left ventricle no matter how caused).

As noted below, the calcification process which occurs in aortic stenosis can progress to extend beyond the aortic valve and into the electrical conduction system of the heart. Evidence of this phenomenon may include heart block that is apparent on the ECG but otherwise undetectable.

Chest X Ray

Chest xray can show dilatation of the ascending aorta or an enlarged left ventricle of there is severe aortic regurgitation.

Echocardiogram

Echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) is the best non-invasive test to evaluate the aortic valve anatomy and function.

The aortic valve area can be calculated non-invasively using echocardiographic flow velocities. Using the velocity of the blood through the valve, the pressure gradient across can be calculated by the equation:

Gradient = 4(velocity)² mmHg

A normal aortic valve has no gradient. If the mean gradient is <25 mm Hg, the stenosis is mild; if the mean gradient is between 25 mm Hg and 50 mm Hg, the stenosis is moderate; if the mean gradient is >50 mm Hg the stenosis is severe; and when the gradient is greater than 70 mm Hg, the stenosis is critical. A normal aortic valve area is >2 cm2. If the valve area is between 1.3 and 2.0 cm2, the stenosis is mild; if the valve area is between 1.0 and 1.3 cm2, the stenosis is moderate; if the valve area is between 0.7 and 1.0 cm2, the stenosis is moderate-severe; areas of less than 0.7 cm2 constitute severe aortic stenosis.

2D echocardiography of the aortic valve in the parasternal long axis view demonstrates right and non coronary leaflets. In the parasternal short axis view, leaflets open equally and forms a circular orifice during systole. During diastole, the normal leaflets form a three pointed star with prominence at the closing point. (nodules of Arentius)

|

Severity summary

| Severity | mild | moderate | severe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valve area | 2.0 - 1.5 | 1- 1.5 | <1 |

| peak velocity (m/s) | 2 -3 | 3-4 | >4 |

| Peak gradient (mmHg) | <35 | 35-65 | >65 |

| Mean gradient (mmHg) | <20 | 20-40 | >40 |

- Calcific Aortic Stenosis

<googlevideo>-7545394293366400735&hl=en</googlevideo>

MRI and CT

Cardiovascular MRI (CMR) is a useful tool in diagnosis and evaluation of bicuspid aortic valve. Stead-state free precession sequences are used to obtain a slice in the place of the valve, and show the anatomy of the valve well. Differentiation may be made between an anatomically bicuspid valve, and anatomically trileaflet valve with fused comissures ("functionally-bicuspid valve"). In addition, CMR is invaluable in defining anatomic valve area, in quantification of aortic regurgitation, and in diagnosis of concomitant cardiovascular abnormalities, such as thoracic aortic dilatation/aneurysm and mitral valve abnormalities.

Heart catheterization

The heart may be catheterized to directly measure the pressure on both sides of the aortic valve. The pressure gradient may be used as a decision point for treatment. Catheterization is accurate for moderate velocity stenosis, while Doppler echo is more accurate at faster velocities.

Precautions

People with aortic stenosis of any aetiology are at risk for the development of infection of their stenosed valve, i.e. infective endocarditis. To lessen the chance of developing that serious complication, people with AS are usually advised to take antibiotic prophylaxis around the time of certain dental/medical/surgical procedures. Such procedures may include dental extraction, deep scaling of the teeth, gum surgery, dental implants, treatment of esophageal varices, dilation of esophageal strictures, gastrointestinal surgery where the intestinal mucosa will be disrupted, prostate surgery, urethral stricture dilation, and cystoscopy. Note that routine upper and lower GI endoscopy (i.e. gastroscopy and colonoscopy), with or without biopsy, are not usually considered indications for antibiotic prophylaxis.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the American Heart Association has recently changed its recommendations regarding antibiotic prophylaxis for endocarditis. Specifically, as of 2007, it is recommended that such prophylaxis be limited only to 1. those with prosthetic heart valves, 2. those with previous episode(s) of endocarditis, and 3. those with certain types of congenital heart disease.[5]

Since the stenosed aortic valve may limit the heart's output, people with aortic stenosis are at risk of syncope and dangerously low blood pressure should they use any of a number of common medications. Ironically, these same medicines are used to treat a variety of cardiovascular diseases, many of which may co-exist with aortic stenosis. Examples include nitroglycerin, nitrates, ACE inhibitors, terazosin (Hytrin), and hydralazine. Note that all of these substances lead to peripheral vasodilation. Normally, however, in the absence of aortic stenosis, the heart is able to increase its output and thereby offset the effect of the dilated blood vessels. In some cases of aortic stenosis, however, due to the obstruction of blood flow out of the heart caused by the stenosed aortic valve, cardiac output cannot be increased. Low blood pressure or syncope may ensue.

Bicuspid Aortic Stenosis

Epidemiology

The most common congenital abnormality of the heart is the bicuspid aortic valve. Approximately 1-2% of the population have bicuspid aortic valves, and the majority will cause no problems. It can be manifested as a murmur. In this condition, instead of three cusps, the aortic valve has two cusps which results from the fusing of one of the commissures.

This condition is often undiagnosed until later in life when the person develops symptomatic aortic stenosis. Aortic stenosis occurs in this condition usually in patients in their 40s or 50s, an average of 10 years earlier than can occur in people with congenitally normal aortic valves. 30% of cases are diagnosed in adolescence.

The congenital bicuspid aortic valve may become calcified, which may lead to half the cases of surgically important pure aortic stenosis in adults, with varying degrees of severity of aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation.

Congenital aortic stenosis accounts for 5% of congenital heart defects, is the most common congenital anomaly and is more common in men than women (3:1 to 5:1).

Anatomy

In 1513, Leonardo da Vinci was the first artist who first sketched the bicuspid aortic valve as cuspal inquelity.

The Bicuspid Aortic Valve has two cusps: one larger than the other. It is considered unobstructive if the edges of the cusps are free. If the edges are fused or no free the aortic valve is considered obstructive developing a dome during systole.

There are five varieties of congenitally abnormal aortic valves based on the number and types of cusps and commisures:

- Unicuspid:

- Acommissural

- Unicommissural

- Bicuspid

- Tricuspid:

- Miniature (small aortic ring)

- Dysplastic

- Cuspal inequality

- Quadricuspid

- Six-cuspid

Pathophysiology and Natural History

A congenital bicuspid aortic valve may be associated with the development of either progressive clacific stenosis or regurgitation. The defect is the leading cause of acquired calcified aortic stenosis (see above section on acquired aortic stenosis).

Clinical Features

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms may not develop until adolescence (in later adulthood with acquired AS) and include DOE, exertional dizziness or syncope, exertional angina and heart failure. Occassionally patients with aortic stenosis may present with fever and bacteremia as these patients are highly susceptible to bacterial endocarditis. Lastly, patients with congenital bicuspid aortic valves may present with aortic aneurysms or dissections as aortic root enlargement from cystic medial changes occur commonly in these patients.

Physical Examination

- There is a systolic murmur from birth (occurs later in life in acquired AS),

- Unlike acquired AS, the contour of the carotid pulse is not a good predictor of severity in congenital AS because it is so variable.

- Because the valve is not calcified early on in the case of a fused valve, a click is present unlike acquired AS.

- Patients often have an S4.

Imaging Studies

- 2 D ECHO plays an important role in the diagnosis of bicuspid AS.

- Short axis is useful, doming of valve can be seen on the parasternal long axis.

- Important to diagnose because of risk of endocarditis and calcification with progressive valvular stenosis.

- Only 25% of patients with congenital AS have AI compared with 75% of cases with acquired AS.

- In 75% of those with acquired AS, there is associated mitral valve disease. This association is rare in congenital AS.

- Congenital AS may occur with one or three cusps, but two cusps is the most common.

- Echocardiographic features that are associated with a poor prognosis in asymptomatic patients and progression to a symptomatic state include moderate to severe calcification and a peak aortic velocity > 4.0 M/s. [6]

<youtube v=8B5BWhPgbjk/>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 1

<googlevideo>3292040052828332033&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 2

<googlevideo>-391308719590697542&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 3

<googlevideo>2514293818722256502&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 4

<googlevideo>3670690104304937807&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 5

<googlevideo>2955895618088483909&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 6

<googlevideo>895529287972799768&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Bicuspid Aortic Valve by Transesophageal Echo 7

<googlevideo>-1456550005760918044&hl=en</googlevideo>

Aortic Subvalvular Stenosis

Epidemiology and Demographics

Aortic subvalvular stenosis is the second most common level of congenital obtruction of LV outflow, located just beneath the aortic valve and occurs in 8-30% of all forms of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. IHSS is not present at birth and is not considered a congenital lesion.

The lesion is caused by accumulation of fibrous elastic tissue which most often

Anatomy

There are several varieties of Congenital Aortic Subvalvular Stenosis (or subaortic stenosis):

- Membranous

- A fixed localized membrane .5 to 2 cm below the level of the aortic valve and attached to the septum and the base of the anterior mitral leaflet.

- Fibromuscular, tunnel

- More commonly there is a fibromuscular membrane or tunnel with a significant muscular component which can sometimes be hard to distinguish from IHSS. This is a more severe form and is often associated with a small aortic root.

- Associated aortic insufficiency (AI) is often present due to the high speed jet of blood through the aortic cusps resulting in fibrosis and retraction.

- Congenital anomalies of the mitral valve (attachment to ventricular septum of accesory

chordae from anterior mitral leaflet, redundant AV valve tissue can also cause subaortic obstruction.

- Aneurysm of the membranous ventricular septum

Clinical Features

- Similar to that of valvular AS. Differentiation difficult.

- AI more common in this form (50 to 75% of patients).

- Symptoms begin in infancy or early adulthood.

Aortic Supravalvular Stenosis

Most uncommon cause of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction accounting for 8% of congenital LVOT obstruction.

Anatomy

- Obstruction occurs just above the coronary ostium at the level of the sinotubular junction:

- Hourglass type (the most common)

- Hypoplastic type: uniform narrowing of the ascending aorta.

- Associated lesion is peripheral pulmonary arterial stenosis

- Because of high perfusion pressure of the coronary arteries there is premature CAD.

- Coronary arteries may be obstructed by an adjacent stenotic ring.

Clinical Features

- 1/3rd of cases are transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait.

- 50% have a characteristically greater pulse and systolic blood pressure in the right carotid and brachial arteries than in the left.

- The systolic murmur is maximal below the right clavicle and radiates primarily to the right carotid artery.

- No ejection click, no diastolic murmur.

Subaortic Membrane

- Sub Aortic Membrane 1

<googlevideo>-3205002409975813384&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Sub Aortic Membrane 2

<googlevideo>-7362420301573743800&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Sub Aortic Membrane 3

<googlevideo>-224747777784565772&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Sub Aortic Membrane 4

<googlevideo>-3036066620374246618&hl=en</googlevideo>

- Sub Aortic membrane 5

<googlevideo>-4319660165214545760&hl=en</googlevideo>

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

Aortic stenosis may be medically treated to control symptoms. Extreme care should be taken to avoid excess vasodilation in the patient with critical aortic stenosis which could precipitate a downward spiral of low forward output, impaired subendocardial perfusion, ischemia and further reductions in forward output.

Mechanical and Device Based Therapy

Aortic stenosis requires aortic valve replacement if medical management does not successfully control symptoms. According to a prospective, single-center, nonrandomized study of 25 patients, percutaneous implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis in high risk patients with aortic stenosis results in marked hemodynamic and clinical improvement when successfully completed.[7]

- Bileaflet Mechanical Aortic Valve

<googlevideo>4541951625687665949&hl=en</googlevideo>

Aortic valvuloplasty

Patient selection and treatment choices

- Surgical Aortic valve replacement is the treatment of choice for aortic stenosis but many patients are not good candidates due to advanced age and multiple co-morbidities

- Percutaneous aortic valve replacement is in its infancy and thus aortic valvuloplasty can offer palliation of symptoms and potentially prolong survival for these high risk patients in class III-IV heart failure

- It can be performed emergently in patients with end-stage heart failure due to aortic stenosis: patients in cardiogenic shock, as a bridge to aortic valve replacement, patients with critical aortic stenosis needing emergent non-cardiac surgery, poor surgical candidates and nonagenerians, patients with congenital or rheumatic aortic stenosis

- Results usually last 6 months up to 2 years (with repeat procedures possible if aortic regurgitation is not severe)

- Valvuloplasty tends to alleviate heart failure symptoms and improve hemodynamics but rarely does it alleviate angina

Technique

The retrograde technique is the most commonly used technique.

- 8 French femoral sheath can usually accommodate a 20 mm balloon and minimizes vascular complications

- Alternatively two 6 Fr sheath from bilateral femoral approach and two smaller balloons can be used

- The letter may be necessary in female elderly patients with concomitant peripheral vascular disease

- 0.035” straight wire is commonly used to cross the valve and advance via pig-tail or Amplatz catheter; Right heart catheterization is done and transaortic gradient is typically measured pre-procedure

- The 0.035” wire is then exchanged for a stiffer 0.038”Amplatz exchange length wire with the tip shaped into a pig-tail shape so as not to injure the LV

- The 20-23 mmX 6 cm balloon is advance over the wire and positioned to straddle the aortic valve

- The balloon is manually inflated with a 60 cc syringe containing diluted contrast (slowly)

- Meticulous control of balloon position must be maintained at all times by backward traction on the balloon to prevent jumping forward and injuring/perforating the LV apex

Complications

- Vascular complications are most common thus suture (Perclose) or Angioseal closure after the procedure in this tenuous patient population is preferable

- It follows that attention to meticulous access technique is mandatory

- Antegrade approach ie venous access with transseptal approach can be done in select patients, however, hemodynamic effects of mitral valve incompetence as a stiff wire is placed across the mitral valve are often poorly tolerated; mitral valve injury has been reported in this approach

Outcomes

- 30% reduction in gradient is expected as the immediate result Patient survival after repeat BAV is higher than that of untreated patients.

Pathological Findings

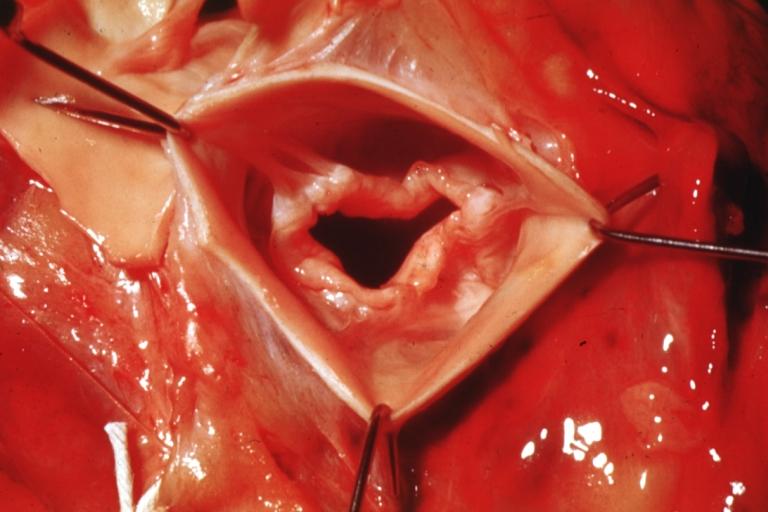

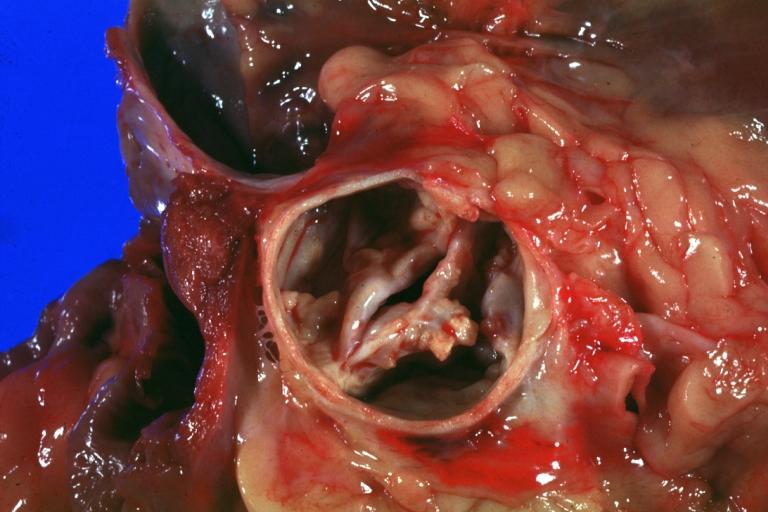

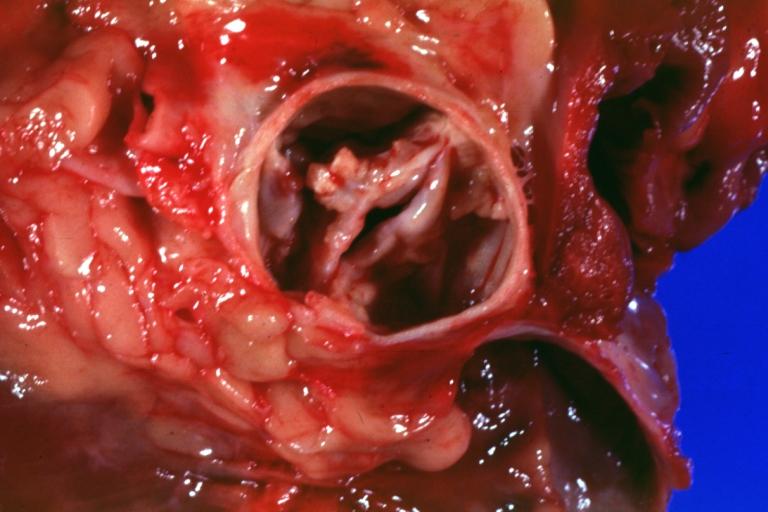

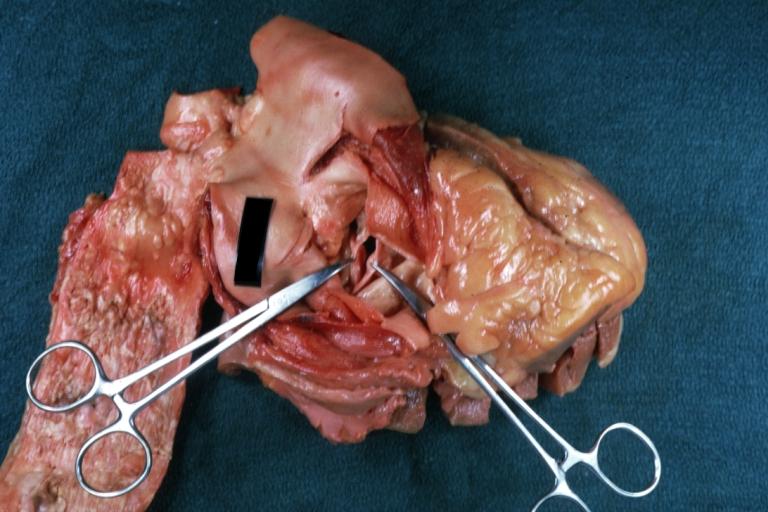

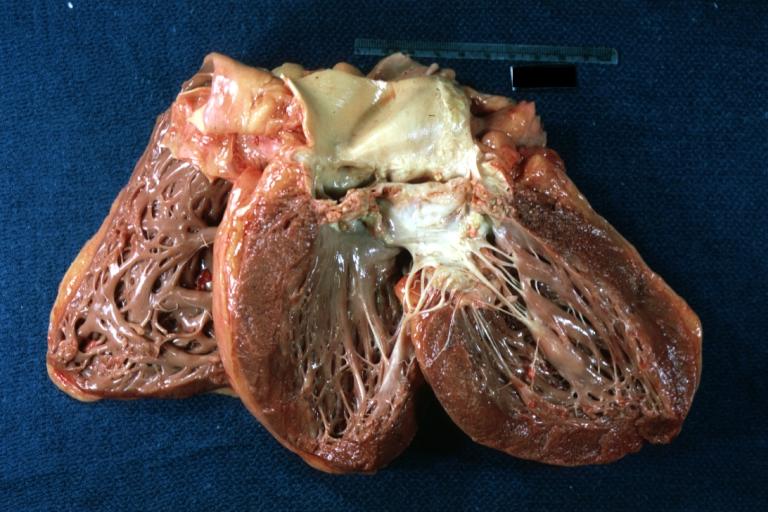

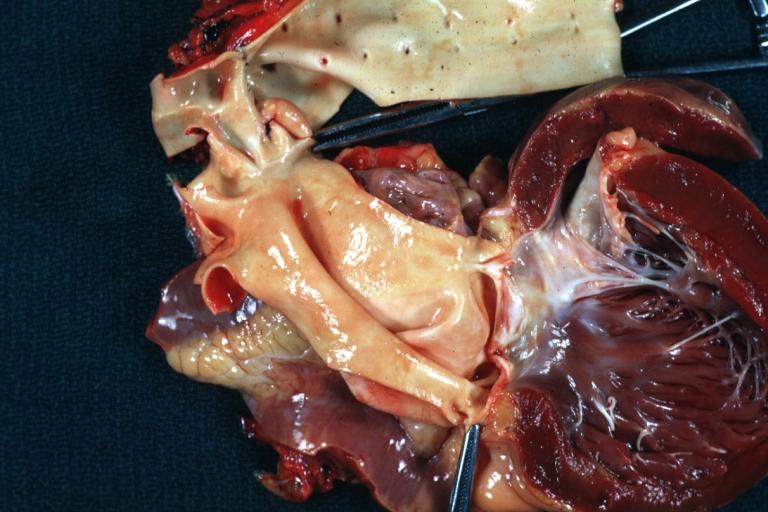

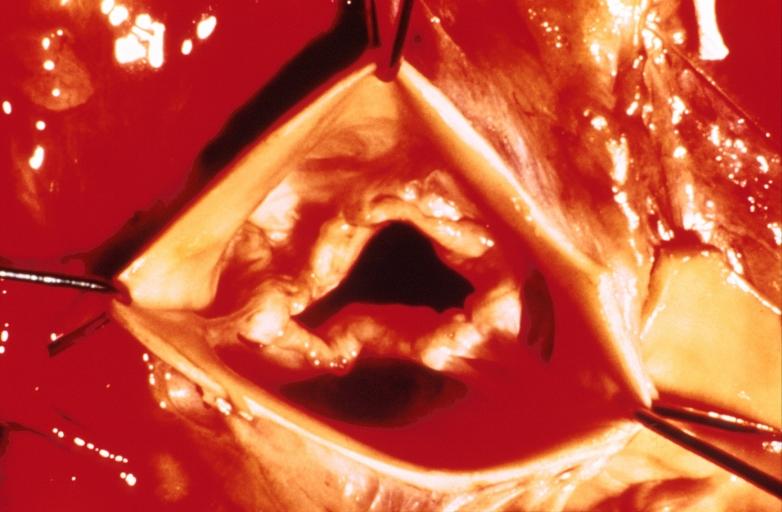

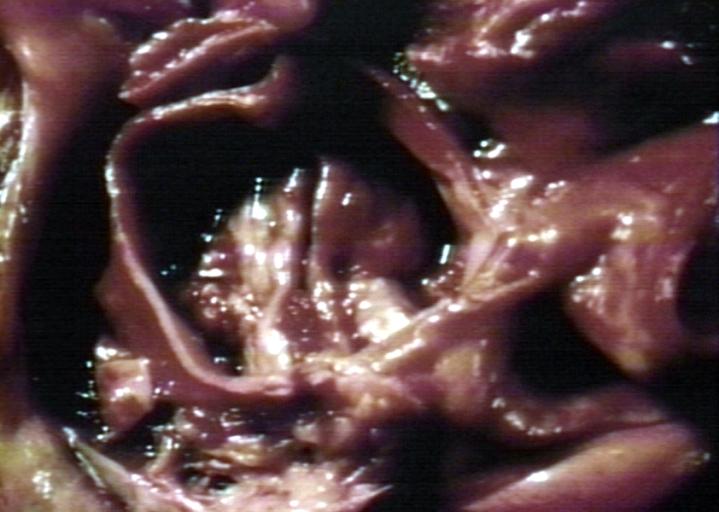

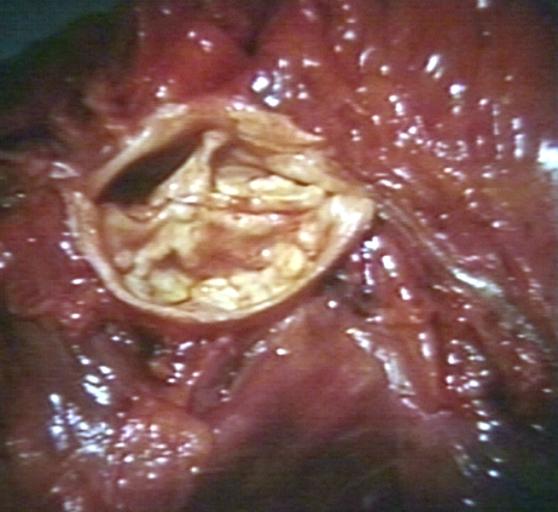

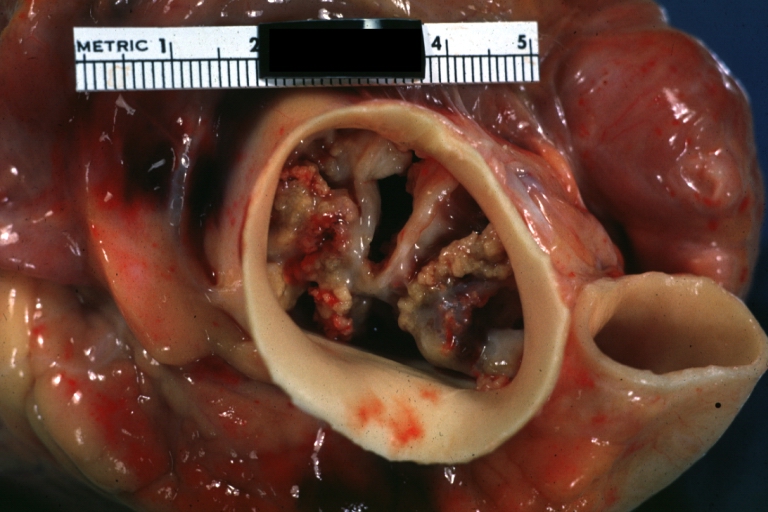

Images shown below are courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission. © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology

-

Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid valve: Gross; excellent image of bicuspid and calcific valve showing a false raphe.

-

Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid valve: Gross; good example of bicuspid valve

-

Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid valve: Gross; image of bicuspid aortic valve, an excellent example

-

Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid valve: Gross; close-up image of bicuspid aortic valve.

-

Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid valve: Gross; close-up image of bicuspid aortic valve.

-

Bicuspid aortic valve

-

Gross natural color opened first portion aortic arch with bicuspid aortic valve shows stenosis and aortic root is dilated

-

Aortic Stenosis Bicuspid: Gross; natural color opened left ventricular outflow tract with calcific masses on valve as well as anterior leaflet mitral valve probably did not cause significant stenosis

-

Bicuspid Aortic Valve with Repaired Aorta Coarctation: Gross natural color opened left ventricular outflow tract with uncomplicated bicuspid aortic valve repaired coarctation barely visible ruptured postoperative young female with ovaries Turner mosaic not ruled out

-

Bicuspid Aortic Stenosis: Gross; fixed tissue

-

Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid: Gross; fixed tissue view of stenotic valve through ventricular outlet track

-

Aortic Stenosis Bicuspid: Gross; fixed tissue. Bicuspid valve and false raphe classical

-

Congenital aortic stenosis: Gangrene toe In Infant: Gross, natural color, 1 month old child with congenital aortic stenosis

-

Unicuspid aortic stenosis

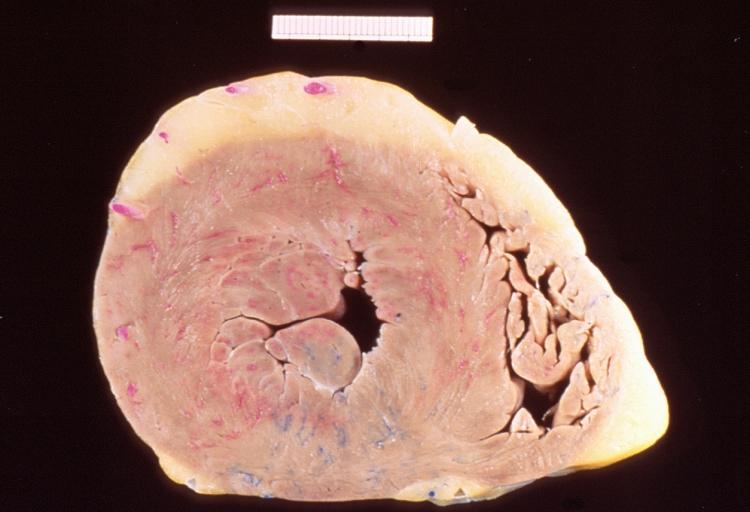

An Autopsy Report

A 68-year-old man initially sought medical advice five years prior to his death. His symptoms at that time were exercise intolerance and occasional peripheral edema. He gave a history of a "heart murmur" that was diagnosed 25 years ago during an employment physical. No follow up care had been given for this murmur.

The patient's terminal admission was for signs of severe heart failure--the patient had marked peripheral edema and shortness of breath and chest x-ray revealed significant cardiac enlargement and pulmonary edema with bilateral pleural effusions. He sustained a cardiac arrest shortly after admission and could not be resuscitated.

Autopsy Findings

Autopsy disclosed a markedly enlarged heart weighing 650 grams and having dilated chambers. The aortic valve was calcified and showed evidence of stenosis and insufficiency. The coronary arteries were narrowed 60 to 70% by atherosclerosis. No acute coronary occlusions were found and there was no evidence of myocardial infarction.

-

This is a gross photograph of a cross section of a normal human heart taken at autopsy (right) and the heart from this case, which demonstrates concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall. Note the marked thickening of the left ventricular wall. There is also moderate thickening of the right ventricular wall.

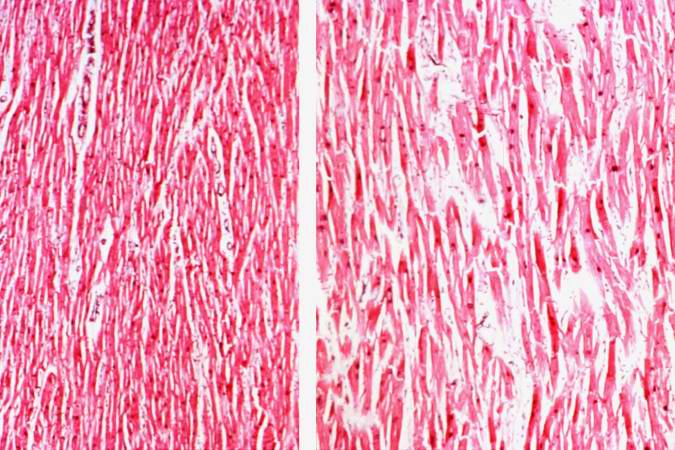

-

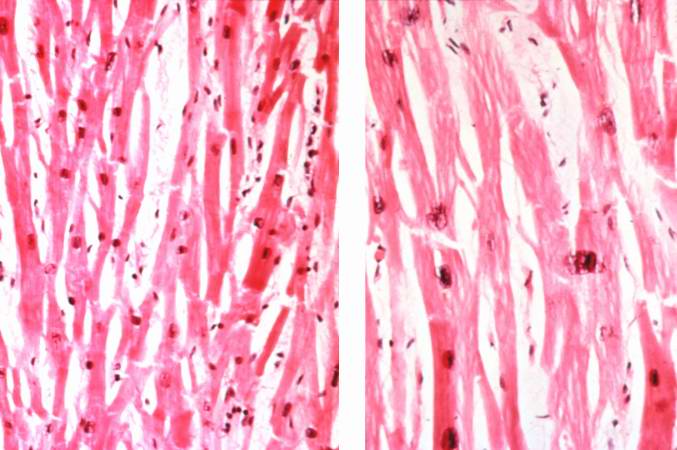

This low-power photomicrograph shows normal myocardium (left) compared to hypertrophied myocardium (right).

-

Normal myocardium (left) is compared here to hypertrophied myocardium (right). The muscle fibers are thicker and the nuclei are larger and darker in the hypertrophied myocardium.The clear spaces between the muscle fibers are due to processing artifacts and are not present during life.

-

Normal myocardium (left) is compared to hypertrophied myocardium (right). This high power view demonstrates the large dark nuclei (arrow) found in hypertrophied cardiac muscle cells. Polyploidy is a common feature in cardiac hypertrophy. Also note the increased size (thickness) of the individual cardiac muscle cell on the right compared to normal cardiac myocytes (left).

Comorbidities

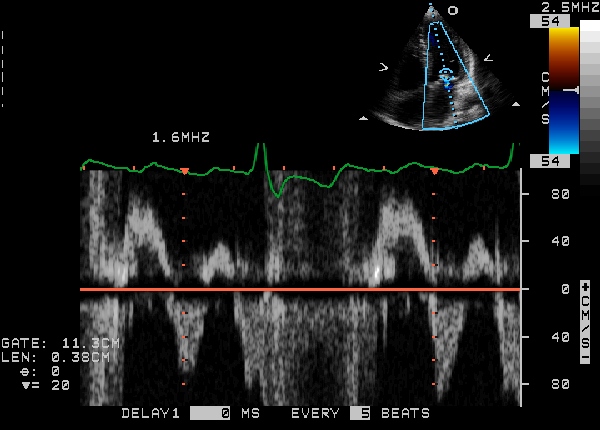

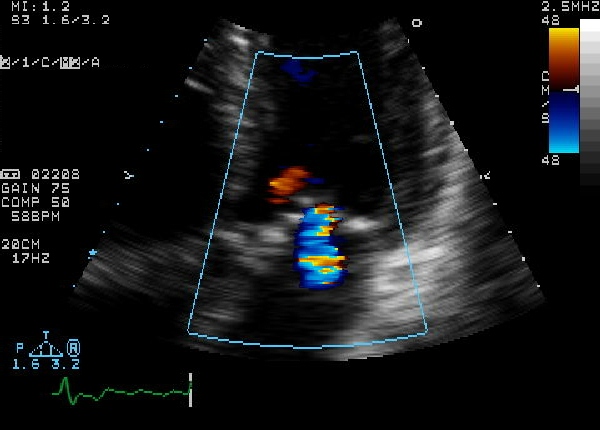

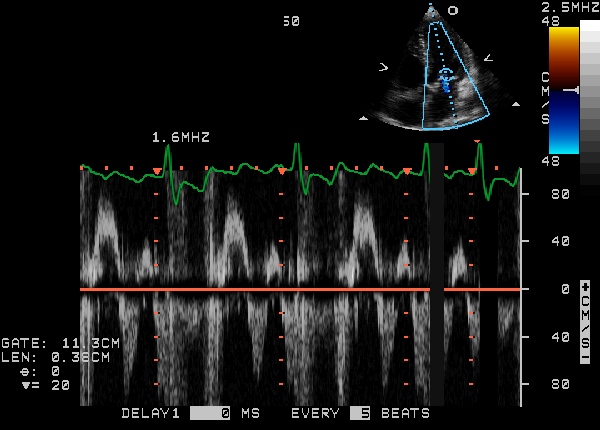

-

Diastolic mitral regurgitation due to severe aortic stenosis

-

Diastolic mitral regurgitation due to severe aortic stenosis

-

Diastolic mitral regurgitation due to severe aortic stenosis

- <googlevideo>424719160215823743&hl=en</googlevideo>

- <googlevideo>-1316686479831791521&hl=en</googlevideo>

References

- ↑ Moura LM, Ramos SF, Zamorano JL; et al. (2007). "Rosuvastatin affecting aortic valve endothelium to slow the progression of aortic stenosis". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (5): 554–61. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.072. PMID 17276178.

- ↑ Lilly LS (editor) (2003). Pathophysiology of Heart Disease (3rd ed. ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-4027-4.

- ↑ http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/277/7/564

- ↑ Etchells E, Bell C, Robb K (1997). "Does this patient have an abnormal systolic murmur?". JAMA. 277 (7): 564–71. PMID 9032164.

- ↑ http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4436

- ↑ Cohn LH, Edmunds LH Jr. Cardiac Surgery in the Adult. McGraw-Hill, 2003.

- ↑ Grube E, Laborde JC, Gerckens U; et al. (2006). "Percutaneous implantation of the CoreValve self-expanding valve prosthesis in high-risk patients with aortic valve disease: the Siegburg first-in-man study". Circulation. 114 (15): 1616–24. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.639450. PMID 17015786.

External links

- Aortic stenosis information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- Mitral Valve Repair at The Mount Sinai Hospital

See also

Additional Reading

- Moss and Adams' Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents Hugh D. Allen, Arthur J. Moss, David J. Driscoll, Forrest H. Adams, Timothy F. Feltes, Robert E. Shaddy, 2007 ISBN 0781786843

- Hurst's the Heart, Fuster V, 12th ed. 2008, ISBN 978-0-07-149928-6

- Willerson JT, Cardiovascular Medicine, 3rd ed., 2007, ISBN 978-1-84628-188-4

de:Aortenstenose (angeboren) no:Aortastenose nn:Aortastenose sv:Aortastenos