Anaplasmosis

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Faizan Sheraz, M.D. [2] Rina Ghorpade, M.B.B.S[3]

- For anaplasmosis in dogs, see Ehrlichiosis (canine). For anaplasmosis in humans, see Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis.

Overview

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis(HGA) is a disease caused by an intraneutrophilic rickettsial parasite of ruminants, Anaplasma phagocytophilum previously known by other names, Ehrlichia'' equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophilum. It is an emerging cause of tick-borne illness in the USA and Europe. The organism infects granulocytes and is transmitted by a number of hematophagous species of ticks most commonly by black-legged deer tick Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. HGA is considered as a zoonotic disease. The disease has a variable presentation in humans, but also often present as a subclinical illness with mild symptoms of fever, myalgia, and malaise. These common symptoms make it difficult to definitively diagnose HGA. Although it present as a mild illness sometimes it leads to hospitalization in 36%, the ICU admission in 7%, and death in 0.6% of cases. This disease can be cured with antimicrobial agent doxycycline, however, minority of patients can have debilitating illness despite antibiotic therapy.

Historical Perspective

HGA was previously known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE). The first human cases were found in Minnesota and Wisconsin in 1993. It was renamed as Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis in 2003. In 1994,the association between Anaplasma phagocytophilum and the development of human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) was identified.There have been several outbreaks of Anaplasmosis , in maine especially in 2008–2017.

Classification

There is no established system for the classification of Anaplasmosis.

Classification based on vectors

The most commonly Anaplasma phagocytophilum is transmitted by two ticks namely, Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. The following table demonstrates the main differentiating points of these two ticks.

| General information | Ixodes scapularis | Ixodes pacificus |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Northeast and the midwestern USA | West coast of the USA |

| Other names | Eastern black-legged tick/deer tick | Western black-legged tick/deer tick |

| Diseases transmitted |

|

|

| Preferred hosts | White-tailed black-tailed deer and large/medium-sized mammals | Columbian black-tailed deer and large/medium-sized mammals |

Pathophysiology

Anaplasmosis(HGA) is transmitted by Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Brief description of the pathophysiological aspects of the disease is provided in the following sections.[1].

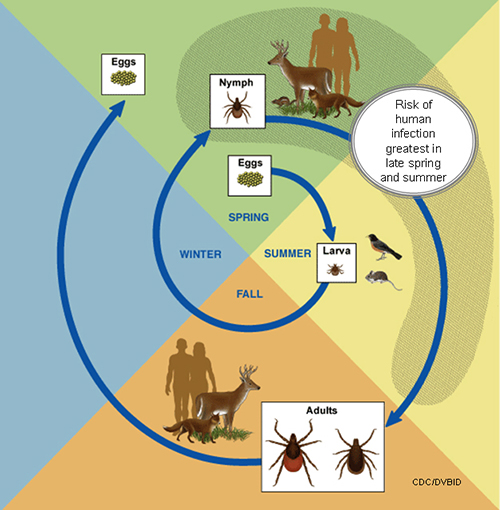

Lifecycle

The life cycle of Ixodes scapularis

An adult female lay eggs in clutches of approximately 1500-3000 eggs in spring, from eggs six-legged larvae emerge. Larvae usually feed on rodent/bird blood and get infected by rickettsial parasites usually in summer. Larvae transformed into an eight-legged structure called nymph, nymphs lie dormant in fall/winter, nymphs start feeding on deer, humans, and dogs in the next spring. Nymphs then molt into adults which also has eight legs, and adults find the third host, these adults mate on or off a host, and once engorged and met, female adult tick thousands of eggs in the clutch before dying.

Pathogenesis

Anaplasma phagocytophilum enters the bloodstream after tick bite through the dermis, and bacteremia develops 4-7 days after tick-bite. It is an obligate intracellular gram-negative organism. After gaining entry into the bloodstream the bacteria infects granulocytes, mainly, neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes. This period of bacteremia is characterized by fever, which can last up to 7 days, and the degree of bacteremia depends on the immune status of the host.

Mechanism of survival inside neutrophils

Anaplasma phagocytophilum has the ability to grow inside the neutrophils because it affects the phagosome-lysosome fusion. Additionally, this bacteria inhibit the respiratory burst of the neutrophils and therefore, preventing the release of reactive oxygen radicals from neutrophils.

Studies have proven that Anaplasma phagocytophilum delays the apoptosis of neutrophils.[2]

Transmission

Vector

Anaplasma phagocytophilum the one causing Anaplasmosis is transmitted by I. scapularis, which also transmits other diseases likeLyme disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesiosis caused by Babesia microti. The coinfection is also common.I. pacificus the western black-legged tick, is the primary vector of HGA in the western United States, and Ixodes ricinus is the presumed vector in Europe.

Reservior

The principle animal reservoirs of HGA are white-tailed deer and white-footed mice.

Other modes of transmission

Even though tick bite is a common mode of transmission of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, it can also occasionally be transmitted by blood transfusion and maternal-fetal transmission.[3][4][3]

Causes

Anaplasmosis is caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

Clinical Features

This infection causes symptoms of fever, headache, and myalgia, nausea/vomiting in the majority of patients, and a macular, maculopapular or petechial skin rash in less than 10% of patients. Neurological symptoms such as neck stiffness and confusion are less common.

Differentiating HGA from other tick-borne diseases

| Disease | Organism | Vector | Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Infection | ||||

| Borreliosis (Lyme Disease) [5] | Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex and B. mayonii | I. scapularis, I. pacificus, I. ricinus, and I. persulcatus | Erythema migrans, flu-like illness(fatigue, fever), Lyme arthritis, neuroborreliosis, and carditis. | |

| Relapsing Fever [6] | Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF): | Borrelia duttoni, Borrelia hermsii, and Borrelia parkerii | Ornithodoros species | Consistently documented high fevers, flu-like illness, headaches, muscular soreness or joint pain, altered mental status, painful urination, rash, and rigors. |

| Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) : | Borrelia recurrentis | Pediculus humanus | ||

| Typhus (Rickettsia) | ||||

| Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor andersoni | Fever, altered mental status, myalgia, rash, and headaches. | |

| Helvetica Spotted Fever [7] | Rickettsia helvetica | Ixodes ricinus | Rash: spotted, red dots. Respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough), muscle pain, and headaches. | |

| Ehrlichiosis (Anaplasmosis) [8] | Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii | Amblyomma americanum, Ixodes scapularis | Fever, headache, chills, malaise, muscle pain, nausea, confusion, conjunctivitis, or rash (60% in children and 30% in adults). | |

| Tularemia [9] | Francisella tularensis | Dermacentor andersoni, Dermacentor variabilis | Ulceroglandular, glandular, oculoglandular, oroglandular, pneumonic, typhoidal. | |

| Viral Infection | ||||

| Tick-borne meningoencephalitis [10] | TBEV virus | Ixodes scapularis, I. ricinus, I. persulcatus | Early Phase: Non-specific symptoms including fever, malaise, anorexia, muscle pains, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. Second Phase: Meningitis symptoms, headache, stiff neck, encephalitis, drowsiness, sensory disturbances, and potential paralysis. | |

| Colorado Tick Fever [11] | CTF virus | Dermacentor andersoni | Common symptoms include fever, chills, headache, body aches, and lethargy. Other symptoms associated with the disease include sore throat, abdominal pain, vomiting, and a skin rash. A biphasic fever is a hallmark of Colorado Tick Fever and presents in nearly 50% of infected patients. | |

| Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever | CCHF virus | Hyalomma marginatum, Rhipicephalus bursa | Initially infected patients will likely feel a few of the following symptoms: headache, high fever, back and joint pain, stomach pain, vomiting, flushed face, red throat petechiae of the palate, and potentially changes in mood as well as sensory perception. | |

| Protozoan Infection | ||||

| Babesiosis [12] | Babesia microti, Babesia divergens, Babesia equi | Ixodes scapularis, I. pacificus | Non-specific flu-like symptoms. | |

Epidemiology and Demographics

- In the USA the annual incidence is 6.3 million per year and it is rising. However the case fatality rate has remained low, at less than 1%.

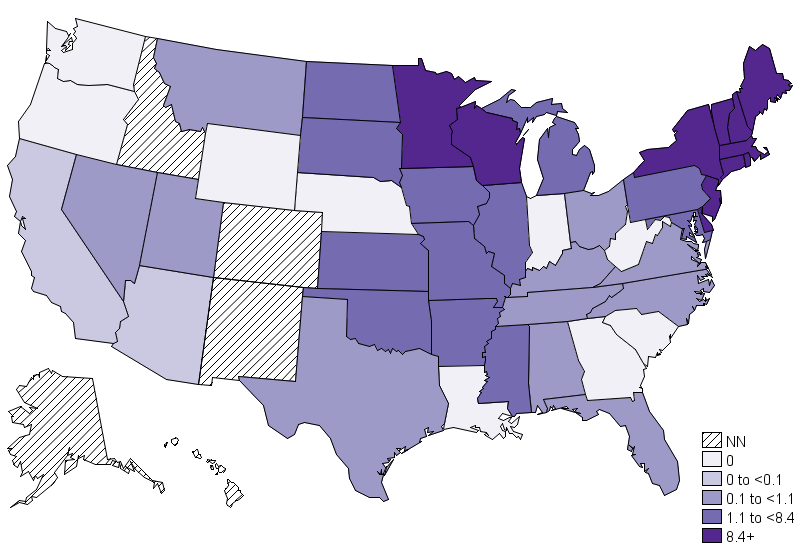

- The endemic area of HGA is the upper midwestern and the northeastern United States, eight states (Vermont, Maine, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, and New York) have the highest annual incidence of HGA according to the Center for Disease control(CDC). This geographic area coincides with the distribution of black-legged deer tick Ixodes scapularis. There is a seasonal variation of the reported incidence, with the highest rate in summer months, most commonly June and July. Patients of all age groups may develop HGA, however, it commonly affects the individuals over age 40.The incidence of HGA in more in males as compared to females.There is no racial predilection for HGA[13]

Risk factors

Immunocompromised patients (HIV positives, cancer patients on chemotherapy, patients with transplanted organs) are at risk of severe disease with high mortality.

Screnning

There are no methods available to screen HGA.

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

The average incubation period of HGA is 5.5 days after a tick bite.[14] HGA mainly presents as an acute illness, but in some cases, the presentation is asymptomatic and self-limited. The most common clinical features are fever, myalgia, headache, and maculopapular rash.

Complications

If left untreated HGA can lead to seizures, coma, respiratory, and renal failure. It can also cause congestive heart failure, myocarditis, and pericardial effusion. Many fatal opportunistic infections, including herpes simplex esophagitis, invasive aspergillosis, and candidiasis can occur.[15]

Prognosis

Patients who receive treatment with doxycycline or rifampicin usually have the resolution of symptoms within 48 hours, those who do not receive the adequate treatment can have bacteremia for up to 30 days, and have prolonged symptoms. However, all patients recover within 60 days regardless of antibiotic treatment[16]. Prognosis is generally excellent, and mortality rate is approximately 1%.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Study of Choice

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of HGA is usually presumptive, and it is considered when a patient from an endemic area presents with an acute febrile illness, a history of tick bite characteristic laboratory findings.

History and Symptoms

Anaplasmosis can be asymptomatic, however if present the common symptoms may include:[15]

- Fever

- Headache

- Rash can be macular, maculopapular rash or petechial

- Myalgia

- Arthralgia

- Neck stiffness

- Confusion

- Nausea

- Vomiting

Physical Examination

Physical examination may be remarkable for rash in a minority of patients, children can present with lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory Findings

Anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, raised plasma levels of aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, and alkaline phosphatase [17]

Electrocardiogram

There are no ECG findings associated with Anaplasmosis.

X-ray

There are no X-ray findings associated with Anaplasmosis.

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

There are no echocardiography/ultrasoundfindings associated with Anaplasmosis.

CT scan

There are no CT scan findings associated with Anaplasmosis.

MRI

There are no MRI findings associated with Anaplasmosis.

Other Imaging Findings

There are no other imaging findings associated with Anaplasmosis.

Other Diagnostic Studies

The other diagnostic studies include serological tests like Indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test to confirm the diagnosis of HGA. A four-fold rise in Anti-IgG antibodies against Anaplasma phagocytophilum is considered indicative of current or past infection. This test has a sensitivity of 95% to detect the current infection. ELISA is also used to diagnose HGA, but is not as sensitive asIndirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) to detect the current infection. Blood culture has no role in the diagnosis of HGA.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

Treatment is indicated in all symptomatic patients. [18]

Preferred regimen: Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid (or IV for those patients unable to take oral medication) for 10 days Alternative regimen: Rifampin 300 mg PO bid for 7–10 days for patients with mild illness due to HGA who are not optimally suited for doxycycline treatment because of a history of drug allergy, pregnancy, or age <8 years) Pediatric regimen: Children ≥ 8 years of age Preferred regimen: Doxycycline 4 mg/kg/day PO bid (Maximum, 100 mg/dose) (or IV for children unable to take an oral medication) for 10 days Children < 8 years of age

In pregnant women Rifampin 10 mg/kg bid (Maximum, 300 mg/dose) for 4-5 days Note (1): If the patient has concomitant Lyme disease, then Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses (maximum of 500 mg per dose) OR Cefuroxime axetil 30 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses (maximum of 500 mg per dose) should be initiated at the conclusion of the course of Doxycycline to complete a 14-day total course of antibiotic therapy Note (2): Rifampin is not effective therapy for Lyme disease, patients coinfected with B. burgdorferi should also be treated with Amoxicillin OR Cefuroxime axetil Treatment of pregnant patients Generally tetracyclins are considered as a contraindication during pregnancy due to hepatotoxicity to the mother, and adverse effect on fetal bones on teeth formation, however, doxycycline rarely causes these side effects. [19]

Alternatively, Rifampin can be used in pregnant patients.[20]

Surgery

Surgical intervention is not recommended for the management of Anaplasmosis.

Primary Prevention

- The best way to prevent infection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum is the use of insect repellents such as DEET (N, N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamid) or permethrin.

- Thorough bathing after outdoor activities, the prompt examination of the skin, and removal of the tick.

- Wearing protective clothing for outdoor activities or avoiding outdoor activities in endemic areas and putting all the clothes in dryer for short time

- Use of prophylaxis antibiotics such as doxycycline is not recommended, and there is no vaccine available for the prevention of HGA.

Secondary Prevention

References

- ↑ Dumler JS (2012). "The biological basis of severe outcomes in Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection". FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 64 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00909.x. PMC 3256277. PMID 22098465.

- ↑ Woldehiwet Z (2008). "Immune evasion and immunosuppression by Anaplasma phagocytophilum, the causative agent of tick-borne fever of ruminants and human granulocytic anaplasmosis". Vet J. 175 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.11.019. PMID 17275372.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fine, Antonella B.; Sweeney, Joseph D.; Nixon, Christian P.; Knoll, Bettina M. (2016). "Transfusion-transmitted anaplasmosis from a leukoreduced platelet pool". Transfusion. 56 (3): 699–704. doi:10.1111/trf.13392. ISSN 0041-1132.

- ↑ "Anaplasma phagocytophilum Transmitted Through Blood Transfusion—Minnesota 2007". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 53 (5): 643–645. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.010. ISSN 0196-0644.

- ↑ Lyme Disease Information for HealthCare Professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Relapsing Fever Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/ Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/ Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Disease index General Information (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/babesiosis/health_professionals/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). \http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ General Disease Information (TBE). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/tbe/ Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ General Tick Deisease Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/coloradotickfever/index.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Babesiosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/babesiosis/disease.htmlAccessed December 8, 2015.

- ↑ F. Scott Dahlgren, Kristen Nichols Heitman, Naomi A. Drexler, Robert F. Massung & Casey Barton Behravesh (2015). "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis in the United States from 2008 to 2012: a summary of national surveillance data". The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 93 (1): 66–72. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0122. PMID 25870428. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ ME Aguero-Rosenfeld, HW Horowitz, GP Wormser, DF McKenna, J. Nowakowski, J. Munoz & JS Dumler (1996). "Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: a case series from a medical center in New York State". Annals of internal medicine. 125 (11): 904–908. doi:10.7326 / 0003-4819-125-11-199612010-00006 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 8967671. Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 Zhang L, Liu Y, Ni D, Li Q, Yu Y, Yu XJ, Wan K, Li D, Liang G, Jiang X, Jing H, Run J, Luan M, Fu X, Zhang J, Yang W, Wang Y, Dumler JS, Feng Z, Ren J, Xu J (November 2008). "Nosocomial transmission of human granulocytic anaplasmosis in China". JAMA. 300 (19): 2263–70. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.626. PMID 19017912.

- ↑ Bakken JS, Dumler JS (2015). "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis". Infect Dis Clin North Am. 29 (2): 341–55. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.007. PMC 4441757. PMID 25999228.

- ↑ Bakken JS, Krueth J, Wilson-Nordskog C, Tilden RL, Asanovich K, Dumler JS (1996). "Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis". JAMA. 275 (3): 199–205. PMID 8604172.

- ↑ Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS; et al. (2006). "The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin Infect Dis. 43 (9): 1089–134. doi:10.1086/508667. PMID 17029130.

- ↑ Cross R, Ling C, Day NP, McGready R, Paris DH (2016). "Revisiting doxycycline in pregnancy and early childhood--time to rebuild its reputation?". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 15 (3): 367–82. doi:10.1517/14740338.2016.1133584. PMC 4898140. PMID 26680308.

- ↑ Dhand A, Nadelman RB, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Haddad FA, Stokes DP, Horowitz HW (2007). "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis during pregnancy: case series and literature review". Clin Infect Dis. 45 (5): 589–93. doi:10.1086/520659. PMID 17682993.