Malaria causes

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

|

Malaria Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Malaria causes On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Malaria causes |

Overview

Malaria is a vector-borne infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites. It is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, including parts of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Each year, it causes disease in approximately 650 million people and kills between one and three million, most of them young children in Sub-Saharan Africa. Malaria is commonly associated with poverty, but is also a cause of poverty and a major hindrance to economic development.

Causes

Malaria parasites

Malaria is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium (phylum Apicomplexa). In humans malaria is caused by P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. vivax. P. vivax is the most common cause of infection, responsible for about 80 % of all malaria cases. However, P. falciparum is the most important cause of disease, and responsible for about 15% of infections and 90% of deaths.[1] Parasitic Plasmodium species also infect birds, reptiles, monkeys, chimpanzees and rodents.[2] There have been documented human infections with several simian species of malaria, namely P. knowlesi, P. inui, P. cynomolgi[3], P. simiovale, P. brazilianum, P. schwetzi and P. simium; however these are mostly of limited public health importance. Although avian malaria can kill chickens and turkeys, this disease does not cause serious economic losses to poultry farmers.[4] However, since being accidentally introduced by humans it has decimated the endemic birds of Hawaii, which evolved in its absence and lack any resistance to it.[5]

Mosquito vectors and the Plasmodium life cycle

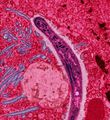

The parasite's primary (definitive) hosts and transmission vectors are female mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus. Young mosquitoes first ingest the malaria parasite by feeding on an infected human carrier and the infected Anopheles mosquitoes carry Plasmodium sporozoites in their salivary glands. A mosquito becomes infected when it takes a blood meal from an infected human. Once ingested, the parasite gametocytes taken up in the blood will further differentiate into male or female gametes and then fuse in the mosquito gut. This produces an ookinete that penetrates the gut lining and produces an oocyst in the gut wall. When the oocyst ruptures, it releases sporozoites that migrate through the mosquito's body to the salivary glands, where they are then ready to infect a new human host. This type of transmission is occasionally referred to as anterior station transfer.[6] The sporozoites are injected into the skin, alongside saliva, when the mosquito takes a subsequent blood meal.

Only female mosquitoes feed on blood, thus males do not transmit the disease. The females of the Anopheles genus of mosquito prefer to feed at night. They usually start searching for a meal at dusk, and will continue throughout the night until taking a meal. Malaria parasites can also be transmitted by blood transfusions, although this is rare.[7]

References

- ↑ Mendis K, Sina B, Marchesini P, Carter R (2001). "The neglected burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria" (PDF). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 64 (1-2 Suppl): 97–106. PMID 11425182.

- ↑ Escalante A, Ayala F (1994). "Phylogeny of the malarial genus Plasmodium, derived from rRNA gene sequences". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91 (24): 11373–7. PMID 7972067.

- ↑ Garnham, PCC (1966). Malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. Blackwell Scientific Publications. Unknown parameter

|Location=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ↑ Investing in Animal Health Research to Alleviate Poverty. International Livestock Research Institute. Permin A. and Madsen M. (2001) Appendix 2: review on disease occurrence and impact (smallholder poultry). Accessed 29 Oct 2006

- ↑ Atkinson CT, Woods KL, Dusek RJ, Sileo LS, Iko WM (1995). "Wildlife disease and conservation in Hawaii: pathogenicity of avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) in experimentally infected iiwi (Vestiaria coccinea)". Parasitology. 111 Suppl: S59–69. PMID 8632925.

- ↑ Talman A, Domarle O, McKenzie F, Ariey F, Robert V. "Gametocytogenesis: the puberty of Plasmodium falciparum". Malar J. 3: 24. PMID 15253774.

- ↑ Marcucci C, Madjdpour C, Spahn D. "Allogeneic blood transfusions: benefit, risks and clinical indications in countries with a low or high human development index". Br Med Bull. 70: 15–28. PMID 15339855.