Toxocara infection

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [1] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Also known as: Toxocariasis, toxocaral larva migrans, visceral larva migrans, ocular larva migrans, and covert toxocariasis.

Overview

Toxocariasis (TOX-o-kah-RYE-uh-sis) is an infection caused by parasitic roundworms found in the intestines of dogs (Toxocara canis) and cats (T. cati)

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/submenus/sub_toxocariasis.htm

Epidemiology and Demographics

Toxocariasis occurs worldwide.

References

http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Toxocariasis.htm

Risk Factors

In most cases, Toxocara infections are not serious, and many people, especially adults infected by a small number of larvae (immature worms), may not notice any symptoms. The most severe cases are rare, but are more likely to occur in young children, who often play in dirt, or eat dirt (pica) contaminated by dog or cat stool.

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/toxocara/factsht_toxocara.htm

Pathophysiology & Etiology

Toxocariasis is a zoonotic (animal to human) infection caused by larvae of Toxocara canis (dog roundworm) and less frequently of T. cati (cat roundworm), two nematode parasites of animals.

Toxocara canis accomplishes its life cycle in dogs, with humans acquiring the infection as accidental hosts. Following ingestion by dogs, the infective eggs hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall and migrate into various tissues, where they encyst if the dog is older than 5 weeks. In younger dogs, the larvae migrate through the lungs, bronchial tree, and esophagus; adult worms develop and oviposit in the small intestine. In the older dogs, the encysted stages are reactivated during pregnancy, and infect by the transplacental and transmammary routes the puppies, in whose small intestine adult worms become established. Thus, infective eggs are excreted both by lactating bitches and puppies. Humans are accidental hosts who become infected by ingesting infective eggs in contaminated soil. After ingestion, the eggs hatch and larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and are carried by the circulation to a wide variety of tissues (liver, heart, lungs, brain, muscle, eyes). While the larvae do not undergo any further development in these sites, they can cause severe local reactions that are the basis of toxocariasis. The two main clinical presentations of toxocariasis are visceral larva migrans (VLM) and ocular larva migrans (OLM).

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/toxocara/factsht_toxocara.htm

http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Toxocariasis.htm

Diagnosis

Antibody Detection

Antibody detection tests are the only means of confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of visceral larva migrans (VLM), ocular larva migrans (OLM), and covert toxocariasis (CT), the most common clinical syndromes associated with Toxocara infections. The currently recommended serologic test for toxocariasis is enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with larval stage antigens extracted from embryonated eggs or released in vitro by cultured infective larvae. The latter, Toxocara excretory-secretory (TES) antigens, are preferable to larval extracts because they are convenient to produce and because an absorption-purification step is not required for obtaining maximum specificity. Evaluation of the true sensitivity and specificity of serologic tests for toxocariasis in human populations is not possible because of the lack of parasitologic methods to detect Toxocara parasites. These inherent problems result in underestimations of sensitivity and specificity. Evaluation of the Toxocara EIA in groups of patients with presumptive diagnoses of VLM or OLM indicated sensitivity of 78% and 73%, respectively, at a titer of >1:32. When the cutoff titer for OLM cases was lowered to 1:8, sensitivity was increased to 90%. Further confirmation of the specificity of the serologic diagnosis of OLM can be obtained by testing aqueous or vitreous humor samples for antibodies. Specificity has been reported to be >90% at a titer of >1:32. When interpreting the serologic findings, clinicians must be aware that a measurable titer does not necessarily indicate current clinical Toxocara canis infection. In most human populations, a small number of those tested have positive EIA titers that apparently reflect the prevalence of asymptomatic toxocariasis. In the United States, 2.8% (cutoff titer 1:32) of nearly 9,000 persons tested showed such positive reactions, but the percentage but varied significantly according to age, race, and socioeconomic status.

References

http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Toxocariasis.htm

History and Symptoms

There are two major forms of toxocariasis:

- Ocular larva migrans (OLM):

Toxocara infections can cause OLM, an eye disease that can cause blindness. OLM occurs when a microscopic worm enters the eye; it may cause inflammation and formation of a scar on the retina. Each year more than 700 people infected with Toxocara experience permanent partial loss of vision.

- Visceral larva migrans (VLM):

Heavier, or repeated Toxocara infections, while rare, can cause VLM, a disease that causes swelling of the body’s organs or central nervous system. Symptoms of VLM, which are caused by the movement of the worms through the body, include fever, coughing, asthma, or pneumonia.

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/toxocara/factsht_toxocara.htm

Laboratory Findings

In this parasitic disease the diagnosis does not rest on identification of the parasite. Since the larvae do not develop into adults in humans, a stool examination would not detect any Toxocara eggs. However, the presence of Ascaris and Trichuris eggs in feces, indicating fecal exposure, increases the probability of Toxocara in the tissues.

For both VLM and OLM, a presumptive diagnosis rests on clinical signs, history of exposure to puppies, laboratory findings (including eosinophilia), and the detection of antibodies to Toxocara.

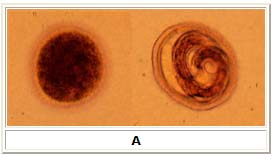

A: Eggs of Toxocara canis. These eggs are passed in dog feces, especially puppies' feces. Human infections with Toxocara do not produce or excrete eggs, and therefore eggs are not a diagnostic finding in human toxocariasis. The egg to the left is fertilized but not yet embryonated, while the egg to the right contains a well developed larva. The latter egg would be infective if ingested by a human (frequently, a child).

References

http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Toxocariasis.htm

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

In most cases, Toxocara infections are not serious, and many people, especially adults infected by a small number of larvae (immature worms), may not notice any symptoms. The most severe cases are rare, but are more likely to occur in young children, who often play in dirt, or eat dirt (pica) contaminated by dog or cat stool.

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/toxocara/factsht_toxocara.htm

Treatment

VLM is treated with antiparasitic drugs, usually in combination with anti-inflammatory medications. Treatment of OLM is more difficult and usually consists of measures to prevent progressive damage to the eye.

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/toxocara/factsht_toxocara.htm

Primary Prevention

- Have your veterinarian treat your dogs and cats, especially young animals, regularly for worms.

- Wash your hands well with soap and water after playing with your pets and after outdoor activities, especially before you eat. Teach children to always wash their hands after playing with dogs and cats and after playing outdoors.

- Do not allow children to play in areas that are soiled with pet or other animal stool.

- Clean your pet’s living area at least once a week. Feces should be either buried or bagged and disposed of in the trash.

- Teach children that it is dangerous to eat dirt or soil.

References

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/toxocara/factsht_toxocara.htm

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D.