Tetralogy of Fallot pathophysiology

|

Tetralogy of fallot Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

|

|

Tetralogy of Fallot pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Tetralogy of Fallot pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Tetralogy of Fallot pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editors-In-Chief: Priyamvada Singh, M.B.B.S. [2], Keri Shafer, M.D. [3]; Omar Toubat; Assistant Editor-In-Chief: Kristin Feeney, B.S. [4]

Overview

Tetralogy of Fallot is a congenital heart lesion characterized by a constellation of four morphologic abnormalities present in the newborn heart. These features include a ventricular septal defect, overriding aorta, pulmonary stenosis, and right ventricular hypertrophy. The obstruction of right ventricular outflow in tetralogy of Fallot causes blood to shunt or flow from the right to left side of heart through the ventricular septal defect. This causes right ventricular hypertrophy and eventual right sided heart failure. There is flow of deoxygenated venous blood from the right side of the heart to the systemic circulation resulting in cyanosis.

Pathophysiology

- Tetralogy of Fallot results in cyanosis, (hypoxia or low oxygenation) of the blood due to mixing of deoxygenated venous blood from the right ventricle with oxygenated blood in the left ventricle through the ventricular septal defect and preferential flow of both oxygenated and deoxygenated blood from the ventricles through the aorta because of obstruction to flow through the pulmonary valve. This is known as a right-to-left shunt. If pulmonary blood flow is dramatically reduced, pulmonary blood flow may depend on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or bronchial collaterals.

- If obstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract is minimal, the intracardiac shunt may be mostly from left to right, and this may result in what is termed a pink tet or pink tetralogy. Although cyanosis is absent on clinical exam, laboratory testing will often show systemic oxygen desaturation.

- Children with tetralogy of Fallot may develop acute severe cyanosis or hypoxic tet spells. The mechanism underlying these episodes is not entirely clear, but may be due to spasm of the infundibular septum and the right ventricular outflow tract. Whatever the mechanism, there is an increase in resistance to blood flow to the lungs with increased preferential flow of desaturated blood to the systemic circulation. The child will often squat during a tet spell to improve venous return to the right side of the heart. Squatting increases the systemic vascular resistance and thereby shunts flow to pulmonary circuit. These spells can be fatal, and can occur in patients who are not cyanotic.

Embryology

Cardiac Septation

Subsequent to the lateral folding and looping events that give rise to the primitive heart tube are a series of complex septation processes that will ultimately complete morphogenesis of the four chambered heart. Thus, the goals of cardiac septation are two-fold:

- To create four distinct cardiac chambers

- To correctly position the great vessels relative to these chambers

Improper execution of these septation events can give rise to many congenital heart defects, such as Tetralogy of Fallot.

Morphologic Basis for Teratology of Fallot

The morphologic basis for Tetralogy of Fallot is the result of improper positioning of the outlet septum.[1] In the normal heart, the outlet septum is an indistinguishable component of the crista supraventricularis that communicates with the septomarginal trabeculae to divide the right and left ventricular cavities.[2] In Tetralogy of Fallot, proper ventricular septation is perturbed by anterocephalad displacement of the outlet septum relative to the septomarginal trabecula.[3] The direct consequence of this malalignment is an overriding aortic orifice and a ventricular septal defect, resulting in an intracardiac right to left shunt of blood. In addition, anterocephalad displacement of the outlet septum indirectly predisposes the pulmonary trunk to stenosis in the setting of septoparietal trabecular hypertrophy. Together, the displacement of the outlet septum coupled with the hypertrophic arrangement of the septoparietal trabeculae account for the three anatomical cardinal defects in Tetralogy of Fallot - aortic dextroposition, interventricular communication (VSD), and pulmonary stenosis. The fourth defect - right ventricular hypertrophy - is a hemodynamic consequence of these three morphologic changes, as the right ventricle physiologically adapts to the increased resistance of a stenotic pulmonary trunk.[1]

Genetics

The cellular processes that underlie cardiogenesis are extensively regulated in the developing heart. Proper cardiac development requires the complex orchestration of cardiac transcription factors and signaling pathways in a spatiotemporal specific manner.

Traditional genetic studies have implicated mutations in numerous genes encoding cardiac transcription factors and cell signaling proteins in the development of Teratology of Fallot. Specifically, heterozygous mutations in NKX2-5, HAND1, TBX5, and GATA4 have been reported in familial forms of disease.[4] [5] [6] Many of these single gene mutations result in haploinsufficiency and suggest a dose dependent relationship between genetic expression and disease.[7] While the mechanistic basis of this relationship is currently poorly understood, it is hypothesized that disruption of the direct protein-protein interactions that allow these transcription factors to work synergistically impedes the activation of downstream targets and signaling pathways central to cardiac morphogenesis.[8] [9] In addition, recent whole-exome sequencing investigations have introduced a novel role for epigenetic dysregulation in the pathogenesis of Teratology of Fallot. [7] [10] Aberrant epigenetic modifications are thought to provide an alternative mechanism to perturb normal spatiotemporal expression of these essential developmental proteins.

Associated Conditions

- Right aortic arch seen in 25% of patients.

- Ostium secondum seen in 15% of patients.

- Coronary artery anomalies mainly LAD from RCA or right sinus valsalve is seen.

- Associated abnormalities include cleft lip, cleft palate, hypospadias, skeletal and craniofacial abnormalities.

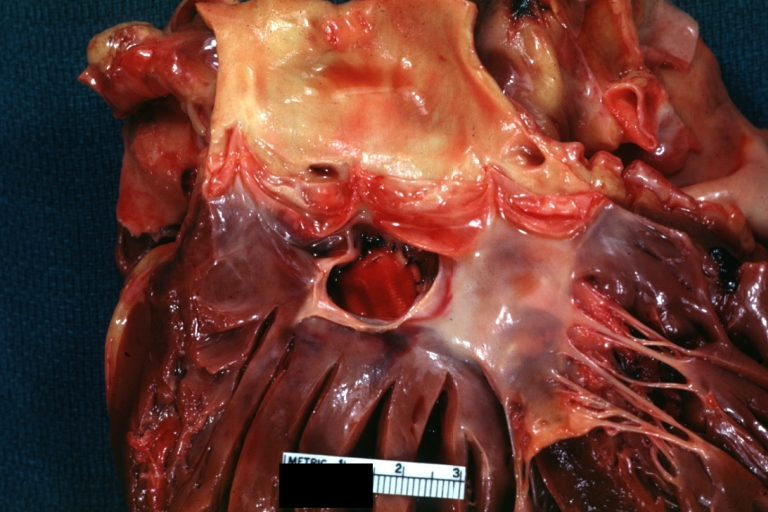

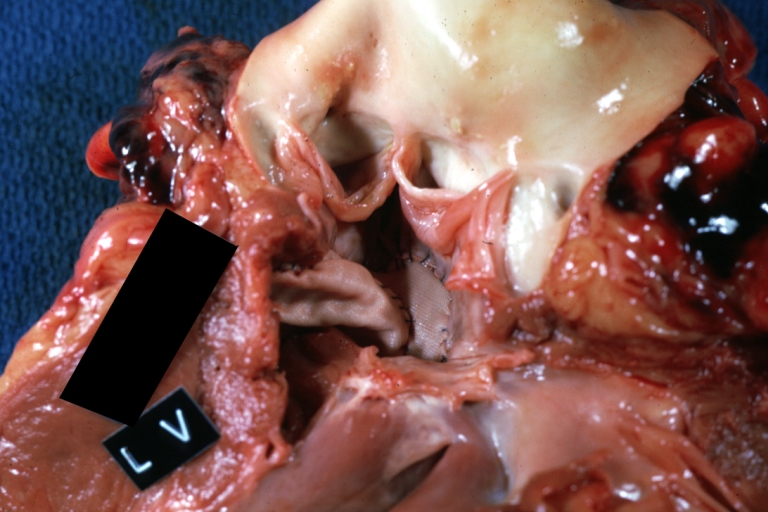

Gross Pathology

-

Tetralogy of Fallot: Gross, a good example of repaired perimembranous septal defect

-

Tetralogy of Fallot: Gross, close-up of aortic valve with subvalvular septal defect with Dacron patch (very good example)

Videos

{{#ev:youtube|b-TkE_wygT4}}

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anderson RH, Jacobs ML (2008). "The anatomy of tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary stenosis". Cardiol Young. 18 Suppl 3: 12–21. doi:10.1017/S1047951108003259. PMID 19094375.

- ↑ Bashore TM (2007). "Adult congenital heart disease: right ventricular outflow tract lesions". Circulation. 115 (14): 1933–47. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592345. PMID 17420363.

- ↑ Bailliard F, Anderson RH (2009). "Tetralogy of Fallot". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 4: 2. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-2. PMC 2651859. PMID 19144126.

- ↑ Olson EN (2006). "Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart". Science. 313 (5795): 1922–7. doi:10.1126/science.1132292. PMID 17008524.

- ↑ Yang YQ, Gharibeh L, Li RG, Xin YF, Wang J, Liu ZM; et al. (2013). "GATA4 loss-of-function mutations underlie familial tetralogy of fallot". Hum Mutat. 34 (12): 1662–71. doi:10.1002/humu.22434. PMID 24000169.

- ↑ Bruneau BG (2008). "The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease". Nature. 451 (7181): 943–8. doi:10.1038/nature06801. PMID 18288184.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bruneau BG, Srivastava D (2014). "Congenital heart disease: entering a new era of human genetics". Circ Res. 114 (4): 598–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.303060. PMID 24526674.

- ↑ Hiroi Y, Kudoh S, Monzen K, Ikeda Y, Yazaki Y, Nagai R; et al. (2001). "Tbx5 associates with Nkx2-5 and synergistically promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation". Nat Genet. 28 (3): 276–80. doi:10.1038/90123. PMID 11431700.

- ↑ Garg V, Kathiriya IS, Barnes R, Schluterman MK, King IN, Butler CA; et al. (2003). "GATA4 mutations cause human congenital heart defects and reveal an interaction with TBX5". Nature. 424 (6947): 443–7. doi:10.1038/nature01827. PMID 12845333.

- ↑ Sheng W, Qian Y, Wang H, Ma X, Zhang P, Diao L; et al. (2013). "DNA methylation status of NKX2-5, GATA4 and HAND1 in patients with tetralogy of fallot". BMC Med Genomics. 6: 46. doi:10.1186/1755-8794-6-46. PMC 3819647. PMID 24182332.