Sturge-Weber syndrome

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Jesus Rosario Hernandez, M.D. [2] Rina Ghorpade, M.B.B.S[3]

Synonyms and keywords: Encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis.

Overview

Sturge-Weber syndrome(SWS), sometimes referred to as encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, is an extremely rare congenital neurological and skin disorder. It is one of the phakomatoses, and is often associated with port-wine stains of the face, which is a capillary malformation, glaucoma, seizures, mental retardation, and ipsilateral leptomeningeal angioma. It is caused by an arteriovenous malformation that occurs in the cerebrum of the brain on the same side as the physical signs described above. Normally, only one side of the head is affected. It is an embryonal developmental anomaly resulting from errors in mesodermal and ectodermal development. Unlike other neurocutaneous disorders (phakomatoses), Sturge-Weber does not have a hereditary tendency but occurs sporadically. The diagnosis of SWS is established with neuroimaging techniques such as MRI with contrast, which shows the presence of leptomeningeal malformations in the brain. Treatment of this is symptomatic such as seizures are treated with anti-epileptic medications, ocular symptoms are managed with surgical modalities, and skin manifestations are treated with the laser. Prognosis of SWS is dependent on the age of onset of seizures, the extent of the brain, and dermatological involvement.

Historical Perspective

The term Sturge-Weber syndrome was coined by Professor Hilding Bergstrand in 1935 to acknowledge the work of two physicians, William Allen Sturge, and Parkes Weber. [1] In 1879 William Allen Sturge noted a case of right sided facial lesion, ocular abnormalities, and neurological involvement in a six and half year old female. He later named this facial lesion as a port wine stain. In 1922, Parkes Weber, described the radiogical features of a brain lesion in a twenty-two year old woman with left sided vascular lesion on of her trunk, with right sided congenital spastic hemiplegia.[2]

Classification

Encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis may be classified according to facial and leptomeningeal involvement into three subtypes by using Roach Scale.

Type I: Classic Sturge-Weber syndrome that involves both facial, and leptomeningeal involvement, may have glaucoma.

Type II: Only facial angiomatosis with no CNS involvement, may have glaucoma.

Type III: Only CNS involvement, and no glaucoma.

Pathophysiology and Genetics

The cause of SWS is somatic mosaic mutations in the GNAQ gene. The GNAQ gene is located on the long arm of chromosome number 9, at the position 21.2, and comprise of 7 exons. The function of this gene is to produce a protein called guanine nucleotide-binding protein G-alpha-q, which functions to regulate intracellular signaling pathways to help regulate the structure and functions of blood vessels. The somatic mutation in this gene (mutation that is occurring after conception and which is not inherited) replaces the amino acid arginine with the amino acid glutamine at position 183 in the G-alfa-q protein. This mutation specifically affects the cell responsible for angiogenesis in brain, skin and eyes. Other somatic mutation in GNAQ gene is responsible for the development of uveal melanoma, however, patients with SWS are not at high risk for the development of uveal melanoma.

On gross pathological examination, the leptomeninges looks thickened and the leptomeningeal vessels show dilatations and tortuosities. These vessels in leptomeninges show overexpression of Fibronectin and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors (VEGF).[3]

On microscopic histopathological analysis of brain tissues show, intracranial calcification, gliosis, hypoplastic blood vessels, and loss of neurons. It is hypothesized that the hypoxic injury to the endothelial cells can lead to the breakdown of blood-brain barrier and can cause intracranial calcification. [4]

Clinical Features

Neurological manifestations

SWS is characterized by the formation of leptomeningeal capillary-venous malformation or angioma, which can cause various neurological symptoms such as seizures, stroke, intellectual disabilities, and behavioral issues. Intracranial angiomas occur on the same facial port-wine stain, it usually involves occipital and parietal lobes.[1]

Seizures

Seizures is the most common symptom of SWS seen in 75-90% of patients , and it is often the first presentation. The age of onset of seizures is usually in early childhood, but it can occur at any age. The risk of seizures is high with a bilateral port-wine stain that unilateral port-wine stain.[5] At first, seizures are focal, but later in the course can turn into generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Rarely, a small subgroup of patients can present with infantile spasm and atonic seizures.

Stroke like episodes

Possibly chronic hypoxia-induced injury in leptomeningeal blood vessels leads to stroke-like events. They occur in 25-60% of patients with SWS. These stroke-like episodes occur concurrently with the seizures and can lead to hemiparesis. Hemiparesis usually occur contralateral to the brain lesions. Children are more prone to develop these stroke-like episodes due to repeated falls and minor head injuries.[6].

Cognitive impairment

Cognitive impairment in the form of delayed neuropsychological development occur in 50-60% patients with SWS, and it may range from mild attention deficit to severe deterioration in the mental capacity. Early-onset of seizures is associated with the high risk of developing severe forms of cognitive impairment.[5]. Other behavioral problems associated with SWS are Autism Spectrum Disorder, social communication difficulties. [7]. Adults with normal cognitive function usually have depression, while aggression and self-destructive behavior occur in intellectually impaired adults.[4]

Migraine like headaches

Headaches are very common symptoms of SWS Kossoff et al. reported the headaches can be as debilitating as seizures, the median age of onset of headache was 8. They also reported that the patients with a family history of headaches have an earlier age at onset of headache. [8]

Neuroendocrine problems

Diagnosis

Physical examination

Gallery

Skin

Head

Symptoms

Sturge-Weber syndrome is indicated at birth by seizures accompanied by a large port-wine stain birthmark on the forehead and upper eyelid of one side of the face. The birthmark can vary in color from light pink to deep purple, and is caused by an overabundance of capillaries around the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, just beneath the surface of the face. There is also malformation of blood vessels in the pia mater overlying the brain, on the same side of the head as the birthmark. This causes calcification of tissue and loss of nerve cells in the cerebral cortex. Neurological symptoms include seizures that begin in infancy and may worsen with age. Convulsions usually happen on the side of the body opposite the birthmark, and vary in severity. There may be muscle weakness on the same side. Some children will have developmental delays and mental retardation; most will have glaucoma (increased pressure within the eye), which can be present at birth or develop later. Increased pressure within the eye can cause the eyeball to enlarge and bulge out of its socket (buphthalmos). Sturge-Weber syndrome rarely affects other body organs.

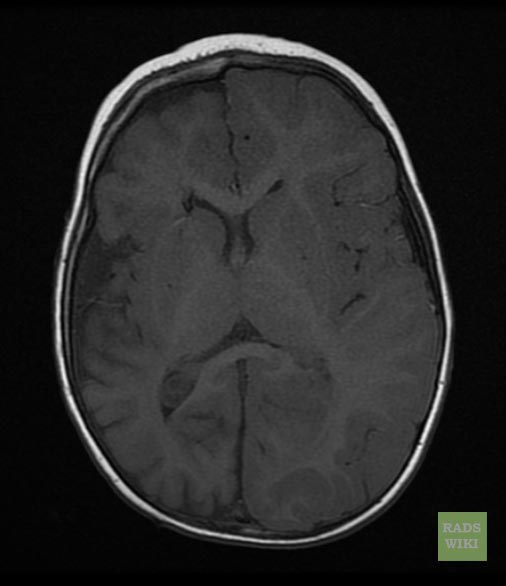

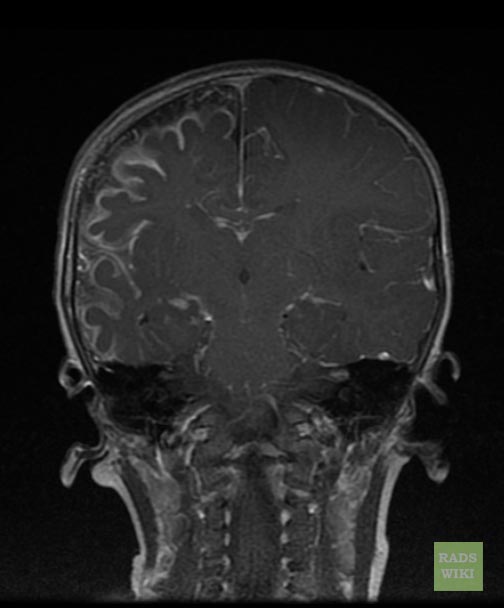

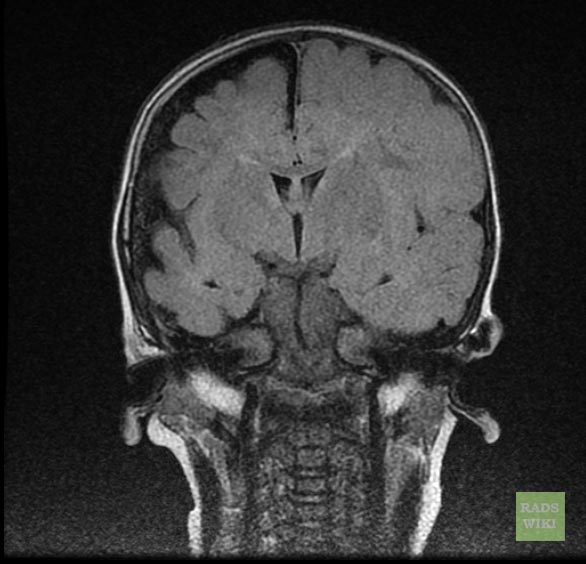

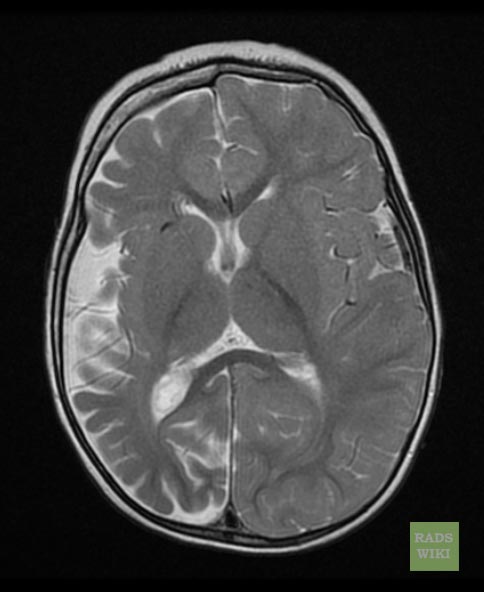

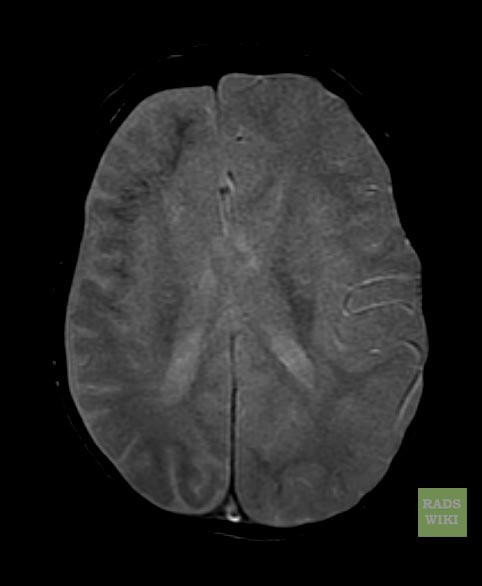

MRI

-

Sturge-Weber syndrome

-

Sturge-Weber syndrome

-

Sturge-Weber syndrome

-

Sturge-Weber syndrome

-

Sturge-Weber syndrome

Treatment

Treatment for Sturge-Weber syndrome is symptomatic. Laser treatment may be used to lighten or remove the birthmark. Anticonvulsant medications may be used to control seizures. Doctors recommend yearly monitoring for glaucoma, and surgery may be performed on more serious cases. Physical therapy should be considered for infants and children with muscle weakness. Educational therapy is often prescribed for those with mental retardation or developmental delays, but there is no complete treatment for the delays. Brain surgery involving removing the portion of the brain that is affected by the disorder can be successful in controlling the seizures experienced so that the patient has only a few seizures that much less intnse than pre-surgery. One of the hospitals that has successfully completed this procedure is Shands at the University of Florida.

Prognosis

Although it is possible for the birthmark and atrophy in the cerebral cortex to be present without symptoms, most infants will develop convulsive seizures during their first year of life. There is a greater likelihood of intellectual impairment when seizures start before the age of 2 and are resistant to treatment.

Eponym

It is named for William Sturge and Frederick Parkes Weber.[9][10][11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sudarsanam A, Ardern-Holmes SL (2014). "Sturge-Weber syndrome: from the past to the present". Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 18 (3): 257–66. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.10.003. PMID 24275166.

- ↑ Weber FP (1922). "RIGHT-SIDED HEMI-HYPOTROPHY RESULTING FROM RIGHT-SIDED CONGENITAL SPASTIC HEMIPLEGIA, WITH A MORBID CONDITION OF THE LEFT SIDE OF THE BRAIN, REVEALED BY RADIOGRAMS". J Neurol Psychopathol. 3 (10): 134–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.s1-3.10.134. PMC 1068054. PMID 21611493.

- ↑ Comati A, Beck H, Halliday W, Snipes GJ, Plate KH, Acker T (2007). "Upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha in leptomeningeal vascular malformations of Sturge-Weber syndrome". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 66 (1): 86–97. doi:10.1097/nen.0b013e31802d9011. PMID 17204940.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Comi AM (2011). "Presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of the neurological features of Sturge-Weber syndrome". Neurologist. 17 (4): 179–84. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e318220c5b6. PMC 4487915. PMID 21712663.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sujansky E, Conradi S (1995). "Sturge-Weber syndrome: age of onset of seizures and glaucoma and the prognosis for affected children". J Child Neurol. 10 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1177/088307389501000113. PMID 7769179.

- ↑ Zolkipli Z, Aylett S, Rankin PM, Neville BG (2007). "Transient exacerbation of hemiplegia following minor head trauma in Sturge-Weber syndrome". Dev Med Child Neurol. 49 (9): 697–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00697.x. PMID 17718827.

- ↑ Gittins S, Steel D, Brunklaus A, Newsom-Davis I, Hawkins C, Aylett SE (2018). "Autism spectrum disorder, social communication difficulties, and developmental comorbidities in Sturge-Weber syndrome". Epilepsy Behav. 88: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.08.006. PMID 30195931.

- ↑ Kossoff EH, Hatfield LA, Ball KL, Comi AM (2005). "Comorbidity of epilepsy and headache in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome". J Child Neurol. 20 (8): 678–82. doi:10.1177/08830738050200080901. PMID 16225815.

- ↑ Template:WhoNamedIt

- ↑ W. A. Sturge. A case of partial epilepsy, apparently due to a lesion of one of the vasomotor centres of the brain. Transactions of the Clinical Society of London, 1879, 12: 162.

- ↑ F. P. Weber. Right-sided hemi-hypertrophy resulting from right-sided congenital spastic hemiplegia, with a morbid condition of the left side of the brain, revealed by radiograms. Journal of Neurology and Psychopathology, London, 1922, 3: 134-139.

Pictures

Template:Phakomatoses and other congenital malformations not elsewhere classified