Baylisascaris infection: Difference between revisions

m (Robot: Changing Category:DiseaseState to Category:Disease) |

m (Bot: Automated text replacement (-{{SIB}} + & -{{EH}} + & -{{EJ}} + & -{{Editor Help}} + & -{{Editor Join}} +)) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{SI}} | {{SI}} | ||

== Overview == | == Overview == | ||

| Line 203: | Line 203: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

{{WH}} | {{WH}} | ||

Revision as of 22:48, 8 August 2012

Overview

Related Key Words and Synonyms:

Raccoon roundworm infection

Epidemiology and Demographics

Baylisascaris, an intestinal raccoon roundworm, can infect a variety of other animals, including humans. The worms develop to maturity in the raccoon intestine, where they produce millions of eggs that are passed in the feces. Released eggs take 2-4 weeks to become infective to other animals and humans. The eggs are resistant to most environmental conditions and with adequate moisture, can survive for years.

Geographic distribution

Raccoons infected with Baylisascaris procyonis appear to be common in the Middle Atlantic, Midwest, and Northeast regions of the United States and are well documented in California and Georgia. Proven human cases have been reported in California, Oregon, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota, with a suspected case in Missouri.

How common is Baylisascaris infection in humans?

Infection is rarely diagnosed. Fever than 25 cases have been diagnosed and reported in the United States as of 2003. However, it is believed that cases are mistakenly diagnosed as other infections or go undiagnosed. Cases have been reported in Oregon, California, Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania. Five of the infected persons died.

How common is Baylisascaris infection in raccoons?

Fairly common. Infected raccoons have been found throughout the United States, mainly in the Midwest, Northeast, middle Atlantic, and West coast. Infection rarely causes symptoms in raccoons. Predator animals, including dogs, may also become infected by eating a smaller animal that has been infected with Baylisascaris.

Raccoon Roundworm Encephalitis --- Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California, 2000

Baylisascaris procyonis (BP), a common roundworm found in the small intestine of raccoons, causes severe or fatal encephalitis (neural larva migrans [NLM]) in a variety of birds and mammals, including humans (1--8). BP also can cause human ocular and visceral larva migrans (1,2,9). Humans become infected with BP by ingesting soil or other materials (e.g., bark or wood chips) contaminated with raccoon feces containing BP eggs (2). Young children are at particular risk for infection as a result of behaviors such as pica and geophagia and placing potentially contaminated fingers and other objects (e.g., toys) into their mouths. This report describes two cases of BP encephalitis in residents of Chicago and Los Angeles and illustrates the importance of reducing exposure to raccoons and their feces in U.S. urban areas.

Chicago

During July 2000, a boy aged 2½ years with a history of iron deficiency anemia and pica was admitted to a Chicago hospital with a low-grade fever of 8 days duration and increasing lethargy, irritability, and ataxia during the 3 days preceding admission. A diagnosis of encephalitis was made based on the clinical presentation and laboratory findings on admission, including peripheral eosinophilia (28% of 21,000 white blood cells/mm3), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) eosinophilic pleocytosis (32% of 80 white blood cells/mm3), and diffuse slow waves on an electroencephalogram. Less than 24 hours after admission, the patient lapsed into a coma with opisthotonus and decerebrate posturing; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed abnormalities in the deep white matter of both cerebellar hemispheres. Other possible causes of encephalitis (e.g., herpes simplex; arboviruses and enteroviruses; lymphocytic choriomeningitis; measles; and bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections [e.g., toxocariasis and cysticercosis]) were excluded based on direct examination, culture, serology, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood and CSF. Antibodies to BP were detected in CSF and serum specimens by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) (6,8) with titers increasing several fold and reaching high levels (1:1,024 in CSF and 1:4,096 in serum specimens) during the 4 weeks following admission. The child was treated with albendazole and corticosteroids, but his condition did not improve. After 4 weeks of hospitalization, he was transferred to a rehabilitation center where he stayed for several months. He then was sent home where he remains profoundly neurologically disabled and in need of continuous nursing care.

Eighteen days before admission, the child's parents had observed that he had dirt on his mouth while playing beneath a cluster of trees in a nearby yard in a Chicago suburb where raccoons are common. A field study conducted in September 2000 revealed several sites of raccoon fecal contamination positive for BP eggs in the yard. Infective BP eggs were recovered from soil and debris at the base of the tree cluster; mice infected with these eggs developed fatal encephalitis as a result of NLM.

Los Angeles

In January 2000, a boy aged 17 years with an 8-year history of severe developmental disabilities and geophagia was admitted to a Los Angeles hospital comatose and with generalized hypertonia and hyperreflexia. His mouth was tightly clenched, his eyes wandered rapidly, and he responded only to painful stimuli. Two days before admission, he had a low-grade fever, drowsiness, and problems with coordination. Laboratory findings on admission included peripheral eosinophilia (15% of 15,900 white blood cells/mm3) and a CSF eosinophilic pleocytosis (37% of 19 white blood cells/mm3). He was treated with antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antiparasitic (albendazole), and antiinflammatory agents, but his condition did not improve. Tests on CSF and blood failed to identify an infectious agent. On examination by a pathologist, a brain biopsy revealed sections of a nematode consistent with Baylisascaris species. Baylisascaris IFA tested strongly positive with titers of 1:256 in CSF and 1:4,096 in serum specimens. The patient's condition deteriorated and he had progressive, deep white matter abnormalities of the brain on MRI. After a 2-month hospitalization, he was transferred to a long-term--care facility where he remained comatose until he died a year later.

The patient had resided in a group home for developmentally handicapped adolescents and adults in Los Angeles County. In February 2000, a field study conducted in the yard in which the patient regularly played revealed several sites containing raccoon feces; a sample of sandbox soil was positive for BP eggs. Multiple sites in the adjoining yard, to which he also had access, contained raccoon feces with BP eggs.

Risk Factors

Anyone who is exposed to environments where raccoons live is potentially at risk. Young children or developmentally disabled persons are at highest risk for infection when they spend time outdoors and may put contaminated fingers, soil, or objects into their mouths. Hunters, trappers, taxidermists, and wildlife handlers may also be at increased risk if they have contact with raccoons or raccoon habitats.

Screening

Pathophysiology & Etiology

Etiologic agent:

Human baylisascariasis is caused by larvae of Baylisascaris procyonis, an intestinal nematode of raccoons.

Life cycle:

Baylisascaris procyonis completes its life cycle in raccoons (Procyon lotor), with humans acquiring the infection as accidental hosts. Following ingestion by many different hosts (over 50 species of birds and mammals, especially rodents, have been identified as intermediate hosts) eggs hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall and migrate into various tissues, where they encyst. The life cycle is completed when raccoons eat these hosts. The larvae develop into egg-laying adult worms in the small intestine and eggs are eliminated in raccoon feces. People become accidentally infected when they ingest infective eggs from the environment; typically this occurs in young children playing in the dirt. After ingestion, the eggs hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall and migrate to a wide variety of tissues (liver, heart, lungs, brain, eyes), and cause visceral (VLM) and ocular (OLM) larva migrans syndromes, similar to toxocariasis. In contrast to Toxocara larvae, Baylisascaris larvae continue to grow during their time in the human host. Tissue damage and the signs and symptoms of baylisascariasis are often severe because of the size of Baylisascaris larvae, their tendency to wander widely, and the fact that they do not readily die. Tissue damage and the signs and symptoms of baylisascariasis are often severe.

Molecular Biology

Genetics

Natural History

Diagnosis

Infection is difficult to diagnose and often is made by ruling out other infections that cause similar symptoms. Information on diagnosis and testing can be obtained through DPDx or your local health department.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

Human infections are difficult to diagnose, and often the diagnosis is by exclusion of other causes. Results from complete blood count (CBC) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination would be consistent with parasitic infection, but tend to be nonspecific. Examination of tissue biopsies can be extremely helpful if a section of larva is contained, but removing an appropriate piece of tissue where the larva is actually present can be problematic. Ocular examinations revealing a migrating larva, larval tracks, or lesions consistent with a nematode larva are often the most significant clue to infection with Baylisascaris. Serologic testing can be extremely helpful in suspected cases; however, tests are not routinely in use nor widely available.

Differential Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

Symptoms of infection depend on how many eggs are ingested and where in the body the larvae migrate (travel to). Once inside the body, eggs hatch into larvae and cause disease when they travel through the liver, brain, spinal cord, or other organs. Ingesting a few eggs may cause few or no symptoms, while ingesting large numbers of eggs may lead to serious symptoms. Symptoms of infection may take a week or so to develop.

Symptoms include

- Nausea

- Tiredness

- Liver enlargement

- Loss of coordination

- Lack of attention to people and surroundings

- Loss of muscle control

- Coma

- Blindness

Other animals (except raccoons) infected with Baylisascaris can develop similar symptoms, or may die as a result of infection.

Physical Examination

Appearance of the Patient

Vital Signs

Skin

Eyes

Ear Nose and Throat

Heart

Lungs

Abdomen

Extremities

Neurologic

Other

Laboratory Findings

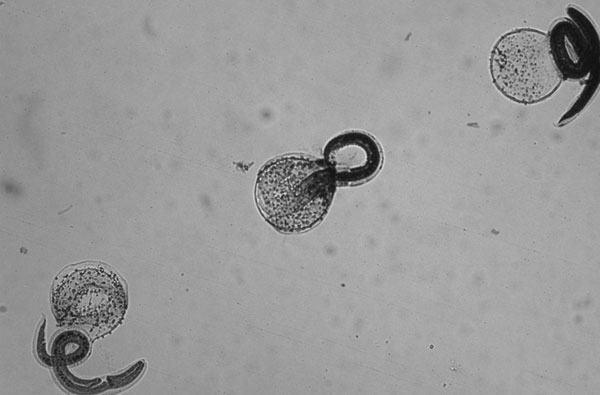

Microscopy:

A: Unembryonated eggs of Baylisascaris procyonis. These eggs are thick-shelled and usually a little oval in shape. Size of these eggs is 80-85 microns by 65-70 microns. The eggs of B. procyonis have a similar morphological appearance as fertile eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides with size (A. lumbricoides eggs being 55 to 75 microns by 35 to 50 microns) as the most evident distinguishing characteristic. Unembryonated eggs of B. procyonis are passed only in the feces of raccoons and skunks (and sometimes other carnivorous animals) onto the soil, after which they further develop to the infective second stage larva in about 2 to 3 weeks. Humans become infected by accidentally ingesting infective eggs from soil, water, hands, food or other objects contaminated with raccoon or skunk feces. As in Toxocara infections, eggs are not a diagnostic finding since they are not excreted in human feces.

Electrolyte and Biomarker Studies

Electrocardiogram

Chest X Ray

MRI and CT

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

Other Imaging Findings

Other Diagnostic Studies

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

Treatment

Early treatment might reduce serious damage caused by the infection. Should you suspect you may have ingested raccoon feces, seek immediate medical attention.

Pharmacotherapy

Acute Pharmacotherapies

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

Primary Prevention

How can I prevent infection in myself, my children, or my neighbors?

- Avoid direct contact with raccoons — especially their feces. Do not keep, feed, or adopt raccoons as pets! Raccoons are wild animals.

- Discourage raccoons from living in and around your home or parks by:

- preventing access to food

- closing off access to attics and basements

- keeping sand boxes covered at all times, (becomes a latrine)

- removing fish ponds — they eat the fish and drink the water

- eliminating all water sources

- removing bird feeders

- keeping trash containers tightly closed

- clearing brush so raccoons are not likely to make a den on your property

- Stay away from areas and materials that might be contaminated by raccoon feces. Raccoons typically defecate at the base of or in raised forks of trees, or on raised horizontal surfaces such as fallen logs, stumps, or large rocks. Raccoon feces also can be found on woodpiles, decks, rooftops, and in attics, garages, and haylofts. Feces usually are dark and tubular, have a pungent odor (usually worse than dog or cat feces), and often contain undigested seeds or other food items.

- To eliminate eggs, raccoon feces and material contaminated with raccoon feces should be removed carefully and burned, buried, or sent to a landfill. Care should be taken to avoid contaminating hands and clothes. Treat decks, patios, and other surfaces with boiling water or a propane flame-gun. (Exercise proper precautions!) Newly deposited eggs take at least 2-4 weeks to become infective. Prompt removal and destruction of raccoon feces will reduce risk for exposure and possible infection.

- Contact your local animal control office for further assistance.

Secondary Prevention

Cost-Effectiveness of Therapy

Future or Investigational Therapies

"The Way I Like To Do It ..." Tips and Tricks From Clinicians Around The World

Suggested Revisions to the Current Guidelines

References

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baylisascaris

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/baylisascaris/default.htm

- http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5051a1.htm

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D.

Initial content for this page in some instances came from Wikipedia

List of contributors:

Pilar Almonacid