Coronary artery anomalies

|

Coronary Angiography | |

|

General Principles | |

|---|---|

|

Anatomy & Projection Angles | |

|

Normal Anatomy | |

|

Anatomic Variants | |

|

Projection Angles | |

|

Epicardial Flow & Myocardial Perfusion | |

|

Epicardial Flow | |

|

Myocardial Perfusion | |

|

Lesion Complexity | |

|

ACC/AHA Lesion-Specific Classification of the Primary Target Stenosis | |

|

Lesion Morphology | |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]; Mohamed Moubarak, M.D. [3]

Overview

The coronary arteries are usually perpendicular to the aortic wall and they are radially arranged relative to the center of the aorta. The ostia may be rounding, oval, or elliptical, and the position of the ostium does not appear to affect the flow through it.

Classification

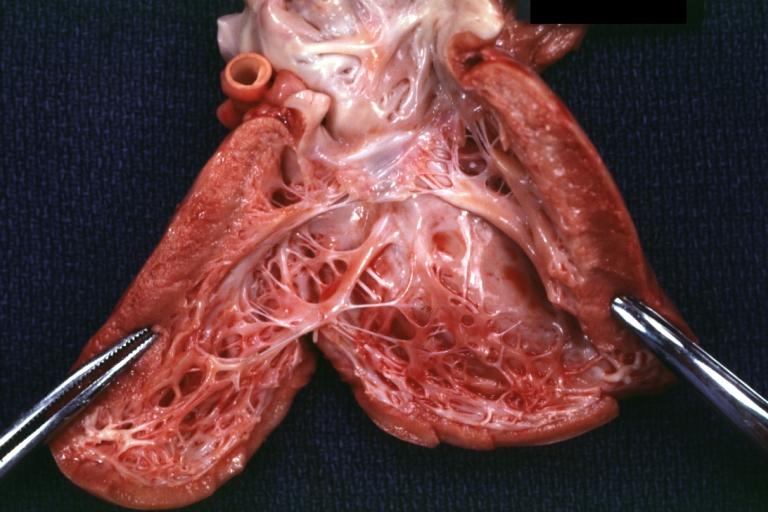

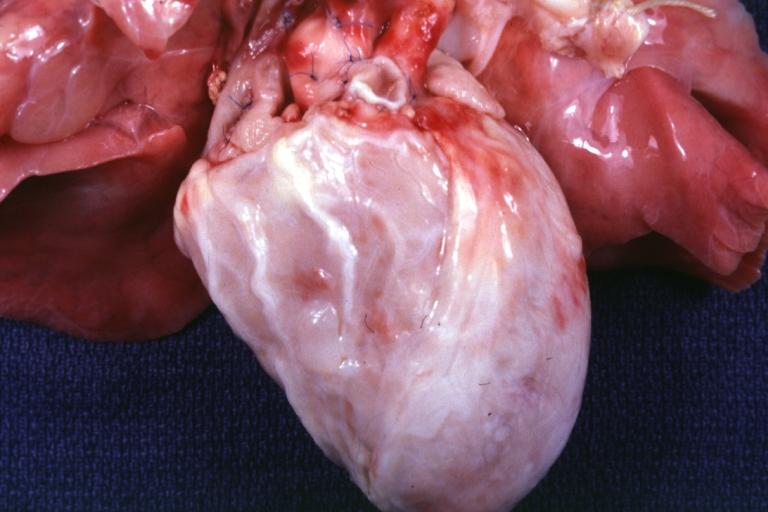

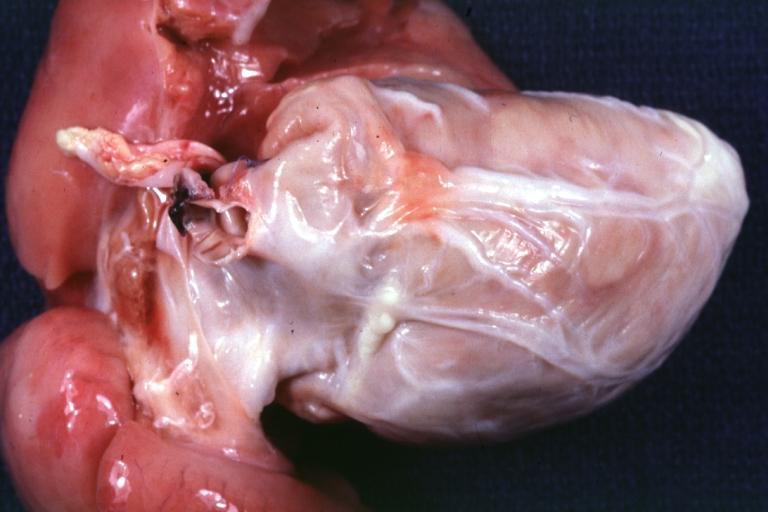

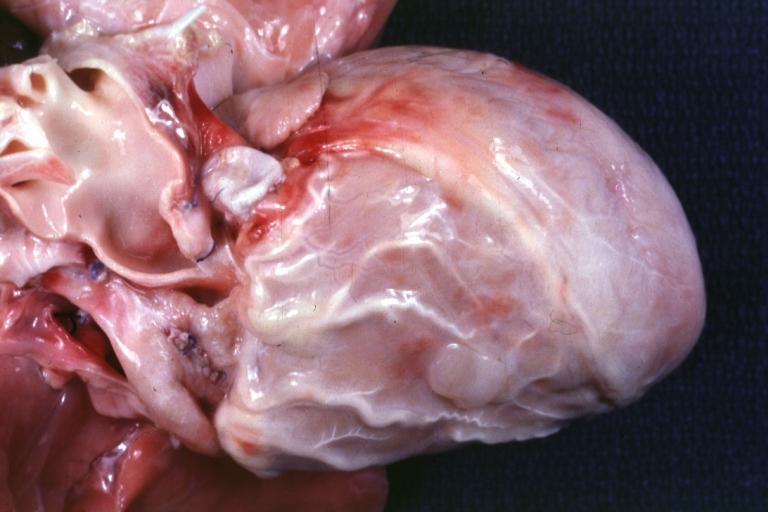

Anomalous Pulmonary Origin of the Coronary Arteries

Anomalous Pulmonary Origin of the Coronary Arteries (APOCA) is characterized by the origin of a coronary artery from the pulmonary artery.[1] Left coronary artery is the most common anomaly seen arising from pulmonary artery (ALCAPA),[2] in which angiography shows the absence of left coronary ostium normal flow from the left aortic sinus. Other anomalies of the coronary arteries origin include:[3]

- Left circumflex artery (Cx) arising from pulmonary artery posterior facing sinus

- Left anterior descending artery (LAD) arising from pulmonary artery posterior facing sinus

- Right coronary artery (RCA) arising from pulmonary artery anterior right facing sinus (ARCAPA):

- Rare, only about 10% of left main coronary artery originated from the pulmonary artery. [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

- It is almost always found as an incidental autopsy finding of sudden death, and if diagnosed before death it has been associated with:

- Symptoms of myocardial ischemia

- Syncope

- Cardiomyopathy

- Coronary artery arising from other locations outside pulmonary facing sinuses e.g. anterior left sinus, pulmonary trunk, or pulmonary branch

Mortality rate in the first year of life has been reported to be 95% in untreated cases with poor collateral network.[10]

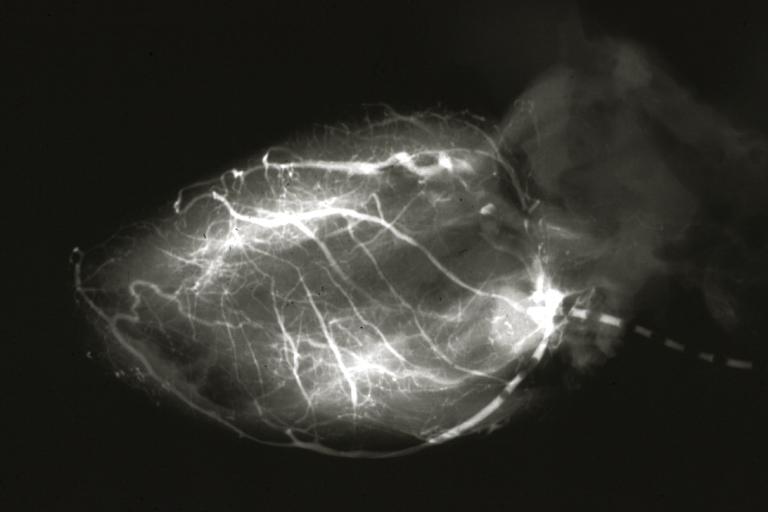

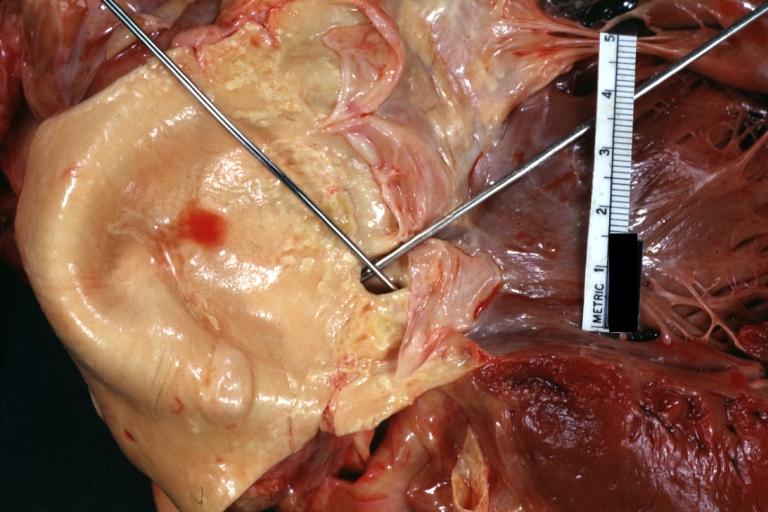

Courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD

Anomalous Coronary Artery From the Opposite Sinus

It is an improper site of coronary origin, in some cases in involve the origin of two coronaries from the same ostium.[3] The anomalous coronary origin leads to different anomalous course for the coronary arteries, which can be detected by angiography and they are as follow:

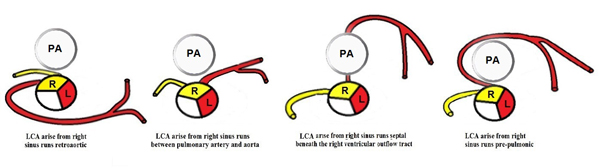

LCA that arises from right anterior sinus

LCA runs in a different courses when arise from right sinus of valsalva, and it includes a septal, anterior, interarterial, and posterior course. The anomalous courses can be more specified as follow:[3][11]

- Posterior atrioventricular groove

- Retroaortic

- Between aorta and pulmonary artery

- Intraseptal

- Anterior to pulmonary artery

- Posteroanterior interventricular groove

|

|

|

Courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD

LAD that arises from right anterior sinus

When LAD arises from the right anterior sinus, it may run in a similar course as LCA which include:[3]

- Between aorta and pulmonary artery

- Intraseptal

- Anterior to pulmonary artery

- Posteroanterior interventricular groove

LCx artery that arises from right anterior sinus

LCx artery when arise from right sinus of valsalva, it may run in the posterior atrioventricular groove, or follow a retroaortic course.[3]

RCA that arises from left anterior sinus

When RCA arise from the left sinus, it follows the same anomalous courses as the LAD when arise from the the right sinus of Valsalva, with the most common course is the interarterial.[3][12]

Coronary artery fistulas are rare findings, defines as any abnormal communication through which coronary artery blood is shunted into:

- Any of the cardiac chambers

- The besian veins that empty into the cardiac chambers

- The coronary sinus

- The SVC

- The pulmonary veins

- The mediastinal vessels

It is identified in 10 (0.05%) of 18,272 diagnostic cardiac catheterizations. The number, origin, and course of the coronary arteries is otherwise normal.[13][14]

Congenital Coronary Stenosis or Atresia

Congenital coronary stenosis can be associated with other congenital diseases (e.g. supravalvular aortic stenosis, calcific coronary sclerosis, or rubella syndrome), or one of the intrinsic coronary arterial anatomy anomalies, which may involve left coronary artery, left anterior descending artery, right coronary artery, and left circumflex artery.[15]

Other intrinsic coronary arterial anatomy anomalies include:[3]

- Coronary ostial dimple

- Coronary ectasia or aneurysm

- Absent coronary artery

- Coronary hypoplasia

- Intramural coronary artery (muscular bridge)

- Subendocardial coronary course

- Coronary crossing

- Anomalous origination of posterior descending artery from the anterior descending branch or a septal penetrating branch

- Split RCA

- Split LAD

- Ectopic origination of first septal branch

Myocardial bridge is defined as a segment of a major coronary epicardial artery that "tunnels" or passes intramurally through the myocardium beneath the muscle bridge during systole.[16][17] Myocardial bridges are generally located in the distribution of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and its diagonal branches. It has been associated with angina, arrhythmia, depressed left ventricular function, myocardial stunning, early death after cardiac transplantation, and sudden death.[16][18]

On angiography, the bridged segment appears of normal caliber during diastole, and abruptly narrows with systole. Shown below is an animated image depicting myocardial bridge, and two static images of the same case depicting myocardial bridge. Outlined with yellow in the image on the left is the part of the coronary artery during diastole. This same part of the coronary artery is outlined in yellow in the image on the right during systole; note that this outlined part is narrowed compared to its shape during diastole.

High Anterior Origin of the Right Coronary Artery

A superior origin of the RCA above the sinotubular ridge, although it is found commonly, it has no hemodynamic significance. This case is suspected during catheterization when it fails to engage the ostium of the RCA, and injection of contrast medium into the right sinus of Valsalva may reveal the anomalous origin.[19]

2008 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

Evaluation and Surgical Intervention (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. Any patient with CHD who has had coronary artery manipulation should be evaluated for coronary artery patency, function, and anatomic integrity at least once in adulthood. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”2. Surgeons with training and expertise in CHD should perform operations for the treatment of coronary artery anomalies.(Level of Evidence: C)" |

Coronary Anomalies Associated With Supravalvular Aortic Stenosis (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. Adults with a history or presence of SupraAS should be screened every 1 or 2 years for myocardial ischemia. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "2. Interventions for coronary artery obstruction in patients with SupraAS should be performed in ACHD centers with demonstrated expertise in the interventional management of these patients. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

Coronary Anomalies Associated With Tetralogy of Fallot (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. Coronary artery anatomy should be determined before any intervention for RV outflow. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

Coronary Anomalies Associated With Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries After Arterial Switch Operation (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. Adult survivors with dextro-TGA (d-TGA) after arterial switch operation (ASO) should have noninvasive ischemia testing every 3 to 5 years. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

Congenital Coronary Anomalies of Ectopic Arterial Origin (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. The evaluation of individuals who have survived unexplained aborted sudden cardiac death or with unexplained life-threateningarrhythmia, coronary ischemic symptoms, or LV dysfunction should include assessment of coronary artery origins and course. (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| ”2. CT or magnetic resonance angiography is useful as the initial screening method in centers with expertise in such imaging.(Level of Evidence: B)" |

| ”3. Surgical coronary revascularization should be performed in patients with any of the following: |

| a. Anomalous left main coronary artery coursing between the aorta and pulmonary artery. (Level of Evidence: B) |

| b. Documented coronary ischemia due to coronary compression (when coursing between the great arteries or in intramural fashion). (Level of Evidence: B) |

| c. Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery between aorta and pulmonary artery with evidence of ischemia. (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| Class IIa |

| "1. Surgical coronary revascularization can be beneficial in the setting of documented vascular wall hypoplasia, coronary compression, or documented obstruction to coronary flow, regardless of inability to document coronary ischemia. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”2. Delineation of potential mechanisms of flow restriction via intravascular ultrasound can be beneficial in patients with documented anomalous coronary artery origin from the opposite sinus. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| Class IIb |

| "1. Surgical coronary revascularization may be reasonable in patients with anomalous left anterior descending coronary artery coursing between the aorta and pulmonary artery. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

Anomalous Left Coronary Artery From the Pulmonary Artery (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. In patients with an anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA), reconstruction of a dual coronary artery supply should be performed. The surgery should be performed by surgeons with training and expertise in CHD at centers with expertise in the management of anomalous coronary artery origins. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”2. For adult survivors of ALCAPA repair, clinical evaluation with echocardiography and noninvasive stress testing is indicated every 3 to 5 years. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

Coronary Arteriovenous Fistula (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. If a continuous murmur is present, its origin should be defined either by echocardiography, MRI, CT angiography, or cardiac catheterization. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”2. A large coronary arteriovenous fistula (CAVF), regardless of symptomatology, should be closed via either a transcatheter or surgical route after delineation of its course and its potential to fully obliterate the fistula. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”3. A small to moderate CAVF in the presence of documented myocardial ischemia, arrhythmia, otherwise unexplained ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction or enlargement, or endarteritis should be closed via either a transcatheter or surgical approach after delineation of its course and its potential to fully obliterate the fistula. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| Class III |

| "1. Patients with small, asymptomatic CAVF should not undergo closure of CAVF. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| Class IIa |

| "1. Clinical follow-up with echocardiography every 3 to 5 years can be useful for patients with small, asymptomatic CAVF to exclude development of symptoms or arrhythmias or progression of size or chamber enlargement that might alter management. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

Management Strategies for CAVF(DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| Class I |

| "1. Surgeons with training and expertise in CHD should perform operations for management of patients with CAVF. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”2. Transcatheter closure of CAVF should be performed only in centers with expertise in such procedures. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| ”3. Transcatheter delineation of CAVF course and access to distal drainage should be performed in all patients with audible continuousmurmur and recognition of CAVF. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

References

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ Hofmeyr, L.; Moolman, J.; Brice, E.; Weich, H. (2009). "An unusual presentation of an anomalous left coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) in an adult: anterior papillary muscle rupture causing severe mitral regurgitation". Echocardiography. 26 (4): 474–7. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00815.x. PMID 19054023. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Coronary Artery Anomalies". Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Coe JY, Radley-Smith R, Yacoub M. Clinical and hemodynamic significance of anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1982;30:84-7.

- ↑ Fontana RS, Edwards JE. Congenital Cardiac Disease: A Review of 357 Cases Studied Pathologically. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1962.

- ↑ Ogden JA. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol 1970;25:474-79.

- ↑ Neufeld HN, Schneeweiss A. Coronary Artery Disease in Infants and Children. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1983.

- ↑ Roberts WC. Major anomalies of coronary arterial origin seen in adulthood. Am Heart J 1986; 111: 941-63.

- ↑ Yao CT, Wang JN, Yeh CN, et al. Isolated anomalous origin of right coronary artery from the main pulmonary artery. J Card Surg 2005;20:487-89.

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ Cebi N, Schulze-Waltrup N, Frömke J, Scheffold T, Heuer H (2008). "Congenital coronary artery fistulas in adults: concomitant pathologies and treatment". Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 24 (4): 349–55. doi:10.1007/s10554-007-9277-x. PMID 17965946.

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Alegria JR, Herrmann J, Holmes DR, Lerman A, Rihal CS (2005). "Myocardial bridging". European Heart Journal. 26 (12): 1159–68. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi203. PMID 15764618. Retrieved 2012-07-01. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Möhlenkamp S, Hort W, Ge J, Erbel R (2002). "Update on myocardial bridging". Circulation. 106 (20): 2616–22. PMID 12427660. Retrieved 2012-07-01. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Ishikawa Y, Akasaka Y, Suzuki K, Fujiwara M, Ogawa T, Yamazaki K; et al. (2009). "Anatomic properties of myocardial bridge predisposing to myocardial infarction". Circulation. 120 (5): 376–83. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.820720. PMID 19620504.

- ↑ Braunwald, Eugene; Bonow, Robert O. (2012). Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicin. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0398-6.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 20.8 Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA; et al. (2008). "ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". J Am Coll Cardiol. 52 (23): e1–121. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.001. PMID 19038677.