Thalidomide

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 55% and 66% for the (+)-R and (–)-S enantiomers, respectively |

| Elimination half-life | mean ranges from approximately 5 to 7 hours following a single dose; not altered with multiple doses |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| E number | {{#property:P628}} |

| ECHA InfoCard | {{#property:P2566}}Lua error in Module:EditAtWikidata at line 36: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H10N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 258.23 g/mol |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Thalidomide |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Thalidomide Most cited articles on Thalidomide |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Thalidomide |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Thalidomide at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Thalidomide at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Thalidomide

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Thalidomide Discussion groups on Thalidomide Patient Handouts on Thalidomide Directions to Hospitals Treating Thalidomide Risk calculators and risk factors for Thalidomide

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Thalidomide |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Thalidomide is a sedative-hypnotic, and multiple myeloma medication. The drug is a potent teratogen in rats, rabbits, non-human primates and humans: this means that severe birth defects may result if the drug is taken during pregnancy [1].

Thalidomide, 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione, was developed by German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal. It was sold from 1957 to 1961 in almost 50 countries under at least 40 names, including Distaval, Talimol, Nibrol, Sedimide, Quietoplex, Contergan, Neurosedyn, and Softenon. Thalidomide was chiefly sold and prescribed during the late 1950s and early 1960s to pregnant women, as an antiemetic to combat morning sickness and as an aid to help them sleep. Before its release, inadequate tests were performed to assess the drug's safety, with catastrophic results for the children of women who had taken thalidomide during their pregnancies.

From 1956 to 1962, approximately 10,000 children were born with severe malformities, including phocomelia, because their mothers had taken thalidomide during pregnancy.[2] In 1962, in reaction to the tragedy, the United States Congress enacted laws requiring tests for safety during pregnancy before a drug can receive approval for sale in the U.S.[3] Other countries enacted similar legislation, and thalidomide was not prescribed or sold for decades.

Researchers, however, continued to work with the drug. Soon after its banishment, an Israeli doctor discovered anti-inflammatory effects of thalidomide and began to look for uses of the medication despite its teratogenic effects. He found that patients with erythema nodosum leprosum, a painful skin condition associated with leprosy, experienced relief of their pain by taking thalidomide. Further work conducted in 1991 by Dr. Gilla Kaplan at Rockefeller University in New York City showed that thalidomide worked in leprosy by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor alpha. [4] Kaplan partnered with Celgene Corporation to further develop the potential for thalidomide. Subsequent research has shown that it is effective in multiple myeloma, and it was approved by the FDA for use in this malignancy. The FDA has also since approved the drug's use in the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum. There are studies underway to determine the drug's effects on arachnoiditis and several types of cancers. However, physicians and patients alike must go through a special process to prescribe and receive thalidomide (S.T.E.P.S and RevAssist) to ensure no more children are born with birth defects traceable to the medication. Celgene Corporation has also developed analogues to thalidomide, such as lenalidomide, that are substantially more powerful and have fewer side effects - except for greater myelosuppression.[5]

History

A German pharmaceutical company, Chemie Grünenthal at Stolberg, synthesized thalidomide in West Germany in 1953. It had accidentally been discovered during a search for cheap antibiotics, but was soon marketed with little evidence as a sedative.[6]

Thalidomide today

FDA approval

On July 16, 1998, the FDA approved the use of thalidomide for the treatment of lesions associated with erythema nodosum leprosum. Because of thalidomide’s potential for causing birth defects, the distribution of thalidomide was permitted only under tightly controlled conditions. The FDA required that Celgene Corporation, which planned to market thalidomide under the brand name Thalomid, to establish a System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (S.T.E.P.S) oversight program. The S.T.E.P.S program includes limiting prescription and dispensing rights only to authorized prescribers and pharmacies, extensive patient education about the risks associated with thalidomide, periodic pregnancy tests, and a patient registry. [7]

"On May 26, 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval for thalidomide (Thalomid, Celgene Corporation) in combination with dexamethasone for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients." [8] The FDA approval came seven years after the first reports of efficacy in the medical literature[9] and Celgene took advantage of "off-label" marketing opportunities to promote the drug in advance of its FDA approval for the myeloma indication. Thalomid, as the drug is commercially known, sold over $300 million per year, while only approved for leprosy. [10]

Thalidomide was and, as of 2006, still is an important advance in the treatment of multiple myeloma, ever since news of its efficacy appeared in the Desikan et al. report.[9] The drug has some bothersome side effects such as neuropathy, constipation and fatigue, but is likely more effective than standard chemotherapy for multiple myeloma. Thalidomide, along with another new drug, bortezomib, is changing multiple myeloma treatment, such that stem cell transplants may no longer be the standard treatment for this incurable malignancy.

Possible indications

Research on thalidomide slowed in the 1960s, but never stopped. At least one university in the United States pursues thalidomide research, even though performed by only one tenured professor. The medication is an example of how potentially dangerous compounds can be used therapeutically with appropriate precautions and procedures.

In 1964 Israeli physician Jacob Sheskin was trying to help a critically ill French patient with erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a painful complication of leprosy. He searched his small hospital for anything to help his patient stop aching long enough to sleep. He found a bottle of thalidomide tablets, and remembered that it had been effective in helping mentally ill patients sleep, and also that it was banned. Sheskin administered two tablets of thalidomide, and the patient slept for hours, and was able to get out of bed without aid upon awakening. The result was followed by more favorable experiences, and followed by a clinical trial. Dr. Sheskin's drug of last resort revolutionized the care of leprosy, and led to the closing of most leprosy hospitals.[6]

Serious infections including sepsis and tuberculosis cause the level of Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) to rise. TNFα is a chemical mediator in the body, and it may enhance the wasting process in cancer patients as well. Thalidomide may reduce the levels of TNFα, and it is possible that the drug's effect on ENL is caused by this mechanism.[3]

Thalidomide also has potent anti-inflammatory effects that may help ENL patients. In July 1998, the FDA approved the application of Celgene to distribute thalidomide under the brand name Thalomid for treatment of ENL. Pharmion Corporation, who licensed the rights to market Thalidomide in Europe, Australia and various other territories from Celgene, received approval for its use against multiple myeloma in Australia and New Zealand in 2003.[11] Thalomid, in conjunction with dexamethasone, is now standard therapy for multiple myeloma.

Thalidomide also inhibits the growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), which may be useful in treating macular degeneration and other diseases. This effect helps AIDS patients with Kaposi's sarcoma, although there are better and cheaper drugs to treat the condition. Thalidomide may be able to fight painful, debilitating aphthous lesions in the mouth and esophagus of AIDS patients which prevent them from eating. The FDA formed a Thalidomide Working Group in 1994 to provide consistency between its divisions, with particular emphasis on safety monitoring. The agency also imposed severe restrictions on the distribution of Thalomid through the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS) program.[3]

Thalidomide is also being investigated for treating symptoms of prostate cancer, glioblastoma, lymphoma, arachnoiditis, Behçet's disease, and Crohn's disease. In a small trial, Australian researchers found thalidomide sparked a doubling of the number of T cells in patients, allowing the patients' own immune system to attack cancer cells.

On October 5, 2007, Thierry Facon, specialist in blood diseases at Lille University, France who led a research, stated that: "The main message is the addition of thalidomide is able to improve survival. Elderly patients with an aggressive form of blood cancer lived about 20 months longer when given the drug thalidomide as part of their treatment." The drug also slowed the spread of myeloma and had also been approved to treat leprosy.[12]

Teratogenic mechanism

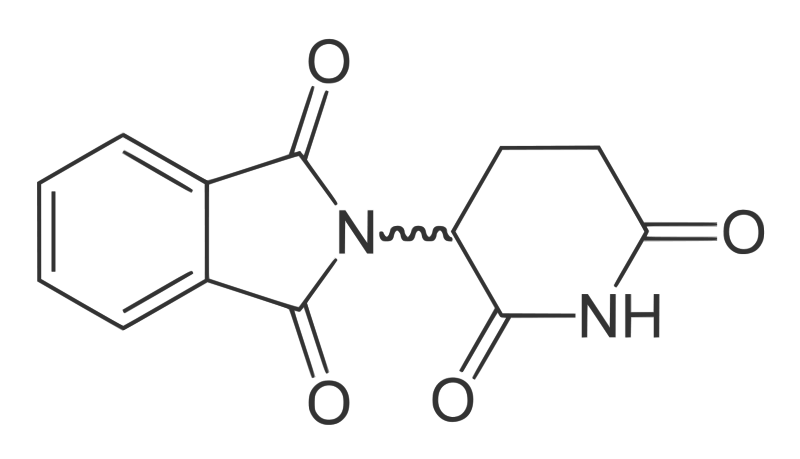

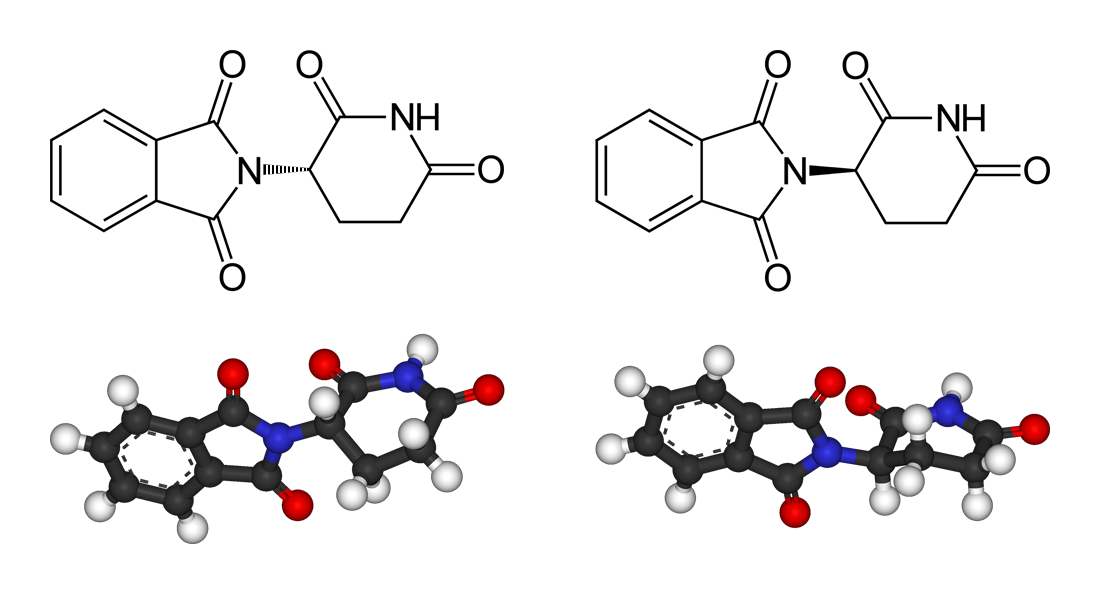

Left: (S)-thalidomide

Right: (R)-thalidomide

Thalidomide is racemic – it contains both left- and right-handed isomers in equal amounts. The (R) enantiomer is effective against morning sickness. The (S) is teratogenic and causes birth defects. The enantiomers can interconvert in vivo – that is, if a human is given pure (R)-thalidomide or (S)-thalidomide, both isomers can be found in the serum – therefore, administering only one enantiomer will not prevent the teratogenic effect in humans. The mechanism of its biological action is being debated, with current literature that suggests that it intercalates into DNA in G-C rich regions.

Other side effects

Apart from its infamous tendency to induce birth defects and peripheral neuropathy, the main side effects of thalidomide include fatigue and constipation. It also is associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis especially when combined with dexamethasone, as it is for treatment of multiple myeloma. High doses can lead to pulmonary edema, atelectasis, aspiration pneumonia and refractory hypotension. In multiple myeloma patients, concomitant use with zoledronic acid may lead to increased incidence of renal dysfunction.

Thalidomide analogs

The exploration of the antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory activities of thalidomide has led to the study and creation of thalidomide analogs. In 2005, Celgene received FDA approval for lenalidomide (Revlimid) as the first commercially useful derivative. Revlimid is only available in a restricted distribution setting to avoid its use during pregnancy. Further studies are conducted to find safer compounds with useful qualities. Another analog, Actimid (CC-4047), is in the clinical trial phase.[13] These thalidomide analogs can be used to treat different diseases, or used in a regimen to fight two conditions.

References

- ↑ http://drugsafetysite.com/thalidomide

- ↑ Bren, Linda (2001-02-28). "Frances Oldham Kelsey: FDA Medical Reviewer Leaves Her Mark on History". FDA Consumer. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2006-09-21. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Burkholz, Herbert (1997-09-01). "Giving Thalidomide a Second Chance". FDA Consumer. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2006-09-21. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Gilla Kaplan "Profile of Gilla Kaplan, findingDulcinea" January 11, 2008

- ↑ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/562417_3

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Silverman, MD, William (2002-04-22). "The Schizophrenic Career of a "Monster Drug"". Pediatrics. 110 (2): 404–406. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, July 16, 1998

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/cder/Offices/OODP/whatsnew/thalidomide.htm

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Desikan, R (1999). "Activity of thalidomide (THAL) in multiple myeloma (MM) confirmed in 180 patients with advanced disease". Blood. 94 (Suppl. 1): 603a–603a. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ http://www.publicintegrity.org/rx/report.aspx?aid=722

- ↑ Rouhi, Maureen. "Thalidomide". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ Reuters, Thalidomide helps elderly cancer patients: study

- ↑ http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/search?term=Actimid&submit=Search

Further reading

- Stephens, Trent (2001-12-24). Dark Remedy: The Impact of Thalidomide and Its Revival as a Vital Medicine. Perseus. ISBN 0-7382-0590-7. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Knightley, Phillip (1979). Suffer The Children: The Story of Thalidomide. New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-68114-8. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help)

External links

- Thalidomide product monograph (Needs registration)

- Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation article on Thalidomide

- International Myeloma Foundation article on Thalidomide

- Thalidomide — Annotated List of Links (covering English and German pages)

- WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter No. 2, 2003 - See page 11, Feature Article

- Grünenthal GmbH - Thalidomide

- Celgene website on Thalomid

- The Return of Thalidomide - BBC

- CBC Digital Archives – Thalidomide: Bitter Pills, Broken Promises

- Thalidomide UK

- The Thalidomide Trust

- "The Big Pitch: How would you conduct a campaign for the new Thalidomide Drugs?"

ar:ثاليدومايد ca:Talidomida cs:Thalidomid da:Thalidomid de:Thalidomid eo:Talidomido ko:탈리도마이드 it:Talidomide he:תלידומיד nl:Thalidomide no:Thalidomid simple:Thalidomide sk:Talidomid sl:Talidomid fi:Talidomidi sv:Neurosedyn uk:Талідомід

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: dates

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- E number from Wikidata

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Teratogens

- Carcinogens

- Medical disasters

- Leprosy

- Withdrawn drugs

- Imides