Supraventricular tachycardia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 22:01, 23 January 2009

| Supraventricular tachycardia | |

| ICD-10 | I47.1 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 427.89 |

| MeSH | D013617 |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Supraventricular tachycardia further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

A supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is a tachycardia or rapid rhythm of the heart in which the origin of the electrical signal is either the atria or the AV node. These rhythms, by definition, are either initiated or maintained by the atria or the AV node. This is in contrast to ventricular tachycardias, which are rapid rhythms that originate from the ventricles of the heart, that is, below the atria or AV node.

- The most frequently seen supraventricular tachycardia is atrial fibrillation

- Can be irregular or regular

Symptoms

Symptoms can come on suddenly and may go away without treatment. They can last a few minutes or as long as 1-2 days. The rapid beating of the heart during SVT can make the heart a less effective pump so that the cardiac output is decreased and the blood pressure drops. The following symptoms are typical with a rapid pulse of 140-250 beats per minute:

- Palpitations - The sensation of the heart racing, fluttering or pounding strongly in the chest or the carotid arteries

- Dizziness, or lightheadedness (near-faint), or fainting

- Shortness of breath

- Anxiety

- Chest pain or sensation of tightness

- Weakness in legs

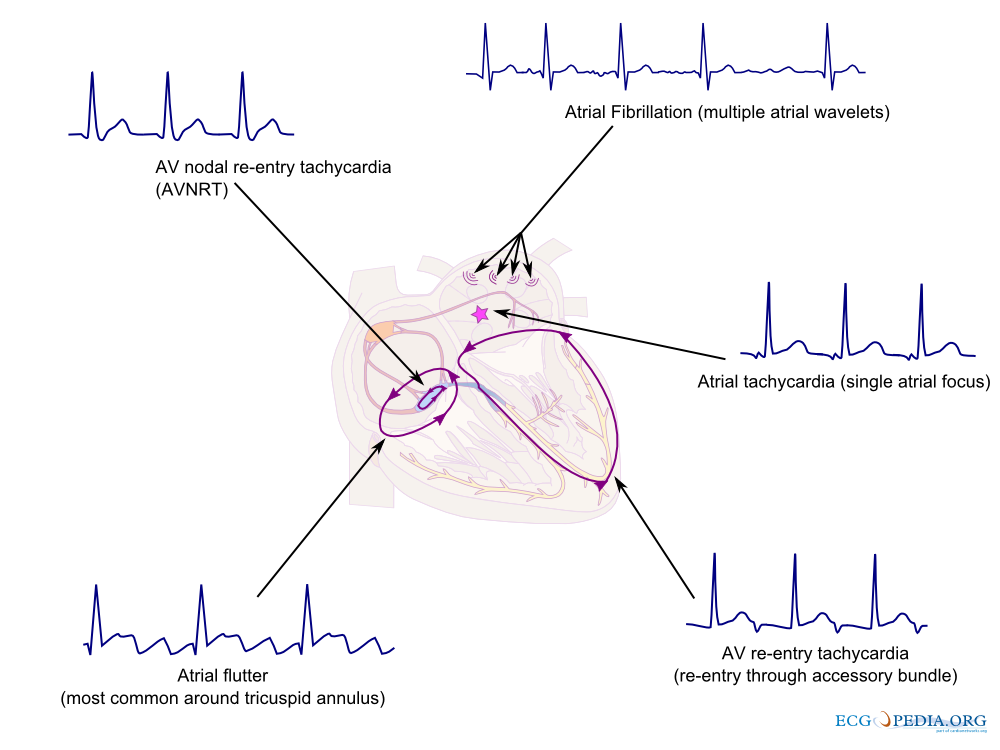

Types of SVTs

Supraventricular tachycardia is properly used as a general term that encompasses a number of different arrhythmias of the heart, each with a different mechanism of impulse maintenance. These are listed below.

Unfortunately, the term SVT is often loosely applied to just the subgroup of AV nodal re-entrant tachycardias.

SVTs from a SINOATRIAL source:

- Sinus tachycardia

- Inappropriate sinus tachycardia

- Sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia (SANRT)

SVTs from an ATRIAL source:

- (Unifocal) Atrial tachycardia (AT)

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT)

- Atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response

- Atrial flutter with a rapid ventricular response

SVTs from an ATRIOVENTRICULAR source:

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT)

- AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT)

- Junctional ectopic tachycardia

Diagnosis

Most supraventricular tachycardias have a narrow QRS complex on EKG, but it is important to realise that supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction (SVTAC) can produce a wide-complex tachycardia that may mimic ventricular tachycardia (VT). In the clinical setting, it is important to determine whether a wide-complex tachycardia is an SVT or a ventricular tachycardia, since they are treated differently. Ventricular tachycardia has to be treated appropriately, since it can quickly degenerate to ventricular fibrillation and death. A number of different algorithms have been devised to determine whether a wide complex tachycardia is supraventricular or ventricular in origin.[1]

In general, a history of structural heart disease dramatically increases the likelihood that the tachycardia is ventricular in origin.

The individual subtypes of SVT can be distinguished from each other by certain physiological and electrical characteristics, many of which present in the patient's EKG.

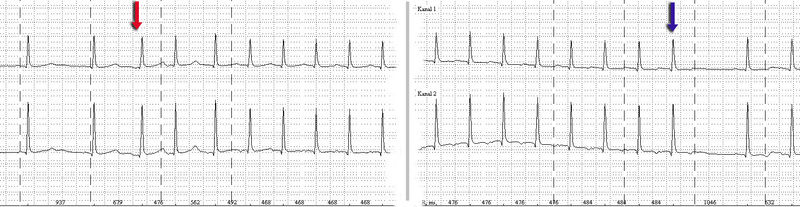

-

Holter monitor-Imaging with start (red arrow) and end (blue arrow) of a SV-tachycardia with a pulse frequency of about 128/min.

- Sinus tachycardia is considered "appropriate" when a reasonable stimulus, such as the catecholamine surge associated with fright, stress, or physical activity, provokes the tachycardia. It is distinguished by a presentation identical to a normal sinus rhythm except for its fast rate (>100 beats per minute in adults).

- Sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia (SANRT) is caused by a reentry circuit localised to the SA node, resulting in a normal-morphology p-wave that falls before a regular, narrow QRS complex. It is therefore impossible to distinguish on the EKG from ordinary sinus tachycardia. It may however be distinguished by its prompt response to Vagal manouvres.

- (Unifocal) Atrial tachycardia is tachycardia resultant from one ectopic foci within the atria, distinguished by a consistent p-wave of abnormal morphology that fall before a narrow, regular QRS complex.

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is tachycardia resultant from at least three ectopic foci within the atria, distinguished by p-waves of at least three different morphologies that all fall before regular, narrow QRS complexes.

- Atrial fibrillation is not, in itself, a tachycardia, but when it is associated with a rapid ventricular response greater than 100 beats per minute, it becomes a tachycardia. A-fib is characteristically an "irregularly irregular rhythm" both in its atrial and ventricular depolarizations. It is distinguished by fibrillatory p-waves that, at some point in their chaos, stimulate a response from the ventricles in the form of irregular, narrow QRS complexes.

- Atrial flutter, is caused by a re-entry rhythm in the atria, with a regular rate of about 300 beats per minute. On the EKG, this appears as a line of "sawtooth" p-waves. The AV node will not usually conduct such a fast rate, and so the P:QRS usually involves a 2:1 or 4:1 block pattern, (though rarely 3:1, and most rarely and sometimes fatally 1:1). Because the ratio of P to QRS is usually consistent, A-flutter is often regular in comparison to its irregular counterpart, A-fib. Atrial Flutter is also not necessarily a tachycardia unless the AV node permits a ventricular response greater than 100 beats per minute.

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) is also sometimes referred to as a junctional reciprocating tachycardia. It involves a reentry circuit forming just next to or within the AV node itself. The circuit most often involves two tiny pathways one faster than the other, within the AV node. Because the AV node is immediately between the atria and the ventricle, the re-entry circuit often stimulates both, meaning that a retrogradely conducted p-wave is buried within or occurs just after the regular, narrow QRS complexes.

- Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) also results from a reentry circuit, although one physically much larger than AVNRT. One portion of the circuit is usually the AV node, and the other, an abnormal accessory pathway from the atria to the ventricle. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a relatively common abnormality with an accessory pathway, the Bundle of Kent crossing the A-V valvular ring.

- In orthodromic AVRT, atrial impulses are conducted down through the AV node and retrogradely re-enter the atrium via the accessory pathway. A distinguishing characteristic of orthodromic AVRT can therefore be a p-wave that follows each of its regular, narrow QRS complexes, due to retrograde conduction.

- In antidromic AVRT, atrial impulses are conducted down through the accessory pathway and re-enter the atrium retrogradely via the AV node. Because the accessory pathway initiates conduction in the ventricles ouside of the bundle of His, the QRS complex in antidromic AVRT is often wider than usual, with a delta wave.

- Finally, Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia or JET is a rare tachycardia caused by increased automaticity of the AV node itself initiating frequent heart beats. On the EKG, junctional tachycardia often presents with abnormal morphology p-waves that may fall anywhere in relation to a regular, narrow QRS complex.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute Treatment

In general, SVT is not life threatening, but episodes should be treated or prevented. While some treatment modalities can be applied to all SVTs with impunity, there are specific therapies available to cure some of the different sub-types. Cure requires intimate knowledge of how and where the arrhythmia is initiated and propagated.

The SVTs can be separated into two groups, based on whether they involve the AV node for impulse maintenance or not. Those that involve the AV node can be terminated by slowing conduction through the AV node. Those that do not involve the AV node will not usually be stopped by AV nodal blocking manoevres. These manoevres are still useful however, as transient AV block will often unmask the underlying rhythm abnormality.

AV nodal blocking can be achieved in at least three different ways:

Physical maneuvers

A number of physical maneuvers cause increased AV nodal block, principally through activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, conducted to the heart by the Vagus nerve. These manipulations are therefore collectively referred to as vagal maneuver.

The best recognised of these is the Valsalva maneuver, which increases intra-thoracic pressure and affects baro-receptors (pressure sensors) within the arch of the aorta. This can be achieved by asking the patient to hold their breath and "bear down" as if straining to pass a bowel motion, or less embarrassingly, by getting them to hold their nose and blow out against it. Plunging the face into, or just drinking a glass of ice cold water is also often effective. Firmly pressing the bulb at the top of one of the carotid arteries in the neck (carotis sinus massage, stimulating carotid baro-receptors) is also effective, but not recommended for those without adequate medical training.

Drug Treatment

Another modality involves treatment with medications. Prehospital care providers and hospital clinicians might administer Adenosine, an ultra short acting AV nodal blocking agent. If this works, followup therapy with Diltiazem, Verapamil or Metoprolol may be indicated. SVT that does NOT involve the AV node may respond to other anti-arrhythmic drugs such as Sotalol or Amiodarone.

In pregnancy, Metoprolol is the treatment of choice as recommended by the American Heart Association.

Electrical Cardioversion

If physical maneuvers or drugs do not work, or if the patient is extremely unstable, a DC shock delivered to the chest (synchronized cardioversion) may also be used, and is almost always effective.

Prevention & Cure

Once the acute episode has been terminated, ongoing treatment may be indicated to prevent a recurrence of the arrhythmia. Patients who have a single isolated episode, or infrequent and minimally symptomatic episodes usually do not warrant any treatment except observation.

Patients who have more frequent or disabling symptoms from their episodes generally warrant some form of preventative therapy. A variety of drugs including simple AV nodal blocking agents like beta-blockers and verapamil, as well as anti-arrhythmics may be used, usually with good effect, although the risks of these therapies need to be weighed against the potential benefits.

For supraventricular tachycardia caused by a re-entrant pathway, another form of treatment is radiofrequency ablation. This is a low risk procedure that uses a catheter inside the heart to deliver radiofrequency energy to locate and destroy the abnormal electrical pathways. Ablation has been shown to be highly effective: up to 99% effective in eliminating AVNRT, and similar results in typical Atrial flutter.

See also

- Tachycardia

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT)

- AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT)

- Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

- Ashman phenomenon

References

External links

- Supraventricular Tachycardia information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center