Sandbox john2

Natural

Ebola infection commonly occurs from direct contact with the virus through mucosal surfaces, cuts on the skin, or parenterally. The risk of infection is increased when there is contact with patients or cadavers infected by the virus. When the virus is in the body, it commonly takes 2 - 21 days for symptoms to develop. Often patients who have a fatal outcome, have earlier symptoms, dying between the 6th and 16th day of disease from multiorgan failure and shock.

Although different species of Ebola virus have different clinical manifestations, a common progression of symptoms includes 2 phases:[1][2][3]

- Phase 1 - characterized by general symptoms, such as: fever, chills, asthenia and headache.

After phase 1, there is a pseudoremission phase, in which patients' clinical status improve for 24 - 48 hours.

- Phase 2 - characterized by severe symptoms, such as neuropsychiatric changes and hemorrhagic manifestations.

Patients who only manifest phase 1 symptoms have better survival rate, than patients who evolve into phase 2 symptoms.

- patients who die, generally die in the first two weeks.

- The ebola virus disease can course with or without hemorrhage.

- Hemorrhage signs are usually associated with abdominal pain and diarrhea.

- Anorexia, nausea, sore throat and postration are symptoms usually associated with non-hemorrhagic ebola virus disease.

- * Without treatment, the patient may develop symptoms of shock, which may eventually lead to death.[3]

- The convalescence period is associated with asthenia and arthralgia.[4]

- If the fever continues after 3 days of recommended treatment, and if the patient shows evidence of bleeding or shock, consider a VHF

- Review the patient’s history for any contact with someone who was ill, with fever and bleeding or who died from an unexplained illness with these symptoms.

Begin VHF Isolation Precautions.[5]

- Fewer than 50 percent of patients will not develop any hemorrhage.

- A history of contact with another infected individual should be elicited particularly in the setting of an outbreak.

- In non-fatal cases, patients have fever for several days and improve typically around day 6–11, about the time that the humoral antibody response is noted.1,40 Patients with non-fatal or asymptomatic disease mount specific IgM and IgG responses that seem to be associated with a temporary early and strong inflammatory response, including interleukin β, interleukin 6, and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα).

LABORATORY Laboratory variables are less characteristic but the following findings are often associated with Ebola haemorrhagic fever: early leucopenia (as low as 1000 cells per μL) with lymphopenia and subsequent neutrophilia, left shift with atypical lymphocytes, thrombocytopenia (50000–100000 cells per μL), highly raised serum aminotransferase concentrations (aspartate amino- transferase typically exceeding alanine aminotransferase), hyperproteinaemia, and proteinuria. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times are extended and fibrin split products are detectable, indicating diffuse intravascular coagulopathy. In a later stage, secondary bacterial infection might lead to raised counts of white blood cells.1,37–39

In Progress

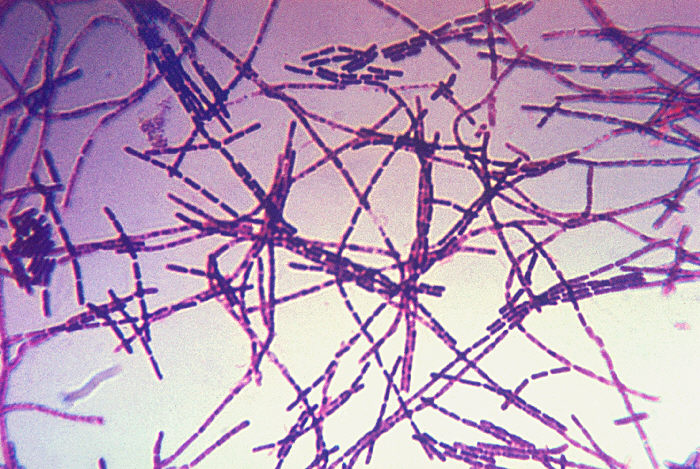

Bacillus anthracis is a rod-shaped Gram-positive bacterium, about 1 by 9 micrometers in size. It was shown to cause disease by Robert Koch in 1877. [2] The bacterium normally rests in endospore form in the soil, and can survive for decades in this state. Once ingested by a ruminant or placed in an open cut, the bacterium begins multiplying inside the animal or human and in a few days to a month kills it. Veterinarians can often tell a possible anthrax induced death by its sudden occurrence and by the blood and bloody fluids that oozed from the body orifices. Most anthrax bacteria inside the body are destroyed by anaerobic bacteria that can grow without oxygen. The greater danger lies in the bodily fluids and blood that spills from the body and spill into the soil where the anthrax bacteria turn into a dormant protective spore form. Once formed the spores are very hard to eradicate.

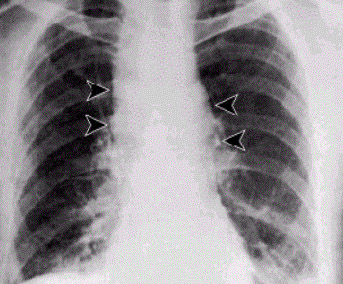

The infection of ruminants (and occasionally humans) normally proceeds as follows: once the spores are inhaled they are transported through the air passages into the tiny air sacs (alveoli) in the lungs. The spores are then picked up by scavenger cells (macrophages) in the lungs and are transported through small vessels (lymphatics) to the glands (lymph nodes) in the central chest cavity (mediastinum). Damage caused by the anthrax spores and bacilli to the central chest cavity lungs can cause chest pain and difficulty breathing. Once in the lymph glands, the spores germinate into active bacillus, that multiplies, and eventually bursts the macrophage cell, releasing many more bacilli into the bloodstream which are transferred to the entire body. Once in the blood stream these bacilli release a tripartite toxin (composed of lethal factor, edema factor and protective antigen) which is known to be the primary agents of tissue destruction, bleeding, and death. If antibiotics are given too late, even if the antibiotics eradicate the bacteria, some people still will die because the toxins produced by the bacilli still remain in their system at lethal dose levels.

In order to enter the cells, the toxins use another protein produced by B. anthracis, protective antigen. Edema factor inactivates neutrophils (a type of phagocytic cell) so that they cannot phagocytose bacteria. Historically, it was believed that lethal factor caused macrophages to make TNF-alpha and interleukin 1, beta (IL1B), both normal components of the immune system used to induce an inflammatory reaction, ultimately leading to septic shock and death. However, recent evidence indicates that anthrax also targets endothelial cells (cells that lines serous cavities, lymph vessels, and blood vessels), causing vascular leakage (similar to hemorrhagic bleeding), and ultimately hypovolemic shock (low blood volume), and not only septic shock. In other words the patient bleeds to death internally.

The virulence of a strain of anthrax is dependent on multiple factors, primarily the poly-D-glutamic acid capsule that protects the bacterium from phagocytosis by host neutrophils and its toxins, edema toxin and lethal toxin.

Pathophysiology

Exposure

Occupational exposure to infected animals or their products (such as skin wool and meat) is the usual pathway of exposure for humans. Workers who are exposed to dead animals and animal products are at the highest risk, especially in countries where anthrax is more common. Anthrax in livestock grazing on open range where they mix with wild animals still occasionally occurs in the United States and elsewhere. Many workers who deal with wool and animal hides are routinely exposed to low levels of anthrax spores but most exposures are not sufficient to develop anthrax infections. Presumably, the body’s natural defenses can destroy low levels of exposure. These people usually contract cutaneous anthrax if they catch anything. Historically, the most dangerous form of inhalation anthrax was called Woolsorters' disease because it was an occupational hazard for people who sorted wool. Fortunately this is now a very rare form of infection because of the much reduced incidence of anthrax disease in animals. The last fatal case of natural inhalation anthrax in the United States occurred in California in 1976, when a home weaver died after working with infected wool imported from Pakistan. The autopsy was done at UCLA hospital. To minimize the chance of spreading the disease, the deceased was transported to UCLA in a sealed plastic body bag within a sealed metal container. The details of this case have been described in a medical journal Human Pathology (Volume 9, pages 594-597, September, 1978).

In July 2006 an artist who worked with untreated animal skins became the first person in more than 30 years to die in the United Kingdom from anthrax.[6]

Mode of infection

Anthrax can enter the human body through the intestines (ingestion), lungs (inhalation), or skin (cutaneous) and causes distinct clinical symptoms based on its site of entry. An infected human will generally be quarantined. However, anthrax does not usually spread from an infected human to a noninfected human. But if the disease is fatal the person’s body and its mass of anthrax bacilli becomes a potential source of infection to others and special precautions should be used to prevent more contamination. Unfortunately inhalation anthrax, if left untreated until obvious symptoms occur, will usually result in death if treatment is started too late.

Anthrax is usually contracted by handling infected animals or their wool, germ warfare/terrorism or laboratory accidents.

1) Pulmonary (pneumonic, respiratory, or inhalation) anthrax Respiratory infection initially presents with cold or flu-like symptoms for several days, followed by severe (and often fatal) respiratory collapse. If not treated promptly soon after exposure, before symptoms appear, inhalational anthrax is highly fatal, with near 100% mortality.[7] A lethal dose of anthrax is reported to result from inhalation of about 10,000–20,000 spores. [8] Like all diseases there is probably a wide variation to susceptibility with evidence that some people may die from much lower exposures; there is little documented evidence to verify the exact or average number of spores need for infection. Inhalation anthrax is also known as Woolsorters' disease or as Ragpickers' disease since these people often caught it. Other practices associated with exposure include the slicing up of animal horns for the manufacture of buttons, the handling of hair bristles used for the manufacturing of brushes, and the handling of animal skins. Whether these animal skins came from animals that died of the disease or from animals that had simply laid on ground that had spores on it is unknown. Anthrax is a very hard disease to eliminate since Anthrax spores are devilishly hard to kill and have been known to have reinfected animals over 70 years after burial sites of anthrax infected animals were disturbed. [9]

2) Gastrointestinal (gastroenteric) anthrax Gastrointestinal infection is most often caused by eating anthrax infected meat and is characterized by serious gastrointestinal difficulty, vomiting of blood, severe diarrhea, acute inflammation of the intestinal tract, and loss of appetite. Gastrointestinal infections can be treated but usually result in fatality rates of 25% to 60%, depending upon how soon treatment commences. [10]

3) Cutaneous (skin) anthrax

Cutaneous (on the skin) anthrax infection shows up as a boil-like skin lesion that eventually forms an ulcer with a black center (i.e., eschar). The black eschar often shows up as a large, painless necrotic ulcers (beginning as an irritating and itchy skin lesion or blister that is dark and usually concentrated as a black dot, somewhat resembling bread mold) at the site of infection. Cutaneous infections generally form within the site of spore penetration within 2 to 5 days after exposure. Unlike bruises or most other lesions, cutaneous anthrax infections normally do not cause pain. Cutaneous infection is the least fatal form of anthrax infection if treated. But without treatment, approximately 20% of all cutaneous skin infection cases may progress to toxemia and death. [11] Treated cutaneous anthrax is rarely fatal.[7]

Demographics

Smallpox killed an estimated 60 million europeans, including five reigning European monarchs, in the 18th century alone. Up to 30% of those infected, including 80% of the children under 5 years of age, died from the disease, and one third of the survivors became blind.[12][13]

Smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300–500 million deaths in the 20th century. As recently as 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year.[14] After first contacts with Europeans and Africans, some believe that the death of 90 to 95 percent of the native population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases.[15] It is suspected that smallpox was the chief culprit and responsible for killing nearly all of the native inhabitants of the Americas. For more than two hundred years, this disease affected all new world populations, mostly without intentional European transmission (Excluding the British Settlements), from contact in the early 1500s to until possibly as early as the French and Indian Wars (1754-1767).[16]

The eradication of smallpox required a global effort. Every country was susceptible to the devastating disease. Eradicating this infection would take many years a significant sum of money, but with a worldwide commitment, it would be possible. Success was achieved in the 1970s and smallpox was officially eradicated.

The Americas

| Documented Smallpox Epidemics in the New World[17] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Location | Description |

| 1520-1527 | Mexico, Central America, South America | Smallpox kills millions of native inhabitants of Mexico. Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Panfilo de Narvaez on April 23, 1520[18] and was credited with the victory of Cortes over the Aztec empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521. Kills the Inca ruler, Huayna Capac, and 200,000 others and destroys the Incan Empire. |

| 1617-1619 | North America northern east coast | Killed 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Indians |

| 1674 | Cherokee Tribe | Death count unknown. Population in 1674 about 50,000. After 1729, 1738, and 1753 smallpox epidemics their population was only 25,000 when they were forced to Oklahoma on the Trail Of Tears |

| 1692 | Boston, MA | |

| 1702-1703 | St. Lawrence Valley, NY | |

| 1721 | Boston, MA | |

| 1736 | Pennsylvania | |

| 1738 | South Carolina | |

| 1754-1767 | North East U.S. and South East Canada | "Smallpox was probably first used as a biological weapon during the French and Indian Wars of 1754-1767 when British forces in North America distributed blankets that had been used by smallpox patients among them to Native Americans collaborating with the French."[16] |

| 1770s | West Coast of North America | Kills out 30% of the West Coast Native Americans |

| 1781-1783 | Great Lakes | |

| 1830s | Alaska | Reduced Dena'ina Athabaskan population in Cook Inlet region of southcentral Alaska by half.[19] Smallpox also devastated Yup'ik Eskimo populations in western Alaska. |

| 1860-1861 | Pennsylvania | |

| 1865-1873 | Philadelphia, PA, New York, Boston, MA and New Orleans, LA | Same period of time, in Washington DC, Baltimore, MD, Memphis, TN Cholera and a series of recurring epidemics of Typhus, Scarlet Fever and Yellow Fever |

| 1877 | Los Angeles, CA | |

After first contacts with Europeans and Africans, some believe that the death of 90 to 95 percent of the native population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases.[20] It is suspected that smallpox was the chief culprit and responsible for killing nearly all of the native inhabitants of the Americas. For more than two hundred years, this disease affected all new world populations, mostly without intentional European transmission (Excluding the British Settlements), from contact in the early 1500s to until possibly as early as the French and Indian Wars (1754-1767).[16]

In 1519 Hernán Cortés landed on the shores of what is now Mexico and was then the Aztec empire. In 1520 another group of Spanish came from Cuba and landed in Mexico. Among them was an African slave who had smallpox. When Cortés heard about the other group, he went and defeated them. In this contact, one of Cortés's men contracted the disease. When Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan, he brought the disease with him.

Soon, the Aztecs rose up in rebellion against Cortés. Outnumbered, the Spanish were forced to flee. In the fighting, the Spanish soldier carrying smallpox died. After the battle, the Aztecs contracted the virus from the invaders' bodies. Cortes would not return to the capital until August 1521. In the meantime smallpox devastated the Aztec population. It killed most of the Aztec army, the emperor, and 25% of the overall population. A Spanish priest left this description: "As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease…they died in heaps, like bedbugs. In many places it happened that everyone in a house died and, as it was impossible to bury the great number of dead, they pulled down the houses over them so that their homes become their tombs." On Cortés's return, he found the Aztec army’s chain of command in ruins. The soldiers who lived were still weak from the disease. Cortés then easily defeated the Aztecs and entered Tenochtitlán, where he found that smallpox had killed more Aztecs than had the cannons. The Spaniards said that they could not walk through the streets without stepping on the bodies of smallpox victims.

The effects of smallpox on Tahuantinsuyu (or the Inca empire) were even more devastating. Beginning in Colombia, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived in the empire. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Within months, the disease had killed the Sapa Inca Huayna Capac, his successor, and most of the other leaders. Two of his surviving sons warred for power and, after a bloody and costly war, Atahualpa become the new Sapa Inca. As Atahualpa was returning to the capital Cuzco, Francisco Pizarro arrived and through a series of deceits captured the young leader and his best general. Within a few years smallpox claimed between 60% and 90% of the Inca population[21], with other waves of European disease weakening them further. However, some historians think a serious native disease called Bartonellosis may have been responsible for some outbreaks of illness. The effects of smallpox were dipicted in the ceramics of the Moche people of ancient Peru. [22]

Even after the two mighty empires of the Americas were defeated by the virus, smallpox continued its march of death. In 1633 in Plymouth, Massachusetts, the Native Americans were struck by the virus. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population groups of Native Americans. It reached Lake Ontario in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois by 1679, killing millions. The worst sequence of smallpox attacks took place in Boston, Massachusetts. From 1636 to 1698, Boston endured six epidemics. In 1721, the most severe epidemic occurred. The entire population fled the city, bringing the virus to the rest of the Thirteen Colonies. In the late 1770s, during the American Revolutionary War, smallpox returned once more and killed an estimated 125,000 people.[23] Peter Kalm in his “Travels in North America”, described how in that period, the dying Indian villages became overrun with wolves feasting on the corpses and weakened survivors.[24]

Eurasia

It is important to note that, while historical epidemics and pandemics are believed by some historians to have been early outbreaks of smallpox, contemporary records are not detailed enough to make a definite diagnosis at this distance.[25]

The Plague of Athens devastated the city of Athens in 430 BC, killing around a third of the population, according to Thucydides. Historians have long considered this an example of bubonic plague, but more recent examination of the reported symptoms led some scholars to believe the cause may have been measles, smallpox, typhus, or a viral hemorrhagic fever (like Ebola).

The Antonine Plague that swept through the Roman Empire and Italy in 165–180 is also thought to be either smallpox or measles.[26] [25] A second major outbreak of disease in the Empire, known as the Plague of Cyprian (251–266), was also either smallpox or measles.

The next major epidemic believed to be smallpox occurred in India]. The exact date is unknown. Around A.D. 400, an Indian medical book recorded a disease marked by pustules, saying "the pustules are red, yellow, and white and they are accompanied by burning pain … the skin seems studded with grains of rice." The Indian epidemic was thought to be punishment from a god, and the survivors created a goddess, Sitala, as the anthropomorphic personification of the disease.[27][28][29] Smallpox was thus regarded as possession by Sitala. In Hinduism the goddess Sitala both causes and cures high fever, rashes, hot flashes and pustules. All of these are symptoms of smallpox.

Smallpox did not definitively enter Western Europe until about 581 when Bishop Gregory of Tours provided an eyewitness account that describes the characteristic findings of smallpox.[25] Most of the details about the epidemic that followed are lost, probably due to the scarcity of surviving written records of early medieval society.

Pathophysionology

Random notes

References

- ↑ Ndambi R, Akamituna P, Bonnet MJ, Tukadila AM, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Colebunders R (1999). "Epidemiologic and clinical aspects of the Ebola virus epidemic in Mosango, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995". J Infect Dis. 179 Suppl 1: S8–10. doi:10.1086/514297. PMID 9988156.

- ↑ Bwaka MA, Bonnet MJ, Calain P, Colebunders R, De Roo A, Guimard Y; et al. (1999). "Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo: clinical observations in 103 patients". J Infect Dis. 179 Suppl 1: S1–7. doi:10.1086/514308. PMID 9988155.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Feldmann H, Geisbert TW (2011). "Ebola haemorrhagic fever". Lancet. 377 (9768): 849–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. PMC 3406178. PMID 21084112.

- ↑ Sureau PH (1989). "Firsthand clinical observations of hemorrhagic manifestations in Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Zaire". Rev Infect Dis. 11 Suppl 4: S790–3. PMID 2749110.

- ↑ "Infection Control for Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting" (PDF). line feed character in

|title=at position 75 (help) - ↑ Artist dies from anthrax caught from animal skins Independent News and Media Limited, 17 August 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bravata DM, Holty JE, Liu H, McDonald KM, Olshen RA, Owens DK (2006), Systematic review: a century of inhalation anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005, Annals of Internal Medicine; 144(4): 270–80.

- ↑ "www.medicinenet.com". Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- ↑ "Anthrax" by Jeanne Guillemin, University of California Press, 2001,ISBN 0-520-22917-7, pg. 3

- ↑ "Anthrax Q & A: Signs and Symptoms". Emergency Preparedness and Response. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ "Anthrax Q & A: Signs and Symptoms". Emergency Preparedness and Response. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ Barquet N, Domingo P (1997). "Smallpox: the triumph over the most terrible of the ministers of death". Ann. Intern. Med. 127 (8 Pt 1): 635–42. PMID 9341063.

- ↑ Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination

- ↑ "Smallpox". WHO Factsheet. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ↑ The Story Of... Smallpox

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Henderson DA, Inglesby TV, Bartlett JG; et al. (1999). "Smallpox as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense" (PDF). JAMA. 281 (22): 2127–37. PMID 10367824.

- ↑ [1] Worldwide Epidemics 1999 Genealogy Inc

- ↑ The Demon in the Freezer

- ↑ Boraas AS (1991). Peter Kalifornsky: A Biography. In: A Dena’ina Legacy — K’tl’egh’i Sukdu: The Collected Writings of Peter Kalifornsky (Kari J, Boraas AS, eds). Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. p. 475.

- ↑ The Story Of... Smallpox

- ↑ Silent Killers of the New World

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ Fenn EA (2001). Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82 (1st ed. ed.). Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-7820-1.

- ↑ "Groundhog day at the wolf wars". Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Hopkins DR (2002). The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in history. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-35168-8. Originally published as Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History (1983), ISBN 0-226-35177-7

- ↑ Annals of Internal Medicine

- ↑ Nicholas R (1981). "The goddess Sitala and epidemic smallpox in Bengal". J Asian Stud. 41 (1): 21–45. PMID 11614704.

- ↑ "Sitala and Smallpox". The thermal qualities of substance: Hot and Cold in South Asia. Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- ↑ http://reli350.vassar.edu/kissane/sitala.html Vassar: Points out that variolation was regarded as a means of invoking the goddess whereas vaccination was opposition to her. Gives duration of belief as until 50 years ago.