Sandbox john2: Difference between revisions

Joao Silva (talk | contribs) |

Joao Silva (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Smallpox is not notably infectious in the [[prodrome|prodromal]] period—viral shedding is usually delayed until the appearance of the rash. | Smallpox is not notably infectious in the [[prodrome|prodromal]] period—viral shedding is usually delayed until the appearance of the rash. | ||

The incubation period between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease is around 12 days. | The incubation period between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease is around 12 days. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 19: | ||

If the patient survives the course of the disease, the pustules deflate in time (the duration is variable), and start to dry up, usually beginning on day 28. Eventually the pustules completely dry and start to flake off. Once all of the pustules flake off, the patient is considered cured, and is no longer contagious. | If the patient survives the course of the disease, the pustules deflate in time (the duration is variable), and start to dry up, usually beginning on day 28. Eventually the pustules completely dry and start to flake off. Once all of the pustules flake off, the patient is considered cured, and is no longer contagious. | ||

===Hemorrhagic Smallpox=== | ===Hemorrhagic Smallpox=== | ||

Revision as of 20:47, 9 July 2014

In Progress

Pathophysionology

Pathophysiology

Infection

Smallpox is not notably infectious in the prodromal period—viral shedding is usually delayed until the appearance of the rash.

The incubation period between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease is around 12 days.

In the initial growth phase the virus seems to move from cell to cell, but around the 12th day, lysis of many infected cells occurs and the virus is found in the bloodstream in large numbers.

Smallpox virus preferentially attacks skin cells, and by days 12–15, smallpox infection becomes obvious. The attack on skin cells causes the characteristic pimples associated with the disease. The pimples tend to erupt first in the mouth, then on the arms and the hands, and later on the rest of the body. At this point the pimples, called macules, are usually still fairly small. This is the stage at which the victim is most contagious.

By days 15–16 the condition worsens, and at this point the disease can take two very different courses, depending on whether it is ordinary or hemorrhagic smallpox.

The most common type is classic ordinary smallpox, in which the pimples grow into vesicles and then fill up with pus, turning them into pustules. Ordinary smallpox generally takes one of two basic courses. In discrete ordinary smallpox, the pustules stand out on the skin separately. There is a greater chance of surviving this form. In confluent ordinary smallpox, the blisters merge together into sheets which begin to detach the outer layers of skin from the underlying flesh. This form is usually fatal.

If the patient survives the course of the disease, the pustules deflate in time (the duration is variable), and start to dry up, usually beginning on day 28. Eventually the pustules completely dry and start to flake off. Once all of the pustules flake off, the patient is considered cured, and is no longer contagious.

Hemorrhagic Smallpox

In the other form of Variola major smallpox, known as hemorrhagic smallpox, a mortality of 96 percent has been reported. An entirely different set of symptoms starts to develop. The skin does not blister, but remains smooth. Instead, bleeding occurs under the skin, making the skin look charred and black (this is known as black pox). The eyes also hemorrhage, making the whites of the eyes turn deep red (and, if the victim lives long enough, black). At the same time, bleeding begins in the organs. Death may occur from bleeding (fatal loss of blood or by other causes such as brain hemorrhage), or from loss of fluid. The entry of other infectious organisms, since the skin and intestine are no longer a barrier, can also lead to multi-organ failure. This form of smallpox occurs in anywhere from 3–25% of fatal cases (depending on the virulence of the smallpox strain).

The historical modes of death are similar to those in burns, with catastrophic losses of fluid, protein and electrolytes beyond the capacity of the body to replace or assimilate, and fulminating sepsis, both due to the removal of the barrier between the internal milieu and outside world. Supportive treatments have improved since the last large smallpox epidemics, but it would be grossly optimistic to imagine that, even with a small number of patients, the most intensive modern treatment would ensure survival, even where the damage is predominantly only in the skin. A reduction in the severity of the disease by raising immunity is likely to make a large difference in numbers reaching the threshold of death, and supportive treatment a small one in elevating that threshold.

Random notes

Acute Pharmacotherapy

Until the development of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine in the 1940s, there was no effective cure for leprosy. However, dapsone is only weakly bactericidal against M. leprae and it was considered necessary for patients to take the drug indefinitely. Moreover, when dapsone was used alone, the M. leprae population quickly evolved antibiotic resistance; by the 1960s, the world's only known anti-leprosy drug became virtually useless.

The search for more effective anti-leprosy drugs to dapsone led to the use of clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s.[1] Later, Shantaram Yawalkar and colleagues formulated a combined therapy using rifampicin and dapsone, intended to mitigate bacterial resistance.[2] Multidrug therapy (MDT) and combining all three drugs was first recommended by a WHO Expert Committee in 1981. These three anti-leprosy drugs are still used in the standard MDT regimens. None of them are used alone because of the risk of developing resistance.

Because this treatment is quite expensive, it was not quickly adopted in most endemic countries. In 1985 leprosy was still considered a public health problem in 122 countries. The 44th World Health Assembly (WHA), held in Geneva in 1991 passed a resolution to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem by the year 2000 — defined as reducing the global prevalence of the disease to less than 1 case per 100,000. At the Assembly, the World Health Organization (WHO) was given the mandate to develop an elimination strategy by its member states, based on increasing the geographical coverage of MDT and patients’ accessibility to the treatment.

The WHO Study Group's report on the Chemotherapy of Leprosy in 1993 recommended two types of standard MDT regimen be adapted.[3] The first was a 24-month treatment for multibacillary (MB or lepromatous) cases using rifampicin, clofazimine, and dapsone. The second was a six-month treatment for paucibacillary (PB or tuberculoid) cases, using rifampicin and dapsone. At the First International Conference on the Elimination of Leprosy as a Public Health Problem, held in Hanoi the next year, the global strategy was endorsed and funds provided to WHO for the procurement and supply of MDT to all endemic countries.

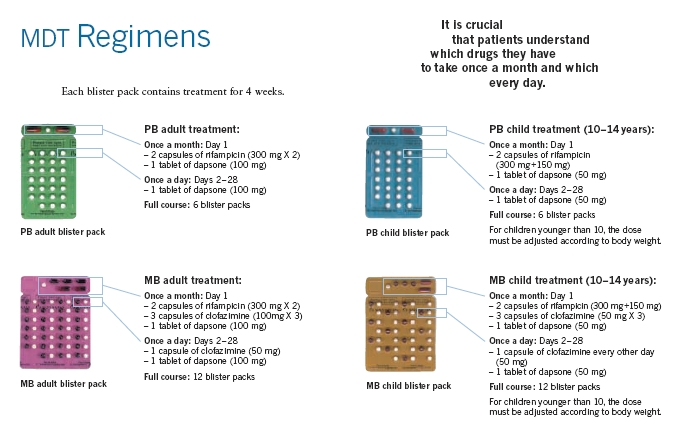

Since 1995, WHO has supplied all endemic countries with free MDT in blister packs, supplied through Ministries of Health. This free provision was extended in 2000, and again in 2005, and will run until at least the end of 2010. At the national level, non-government organisations (NGOs) affiliated to the national programme will continue to be provided with an appropriate free supply of this MDT by the government.

MDT remains highly effective and patients are no longer infectious after the first monthly dose. It is safe and easy to use under field conditions due to its presentation in calendar blister packs. Relapse rates remain low, and there is no known resistance to the combined drugs. The Seventh WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, [4] reporting in 1997, concluded that the MB duration of treatment—then standing at 24 months—could safely be shortened to 12 months "without significantly compromising its efficacy."

Persistent obstacles to the elimination of the disease include improving detection, educating patients and the population about its cause, and fighting social taboos about a disease for which patients have historically been considered "unclean" or "cursed by God" as outcasts. Where taboos are strong, patients may be forced to hide their condition (and avoid seeking treatment) to avoid discrimination. The lack of awareness about Hansen's disease can lead people to falsely believe that the disease is highly contagious and incurable.

References

- ↑ Rees RJ, Pearson JM, Waters MF (1970). "Experimental and clinical studies on rifampicin in treatment of leprosy". Br Med J. 688 (1): 89–92. PMID 4903972.

- ↑ Yawalkar SJ, McDougall AC, Languillon J, Ghosh S, Hajra SK, Opromolla DV, Tonello CJ (1982). "Once-monthly rifampicin plus daily dapsone in initial treatment of lepromatous leprosy". Lancet. 8283 (1): 1199–1202. PMID 6122970.

- ↑ "Chemotherapy of Leprosy". WHO Technical Report Series 847. WHO. 1994. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ↑ "Seventh WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy". WHO Technical Report Series 874. WHO. 1998. Retrieved 2007-03-24.