Prostate cancer: Difference between revisions

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

==[[Prostate cancer natural history|Complications & Prognosis]]== | ==[[Prostate cancer natural history|Complications & Prognosis]]== | ||

==Epidemiology== | ==Epidemiology== | ||

Revision as of 18:46, 15 December 2011

For patient information click here

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

|

Prostate cancer Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Prostate cancer On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Prostate cancer |

Steven C. Campbell, M.D., Ph.D. Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [1] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Symptoms

Pathophysiology

Causes

Treatment

Treatment for prostate cancer may involve watchful waiting, surgery, radiation therapy including brachytherapy (prostate brachytherapy) and external beam radiation, High Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU), chemotherapy, cryosurgery, hormonal therapy, or some combination. Which option is best depends on the stage of the disease, the Gleason score, and the PSA level. Other important factors are the man's age, his general health, and his feelings about potential treatments and their possible side effects. Because all treatments can have significant side effects, such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence, treatment discussions often focus on balancing the goals of therapy with the risks of lifestyle alterations.

The selection of treatment options may be a complex decision involving many factors. For example, radical prostatectomy after primary radiation failure is a very technically challenging surgery and may not be an option.[1] This may enter into the treatment decision.

If the cancer has spread beyond the prostate, treatment options significantly change, so most doctors who treat prostate cancer use a variety of nomograms to predict the probability of spread. Treatment by watchful waiting, HIFU, radiation therapy, cryosurgery, and surgery are generally offered to men whose cancer remains within the prostate. Hormonal therapy and chemotherapy are often reserved for disease which has spread beyond the prostate. However, there are exceptions: radiation therapy may be used for some advanced tumors, and hormonal therapy is used for some early stage tumors. Cryotherapy, hormonal therapy, and chemotherapy may also be offered if initial treatment fails and the cancer progresses.

Medical therapy | Surgical options | Metastasis Treatment | Primary prevention | Secondary prevention | Financial costs | Future therapies

Screening

Diagnosis

When a man has symptoms of prostate cancer, or a screening test indicates an increased risk for cancer, more invasive evaluation is offered.

The only test which can fully confirm the diagnosis of prostate cancer is a biopsy, the removal of small pieces of the prostate for microscopic examination. However, prior to a biopsy, several other tools may be used to gather more information about the prostate and the urinary tract. Cystoscopy shows the urinary tract from inside the bladder, using a thin, flexible camera tube inserted down the urethra. Transrectal ultrasonography creates a picture of the prostate using sound waves from a probe in the rectum.

- History and Symptoms | Physical Examination | Staging | Lab Studies | Electrocardiogram | X Ray | MRI | CT | Echocardiography | Other imaging findings | Other diagnostic studies

Risk factors

Complications & Prognosis

Epidemiology

Rates of prostate cancer vary widely across the world. Although the rates vary widely between countries, it is least common in South and East Asia, more common in Europe, and most common in the United States.[2] According to the American Cancer Society, prostate cancer is least common among Asian men and most common among black men, with figures for white men in-between.[3][4] However, these high rates may be affected by increasing rates of detection.[5]

Prostate cancer develops most frequently in men over fifty. This cancer can occur only in men, as the prostate is exclusively of the male reproductive tract. It is the most common type of cancer in men in the United States, where it is responsible for more male deaths than any other cancer, except lung cancer. In the United Kingdom it is also the second most common cause of cancer death after lung cancer, where around 35,000 cases are diagnosed every year and of which around 10,000 die of it. However, many men who develop prostate cancer never have symptoms, undergo no therapy, and eventually die of other causes. That is because malignant neoplasms of the prostate are, in most cases, slow-growing, and because most of those affected are over 60. Hence they often die of causes unrelated to the prostate cancer, such as heart/circulatory disease, pneumonia, other unconnected cancers or old age. Many factors, including genetics and diet, have been implicated in the development of prostate cancer. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial found that finasteride reduces the incidence of prostate cancer rate by 30%. There had been a controversy about this also increasing the risk of more aggressive cancers, but more recent research showed this was not the case.[6][7]

History

Although the prostate was first described by Venetian anatomist Niccolò Massa in 1536, and illustrated by Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius in 1538, prostate cancer was not identified until 1853.[8] Prostate cancer was initially considered a rare disease, probably because of shorter life expectancies and poorer detection methods in the 19th century. The first treatments of prostate cancer were surgeries to relieve urinary obstruction.[9] Removal of the entire gland (radical perineal prostatectomy) was first performed in 1904 by Hugh H. Young at Johns Hopkins Hospital.[10] Surgical removal of the testes (orchiectomy) to treat prostate cancer was first performed in the 1890s, but with limited success. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) replaced radical prostatectomy for symptomatic relief of obstruction in the middle of the 20th century because it could better preserve penile erectile function. Radical retropubic prostatectomy was developed in 1983 by Patrick Walsh.[11] This surgical approach allowed for removal of the prostate and lymph nodes with maintenance of penile function.

In 1941 Charles B. Huggins published studies in which he used estrogen to oppose testosterone production in men with metastatic prostate cancer. This discovery of "chemical castration" won Huggins the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[12] The role of the hormone GnRH in reproduction was determined by Andrzej W. Schally and Roger Guillemin, who both won the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work.

Receptor agonists, such as leuprolide and goserelin, were subsequently developed and used to treat prostate cancer.[13][14]

Radiation therapy for prostate cancer was first developed in the early 20th century and initially consisted of intraprostatic radium implants. External beam radiation became more popular as stronger radiation sources became available in the middle of the 20th century. Brachytherapy with implanted seeds was first described in 1983.[15] Systemic chemotherapy for prostate cancer was first studied in the 1970s. The initial regimen of cyclophosphamide and 5-fluorouracil was quickly joined by multiple regimens using a host of other systemic chemotherapy drugs.[16]

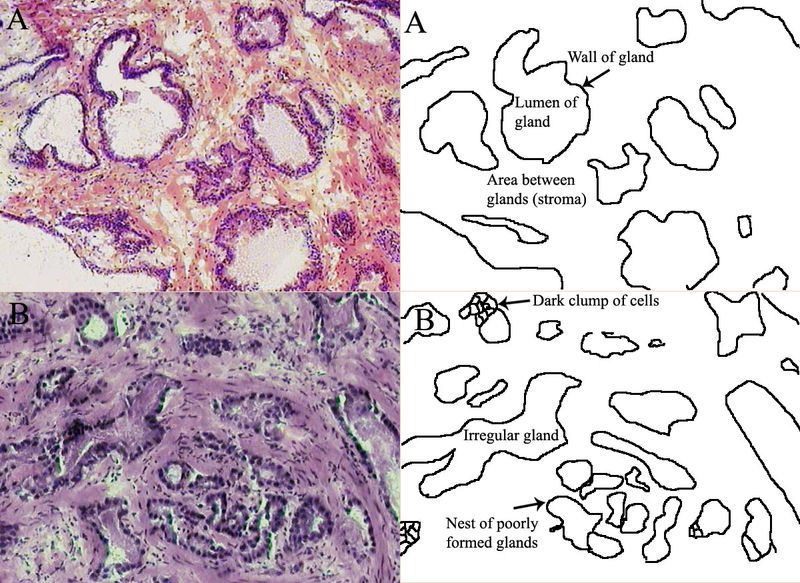

Histopathological Findings in Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma

<youtube v=1SZPLS1dxTo/>

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grading system)

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 1)

<youtube v=F7V0Zl7a2FY/>

Prostate : Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 2)

<youtube v=YSOLiSklIXw/>

Prostate : Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 3)

<youtube v=TG8vR_pE7yA/>

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 4)

<youtube v=R2Cl4HScdGc/>

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 5)

<youtube v=F7V0Zl7a2FY/>

See also

References

- ↑ Mouraviev V, Evans B, Polascik TJ (2006). "Salvage prostate cryoablation after primary interstitial brachytherapy failure: a feasible approach". Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 9 (1): 99–101. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500853. PMID 16314889.

- ↑ "IARC Worldwide Cancer Incidence Statistics—Prostate". JNCI Cancer Spectrum. Oxford University Press. December 19, 2001. Retrieved on 2007-04-05 through the Internet Archive

- ↑ Overview: Prostate Cancer—What Causes Prostate Cancer? American Cancer Society (2006-05-02). Retrieved on 2007-04-05

- ↑ Prostate Cancer FAQs. State University of New York School of Medicine Department of Urology (2006-08-31). Retrieved on 2007-04-05

- ↑ Potosky A, Miller B, Albertsen P, Kramer B (1995). "The role of increasing detection in the rising incidence of prostate cancer". JAMA. 273 (7): 548&ndash, 52. doi:10.1001/jama.273.7.548. PMID 7530782.

- ↑ Gine Kolata (June 15, 2008). "New Take on a Prostate Drug, and a New Debate". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Potosky A, Miller B, Albertsen P, Kramer B (2008). "Finasteride Does Not Increase the Risk of High-Grade Prostate Cancer: A Bias-Adjusted Modeling Approach". Cancer Prevention Research. Published Online First on May 18, 2008 as 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0092: 174. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0092.

- ↑ Adams, J. The case of scirrhous of the prostate gland with corresponding affliction of the lymphatic glands in the lumbar region and in the pelvis. Lancet 1, 393 (1853).

- ↑ Lytton, B. Prostate cancer: a brief history and the discovery of hormonal ablation treatment. J. Urol. 165, 1859–1862

- ↑ Young, H. H. Four cases of radical prostatectomy. Johns Hopkins Bull. 16, 315 (1905).

- ↑ Walsh, P. C., Lepor, H. & Eggleston, J. C. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate 4, 473-485 (1983). PMID 6889192

- ↑ Huggins, C. B. & Hodges, C. V. Studies on prostate cancer: 1. The effects of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res. 1, 203 (1941).

- ↑ Schally, A. V., Kastin, A. J. & Arimura, A. Hypothalamic FSH and LH-regulating hormone. Structure, physiology and clinical studies. Fertil. Steril. 22, 703–721 (1971).

- ↑ Tolis G, Ackman D, Stellos A, Mehta A, Labrie F, Fazekas AT, Comaru-Schally AM, Schally AV. Tumor growth inhibition in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(5):1658–62 PMID 6461861

- ↑ Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. A History of Prostate Cancer Treatment. Nature Reviews Cancer 2, 389–396 (2002). PMID 12044015

- ↑ Scott, W. W. et al. Chemotherapy of advanced prostatic carcinoma with cyclophosphamide or 5-fluorouracil: results of first national randomized study. J. Urol. 114, 909–911 (1975). PMID 1104900

External links

Template:Urogenital neoplasia Template:SIB Template:Link FA Template:Link FA af:Prostaatkanker bn:প্রোস্টেট ক্যান্সার bg:Рак на простатата ca:Càncer de pròstata da:Prostatakræft de:Prostatakrebs dv:ޕްރޮސްޓޭޓް ކެންސަރު el:Καρκίνος του προστάτη fa:سرطان پروستات hr:Rak prostate id:Kanker prostat it:Carcinoma della prostata he:סרטן הערמונית la:Cancer prostatae lv:Prostatas vēzis nl:Prostaatkanker no:Prostatakreft simple:Prostate cancer fi:Eturauhassyöpä sv:Prostatacancer tl:Kanser sa prostata