Peripheral arterial disease

| Peripheral arterial disease | |

| |

|---|---|

| Peripheral vascular disease of the hand: Advanced disease with gangrene of several digits. (Image courtesy of Charlie Goldberg, M.D.) | |

| ICD-10 | I73.9 |

| ICD-9 | 443.9 |

| DiseasesDB | 31142 |

| eMedicine | med/391 emerg/862 |

| MeSH | D016491 |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Peripheral arterial disease further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Template:WikiDoc Cardiology News Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) also known as peripheral vascular disease (PVD) or peripheral artery occlusive disease (PAOD), is a collator for all diseases caused by the obstruction of large peripheral arteries, which can result from atherosclerosis, inflammatory processes leading to stenosis, an embolism or thrombus formation. It causes either acute or chronic ischemia (lack of blood supply), typically of the legs.

Prevalence and Incidence

The prevalence of peripheral vascular disease in people aged over 55 years is 10%–25% and increases with age; 70%–80% of affected individuals are asymptomatic; only a minority ever require revascularisation or amputation.[1]

In the USA peripheral arterial disease affects 12-20 percent of Americans age 65 and older. Despite its prevalence and cardiovascular risk implications, only 25 percent of PAD patients are undergoing treatment.[2]

The incidence of symptomatic PVD increases with age, from about 0.3% per year for men aged 40–55 years to about 1% per year for men aged over 75 years. The prevalence of PVD varies considerably depending on how PAD is defined, and the age of the population being studied.[1] Diagnosis is critical, as people with PAD have a four to five times higher risk of heart attack or stroke.

In Western Australia, the prevalence of symptomatic disease at around 60 years of age is about 5%.[3]

A study from the NHANES 1999–2000 data found that PVD affects approximately 5 million adults.[2]

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial and U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study trials in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, respectively, demonstrated that glycemic control is more strongly associated with microvascular disease than macrovascular disease. It may be that pathologic changes occurring in small vessels are more sensitive to chronically elevated glucose levels than is atherosclerosis occurring in larger arteries.[4]

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Lower Extremity PAD - Prevalence

- Affects a large proportion of most adult populations worldwide

- Increases with age and with exposure to atherosclerotic risk factors.

- Defined by:

- Claudication as a symptomatic marker

- Abnormal ankle-to brachial systolic blood pressure index (Ankle-Brachial Index or ABI)

- Underlying atherosclerosis risk factor profile

- Presence of other concomitant manifestations of atherosclerosis

Classification

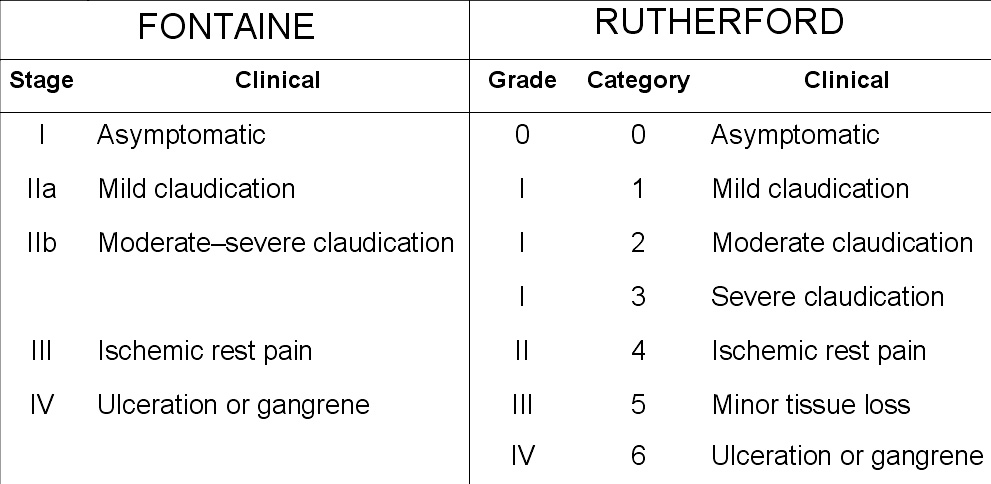

Peripheral artery occlusive disease is commonly divided in the Fontaine stages, introduced by Dr René Fontaine in 1954:[5]

- I: mild pain on walking ("claudication")

- II: severe pain on walking relatively shorter distances (intermittent claudication)

- III: pain while resting

- IV: tissue loss (gangrene)

Risk Factors

Traditional risk factors:

- Advanced age

- Prevalence of PAD increases with age

- PAD may be present in younger individuals (≤ 50 years of age), such patients represent a very small percentage of cases

- Younger patients with PAD tend to have poorer overall long-term outcomes, as well as a higher number of failed bypass surgeries leading to amputation, compared with their older counterparts.

- Cigarette smoking

- The single most modifiable risk factor for the development of PAD and its complications:

- Intermittent claudication

- Critical limb ischemia

- Smoking increases the risk of PAD fourfold and accelerates the onset of PAD symptoms by nearly a decade

- An apparent dose-response relationship exists between the pack-year history and PAD risk

- Compared with their nonsmoking counterparts, smokers with PAD have poorer survival rates and are more likely to progress to critical limb ischemia, and twice as likely to progress to amputation, and also have reduced arterial bypass graft patency rates.

- Individuals who are able to stop smoking are less likely to develop rest pain and have improved survival

- The association between smoking and PAD is about twice as strong as that between smoking and coronary artery disease

- The single most modifiable risk factor for the development of PAD and its complications:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Confers a 1.5-fold to 4-fold increase in the risk of developing symptomatic or asymptomatic PAD and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and early mortality among individuals with PAD.

- In patients with diabetes, the prevalence and extent of PAD also appears to correlate with the age of the individual and the duration and severity of his or her diabetes

- Diabetes is a stronger risk factor for PAD in women than in men

- The prevalence of PAD is higher in African Americans and Hispanics with diabetes than in non-Hispanic whites with diabetes

- Severity of diabetes plays an important role in the development of PAD

- There is a 28% increase of PAD for every percentage-point increase in hemoglobin A1c

- The seriousness of PAD appears to be related to both the duration of hyperglycemia and to glycemic control

- PAD prevalence is also increased in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance

- Diabetes is most strongly associated with the occlusive disease in the tibial arteries

- Patients with PAD and diabetes are more likely to develop microangiography and neuropathy and to have impaired wound healing than those with PAD alone

- PAD tends to present later in life and in a more severe and progressive form in diabetics than nondiabetics, as a result of PAD being more asymptomatic in diabetics

- PAD patients who have diabetes also have a higher risk for ischemic ulceration and gangrene

- Persons with diabetes are more than likely to have additional risk factors as compared to their nondiabetic counterparts:

- Tobacco use

- Elevated blood pressure

- Increased levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, and other blood lipids

- Increased vascular inflammation

- Endothelial cell dysfunction

- Abnormalities in vascular smooth muscle cells

- Diabetes is also associated with increases in platelet aggregation and impaired fibrinolytic function

- Dyslipidemia

- Increases the adjusted likelihood of developing PAD by 10% for every 10-mg/dL rise in total cholesterol

- Elevations in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides are all independent risk factors for PAD

- Elevations in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and apolipoprotein A-I appear to be protective

- The form of dyslipidemia seen most frequently in patients with PAD is the combination of a reduced HDL cholesterol level and an elevated triglyceride level (commonly seen in patients with the metabolic syndrome and diabetes)

- Hypertension

- Hypertension has been reported in as 50-92% of patients with PAD.

- Patients with PAD and hypertension are at greatly increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction independent of other risk factors

Nontraditional risk factors:

- Race/ethnicity

- PAD has been shown to be disproportionately prevalent in black and Hispanic populations

- Elevated levels of inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, leukocytes, interleukin-6)

- Chronic kidney disease

- Association of PAD and chronic kidney disease appears to apply to more severe renal disease

- The prevalence of an abnormal ABI (< 0.90) is much higher in patients with end-stage renal disease than in those with chronic kidney disease, ranging between 30% and 38%

- PAD patients with chronic kidney disease are at increased risk for critical limb ischemia, while those with end-stage renal disease are at increased risk for amputation

- The association between PAD and chronic kidney disease is independent of diabetes, hypertension, ethnicity and age

- May be related to the increased vascular inflammation and markedly elevated plasma homocysteine levels seen in chronic kidney disease

- Genetics

- Genetic predisposition to PAD is supported by observations of increased rates of cardiovascular disease (including PAD) in "healthy" relatives of patients with intermittent claudication

- To date, no major gene for PAD has been detected

- Hypercoaguable states (altered levels of D-dimer, homocysteine, lipoprotein[a])

- Uncommon risk factor for PAD

- In younger persons who lack traditional risk factors, patients with a strong family history of premature atherosclerosis, and individuals in whom arterial revascularization fails for no apparent technical reason, evaluation of hypercoaguable condition should be considered

- Evaluation of elevated homocysteine and lipoprotein(a) levels appears to be important in individuals with diffuse PAD who lack traditional risk factors

- Hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with premature atherosclerosis and appears to be a stronger risk factor for PAD than for CAD.

- Also been implicated in PAD progression and as a risk factor for failure of peripheral arterial interventions

- Abnormal waist-to-hip ratio

- An association between abdominal obesity and PAD has been reported, although it is unclear whether any association exists between PAD and body mass index (BMI)

- The lack of association between PAD and BMI can be explained by the tendency of smokers (those at an increased risk for PAD) have lower BMIs than nonsmokers. Also, many of the individuals at risk for PAD are elderly males, who generally have lower BMIs as well.

Pathophysiology & Etiology

- Atherosclerosis

- Degenerative diseases: Marfan's Syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Neurofibromatosis, arteriomegaly

- Dysplastic disorders: Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Vascular inflamation : Takayasu's Arteritis

- In situ thrombosis

- Thromboembolism

- PAD is a manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis that has developed over many years.

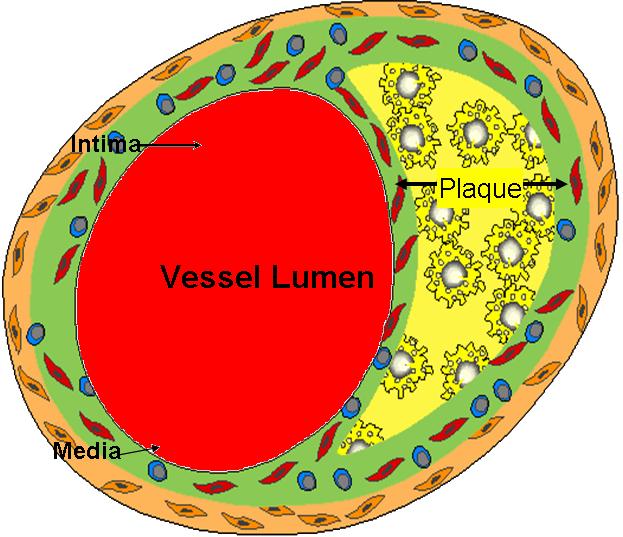

- Atherosclerosis is a complex process that involves endothelial dysfunction, lipid disturbances, platelet activation, thrombosis, oxidative stress, vascular smooth muscle activation, altered matrix metabolism, remodeling and genetic factors

- Atherosclerosis frequently develops at arterial bifurcations and branches where endogenous atheroprotective mechanisms are impaired as a result of the effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells

- The stages of atherosclerosis are divided into the following:

- Lesion initiation

- Results from endothelial dysfunction

- Formation of the fatty streak

- Results from an inflammatory lesion that develops first

- Affects the intima of the artery and leads to formation of the foam cell

- Fatty streak consists primarily of smooth muscle cells, monocytes, macrophages, and T and B cells

- Fibroproliferative atheroma development

- Originates from the fatty streak

- Contains larger numbers of smooth muscle cells frlled with lipids

- Advanced lesion development

- Results from continued accumulation of cells that make up the fatty streak and fibroproliferative atheroma

- Highly cellular

- Contains intrinsic vascular cell walls (both endothelial and smooth muscle), and inflammatory cells (monocytes, macrophages, and T lymphocytes)

- Also contains a lipid core covered by a fibrous cap

- Lesion initiation

- Arteries initially compensate for atherosclerosis by remodeling, which causes the blood vessels to increase in size

- Advanced lesions eventually intrude into the lumen, resultsing in flow-limiting stenoses and chronic ischemic syndromes

- Acute arterial events occur if the fibrous cap is disrupted, the resulting exposure of the "prothrombotic" necrotic lipid core and subendothelial tissue leads to thrombus formation and flow occlusion

- In addition to coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease, PAD is one of the three major syndromes of atherothrombosis

- Atherothrombosis is the term currently used to describe the process of thrombus formation on top of a ruptured plaque located at a disease arterial segment

- Such atherosclerotic plaques tend to occur at vessel bifurcations, presumed to be due to both impaired atheroprotective mechanisms and disturbed blood flow leading to local intimal injury

- Panvascular disease refers to clinically significant atherosclerosis is present in multiple vascular beds

Natural History

- An accurate history is the key to the diagnosis of PAD

- Eliciting atherosclerotic risk factors in the history may help to identify patients, who although asymptomatic, have evidence of PAD on physical examination or noninvasive testing.

Diagnosis

Clinical Diagnosis

- Must have a high index of suspicion

- Must perform a thorough physicial examination

- Determine the global atherosclerotic burden

- Utilize the vascular diagnostic laboratory

- Magnetic resonance angiography is rapidly replacing invasive testing

- Reserve arteriography for cases requiring intervention

-

Diagram of arterial lumen (Image courtesy of Amjad Almahameed)

-

Peripheral Vascular Disease of the Hand: Advanced disease with gangrene of several digits.

(Image courtesy of Charlie Goldberg, M.D.)

Differential Diagnosis

- Intermittent claudication (IC) must be differentiated from lower extremity pain with nonvascular etiologies

- Many concomitant disease processes can complicate the diagnosis of PAD

- Both neurologic and musculoskeletal and venous pathology can cause leg pain or coexist with leg pain from PAD

- False-positive diagnosis rates of up to 44% and false-negative rates of up to 19% have been reported

- Calf claudication is commonly confused with pain from venous disease, nerve root compression or spinal cord stenosis

- Hip and buttock claudication is commonly confused with osteoarthritis of the hip or with spinal canal narrowing due to osteoarthritis

- Nonatherosclerotic conditions that mimic intermittent claudication:

- Venous Claudication

- Occurs in patients with chronic venous insufficiency and those who develop post-thrombotic syndrome after deep venous thrombosis

- Baseline venous hypertension in the obstructed veins worsens with exercise and produces a tight bursting pressure in the limb, usually worse in the thigh and uncommonly in the calf

- Usually associated with evidence of venous edema in the leg

- Venous claudication tends to improve with cessation of exercise, but total resolution takes much longer than resolution of intermittent claudication (IC), and may require leg elevation

- Chronic compartment syndrome

- An uncommon cause of exercise-induced leg pain

- Tends to occur in young athletes, who develop increased pressure within a fixed compartment, compromising perfusion and function of the tissues within that space

- Results from thickened fascia, muscular hypertrophy or when external pressure is applied to the leg

- Presentation is one of tight bursting pressure in the calf or foot following participation in endurance sports or other robust exercise

- Pain subsides slowly with rest

- Intracompartmental pressure testing before and after exercise is the diagnostic test of choice

- Peripheral nerve pain

- Generally attributable to nerve root compression by herniated disks or osteophytes and typically follows the dermatome of the affected root

- Pain usually begins immediately upon walking and may be felt in the calf or lower leg

- Pain is not quickly relieved by rest and may even be present at rest

- A sensation of pain running down the back of the leg as well as a history of back problems may be present

- Spinal chord compression from narrowing secondary to lumbar spine osteoarthritis

- In patients with cauda equina syndrome, upright positioning aggravates the narrowing of the spinal canal, therefore causing symptoms.

- Upright standing may produce pain, weakness or discomfort in the hips, thighs and buttocks, and sometimes a sensation of numbness and paresthesias, although symptoms are usually associated with walking.

- Symptoms are alleviated by sitting or flexing the lumbar spine forward as opposed to standing, which alleviates pain caused by IC.

- Hip and knee osteoarthritis

- Osteoarthritis in joints is typically worse in the morning or at the initiation of movement

- Degree of pain varies day to day, does not cease upon stopping exercise or standing

- Pain improves after sitting, lying down, or leaning against an object to alleviate weight-bearing on the joint.

- Pain may be affected by weather changes, and may be present at rest

- Nonatherosclerotic etiologies of arterial disease:

- Thromboangiitis obliterans

- Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome

- Cystic adventitial disease

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Exercise-induced endofibrosis of the iliac arteries

- Other arterial causes of IC or critical limb ischemia

- All of these conditions generally produce a decrease in the exercise or resting ABI

- Usually differentiated from atherosclerotic etiologies by the history and physical examination

- Venous Claudication

History and Symptoms

- Signs of PAD

- Decreased or absent pulses

- Bruits

- Muscle atrophy

- Pallor of feet with elevation

- Dependent rubor

- Signs of chronic ischemia:

- Hair loss, thickened nails, smooth & shiny skin, coolness, pallor or cyanosis

- Individuals at risk for Lower-extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease

- Age less than 50 years, with diabetes and one other atherosclerosis risk factor (smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, or hyperhomocysteinemia)

- Age 50 to 69 years and history of smoking or diabetes

- Age 70 years and older

- Leg symptoms with exertion (suggestive of claudication or ischemic rest pain

- Abnormal lower extremity pulse examination

- Known atherosclerotic coronary, carotid, or renal artery disease

- PAD symptoms severity

- Maximal walking speed

- Normal = 3-4 mph

- PAD = 1-2 mph

- Maximal walking distance

- Normal = unlimited

- PAD, 31% difficulty walking in home

- PAD, 66% difficulty walking 1/2 block

- Peak VO2

- PAD reduced 50% (NYHA class III CHF)

- Maximal walking speed

Vascular Review of Systems

Any exertional limitation of the lower extremity muscles or any history of walking impairment (fatigue, numbness, aching, or pain Any poorly healing or non healing of the legs or feet Any pain at rest localized at the lower leg or foot and its association with the upright or recumbent positions Postprandial abdominal pain that reproducibly is provoked by eating and is associated with weight loss Family history of a first-degree relative with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Physical Examination

Vascular Physical Examination

- Measurement of blood pressure in both arm and notation of any interarm assymetry

- Palpation of the carotid pulses and notation of the carotid upstroke and amplitude and presence of bruits

- Auscultation of the abdomen and flank for bruits

- Palpation of the pulses at the brachial, radial ulnar, femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial sites. Performance of Allen’s test when knowledge of hand perfusion is needed

- Auscultation of both femoral ateries for the presence of bruits

- Pulse intensity should be recorded numerically: 0, absent; 1, diminished; 2, normal; 3, bounding

- Additional findings: distal hair loss, trophic sin changes hypertrophic nails

Laboratory Findings

Typical Noninvasive Vascular Laboratory Tests for Lower Extremity PAD Patients by Clinical Presentation - ACC/AHA Guidelines

Clinical presentation Noninvasive vascular test Asymptomatic lower extremity PAD ABI Claudication ABI, PVR, or segmental pressures; Duplex ultrasound; Exercise test with ABI or assess functional status Possible pseudoclaudication Exercise test with ABI Postoperative vein graft follow-up Duplex ultrasound Femoral pseudoaneurysm, iliac or popliteal aneurysm Duplex ultrasound Suspected aortic aneurysm; serial AAA follow-up Abdominal ultrasound, CTA, or MRA Candidate for revascularization Duplex ultrasound, MRA, or CTA

MRI and CT

- Computed tomographic angiography

- Benefits

- Useful to asses PAD anatomy and presence of significant stenoses

- Useful to select patients who are candidates for endovascular or surgical revascularization

- Helpful to provide associated soft tissue diagnostic information that may be associated with PAD presentation

- Metal clips, stents, and metallic prostheses do not cause significant CTA artifacts

- Scan times are significantly faster than for MRA

- Limitations

- Single-detector computed tomography lacks accuracy for detection of stenosis

- Spatial resolution lower than digital subtraction angiography

- Accuracy and effectiveness not as well determined as MRA

- Asymmetrical opacification in legs may obscure arterial phase in some vessels

- Requires iodinated contrast and ionizing radiation

- Venous opacification can obscure arterial filling

- Benefits

- Magnetic resonance angiography

- Benefits

- Useful to asses PAD anatomy and presence of significant stenoses

- Useful to select patients who are candidates for endovascular or surgical revascularization

- Limitations

- Tends to overestimate the degree of stenosis

- May be inaccurate in arteries treated with metal stents

- Can not be used in patients with contraindications to the magnetic resonance technique

- Benefits

- Contrast angiography

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

- Duplex ultrasound

- Benefits

- Can establish the lower extremity PAD diagnosis, establish localization, and define severity of local lower extremity arterial stenoses

- Can be useful to select candidates for endovascular or surgical revascularization

- Limitations

- Accuracy is diminished in proximal aortoiliac arterial segments in some individuals

- Dense arterial calcification can limit diagnostic accuracy

- Sensitivity is diminished for detection of stenoses downstream from a proximal stenosis

- Diminished predictive value in surveillance or prosthetic bypass grafts

- Benefits

Other Diagnostic Studies

- Ankle-Brachial Index, segmental pressure examination

- Pulse volume recording

- Continuous wave doppler ultrasound

- Treadmill exercise testing with and without ABI assessments and 6 minute walk test

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

- The diagnosis of PAD places a patient at high risk of major cardiovascular events, specifically myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and death.

- Patients with PAD have a twofold to fourfold increase in the risk of all-cause mortality and a threefold to sixfold increase in the risk of cardiovascular death relative to patients without PAD

- Patients with PAD also have a higher risk of an MI or a stroke than of a limb-related event, such as:

- Lower extremity ulcer

- Gangrene

- Need for amputation

- The risk of a major cardiovascular event is highest among patients with the most severe PAD, such as those with critical limb ischemia, in whom 1-year event rates are as high as 20% to 25%

- All patients with PAD should be targeted with the same secondary prevention goals as patients with coronary artery disease.

- Peripheral arterial disease is a true coronary risk equivalent

Endovascular Treatment Interpreting Outcomes

- Changing technology: PTA vs stent

- Evolving medical therapy

- Case series

- Heterogenous lesions: stenosis vs occlusion

- Heterogenous population: symptom status

- Outcome measures:

- Hemodynamic versus clinical patency

- CFA flow pattern

- Ankle-Brachial Index

- Thigh/brachial index

- Absence of symptoms

- Improvement of symptoms

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

FDA Approved Drugs:

- Pentoxifylline

- Cilostazol

- Side effects:

- Headache

- Diarrhea

- Gastric upset

- Palpitations

- Dizziness

- Side effects:

Drugs Under Investigation:

- Atorvastatin

- Rosiglitazone

- Propionyl- L-Carnitine

- L-Arginine

- Prostaglandins

- Angiogenic Factors: VEGF,bFGF

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

- Antiplatelet therapy is indicated for all patients with PAD unless contraindicated for a compelling reason

- Aspirin is recommended, which reduces vascular events and appears to prevent peripheral arterial occlusion after revascularization procedures

Surgery and Device Based Therapy

Indications for Surgery

- Automatic indications

- Gangrene

- Non-healing ulcers

- Ischemic rest pain

- Claudication causing lifestyle deterioration, refractory to pharmacologic intervention and behavioral modification

Guidelines

Several different guideline standards have been developed, including:

- ACC/AHA Guidelines[9]

Associations

Many PVD patients also have angina pectoris or have had myocardial infarction. There is also an increased risk for stroke.

The moderate consumption of alcohol has been found to be associated with a reduction of the risk of PVD by almost one-third compared to those who do not drink alcohol.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Peripheral arterial disease prevention and prevalence". Peripheral Arterial Disease. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Unknown parameter

|publsiher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 A. Richey Sharrett, MD, DRPH (2007). "Peripheral arterial disease prevalence". Peripheral Arterial Disease. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Unknown parameter

|publsiher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hiatt W, Hoag S, Hamman R. (1995). "Effect of diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of peripheral arterial disease". Effect of diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of peripheral arterial disease. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Unknown parameter

|publsiher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Elizabeth Selvin, PHD, MPH, Keattiyoat Wattanakit, MD, MPH, Michael W. Steffes, MD, PHD, Josef Coresh, MD, PHD and A. Richey Sharrett, MD, DRPH (2005). "HbA1c and Peripheral Arterial Disease in Diabetes". The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Unknown parameter

|publsiher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Fontaine R, Kim M, Kieny R (1954). "Die chirugische Behandlung der peripheren Durchblutungsstörungen. (Surgical treatment of peripheral circulation disorders)". Helvetica Chirurgica Acta (in German). 21 (5/6): 499&ndash, 533. PMID 14366554.

- ↑ Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG; TASC II Working Group, Bell K, Caporusso J, Durand-Zaleski I, Komori K, Lammer J, Liapis C, Novo S, Razavi M, Robbs J, Schaper N, Shigematsu H, Sapoval M, White C, White J; TASC II Working Group. (2007). "Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II)". Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 33 (Suppl 1): S1–75. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.09.024. PMID 17140820.

- ↑ Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG; TASC II Working Group, Bell K, Caporusso J, Durand-Zaleski I, Komori K, Lammer J, Liapis C, Novo S, Razavi M, Robbs J, Schaper N, Shigematsu H, Sapoval M, White C, White J; TASC II Working Group. (2007). "Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II)". J Vasc Surg. 45 (Suppl S): S5–67. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. PMID 17223489.

- ↑ Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG; TASC II Working Group, Bell K, Caporusso J, Durand-Zaleski I, Komori K, Lammer J, Liapis C, Novo S, Razavi M, Robbs J, Schaper N, Shigematsu H, Sapoval M, White C, White J; TASC II Working Group. (2007). "Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease". Int Angiol. 26 (2): 81–157. PMID 17489079.

- ↑ Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR; et al. (2006). "ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47 (6): 1239–312. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.009. PMID 16545667.

- ↑ Camargo CA, Stampfer MJ, Glynn RJ; et al. (1997). "Prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of peripheral arterial disease in US male physicians". Circulation. 95 (3): 577–80. PMID 9024142. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)

Subclavian Artery Disease Renovascular Disease Aortoiliac Disease